Chiral symmetry

In quantum field theory, chiral symmetry is a possible symmetry of the Lagrangian under which the left-handed and right-handed parts of Dirac fields transform independently.

The chiral symmetry transformation can be divided into a component that treats the left-handed and the right-handed parts equally, known as vector symmetry, and a component that actually treats them differently, known as axial symmetry.[1] A scalar field model encoding chiral symmetry and its breaking is the sigma model.

Example: u and d quarks in QCD

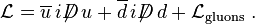

Consider quantum chromodynamics (QCD) with two massless quarks u and d (massive fermions do not exhibit chiral symmetry). The Lagrangian reads

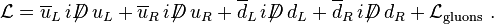

In terms of left-handed and right-handed spinors, it reads

(Here, i is the imaginary unit and  the Dirac operator.)

the Dirac operator.)

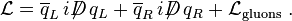

Defining

it can be written as

The Lagrangian is unchanged under a rotation of qL by any 2 x 2 unitary matrix L, and qR by any 2 x 2 unitary matrix R.

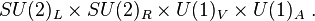

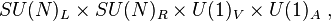

This symmetry of the Lagrangian is called flavor chiral symmetry, and denoted as U(2)L×U(2)R. It decomposes into

The singlet vector symmetry, U(1)V, acts as

and corresponds to baryon number conservation.

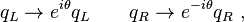

The singlet axial group U(1)A acts as

and it does not correspond to a conserved quantity, because it is explicitly violated due to a quantum anomaly.

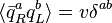

The remaining chiral symmetry SU(2)L×SU(2)R turns out to be spontaneously broken by a quark condensate

formed through nonperturbative action of QCD gluons,

into the diagonal vector subgroup SU(2)V known as isospin. The Goldstone bosons corresponding to the three broken generators are the three pions.

As a consequence, the effective theory of QCD bound states like the baryons, must now include mass terms for them, ostensibly disallowed by unbroken chiral symmetry. Thus, this chiral symmetry breaking induces the bulk of hadron masses, such as those for the nucleons−−in effect, the bulk of the mass of all visible matter.

formed through nonperturbative action of QCD gluons,

into the diagonal vector subgroup SU(2)V known as isospin. The Goldstone bosons corresponding to the three broken generators are the three pions.

As a consequence, the effective theory of QCD bound states like the baryons, must now include mass terms for them, ostensibly disallowed by unbroken chiral symmetry. Thus, this chiral symmetry breaking induces the bulk of hadron masses, such as those for the nucleons−−in effect, the bulk of the mass of all visible matter.

In the real world, because of the nonvanishing and differing masses of the quarks, SU(2)L×SU(2)R is only an approximate symmetry[2] to begin with, and therefore the pions are not massless, but have small masses: they are pseudo-Goldstone bosons.[3]

More Flavors

For more "light" quark species, N flavors in general, the corresponding chiral symmetries are U(N)L×U(N)R, decomposing into

and exhibiting a very analogous chiral symmetry breaking pattern.

Most usually, N=3 is taken, the u, d, and s quarks taken to be light (the Eightfold way (physics)), so then approximately massless for the symmetry to be meaningful to a lowest order, while the other three quarks are sufficiently heavy to barely have a residual chiral symmetry be visible for practical purposes.

References

- ↑ Ta-Pei Cheng and Ling-Fong Li, Gauge Theory of Elementary Particle Physics, (Oxford 1984) ISBN 978-0198519614

- ↑ Gell-Mann, M.; Renner, B. (1968). "Behavior of Current Divergences under SU_{3}×SU_{3}". Physical Review 175 (5): 2195. Bibcode:1968PhRv..175.2195G. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.175.2195.

- ↑ Peskin, Michael; Schroeder, Daniel (1995). An Introduction to Quantum Field Theory. Westview Press. p. 670. ISBN 0-201-50397-2.