Chinese Civil War

| Chinese Civil War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Clockwise from the top: Communist troops at the Battle of Siping, Muslim soldiers of the NRA, Mao Zedong in the 1930s, Chiang Kai-shek inspecting soldiers, CCP general Su Yu investigating the front field shortly before the Menglianggu Campaign | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

1927–1949

|

1927–1949 | ||||||

|

1949–1950 |

1949–1950 | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Chiang Kai-shek |

Mao Zedong | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

3,650,000 (June 1948) 1,490,000 (June 1949) |

1,200,000 (July 1945)[6] 4,000,000 (June 1949) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| ~1.5 million (1948–1949)[7] | ~250,000 (1948–1949)[7] | ||||||

|

1928–1936: ~2 million military casualties | |||||||

| Chinese Civil War | |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 國共內戰 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 国共内战 | ||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Nationalist-Communist Civil War | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| War of Liberation (mainland China) | |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 解放戰爭 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 解放战争 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Anti-Communist counter-insurgency war (Taiwan) | |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 反共戡亂戰爭 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 反共戡乱战争 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

The Chinese Civil War[nb 2] was a civil war in China fought between forces loyal to the Kuomintang (KMT) -led government of the Republic of China, and forces loyal to the Communist Party of China (CPC).[8] The war began in August 1927, with Chiang Kai-Shek's Northern Expedition, and essentially ended when major active battles ceased in 1950.[9] The conflict eventually resulted in two de facto states, the Republic of China (ROC) in Taiwan and the People's Republic of China (PRC) in mainland China, both claiming to be the legitimate government of China.

The war represented an ideological split between the Communist CPC, and the KMT's brand of Nationalism. The civil war continued intermittently until late 1937, when the two parties came together to form the Second United Front to counter a Japanese invasion. China's full-scale civil war resumed in 1946, a year after the end of hostilities with Japan. After four more years, 1950 saw the cessation of major military hostilities, with the newly founded People's Republic of China controlling mainland China (including Hainan), and the Republic of China's jurisdiction being restricted to Taiwan, Penghu, Quemoy, Matsu and several outlying islands.

Historian Odd Arne Westad says the Communists won the Civil War because they made fewer military mistakes than Chiang Kai-shek, and because in his search for a powerful centralized government, Chiang antagonized too many interest groups in China. Furthermore, his party was weakened in the war against the Japanese. Meanwhile the Communists targeted different groups, such as peasants, and brought them to its corner.[10] Chiang wrote in his diary in June 1948 that the KMT had failed, not because of external enemies but because of rot from within.[11] Strong initial support from the U.S. diminished with the failure of Marshall Mission, and then stopped completely primarily because of KMT corruption [12] (such as the notorious Yangtze Development Corporation [13] controlled by H. H. Kung and T. V. Soong's family) [14] and KMT's military setback in Northeast China. Communist land reform policy, which promised poor peasants farmland from their landlords, ensured PLA popular support. After the surrender of Japan at the end of World War II, Soviet forces turned over their captured Japanese weapons to the CPC and allowed the CPC to take control of territory in Manchuria, in which the Soviet Union was allowed to do so by the consent of the United States and the United Kingdom to intervene and influence the outcome of Chinese Civil War (especially in the decisive battles in Northeast China) at the expense of the Republic of China government by the result of Yalta Conference until the start of Cold War across the Taiwan Strait (see United Nations General Assembly Resolution 505). In the Chinese Civil War after 1945, economy in the ROC areas collapsed with hyperinflation and the failure of price-control by the ROC government with financial reform of Gold Yuan devaluated sharply in late 1948 [15] and resulted ROC government lost the loyal support of the cities' middle class supporters; whilst Communist Chinese continued relentless land reforms (land redistribution) to win the support of the population in the countryside. During the war both the Nationalist and Communists carried out mass atrocities with millions of non-combatants killed by both sides during the civil war.[16] Benjamin Valentino has estimated atrocities in the Chinese Civil War resulted in the death of between 1.8 million and 3.5 million people between 1927 and 1949. Atrocities include deaths from forced conscription and massacres.[17]

To this day, no armistice or peace treaty has ever been signed, and there is debate about whether the Civil War has legally ended.[18] Cross-Strait relations have been hindered by military threats and political and economic pressure, particularly over Taiwan's political status, with both governments officially adhering to a "One-China policy." The PRC still actively claims Taiwan as part of its territory and continues to threaten the ROC with a military invasion if the ROC officially declares independence by changing its name to and gaining international recognition as the Republic of Taiwan. The ROC mutually claims mainland China, and they both continue the fight over diplomatic recognition. Today, the war as such occurs on the political and economic fronts in the form of cross-Strait relations; however, the two separate de facto states have close economic ties.[19]

Background

The Qing Dynasty, the last of the ruling Chinese dynasties, collapsed in 1911 and finally fell in 1912 with the abdication of the last emperor.[19] China was left under the control of several major and lesser warlords in the Warlord era. The anti-monarchist and national unificationist Kuomintang party and its leader Sun Yat-sen, sought the help of foreign powers to defeat these warlords, who had seized control of much of Northern China,

Sun Yat-sen's efforts to obtain aid from the Western countries were ignored, however, and in 1921 he turned to the Soviet Union. For political expediency, the Soviet leadership initiated a dual policy of support for both Sun and the newly established Communist Party of China, which would eventually found the People's Republic of China. Thus the struggle for power in China began between the KMT and the CPC.

In 1923, a joint statement by Sun and Soviet representative Adolph Joffe in Shanghai pledged Soviet assistance for China's unification.[20] The Sun-Joffe Manifesto was a declaration for cooperation among the Comintern, KMT and the Communist Party of China.[20] Comintern agent Mikhail Borodin arrived in China in 1923 to aid in the reorganization and consolidation of the KMT along the lines of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. The CPC joined the KMT to form the First United Front.[6]

In 1923, Sun Yat-sen sent Chiang Kai-shek, one of his lieutenants from his Tongmeng Hui days, for several months of military and political study in Moscow.[21] By 1924, Chiang became the head of the Whampoa Military Academy, and rose to prominence as Sun's successor as head of the KMT.[21]

The Soviets provided much of the studying material, organization, and equipment including munitions for the academy.[21] The Soviets also provided education in many of the techniques for mass mobilization. With this aid Sun Yat-sen was able to raise a dedicated "army of the party," with which he hoped to defeat the warlords militarily. CPC members were also present in the academy, and many of them became instructors, including Zhou Enlai who was made a political instructor of the academy.[22]

Communist members were allowed to join the KMT on an individual basis.[20] The CPC itself was still small at the time, having a membership of 300 in 1922 and only 1,500 by 1925.[23] The KMT in 1923 had 50,000 members.[23]

Northern Expedition and KMT-CPC split

In early 1927 the KMT-CPC rivalry led to a split in the revolutionary ranks. The CPC and the left wing of the KMT had decided to move the seat of the KMT government from Guangzhou to Wuhan, where communist influence was strong.[23] But Chiang and Li Zongren, whose armies defeated warlord Sun Chuanfang, moved eastward toward Jiangxi. The leftists rejected Chiang's demand to eliminate Communists influence within KMT and Chiang denounced the leftists for betraying Sun Yat-sen's Three Principles of the People by taking orders from the Soviet Union. According to Mao Zedong, Chiang's tolerance of the CPC in the KMT camp decreased as his power increased.[24]

On April 7, Chiang and several other KMT leaders held a meeting arguing that communist activities were socially and economically disruptive, and must be undone for the national revolution to proceed.

On April 12 in Shanghai, the KMT was purged of leftists by the arrest and execution of hundreds of CPC members.[25] It was directed by General Bai Chongxi. This was called the April 12 Incident or Shanghai Massacre by the CPC.[26] The Shanghai massacre widened the rift between Chiang and Wang Jingwei's Wuhan.

Eventually left-wing KMT also expelled CPC from the Wuhan government, who in turn were toppled by Chiang Kai-shek. The KMT resumed the campaign against warlords and captured Beijing in June 1928.[27] Afterwards most of eastern China was under the Nanjing central government's control, and the Nanjing government received prompt international recognition as the sole legitimate government of China. The KMT government announced in conformity with Sun Yat-sen, the formula for the three stages of revolution: military unification, political tutelage, and constitutional democracy.[28]

Communist insurgency (1927–1937)

During the 1920s, Communist Party of China activists retreated underground or to the countryside where they fomented an armed rebellion. The revolt of the CPC against the Nationalist government began on 1 August 1927 in Nanchang, Jiangxi.[1][29] The Nanchang Uprising saw the formation of a communist rebel army, which would later become the People's Liberation Army. After a few days, government forces reclaimed Nanchang, while surviving rebels escaped into the countryside.[1] Later, attempts were made by CPC to take the cities of Changsha, Shantou, and Guangzhou. The communist force consisted of mutinied soldiers as well as armed peasant. They established control over several areas in southern China.[29] The Guangzhou commune was able to control Guangzhou for three days and a "soviet" was established.[29] KMT armies continued to suppress the rebellions.[29] This marked the beginning of the ten year's struggle, known in mainland China as the "Ten Year's Civil War" (Traditional Chinese: 十年內戰 Simplified Chinese:十年内战 Pinyin:Shínían Nèizhàn). It lasted until the Xi'an Incident when Chiang Kai-shek was forced to form the Second United Front against the invading Japanese. An armed rural insurrection, known as the Autumn Harvest Uprising was staged by peasants, miners and CPC members in Hunan Province led by Mao Zedong.[30] The uprising was unsuccessful.[30] There were now three capitals in China: the internationally recognized republic capital in Beijing, the CPC and left-wing KMT at Wuhan and the right-wing KMT regime at Nanjing, which would remain the KMT capital for the next decade.[31][31][32]

In 1930 the Central Plains War broke out as an internal conflict of the KMT. It was launched by Feng Yuxiang, Yan Xishan, and Wang Jingwei. The attention was turned to root out remaining pockets of Communist activity in a series of encirclement campaigns. There were a total of five campaigns.[33] The first and second campaigns failed and the third was aborted due to the Mukden Incident. The fourth campaign (1932–1933) achieved some early successes, but Chiang’s armies were badly mauled when they tried to penetrate into the heart of Mao’s Soviet Chinese Republic. During these campaigns, the KMT columns struck swiftly into Communist areas, but were easily engulfed by the vast countryside and were not able to consolidate their foothold.

Finally, in late 1934, Chiang launched a fifth campaign that involved the systematic encirclement of the Jiangxi Soviet region with fortified blockhouses.[34] Unlike in previous campaigns in which they penetrated deeply in a single strike, this time the KMT troops patiently built blockhouses, each separated by five or so miles to surround the Communist areas and cut off their supplies and food source.[34]

In October 1934, the CPC took advantage of gaps in the ring of blockhouses (manned by the troops of a warlord ally of Chiang Kai-shek's, rather than the KMT themselves) to escape Jiangxi. The warlord armies were reluctant to challenge Communist forces for fear of wasting their own men, and did not pursue the CPC with much fervor. In addition, the main KMT forces were preoccupied with annihilating Zhang Guotao's army, which was much larger than Mao's. The massive military retreat of Communist forces lasted a year and covered what Mao estimated as 12,500 km (25,000 Li), and became known as the Long March.[35]

The march ended when the CPC reached the interior of Shaanxi. Zhang Guotao's army, which took a different route through northwest China, was largely destroyed by the forces of Chiang Kai-shek and his Chinese Muslim ally, the Ma clique. Along the way, the Communist army confiscated property and weapons from local warlords and landlords, while recruiting peasants and the poor, solidifying its appeal to the masses. Of the 90,000-100,000 people who began the Long March from the Soviet Chinese Republic, only around 7,000-8,000 made it to Shaanxi.[36] The remnants of Zhang's forces eventually joined Mao in Shaanxi, but with his army destroyed, Zhang, even as a founding member of the CPC, was never able to challenge Mao's authority. Essentially, the great retreat made Mao the undisputed leader of the Communist Party of China.

The Kuomintang used Khampa soldiers to battle the Communist Red Army as it advanced, and to undermine local warlords who often refused to fight Communist forces to conserve their own strength. 300 "Khampa bandits" were enlisted into the Kuomintang's Consolatory Commission military in Sichuan, where they were part of the effort of the central government of China to penetrate and destabilize the local Han warlords such as Liu Wenhui. The Chinese government sought to exercise full control over frontier areas against the warlords. Liu had refused to battle the Communists to conserve his army. The Consoltary Commission forces were used to battle the Communist Red Army, but were defeated when their religious leader was captured by Communist forces.[37]

-

Situation in China in 1929: After the Northern Expedition, the KMT had direct control over China's central east, while the rest of China proper and Manchuria was under the control of warlords loyal to the Nationalist government.

-

Movement of Communist forces during the long march

-

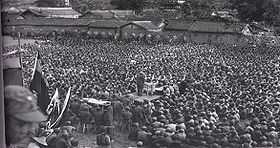

A Communist leader addressing Long March survivors.

Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945)

During the Japanese invasion and occupation of Manchuria, Chiang Kai-shek, who saw the CPC as a greater threat, refused to ally with the CPC to fight against the Imperial Japanese Army. Chiang preferred to unite China by eliminating the warlords and CPC forces first. Chiang believed that he was still too weak to launch an offensive to chase out Japan and that China needed time for a military build-up. Only after unification would it be possible for the KMT to mobilize a war against Japan. So he would rather ignore the discontent and anger among Chinese people at his policy of compromise with the Japanese, and ordered KMT Generals Zhang Xueliang and Yang Hucheng to carry out suppression of the CPC and their provincial forces suffered significant casualties in battles with the Red Army.ref

On December 12, 1936, the disgruntled Zhang Xueliang and Yang Hucheng conspired to kidnap Chiang Kai-shek and then force him into a truce with the CPC. The incident became known as the Xi'an Incident.[38] Both parties suspended fighting to form a Second United Front to focus their energies and fighting against the Japanese.[38] In 1937, Japan launched its full-scale invasion of China and its well-equipped troops overran KMT defenders in north and coastal China.

The alliance of CPC and KMT was in name only.[39] Unlike the KMT troops, CPC shunned conventional warfare and instead engaged in guerrilla warfare against the Japanese. The level of actual cooperation and coordination between the CPC and KMT during World War II was at best minimal.[39] In the midst of the Second United Front, the CPC and the KMT were still vying for territorial advantage in "Free China" (i.e. areas not occupied by the Japanese or ruled by Japanese puppet governments such as Manchukuo and the Reorganized National Government of China).[39]

The situation came to a head in late 1940 and early 1941 when clashes between the Communist and KMT forces intensified. In December 1940, Chiang Kai-shek demanded that the CPC’s New Fourth Army evacuate Anhui and Jiangsu Provinces due to CPC's provocation and harassment of KMT forces in this area. Under intense pressure, the New Fourth Army commanders complied. In 1941 they were ambushed by KMT forces during their evacuation, which led to several thousand deaths in the CPC.[40] It also ended the Second United Front which had been formed earlier to fight the Japanese.[40]

Despite of the intensified ambiance between the CPC and KMT, the external countries such as United States and Soviet Union attempted to prevent a disastrous civil war. After the New Fourth Army incident, President Roosevelt sent special envoy Lauchlin Currie to talk with Chiang Kai-shek and KMT party leaders to express their concern regarding the hostility between the two parties, with Currie stating that the civil war would only be of benefit the Japanese. In 1941, the Soviet Union with its closer alliance to the CPC also sent an imperative telegram to Mao warning that the civil war would also make the situation easier for Japanese military. Due to the international community's efforts, the war did meet a temporary and superficial peace. However, the hardships were meaningless considering the two parties' urgent agenda included preparing for a showdown following the defeat of Japan. In 1943, Chiang attacked the CPC within the propaganda piece China's Destiny which questioned the CPC's power after the war, while the CPC strongly opposed Chiang's leadership and referred to his regime as fascist in an attempt to generate a negative public image. Overall, both leaders simply knew a deadly battle begun between themselves, and at the same time, Chinese domestic security was shaken by two leading parties.[41]

In general, developments in the Second Sino-Japanese War were to the advantage of the CPC, as their guerilla war effort had won them popular support within the Japanese-occupied areas while the KMT's burden to defend China against main Japanese assaults due to its status as the legal government of China proved costly to Chiang Kai-shek and his troops. In 1944 Japan launched its last major offensive, Operation Ichi-Go, against the KMT that severely weakened Chiang Kai-shek's forces.[42]

Immediate post-war clashes (1945–1946)

Under the terms of the Japanese unconditional surrender dictated by the United States, Japanese troops were ordered to surrender to KMT troops and not to the CPC present in some of the occupied areas.[43] In Manchuria, however, where the KMT had no forces, the Japanese surrendered to the Soviet Union. Chiang Kai-Shek ordered the Japanese troops to remain at their post to receive the Kuomintang and not surrender their arms to the communists.[43]

The first post-war peace negotiation was attended by both Chiang Kai-shek and Mao Zedong in Chongqing from 28 August 1945 and concluded on 10 October 1945 with the signing of Double Tenth Agreement.[44] Both sides stressed the importance of a peaceful reconstruction, but the conference did not produce any concrete result.[44] Battles between the two sides continued even as the peace negotiation was in progress, until the agreement was reached in January 1946. However, large campaigns and full scale confrontations between the CPC and Chiang's own troops were temporarily avoided.

In the last month of World War II in East Asia, Soviet forces launched the mammoth Manchurian Strategic Offensive Operation to attack the Japanese in Manchuria and along the Chinese-Mongolian border.[45] This operation destroyed the fighting capability of the Kwantung Army and left the USSR in occupation of all of Manchuria by the end of the war. Consequently, the 700,000 Japanese troops stationed in the region surrendered. Later in the year, Chiang Kai-shek realized that he lacked the resources to prevent a CPC takeover of Manchuria following the scheduled Soviet departure.[46]

He therefore made a deal with the Russians to delay their withdrawal until he had moved enough of his best-trained men and modern material into the region; however the Russians refused permission for the Nationalist troops to traverse its territory. KMT troops were then airlifted by the United States to occupy key cities in North China, while the countryside was already dominated by the CPC. On November 15, 1945 an offensive begins with the intent of preventing the CPC from strengthening their already strong base.[47] The Soviets spent the extra time systematically dismantling the extensive Manchurian industrial base (worth up to 2 billion dollars) and shipping it back to their war-ravaged country.[46]

Yang Kuisong, a Chinese historian, said in the 1945-1946, during the Soviet Red Army Manchurian campaign, Stalin commanded Marshal Rodion Malinovsky to give Mao Zedong some Imperial Japanese Army weapons that were captured.[48]

Chiang Kai-Shek's forces pushed as far as Chinchow, by November 26, 1945, meeting with little resistance. This was followed by a Communist offensive on the Shantung Peninsula that was largely successful, as all of the peninsula, except what was controlled by the US, fell to the Communists.[47] The truce fell apart in June 1946, when full-scale war between CPC and KMT broke out on June 26. China then entered a state of civil war that lasted more than three years.[49]

Resumed fighting (1946–1950)

Background and disposition of forces

By the end of the Second Sino-Japanese War, the balance of power in China's civil war had shifted in favour of the Communists. Their main force grew to 1.2 million troops, with a militia of 2 million. Their "Liberated Zone" contained 19 base areas, including 1/4 of the country's territory and 1/3 of its population; this included many important towns and cities. Moreover, the Soviet Union turned over all of their captured Japanese weapons and a substantial amount of their own supplies to the Communists, who received Northeastern China from the Soviets as well.[50]

In March 1946, despite repeated requests from Chiang, the Soviet Red Army under the command of Marshal Malinovsky continued to delay pulling out of Manchuria while he secretly told the CPC forces to move in behind them, because Stalin wanted Mao to have firm control of at least the northern part of Manchuria before the complete withdrawal of the Soviets, which led to full-scale war for the control of the Northeast. These favourable conditions also facilitated many changes inside the Communist leaders: the more hard-line and firmer force finally gained the upper hand and defeated the opportunists.[50][51] Prior to giving control to Communist leaders, on March 27, Soviet diplomat requested joint venture of industrial development with the Nationalist Party in Manchuria.[52]

Although General Marshall stated that he knew of no evidence that the CPC were being supplied by the Soviet Union, the CPC were able to capture a large number of weapons abandoned by the Japanese, including some tanks but it was not until large numbers of well trained KMT troops surrendered and joined the communist forces that the CPC were finally able to master the hardware.[53][54] But despite the disadvantage in military hardware, the CPC's ultimate trump card was its land reform policy. The CPC continued to make the irresistible promise in the countryside to the massive number of landless and starving Chinese peasants that by fighting for the CPC they would be able to take farmland from their landlords.[55]

This strategy enabled the CPC to access an almost unlimited supply of manpower to use in combat as well as provide logistic support, despite suffering heavy casualties throughout many civil war campaigns. For example, during the Huaihai Campaign alone the CPC were able to mobilize 5,430,000 peasants to fight against the KMT forces.[56]

After the war with the Japanese ended, Chiang Kai-shek quickly moved KMT troops to newly liberated areas to prevent Communist forces from receiving the Japanese surrender.[50] The United States airlifted many KMT troops from central China to the Northeast (Manchuria). President Truman was very clear about what he described as "using the Japanese to hold off the Communists". In his memoirs he writes:

It was perfectly clear to us that if we told the Japanese to lay down their arms immediately and march to the seaboard, the entire country would be taken over by the Communists. We therefore had to take the unusual step of using the enemy as a garrison until we could airlift Chinese National troops to South China and send Marines to guard the seaports.—President Truman[57]

Using the pretext of "receiving the Japanese surrender", business interests within the KMT government occupied most of the banks, factories and commercial properties, which had previously been seized by the Imperial Japanese Army.[50] They also recruited troops at a brutal pace from the civilian population and hoarded supplies, preparing for a resumption of war with the Communists. These hasty and harsh preparations caused great hardship for the residents of cities such as Shanghai, where the unemployment rate rose dramatically to 37.5%.[50]

The United States strongly supported the Kuomintang forces. Over 50,000 Marines were sent to guard strategic sites, and 100,000 US troops were sent to Shandong. The US equipped and trained over 500,000 KMT troops, and transported KMT forces to occupy newly liberated zones, as well as to contain Communist controlled areas.[50] American aid included substantial amounts of both new and surplus military supplies; additionally, loans worth hundreds of millions of dollars were made to the KMT.[58] Within less than 2 years after the Sino-Japanese War, the KMT had received 4.43 billion dollars from the US - most of which was military aid.[50]

Outbreak of War

-

Situation in 1947

-

Situation in the fall of 1948

-

Situation in the winter of 1948 and 1949

-

Situation in April to October 1949

With the breakdown of talks, all-out war resumed. This stage is referred to in mainland China and Communist historiography as the "War of Liberation" (Chinese: 解放战争; pinyin: Jiěfàng Zhànzhēng). On 20 July 1946, Chiang Kai-shek launched a large-scale assault on Communist territory with 113 brigades (1.6 million troops).[50] This marked the final phase of the Chinese Civil War.

Knowing their disadvantages in manpower and equipment, the CPC executed a "passive defense" strategy. They avoided the strong points of the KMT army, and were prepared to abandon territory in order to preserve their forces. In most cases, the surrounding countryside and small towns had come under Communist influence long before the cities. They also attempted to wear out the KMT forces as much as possible. This tactic seemed to be successful; after a year, the power balance became more favorable to the CPC. They wiped out 1.12 million KMT troops, while their strength grew to about 2 million men.[50]

In March 1947, the KMT achieved a symbolic victory by seizing the CPC capital of Yan'an.[59] Soon after, the Communists counterattacked; on 30 June 1947, CPC troops crossed the Huanghe river and moved to Dabie Mountains area, restored and developed the Central Plain. Concurrently, Communist forces in Northeastern China, North China and East China began to counterattack as well.[50]

By late 1948 the CPC eventually captured the northern cities of Shenyang and Changchun and seized control of the Northeast after struggling through numerous set-backs while trying to take the cities, with the decisive Liaoshen Campaign.[60] The New 1st Army, regarded as the best KMT army, had to surrender after the CPC conducted a deadly 6-month siege of Changchun that resulted in more than 150,000 civilian deaths from starvation.[61]

The capture of large KMT formations provided them with the tanks, heavy artillery, and other combined-arms assets needed to prosecute offensive operations south of the Great Wall. By April 1948 the city of Luoyang fell, cutting the KMT army off from Xi'an.[62] Following a fierce battle, the CPC captured Jinan and Shandong province on September 24, 1948. The Huaihai Campaign of late 1948 and early 1949 secured east-central China for the CPC.[60] The outcome of these encounters were decisive for the military outcome of the civil war.[60]

The Pingjin Campaign resulted in the Communist conquest of northern China lasting 64 days from November 21, 1948, to January 31, 1949.[63] The People's Liberation Army suffered heavy casualties from securing Zhangjiakou, Tianjin along with its port and garrison at Dagu and Beiping.[63] The CPC brought 890,000 troops from the Northeast to oppose some 600,000 KMT troops.[62] There were 40,000 CPC casualties at Zhangjiakou alone. They in turn killed, wounded or captured some 520,000 KMT during the campaign.[63]

After the three decisive Liaoshen, Huaihai and Pingjin campaigns, the CPC wiped out 144 regular and 29 non-regular KMT divisions, including 1.54 million veteran KMT troops. This effectively smashed the backbone of the KMT army.[50]

On 21 April, Communist forces crossed the Yangtze River, and on 23 April they captured the KMT's capital, Nanjing.[35] The KMT government retreated to Canton (Guangzhou) until October 15, Chongqing until November 25, and then Chengdu before retreating to Taiwan on December 10. By late 1949, the People's Liberation Army was pursuing remnants of KMT forces southwards in southern China, and only Tibet was left.

In addition, the Ili Rebellion was a Soviet backed revolt by the Second East Turkestan Republic against the KMT from 1944-1949 as the Mongolians in the People's Republic were in a border dispute with the Republic of China. A Chinese Muslim Hui cavalry regiment, the 14th Tungan Cavalry regiment, was sent by the Chinese government to attack Mongol and Soviet positions along the border during the Pei-ta-shan Incident.[64][65]

Several last-ditch attempts by the Kuomintang to use Khampa soldiers against the Communists in southwest China were set up. The Kuomintang formulated a plan where 3 Khampa divisions would be assisted by the Panchen Lama to oppose the Communists.[66] Kuomintang intelligence reported that some Tibetan tusi chiefs and the Khampa Su Yonghe controlled 80,000 troops in Sichuan, Qinghai, and Tibet. They hoped to use them against the Communist army.[67]

Fighting subsides

On October 1, 1949, Mao Zedong proclaimed the People's Republic of China with its capital at Beiping, which was renamed Beijing. Chiang Kai-shek and approximately 2 million Nationalist Chinese retreated from mainland China to the island of Taiwan in December after the loss of Sichuan. There remained only isolated pockets of resistance, notably in Sichuan (ending soon after the fall of Chengdu on December 10, 1949) and in the far south.[68]

A PRC attempt to take the ROC controlled island of Quemoy was thwarted in the Battle of Kuningtou halting the PLA advance towards Taiwan.[69] In December 1949, Chiang proclaimed Taipei, Taiwan, the temporary capital of the Republic of China and continued to assert his government as the sole legitimate authority in China.

The Communists' other amphibious operations of 1950 were more successful: they led to the Communist conquest of Hainan Island in April 1950, capture of Wanshan Islands off the Guangdong coast (May–August 1950) and of Zhoushan Island off Zhejiang (May 1950).[70]

Aftermath

Most observers expected Chiang's government to eventually fall in response to a Communist invasion of Taiwan, and the United States initially showed no interest in supporting Chiang's government in its final stand. Things changed radically with the onset of the Korean War in June 1950. At this point, allowing a total Communist victory over Chiang became politically impossible for the United States, and President Harry S. Truman ordered the United States Seventh Fleet into the Taiwan Strait to prevent the ROC and PRC from attacking each other.[71]

In June 1949, the ROC declared a "closure" of all mainland China ports and its navy attempted to intercept all foreign ships. The closure covered from a point north of the mouth of Min River in Fujian to the mouth of the Liao River in Liaoning.[72] Since mainland China's railroad network was underdeveloped, north-south trade depended heavily on sea lanes. ROC naval activity also caused severe hardship for mainland China fishermen.

After losing mainland China, a group of approximately 12,000 KMT soldiers escaped to Burma and continued launching guerrilla attacks into south China during the Kuomintang Islamic Insurgency in China (1950–1958) and Campaign at the China–Burma Border. Their leader, General Li Mi, was paid a salary by the ROC government and given the nominal title of Governor of Yunnan. Initially, the United States supported these remnants and the Central Intelligence Agency provided them with aid. After the Burmese government appealed to the United Nations in 1953, the U.S. began pressuring the ROC to withdraw its loyalists. By the end of 1954, nearly 6,000 soldiers had left Burma and Li Mi declared his army disbanded. However, thousands remained, and the ROC continued to supply and command them, even secretly supplying reinforcements at times.

After the ROC complained to the United Nations against the Soviet Union for violating the Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship and Alliance to support the CPC, the UN General Assembly Resolution 505 was adopted on February 1, 1952 to condemn the Soviet Union.

Though viewed as a military liability by the United States, the ROC viewed its remaining islands in Fujian as vital for any future campaign to defeat the PRC and retake mainland China. On September 3, 1954, the First Taiwan Strait Crisis began when the PLA started shelling Quemoy and threatened to take the Dachen Islands in Zhejiang.[72] On January 20, 1955, the PLA took nearby Yijiangshan Island, with the entire ROC garrison of 720 troops killed or wounded defending the island. On January 24 of the same year, the United States Congress passed the Formosa Resolution authorizing the President to defend the ROC's offshore islands.[72] The First Taiwan Straits crisis ended in March 1955 when the PLA ceased its bombardment. The crisis was brought to a close during the Bandung conference.[72]

The Second Taiwan Strait Crisis began on August 23, 1958 with air and naval engagements between the PRC and the ROC military forces, leading to intense artillery bombardment of Quemoy (by the PRC) and Amoy (by the ROC), and ended on November of the same year.[72] PLA patrol boats blockaded the islands from ROC supply ships. Though the United States rejected Chiang Kai-shek's proposal to bomb mainland China artillery batteries, it quickly moved to supply fighter jets and anti-aircraft missiles to the ROC. It also provided amphibious assault ships to land supplies, as a sunken ROC naval vessel was blocking the harbor. On September 7, the United States escorted a convoy of ROC supply ships and the PRC refrained from firing.

Despite the end of the hostilities, the two sides have never signed any agreement or treaty to officially end the war.

By 1984, PRC and ROC had public contacts with each other and cross-straits trade and investment has been growing ever since. Although the Taiwan straits remain a potential flash point, regular direct air links were established in 2009.[19]

The Third Taiwan Strait Crisis in 1995–96 escalated tensions between both sides when the PRC tested a series of missiles not far from Taiwan although, arguably, Beijing ran the test to shift the 1996 presidential election vote in favor of the KMT, already facing a challenge from the opposition Democratic Progressive Party which did not agree with the "One China Policy" shared by the CPC and KMT.[73]

The war was officially declared over by the ROC in 1991.[74]

With the election in 2000 of the Democratic Progressive Party candidate Chen Shui-bian, a party other than the KMT gained the presidency for the first time in Taiwan. The new president did not share the Chinese nationalist ideology of the KMT and CPC. This led to tension between the two sides although trade and other ties such as the 2005 Pan-Blue visit continued to increase.

Since the election of President Ma Ying-jeou (KMT) in 2008, significant warming of relations has resumed between Taipei and Beijing with high level exchanges between the semi-official diplomatic organizations of both states such as the Chen-Chiang summit series.

Footnotes

- ↑ The conflict did not have an official end date. However, historians generally agree that the war subsided after the fall of Hainan and Zhoushan archipelago in May 1950, the KMT's last major stronghold near the mainland.[4]

- ↑ In mainland China today, the last three years of the war (1947–1949) are more commonly known as the War of Liberation (解放战争), or alternatively the Third Internal Revolutionary War (第三次国内革命战争). In Taiwan, the war was also known as the Counter-insurgency War against Communists (反共戡亂戰爭) before 1991 or commonly the Nationalist-Communist Civil War (國共內戰) in both sides.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 China at War: An Encyclopedia. 2012. p. 295.

- ↑ "China". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 15 November 2012.

- ↑ Gui, Heng Bin (2008). Landing on Hainan Island. China: Great Wall Press. ISBN 9787548300755.

- ↑ Westad, Odd (2003). Decisive Encounters: The Chinese Civil War, 1946-1950. Stanford University Press. p. 305. ISBN 978-0-8047-4484-3.

- ↑ Èëãñèõ±¨

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Hsiung, James C. (1992). China's Bitter Victory: The War With Japan, 1937-1945. New York: M.E. Sharpe publishing. ISBN 1-56324-246-X.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Michael Lynch (2010). The Chinese Civil War 1945-49. Osprey Publishing. p. 91. ISBN 978-1-84176-671-3.

- ↑ Gay, Kathlyn. [2008] (2008). 21st Century Books. Mao Zedong's China. ISBN 0-8225-7285-0. pg 7

- ↑ Hutchings, Graham. [2001] (2001). Modern China: A Guide to a Century of Change. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-00658-5.

- ↑ Odd Arne Westad, Restless Empire: China and the World Since 1750 (2012) p 291.

- ↑ Hoover Institution – Hoover Digest – Chiang Kai-shek and the Struggle for China

- ↑ http://www.ea.sinica.edu.tw/eu_file/12010586724.pdf

- ↑ http://media.hoover.org/sites/default/files/documents/soong_register.pdf

- ↑ http://big5.backchina.com/blog/323944/article-142137.html

- ↑ http://www.mof.gov.tw/museum/ct.asp?xItem=3682&ctNode=34

- ↑ Rummel, Rudolph (1994), Death by Government.

- ↑ Valentino, Benjamin A. Final solutions: mass killing and genocide in the twentieth century Cornell University Press. December 8, 2005. p88

- ↑ Leslie C. Green. The Contemporary Law of Armed Conflict. p. 79.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 So, Alvin Y. Lin, Nan. Poston, Dudley L. Contributor Professor, So, Alvin Y. [2001] (2001). The Chinese Triangle of Mainland China, Taiwan and Hong Kong. Greenwood Publishing. ISBN 0-313-30869-1.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 March, G. Patrick. Eastern Destiny: Russia in Asia and the North Pacific. [1996] (1996). Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-275-95566-4. pg 205.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Chang, H. H. Chang. [2007] (2007). Chiang Kai Shek - Asia's Man of Destiny. ISBN 1-4067-5818-3. pg 126

- ↑ Ho, Alfred K. Ho, Alfred Kuo-liang. [2004] (2004). China's Reforms and Reformers. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-275-96080-3. pg 7.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Fairbank, John King. [1994] (1994). China: A New History. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-11673-9.

- ↑ Zedong, Mao. Thompson, Roger R. [1990] (1990). Report from Xunwu. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-2182-3.

- ↑ Brune, Lester H. Dean Burns, Richard Dean Burns. [2003] (2003). Chronological History of U.S. Foreign Relations. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-93914-3.

- ↑ Zhao, Suisheng. [2004] (2004). A Nation-state by Construction: Dynamics of Modern Chinese Nationalism. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-5001-7.

- ↑ Guo, Xuezhi. [2002] (2002). The Ideal Chinese Political Leader: A Historical and Cultural Perspective. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-275-97259-3.

- ↑ Theodore De Bary, William. Bloom, Irene. Chan, Wing-tsit. Adler, Joseph. Lufrano Richard. Lufrano, John. [1999] (1999). Sources of Chinese Tradition. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-10938-5. pg 328.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 Lee, Lai to. Trade Unions in China: 1949 To the Present. [1986] (1986). National University of Singapore Press. ISBN 9971-69-093-4.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Blasko, Dennis J. [2006] (2006). The Chinese Army Today: Tradition and Transformation for the 21st Century. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-77003-3.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Esherick, Joseph. [2000] (2000). Remaking the Chinese City: Modernity and National Identity, 1900–1950. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-2518-7.

- ↑ Clark, Anne Biller. Clark, Anne Bolling. Klein, Donald. Klein, Donald Walker. [1971] (1971). Harvard Univ. Biographic Dictionary of Chinese communism. Original from the University of Michigan v.1. Digitized Dec 21, 2006. p 134.

- ↑ Lynch, Michael Lynch. Clausen, Søren. [2003] (2003). Mao. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-21577-3.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Manwaring, Max G. Joes, Anthony James. [2000] (2000). Beyond Declaring Victory and Coming Home: The Challenges of Peace and Stability operations. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-275-96768-9. pg 58

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Zhang, Chunhou. Vaughan, C. Edwin. [2002] (2002). Mao Zedong as Poet and Revolutionary Leader: Social and Historical Perspectives. Lexington books. ISBN 0-7391-0406-3. p 65, p 58

- ↑ Bianco, Lucien. Bell, Muriel. [1971] (1971). Origins of the Chinese Revolution, 1915–1949. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-0827-4. pg 68

- ↑ Hsiao-ting Lin (2010). Modern China's ethnic frontiers: a journey to the west. Volume 67 of Routledge studies in the modern history of Asia (illustrated ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 52. ISBN 0-415-58264-4. Retrieved 2011-12-27.

A force of about 300 soldiers was organized and augmented by recruiting local Khampa bandits into the army. The relationship between the Consolatory Commission and Liu Wenhui seriously deteriorated in early 1936, when the Norla Hutuktu

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Ye, Zhaoyan Ye, Berry, Michael. [2003] (2003). Nanjing 1937: A Love Story. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-12754-5.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 Buss, Claude Albert. [1972] (1972). Stanford Alumni Association. The People's Republic of China and Richard Nixon. United States.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Schoppa, R. Keith. [2000] (2000). The Columbia Guide to Modern Chinese History. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-11276-9.

- ↑ Chen, Jian. [2001] (2001). Mao's China and the Cold War. The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-807-84932-4.

- ↑ Lary, Diana. [2007] (2007). China's Republic. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-84256-5.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Zarrow, Peter Gue. [2005] (2005). China in War and Revolution, 1895–1949. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-36447-7. pg 338.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Xu, Guangqiu. [2001] (2001). War Wings: The United States and Chinese Military Aviation, 1929–1949. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-32004-7. pg 201.

- ↑ Bright, Richard Carl. [2007] (2007). Pain and Purpose in the Pacific: True Reports of War. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 1-4251-2544-1.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Lilley, James. China hands : nine decades of adventure, espionage, and diplomacy in Asia , PublicAffairs, New York, 2004

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Jessup, John E. (1989). A Chronology of Conflict and Resolution, 1945-1985. New York: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-24308-5.

- ↑ 杨奎松《读史求实》:苏联给了林彪东北野战军多少现代武器

- ↑ Hu, Jubin. [2003] (2003). Projecting a Nation: Chinese National Cinema Before 1949. Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 962-209-610-7.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 50.3 50.4 50.5 50.6 50.7 50.8 50.9 50.10 Nguyễn Anh Thái (chief author); Nguyễn Quốc Hùng; Vũ Ngọc Oanh; Trần Thị Vinh; Đặng Thanh Toán; Đỗ Thanh Bình (2002). Lịch sử thế giới hiện đại (in Vietnamese). Ho Chi Minh City: Giáo Dục Publisher. pp. 320–322. 8934980082317.

- ↑ Michael M Sheng, Battling Western Imperialism, Princeton University Press, 1997, p.132 - 135

- ↑ Liu, Shiao Tang (1978). Min Kuo Ta Shih Jih Chih vol 2. Taipei: Zhuan Chi Wen Shuan. p. 735.

- ↑ New York Times, 12 January 1947, p44.

- ↑ Zeng Kelin, Zeng Kelin jianjun zishu (General Zeng Kelin Tells his story), Liaoning renmin chubanshe, Shenyang, 1997. p. 112-3

- ↑ Ray Huang, cong dalishi jiaodu du Jiang Jieshi riji (Reading Chiang Kai-shek's diary from a macro-history perspective), Chinatimes Publishing Press, Taipei, 1994, p. 441-3

- ↑ Lung Ying-tai, dajiang dahai 1949, Commonwealth Publishing Press, Taipei, 2009, p.184

- ↑ Harry S.Truman, Memoirs, Vol. Two: Years of Trial and Hope, 1946–1953 (Great Britain 1956), p.66

- ↑ p23, U.S. Military and CIA Interventions Since World War II, William Blum, Zed Books 2004 London.

- ↑ Lilley, James R. China Hands: Nine Decades of Adventure, Espionage, and Diplomacy in Asia. ISBN 1-58648-136-3.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 60.2 Westad, Odd Arne. [2003] (2003). Decisive Encounters: The Chinese Civil War, 1946–1950. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-4484-X. p 192-193.

- ↑ Pomfret, John. Red Army Starved 150,000 Chinese Civilians, Books Says. Associated Press; The Seattle Times. 2009-10-02. URL:http://community.seattletimes.nwsource.com/archive/?date=19901122&slug=1105487. Accessed: 2009-10-02. (Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/5kEN5bTlE)

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 Elleman, Bruce A. Modern Chinese Warfare, 1795–1989. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-21473-4.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 63.2 Finkelstein, David Michael. Ryan, Mark A. McDevitt, Michael. [2003] (2003). Chinese Warfighting: The PLA Experience Since 1949. M.E. Sharpe. China. ISBN 0-7656-1088-4. p 63

- ↑ Andrew D. W. Forbes (1986). Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: a political history of Republican Sinkiang 1911-1949. Cambridge, England: CUP Archive. p. 215. ISBN 0-521-25514-7. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Andrew D. W. Forbes (1986). Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: a political history of Republican Sinkiang 1911-1949. Cambridge, England: CUP Archive. p. 225. ISBN 0-521-25514-7. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Hsiao-ting Lin (2010). Modern China's ethnic frontiers: a journey to the west. Volume 67 of Routledge studies in the modern history of Asia (illustrated ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 117. ISBN 0-415-58264-4. Retrieved 2011-12-27.

China's far northwest.23 A simultaneous proposal suggested that, with the support of the new Panchen Lama and his entourage, at least three army divisions of the anti-Communist Khampa Tibetans could be mustered in southwest China.

- ↑ Hsiao-ting Lin (2010). Modern China's ethnic frontiers: a journey to the west. Volume 67 of Routledge studies in the modern history of Asia (illustrated ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. xxi. ISBN 0-415-58264-4. Retrieved 2011-12-27.

(tusi) from the Sichuan-Qinghai border; and Su Yonghe, a Khampa native-chieftan from Nagchuka on the Qinghai- Tibetan border. According to Nationalist intelligence reports, these leaders altogether commanded about 80000 irregulars.

- ↑ Cook, Chris Cook. Stevenson, John. [2005] (2005). The Routledge Companion to World History Since 1914. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-34584-7. p 376.

- ↑ Qi, Bangyuan. Wang, Dewei. Wang, David Der-wei. [2003] (2003). The Last of the Whampoa Breed: Stories of the Chinese Diaspora. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-13002-3. pg 2

- ↑ MacFarquhar, Roderick. Fairbank, John K. Twitchett, Denis C. [1991] (1991). The Cambridge History of China. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-24337-8. pg 820.

- ↑ Bush, Richard C. [2005] (2005). Untying the Knot: Making Peace in the Taiwan Strait. Brookings Institution Press. ISBN 0-8157-1288-X.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 72.2 72.3 72.4 Tsang, Steve Yui-Sang Tsang. The Cold War's Odd Couple: The Unintended Partnership Between the Republic of China and the UK, 1950–1958. [2006] (2006). I.B. Tauris. ISBN 1-85043-842-0. p 155, p 115-120, p 139-145

- ↑ Alison Behnke (1 January 2007). Taiwan in Pictures. Twenty-First Century Books. ISBN 978-0-8225-7148-3.

- ↑ News.bbc.co.uk

See also

External links

- Chronology of Civil War in China

- "Armored Car Like Oil Tanker Used by Chinese" Popular Mechanics, March 1930 article and photo of armoured train of Chinese Civil War

- THE CONCEPT OF OPERATIONS FOR THE HUAI-HAI CAMPAIGN

- bjorge huai.pdf

- Chinese Civil War 1945–1950

- Postal Stamps of the Chinese Post-Civil War Era

- Topographic maps of China Series L500, U.S. Army Map Service, 1954-

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||