Chinese mathematics

Mathematics in China emerged independently by the 11th century BC.[1] The Chinese independently developed very large and negative numbers, decimals, a place value decimal system, a binary system, algebra, geometry, and trigonometry. Knowledge of Chinese mathematics before 254 BC is somewhat fragmentary, and even after this date the manuscript traditions are obscure. Dates centuries before the classical period are generally considered conjectural by Chinese scholars unless accompanied by verified archaeological evidence, in a direct analogue with the situation in the Far West. Neither Western nor Chinese archaeological findings comparable to those for Babylonia or Egypt are known.

As in other early societies the focus was on astronomy in order to perfect the agricultural calendar, and other practical tasks, and not on establishing formal systems. Ancient Chinese mathematicians did not develop an axiomatic approach, but made advances in algorithm development and algebra. While the Greek mathematics declined in the west during the mediaeval times, the achievement of Chinese algebra reached its zenith in the 13th century, when Zhu Shijie invented the method of four unknowns.

As a result of obvious linguistic and geographic barriers, as well as content, Chinese mathematics and that of the mathematics of the ancient Mediterranean world are presumed to have developed more or less independently up to the time when The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art reached its final form, while the Writings on Reckoning and Huainanzi are roughly contemporary with classical Greek mathematics. Some exchange of ideas across Asia through known cultural exchanges from at least Roman times is likely. Frequently, elements of the mathematics of early societies correspond to rudimentary results found later in branches of modern mathematics such as geometry or number theory. The Pythagorean theorem for example, has been attested to the time of the Duke of Zhou. Knowledge of Pascal's triangle has also been shown to have existed in China centuries before Pascal,[2] such as by Shen Kuo.

Early Chinese mathematics

Simple mathematics on Oracle bone script date back to the Shang Dynasty (1600–1050 BC). One of the oldest surviving mathematical works is the Yi Jing, which greatly influenced written literature during the Zhou Dynasty (1050–256 BC). For mathematics, the book included a sophisticated use of hexagrams. Leibniz pointed out, the I Ching contained elements of binary numbers.

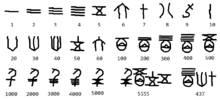

Since the Shang period, the Chinese had already fully developed a decimal system. Since early times, Chinese understood basic arithmetic (which dominated far eastern history), algebra, equations, and negative numbers with counting rods. Although the Chinese were more focused on arithmetic and advanced algebra for astronomical uses, they were also the first to develop negative numbers, algebraic geometry (only Chinese geometry) and the usage of decimals.

Math was one of the Liù Yì (六艺) or Six Arts, students were required to master during the Zhou Dynasty (1122–256 BC). Learning them all perfectly was required to be a perfect gentleman, or in the Chinese sense, a "Renaissance Man". Six Arts have their roots in the Confucian philosophy.

The oldest existent work on geometry in China comes from the philosophical Mohist canon of c. 330 BC, compiled by the followers of Mozi (470–390 BC). The Mo Jing described various aspects of many fields associated with physical science, and provided a small wealth of information on mathematics as well. It provided an 'atomic' definition of the geometric point, stating that a line is separated into parts, and the part which has no remaining parts (i.e. cannot be divided into smaller parts) and thus forms the extreme end of a line is a point.[3] Much like Euclid's first and third definitions and Plato's 'beginning of a line', the Mo Jing stated that "a point may stand at the end (of a line) or at its beginning like a head-presentation in childbirth. (As to its invisibility) there is nothing similar to it."[4] Similar to the atomists of Democritus, the Mo Jing stated that a point is the smallest unit, and cannot be cut in half, since 'nothing' cannot be halved.[4] It stated that two lines of equal length will always finish at the same place,[4] while providing definitions for the comparison of lengths and for parallels,[5] along with principles of space and bounded space.[6] It also described the fact that planes without the quality of thickness cannot be piled up since they cannot mutually touch.[7] The book provided word recognition for circumference, diameter, and radius, along with the definition of volume.[8]

The history of mathematical development lacks some evidence. There are still debates about certain mathematical classics. For example, the Zhou Bi Suan Jing dates around 1200–1000 BC, yet many scholars believed it was written between 300–250 BC. The Zhou Bi Suan Jing contains an in-depth proof of the Gougu Theorem (a special case of the Pythagorean Theorem) but focuses more on astronomical calculations.

The abacus was first mentioned in the second century BC, alongside 'calculation with rods' (suan zi) in which small bamboo sticks are placed in successive squares of a checkerboard.[9]

Qin mathematics

Not much is known about Qin dynasty mathematics, or before, due to the burning of books and burying of scholars, circa 213–210 BCE.

Knowledge of this period must be carefully determined by their civil projects and historical evidence. The Qin dynasty created a standard system of weights. Civil projects of the Qin dynasty were incredible feats of human engineering. Emperor Qin Shihuang(秦始皇)ordered many men to build large, lifesize statues for the palace tomb along with various other temples and shrines. The shape of the tomb is designed with geometric skills of architecture. It is certain that one of the greatest feats of human history; the great wall required many mathematical "techniques." All Qin dynasty buildings and grand projects used advanced computation formulas for volume, area and proportion.

Qin bamboo cash purchased at the antiquarian market of Hong Kong by the Yuelu Academy, according to the preliminary reports, contains the earliest epigraphic sample of a mathematical treatise.

Han mathematics

In the Han Dynasty, numbers were developed into a place value decimal system and used on a counting board with a set of counting rods called chousuan,consisted of only nine symbols, a blank space on the counting board stood for zero. The mathematicians Liu Xin (d. 23) and Zhang Heng (78–139) gave more accurate approximations for pi than Chinese of previous centuries had used. Zhang also applied mathematics in his work in astronomy. Hundreds of examples of the practical use of mathematics by Qin and Han administrators have been excavated, proving that many of the topics discussed in theoretical treatises were actually in use.[10]

Suan shu shu

The Suàn shù shū (writings on reckoning) is an ancient Chinese text on mathematics approximately seven thousand characters in length, written on 190 bamboo strips. It was discovered together with other writings in 1984 when archaeologists opened a tomb at Zhangjiashan in Hubei province. From documentary evidence this tomb is known to have been closed in 186 BC, early in the Western Han dynasty. While its relationship to the Nine Chapters is still under discussion by scholars, some of its contents are clearly paralleled there. The text of the Suan shu shu is however much less systematic than the Nine Chapters, and appears to consist of a number of more or less independent short sections of text drawn from a number of sources. Some linguistic hints point back to the Qin dynasty.

In an example of an elementary mathematics in the Suàn shù shū, the square root is approximated by using an "excess and deficiency" method which says to "combine the excess and deficiency as the divisor; (taking) the deficiency numerator multiplied by the excess denominator and the excess numerator times the deficiency denominator, combine them as the dividend."[11]

The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art

The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art is a Chinese mathematics book, its oldest archeological date being 179 AD (traditionally dated 1000 BC), but perhaps as early as 300–200 BC. Although the author(s) are unknown, they made a huge contribution in the eastern world. The methods were made for everyday life and gradually taught advanced methods. It also contains evidence of the Gaussian elimination and Cramer's Rule for system of linear equations.

It was one of the most influential of all Chinese mathematical books and it is composed of some 246 problems. Chapter eight deals with solving determinate and indeterminate simultaneous linear equations using positive and negative numbers, with one problem dealing with solving four equations in five unknowns.[12] Estimates concerning the Chou Pei Suan Ching, generally considered to be the oldest of the mathematical classics, differ by almost a thousand years. A date of about 300 BC would appear reasonable, thus placing it in close competition with another treatise, the Jiu zhang suanshu, composed about 250 BC, that is, shortly before the Han dynasty (202 BC). Almost as old at the Chou Pei, and perhaps the most influential of all Chinese mathematical books, was the Jiuzhang suanshu, or Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art. This book includes 246 problems on surveying, agriculture, partnerships, engineering, taxation, calculation, the solution of equations, and the properties of right triangles. Chapter eight of the Nine chapters is significant for its solution of problems of simultaneous linear equations, using both positive and negative numbers. The earliest known magic squares appeared in China.[13] The Chinese were especially fond of patterns, as a natural outcome of arranging counting rods in rows on counting board to carry out computation; hence,it is not surprising that the first record (of ancient but unknown origin) of a magic square appeared there. The concern for such patterns led the author of the Nine Chapters to solve the system of simultaneous linear equations by placing the coefficients and constant terms of the linear equations into a matrix and performing column reducing operations on the matrix to reduce it to a triangular form represented by the equations 36z = 99, 5y + z = 24, and 3x + 2y + z = 39 from which the values of z, y, and x are successively found with ease. The last problem in the chapter involves four equations in five unknowns, and the topic of indeterminate equations was to remain a favorite among Oriental peoples.

Mathematics in the period of disunity

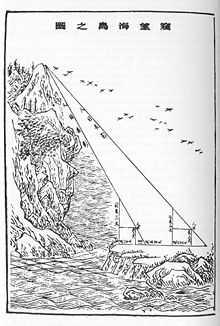

In the third century Liu Hui wrote his commentary on the Nine Chapters and also wrote Haidao suanjing which dealt with using Pythagorean theorem (already known by the 9 chapters), and triple, quadruple triangulation for surveying; his accomplishment in the mathematical surveying exceeded those accomplished in the west by a millennium.[14] He was the first Chinese mathematician to calculate π=3.1416 with his π algorithm. He discovered the usage of Cavalieri's principle to find an accurate formula for the volume of a cylinder, and also developed elements of the integral and the differential calculus during the 3rd century CE.

In the fourth century, another influential mathematician named Zu Chongzhi, introduced the Da Ming Li. This calendar was specifically calculated to predict many cosmological cycles that will occur in a period of time. Very little is really known about his life. Today, the only sources are found in Book of Sui, we now know that Zu Chongzhi was one of the generations of mathematicians. He used Liu Hui's pi-algorithm applied to a 12288-gon and obtained a value of pi to 7 accurate decimal places (between 3.1415926 and 3.1415927), which would remain the most accurate approximation of π available for the next 900 years. He also used He Chengtian's interpolation method for approximating irrational number with fraction in his astronomy and mathematical works, he obtained as a good fraction approximate for pi; Yoshio Mikami commented that neither the Greeks, nor the Hindus nor Arabs knew about this fraction approximation to pi, not until the Dutch mathematician Adrian Anthoniszoom rediscovered it in 1585, "the Chinese had therefore been possessed of this the most extraordinary of all fractional values over a whole millennium earlier than Europe"[15] Along with his son, Zu Geng, Zu Chongzhi used the Cavalieri Method to find an accurate solution for calculating the volume of the sphere. His work, Zhui Shu was discarded out of the syllabus of mathematics during the Song dynasty and lost. Many believed that Zhui Shu contains the formulas and methods for linear, matrix algebra, algorithm for calculating the value of π, formula for the volume of the sphere. The text should also associate with his astronomical methods of interpolation, which would contain knowledge, similar to our modern mathematics.

as a good fraction approximate for pi; Yoshio Mikami commented that neither the Greeks, nor the Hindus nor Arabs knew about this fraction approximation to pi, not until the Dutch mathematician Adrian Anthoniszoom rediscovered it in 1585, "the Chinese had therefore been possessed of this the most extraordinary of all fractional values over a whole millennium earlier than Europe"[15] Along with his son, Zu Geng, Zu Chongzhi used the Cavalieri Method to find an accurate solution for calculating the volume of the sphere. His work, Zhui Shu was discarded out of the syllabus of mathematics during the Song dynasty and lost. Many believed that Zhui Shu contains the formulas and methods for linear, matrix algebra, algorithm for calculating the value of π, formula for the volume of the sphere. The text should also associate with his astronomical methods of interpolation, which would contain knowledge, similar to our modern mathematics.

A mathematical manual called "Sunzi mathematical classic" dated around 400 CE contained the most detailed step by step description of multiplication and division algorithm with counting rods. The earliest record of multiplication and division algorithm using Hindu Arabic numerals was in writing by Al Khwarizmi in the early 9th century. Khwarizmi's step by step division algorithm was completely identical to Sunzi division algorithm described in Sunzi mathematical classic four centuries earlier.[16] Khwarizmi's work was translated into Latin in the 13th century and spread to the west, the division algorithm later evolved into Galley division. The route of transmission of Chinese place value decimal arithmetic know how to the west is unclear, how Sunzi's division and multiplication algorithm with rod calculus ended up in Hindu Arabic numeral form in Khwarizmi's work is unclear, as al Khwarizmi never given any Sankrit source nor quoted any Sanskrit stanza. However, the influence of rod calculus on Hindu division is evident, for example in the division example, 324 should be 32400, only rod calculus used blanks for zeros.[17]

In the fifth century the manual called "Zhang Qiujian suanjing" discussed linear and quadratic equations. By this point the Chinese had the concept of negative numbers.

Tang mathematics

By the Tang Dynasty study of mathematics was fairly standard in the great schools. The Ten Computational Canons was a collection of ten Chinese mathematical works, compiled by early Tang dynasty mathematician Li Chunfeng (李淳风 602-670),as the official mathematical texts for imperial examinations in mathematics.

Wang Xiaotong was a great mathematician in the beginning of the Tang Dynasty, and he wrote a book: Jigu Suanjing (Continuation of Ancient Mathematics), in which cubic equations appear for the first time[18]

The Tibetans obtained their first knowledge of mathematics (arithmetic) from China during the reign of Nam-ri srong btsan, who died in 630.[19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28]

The table of sines by the Indian mathematician, Aryabhata, were translated into the Chinese mathematical book of the Kaiyuan Zhanjing, compiled in 718 AD during the Tang Dynasty.[29] Although the Chinese excelled in other fields of mathematics such as solid geometry, binomial theorem, and complex algebraic formulas,early forms of trigonometry were not as widely appreciated as in the contemporary Indian and Islamic mathematics.[30] I-Xing, the mathematician and Buddhist monk was credited for calculating the tangent table. Instead, the early Chinese used an empirical substitute known as chong cha, while practical use of plane trigonometry in using the sine, the tangent, and the secant were known.[29]

Song and Yuan mathematics

Northern Song Dynasty mathematician Jia Xian developed an additive multiplicative method for extraction of square root and cubic root which implemented the "Horner" rule.[31]

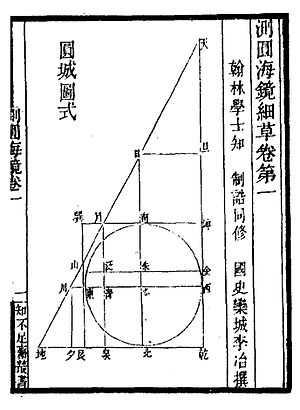

Four outstanding mathematicians arose during the Song Dynasty and Yuan Dynasty, particularly in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries: Yang Hui, Qin Jiushao, Li Zhi (Li Ye), and Zhu Shijie. Yang Hui, Qin Jiushao, Zhu Shijie all used the Horner-Ruffini method six hundred years earlier to solve certain types of simultaneous equations, roots, quadratic, cubic, and quartic equations. Yang Hui was also the first person in history to discover and prove "Pascal's Triangle", along with its binomial proof (although the earliest mention of the Pascal's triangle in China exists before the eleventh century AD). Li Zhi on the other hand, investigated on a form of algebraic geometry based on Tian yuan shu. His book; Ceyuan haijing revolutionized the idea of inscribing a circle into triangles, by turning this geometry problem by algebra instead of the traditional method of using Pythagorean theorem. Guo Shoujing of this era also worked on spherical trigonometry for precise astronomical calculations. At this point of mathematical history, a lot of modern western mathematics were already discovered by Chinese mathematicians. Things grew quiet for a time until the thirteenth century Renaissance of Chinese math. This saw Chinese mathematicians solving equations with methods Europe would not know until the eighteenth century. The high point of this era came with Zhu Shijie's two books Suanxue qimeng and the Siyuan yujian. In one case he reportedly gave a method equivalent to Gauss's pivotal condensation.

Qin Jiushao (c. 1202–1261) was the first to introduce the zero symbol into Chinese mathematics.[32] Before this innovation, blank spaces were used instead of zeros in the system of counting rods.[33] One of the most important contribution of Qan Jiushao was his method of solving high order numerical equations. Referring to Qin's solution of a 4th order equation, Yoshio Mikami put it: "Who can deny the fact of Horner's illustrious process being used in China at least nearly six long centuries earlier than in Europe?"[34] Qin also solved a 10th order equation.[35]

Pascal's triangle was first illustrated in China by Yang Hui in his book Xiangjie Jiuzhang Suanfa (详解九章算法), although it was described earlier around 1100 by Jia Xian.[36] Although the Introduction to Computational Studies (算学启蒙) written by Zhu Shijie (fl. 13th century) in 1299 contained nothing new in Chinese algebra, it had a great impact on the development of Japanese mathematics.[37]

Algebra

Ceyuan haijing

Ceyuan haijing (pinyin: Cèyuán Hǎijìng) (Chinese characters:測圓海鏡), or Sea-Mirror of the Circle Measurements, is a collection of 692 formula and 170 problems related to inscribed circle in a triangle, written by Li Zhi (or Li Ye) (1192–1272 AD). He used Tian yuan shu to convert intricated geometry problems into pure algebra problems. He then used fan fa, or Horner's method, to solve equations of degree as high as six, although he did not describe his method of solving equations.[38] "Li Chih (or Li Yeh, 1192–1279), a mathematician of Peking who was offered a government post by Khublai Khan in 1206, but politely found an excuse to decline it. His Ts'e-yuan hai-ching (Sea-Mirror of the Circle Measurements) includes 170 problems dealing with[...]some of the problems leading to polynomial equations of sixth degree. Although he did not describe his method of solution of equations, it appears that it was not very different from that used by Chu Shih-chieh and Horner. Others who used the Horner method were Ch'in Chiu-shao (ca. 1202 – ca.1261) and Yang Hui (fl. ca. 1261–1275).

Jade Mirror of the Four Unknowns

Si-yüan yü-jian (《四元玉鑒》), or Jade Mirror of the Four Unknowns, was written by Zhu Shijie in 1303 AD and it marks the peak in the development of Chinese algebra. The four elements, called heaven, earth, man and matter, represented the four unknown quantities in his algebraic equations. The Ssy-yüan yü-chien deals with simultaneous equations and with equations of degrees as high as fourteen. The author uses the method of fan fa, today called Horner's method, to solve these equations.(Boyer 1991, "China and India" p. 203) "The last and greatest of the Sung mathematicians was Chu Chih-chieh (fl. 1280–1303), yet we known little about him-, [...]Of greater historical and mathematical interest is the Ssy-yüan yü-chien(Precious Mirror of the Four Elements) of 1303. In the eighteenth century this, too, disappeared in China, only to be rediscovered in the next century. The four elements, called heaven, earth, man, and matter, are the representations of four unknown quantities in the same equation. The book marks the peak in the development of Chinese algebra, for it deals with simultaneous equations and with equations of degrees as high as fourteen. In it the author describes a transformation method that he calls fan fa, the elements of which to have arisen long before in China, but which generally bears the name of Horner, who lived half a millennium later."

The Jade Mirror opens with a diagram of the arithmetic triangle (Pascal's triangle) using a round zero symbol, but Chu Shih-chieh denies credit for it. A similar triangle appears in Yang Hui's work, but without the zero symbol.[39]

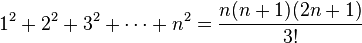

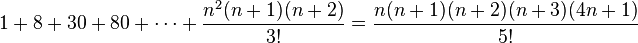

There are many summation series equations given without proof in the Precious mirror. A few of the summation series are:[39]

Mathematical Treatise in Nine Sections

Shu-shu chiu-chang, or Mathematical Treatise in Nine Sections, was written by the wealthy governor and minister Ch'in Chiu-shao (ca. 1202 – ca. 1261 AD) and with the invention of a method of solving simultaneous congruences, it marks the high point in Chinese indeterminate analysis.[38]

Magic Squares and Magic Circles

The earliest known magic squares of order greater than three are attributed to Yang Hui (fl. ca. 1261–1275), who worked with magic squares of order as high as ten.[40] He also worked with magic circle.

Trigonometry

The embryonic state of trigonometry in China slowly began to change and advance during the Song Dynasty (960–1279), where Chinese mathematicians began to express greater emphasis for the need of spherical trigonometry in calendarical science and astronomical calculations.[29] The polymath Chinese scientist, mathematician and official Shen Kuo (1031–1095) used trigonometric functions to solve mathematical problems of chords and arcs.[29] Victor J. Katz writes that in Shen's formula "technique of intersecting circles", he created an approximation of the arc of a circle s by s = c + 2v2/d, where d is the diameter, v is the versine, c is the length of the chord c subtending the arc.[41] Sal Restivo writes that Shen's work in the lengths of arcs of circles provided the basis for spherical trigonometry developed in the 13th century by the mathematician and astronomer Guo Shoujing (1231–1316).[42] As the historians L. Gauchet and Joseph Needham state, Guo Shoujing used spherical trigonometry in his calculations to improve the calendar system and Chinese astronomy.[29][43] Along with a later 17th-century Chinese illustration of Guo's mathematical proofs, Needham states that:

Guo used a quadrangular spherical pyramid, the basal quadrilateral of which consisted of one equatorial and one ecliptic arc, together with two meridian arcs, one of which passed through the summer solstice point...By such methods he was able to obtain the du lü (degrees of equator corresponding to degrees of ecliptic), the ji cha (values of chords for given ecliptic arcs), and the cha lü (difference between chords of arcs differing by 1 degree).[44]

Later developments

After the overthrow of the Yuan Dynasty, China became suspicious of knowledge it used. The Ming Dynasty turned away from math and physics in favor of botany and pharmacology.

At this period, the abacus which was first mentioned in the second century BC alongside 'calculation with rods' (suan zi)[9] now came into its suan pan form[45] and overtook the counting rods and became the preferred computing device. Zhu Zaiyu, Prince of Zheng who invented the equal temperament used 81 position abacus to calculate the square root and cubic root of 2 to 25 figure accuracy.

Although this switch from counting rods to the abacus allowed for reduced computation times, it may have also led to the stagnation and decline of Chinese mathematics. The pattern rich layout of counting rod numerals on counting boards inspired many Chinese inventions in mathematics, such as the cross multiplication principle of fractions and methods for solving linear equations. Similarly, Japanese mathematicians were influenced by the counting rod numeral layout in their definition of the concept of a matrix. However, during the Ming dynasty, mathematicians were fascinated with perfecting algorithms for the abacus. As such, many works devoted to abacus mathematics appeared in this period; at the expense of new idea creation.

Despite the achievements of Shen and Guo's work in trigonometry, another substantial work in Chinese trigonometry would not be published again until 1607, with the dual publication of Euclid's Elements by Chinese official and astronomer Xu Guangqi (1562–1633) and the Italian Jesuit Matteo Ricci (1552–1610).[46]

A revival of mathematics in China began in the late nineteenth century, when Joseph Edkins, Alexander Wylie and Li Shanlan translated works on astronomy, algebra and differential-integral calculus into Chinese, published by London Missionary Press in Shanghai.

Mathematical texts

Zhou Dynasty

Zhoubi Suanjing" c. 1000 BCE-100 CE -Astronomical theories, and computation techniques -Proof of the Pythagorean theorem (Shang Gao Theorem) -Fractional computations -Pythagorean theorem for astronomical purposes

Nine Chapters of Mathematical Arts1000 BCE? – 50 CE -ch.1, computational algorithm, area of plane figures, GCF, LCD -ch.2, proportions -ch.3, proportions -ch.4, square, cube roots, finding unknowns -ch.5, volume and usage of pi as 3 -ch.6, proportions -ch,7, interdeterminate equations -ch.8, Gaussian elimination and matrices -ch.9, Pythagorean theorem (Gougu Theorem)

Mathematics in education

The first reference to a book being used in learning mathematics in China is dated to the second century CE (Hou Hanshu: 24, 862; 35,1207). We are told that Ma Xu (a youth ca 110) and Zheng Xuan (127-200) both studied the Nine Chapters on Mathematical procedures. C.Cullen claims that mathematics, in a manner akin to medicine, was taught orally. The stylistics of the Suàn shù shū from Zhangjiashan suggest that the text was assembled from various sources and then underwent codification.[47]

See also

- Chinese astronomy

- History of mathematics

- Indian mathematics

- Islamic mathematics

- Japanese mathematics

Footnotes and references

This article incorporates text from Americanized Encyclopædia Britannica: rev. and amended A dictionary of arts, sciences and literature, to which is added biographies of living subjects. 96 colored maps and numerous illustrations, Volume 9, a publication from 1890 now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from Americanized Encyclopædia Britannica: rev. and amended A dictionary of arts, sciences and literature, to which is added biographies of living subjects. 96 colored maps and numerous illustrations, Volume 9, a publication from 1890 now in the public domain in the United States. This article incorporates text from The home encyclopædia: compiled and revised to date from the leading encyclopædias, Volume 18, a publication from 1895 now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from The home encyclopædia: compiled and revised to date from the leading encyclopædias, Volume 18, a publication from 1895 now in the public domain in the United States. This article incorporates text from Americanized Encyclopædia Britannica, revised and amended: A dictionary of arts, sciences and literature; to which is added biographies of livings subjects ..., a publication from 1890 now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from Americanized Encyclopædia Britannica, revised and amended: A dictionary of arts, sciences and literature; to which is added biographies of livings subjects ..., a publication from 1890 now in the public domain in the United States. This article incorporates text from The encyclopædia britannica: a dictionary of arts, sciences, literature and general information, Volume 26, by Hugh Chisholm, a publication from 1911 now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from The encyclopædia britannica: a dictionary of arts, sciences, literature and general information, Volume 26, by Hugh Chisholm, a publication from 1911 now in the public domain in the United States. This article incorporates text from The Encyclopædia Britannica: a dictionary of arts, sciences, and general literature, Volume 23, by Thomas Spencer Baynes, a publication from 1888 now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from The Encyclopædia Britannica: a dictionary of arts, sciences, and general literature, Volume 23, by Thomas Spencer Baynes, a publication from 1888 now in the public domain in the United States. This article incorporates text from The Encyclopædia Britannica: a dictionary of arts, sciences, literature and general information, Volume 26, by Hugh Chisholm, a publication from 1911 now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from The Encyclopædia Britannica: a dictionary of arts, sciences, literature and general information, Volume 26, by Hugh Chisholm, a publication from 1911 now in the public domain in the United States. This article incorporates text from The Encyclopædia britannica: a dictionary of arts, sciences, and general literature ; the R.S. Peale reprint, with new maps and original American articles, Volume 23, by William Harrison De Puy, a publication from 1893 now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from The Encyclopædia britannica: a dictionary of arts, sciences, and general literature ; the R.S. Peale reprint, with new maps and original American articles, Volume 23, by William Harrison De Puy, a publication from 1893 now in the public domain in the United States. This article incorporates text from The Life of the Buddha and the early history of his order: derived from Tibetan works in the Bkah-hgyur and Bstan-hgyur followed by notices on the early history of Tibet and Khoten, by Translated by William Woodville Rockhill, Ernst Leumann, Bunyiu Nanjio, a publication from 1907 now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from The Life of the Buddha and the early history of his order: derived from Tibetan works in the Bkah-hgyur and Bstan-hgyur followed by notices on the early history of Tibet and Khoten, by Translated by William Woodville Rockhill, Ernst Leumann, Bunyiu Nanjio, a publication from 1907 now in the public domain in the United States. This article incorporates text from The life of the Buddha: and the early history of his order, by William Woodville Rockhill, Ernst Leumann, Bunyiu Nanjio, a publication from 1884 now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from The life of the Buddha: and the early history of his order, by William Woodville Rockhill, Ernst Leumann, Bunyiu Nanjio, a publication from 1884 now in the public domain in the United States.

- ↑ Chinese overview

- ↑ Frank J. Swetz and T. I. Kao: Was Pythagoras Chinese?

- ↑ Needham, Volume 3, 91.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Needham, Volume 3, 92.

- ↑ Needham, Volume 3, 92-93.

- ↑ Needham, Volume 3, 93.

- ↑ Needham, Volume 3, 93-94.

- ↑ Needham, Volume 3, 94.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Ifrah, Georges (2001). The Universal History of Computing: From the Abacus to the Quantum Computer. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 978-0471396710.

- ↑ Brian Lander. “State Management of River Dikes in Early China: New Sources on the Environmental History of the Central Yangzi Region.” T’oung Pao 100.4-5 (2014): 351-352.

- ↑ Dauben, p 210.

- ↑ Boyer, 1991, "Chinese Math, China and India"

- ↑ Boyer, 1991, "Magic Square, China and India"

- ↑ Frank J. Swetz: The Sea Island Mathematical Manual, Surveying and Mathematics in Ancient China 4.2 Chinese Surveying Accomplishments, A Comparative Retrospection p63 The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1992 ISBN 0-271-00799-0

- ↑ Yoshio Mikami, The Development of Mathematics in China and Japan, chap 7, p. 50, reprint of 1913 edition Chelsea, NY, Library of Congress catalog 61–13497

- ↑ Lam Lay Yong, The Development of Hindu Arabic and Traditional Chinese Arithematic, Chinese Science, 13(1996) 35–54 [sic]

- ↑ Lam Lay Yong, The Development of Hindu Arabic and Traditional Chinese Arithematics

- ↑ Yoshio Mikami, Mathematics in China and Japan,p53

- ↑ Americanized Encyclopædia Britannica: rev. and amended A dictionary of arts, sciences and literature, to which is added biographies of living subjects. 96 colored maps and numerous illustrations, Volume 9. Belford-Clarke co. 1890. p. 5826. Retrieved 2011-07-01.Americanized Encyclopædia Britannica: Rev. and Amended A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences and Literature, to which is Added Biographies of Living Subjects. 96 Colored Maps and Numerous Illustrations

- ↑ The home encyclopædia: compiled and revised to date from the leading encyclopædias, Volume 18. Educational publishing co. 1895. p. 5826. Retrieved 2011-07-01.The Home Encyclopædia: Compiled and Revised to Date from the Leading Encyclopædias

- ↑ Americanized Encyclopædia Britannica, revised and amended: A dictionary of arts, sciences and literature; to which is added biographies of livings subjects ... The "Examiner". 1890. p. 5826. Retrieved 2011-07-01.Volume 9 of Americanized Encyclopædia Britannica, Revised and Amended: A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences and Literature; to which is Added Biographies of Livings Subjects

- ↑ Hugh Chisholm, ed. (1911). The encyclopædia britannica: a dictionary of arts, sciences, literature and general information, Volume 26 (11 ed.). At the University press. p. 926. Retrieved 2011-07-01.The Encyclopædia Britannica: A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature and General Information, Hugh Chisholm

- ↑ Thomas Spencer Baynes, ed. (1888). The Encyclopædia Britannica: a dictionary of arts, sciences, and general literature, Volume 23 (9 ed.). C. Scribner's sons. p. 345. Retrieved 2011-07-01.The Encyclopædia Britannica: A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and General Literature, Thomas Spencer Baynes

- ↑ Hugh Chisholm (1911). The Encyclopædia Britannica: a dictionary of arts, sciences, literature and general information, Volume 26 (11 ed.). The Encyclopædia Britannica Co. p. 926. Retrieved 2011-07-01.The Encyclopædia Britannica: A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature and General Information, Hugh Chisholm

- ↑ William Harrison De Puy (1893). The Encyclopædia britannica: a dictionary of arts, sciences, and general literature ; the R.S. Peale reprint, with new maps and original American articles, Volume 23 (9 ed.). Werner Co. p. 345. Retrieved 2011-07-01.The Encyclopædia Britannica: A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and General Literature ; the R.S. Peale Reprint, with New Maps and Original American Articles, William Harrison De Puy

- ↑ Translated by William Woodville Rockhill, Ernst Leumann, Bunyiu Nanjio (1907). The Life of the Buddha and the early history of his order: derived from Tibetan works in the Bkah-hgyur and Bstan-hgyur followed by notices on the early history of Tibet and Khoten. K. Paul, Trench, Trübner. p. 211. Retrieved 2011-07-01.

- ↑ William Woodville Rockhill, Ernst Leumann, Bunyiu Nanjio (1884). The life of the Buddha: and the early history of his order. Trübner & co. p. 211. Retrieved 2011-07-01.

- ↑ The Life of the Biddha and the Early History of His Order Derived from Tibetan Works in the Bkah-hgyur and Bstan-khoten. Taylor & Francis. p. 211. Retrieved 2011-07-01.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 29.4 Needham, Volume 3, 109.

- ↑ Needham, Volume 3, 108-109.

- ↑ Martzloff, 142

- ↑ Needham, Volume 3, 43.

- ↑ Needham, Volume 3, 62–63.

- ↑ Yoshio Mikami, The development of Mathematics in China and Japan, p77 Leipzig, 1912

- ↑ Ulrich Librecht,Chinese Mathematics in the Thirteenth Century p. 211 Dover 1973

- ↑ Needham, Volume 3, 134–137.

- ↑ Needham, Volume 3, 46.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 (Boyer 1991, "China and India" p. 204)

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 (Boyer 1991, "China and India" p. 205)

- ↑ (Boyer 1991, "China and India" pp. 204–205) "The same "Horner" device was used by Yang Hui, about whose life almost nothing is known and who work has survived only in part. Among his contributions that are extant are the earliest Chinese magic squares of order greater than three, including two each of orders four through eight and one each of orders nine and ten."

- ↑ Katz, 308.

- ↑ Restivo, 32.

- ↑ Gauchet, 151.

- ↑ Needham, Volume 3, 109–110.

- ↑ Yoshihide Igarashi, Tom Altman, Mariko Funada, Barbara Kamiyama (2014). Computing: A Historical and Technical Perspective. CRC Press. p. 64. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

- ↑ Needham, Volume 3, 110.

- ↑ Christopher Cullen, "Numbers, numeracy and the cosmos" in Loewe-Nylan, China's Early Empires, 2010:337-8.

Sources

- Boyer, C. B. (1989). A History of Mathematics. rev. by Uta C. Merzbach (2nd ed.). New York: Wiley,. ISBN 0-471-09763-2. (1991 pbk ed. ISBN 0-471-54397-7)

- Dauben, Joseph W. (2007). "Chinese Mathematics". In Victor J. Katz. The Mathematics of Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, India, and Islam: A Sourcebook. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-11485-9.

- Lander, Brian. “State Management of River Dikes in Early China: New Sources on the Environmental History of the Central Yangzi Region.” T’oung Pao 100.4-5 (2014): 325-62.

- Martzloff, Jean-Claude (1996). A History of Chinese Mathematics. Springer. ISBN 3-540-33782-2.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 3, Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd.

External links

- Early mathematics texts (Chinese) - Chinese Text Project

- Overview of Chinese mathematics

- Chinese Mathematics Through the Han Dynasty

- Primer of Mathematics by Zhu Shijie

| ||||||||||||||||||||||