Chief Justice of the United States

| Chief Justice of the United States | |

|---|---|

| |

| Style |

Mr. Chief Justice (Informal) The Honorable (Formal) Your Honor (When addressed directly in court) |

| Appointer | Presidential nomination with Senate confirmation |

| Term length | Life tenure |

| Inaugural holder |

as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court September 26, 1789 |

| Formation |

U.S. Constitution March 4, 1789 |

|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of the United States |

|

Executive

|

|

Politics portal |

The Chief Justice of the United States is the head of the United States federal court system (the judicial branch of the federal government of the United States) and the chief judge of the Supreme Court of the United States. The Chief Justice is one of nine Supreme Court justices; the other eight are the Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States. From 1789 until 1866, the office was known as the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court.

The Chief Justice is the highest judicial officer in the country, and acts as a chief administrative officer for the federal courts and as head of the Judicial Conference of the United States appoints the director of the Administrative Office of the United States Courts. The Chief Justice also serves as a spokesperson for the judicial branch.

The Chief Justice leads the business of the Supreme Court and presides over oral arguments before the court. When the court renders an opinion, the Chief Justice—when in the majority—decides who writes the court's opinion. The Chief Justice also has significant agenda-setting power over the court's meetings. In the case of an impeachment of a President of the United States, which has occurred twice, the Chief Justice presides over the trial in the Senate. In modern tradition, the Chief Justice has the ceremonial duty of administering the oath of office of the President of the United States.

The first Chief Justice was John Jay. The 17th and current Chief Justice is John G. Roberts, Jr.

Origin, title, and appointment to the post

The United States Constitution does not explicitly establish the office of Chief Justice, but presupposes its existence with a single reference in Article I, Section 3, Clause 6: "When the President of the United States is tried, the Chief Justice shall preside." Nothing more is said in the Constitution regarding the office, including any distinction between the Chief Justice and Associate Justices of the Supreme Court, who are not mentioned in the Constitution.

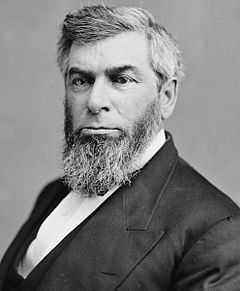

The office was originally known as "Chief Justice of the Supreme Court" and is still informally referred to using that title. However, 28 U.S.C. § 1 specifies that the title is "Chief Justice of the United States". The title was changed from Chief Justice of the Supreme Court by Congress in 1866 at the suggestion of the sixth Chief Justice, Salmon P. Chase.[1] Chase wished to emphasize the Supreme Court's role as a co-equal branch of government. The first Chief Justice commissioned using the new title was Melville Fuller in 1888.[1] Use of the previous title when referring to Chief Justices John Jay through Roger B. Taney is technically correct, as that was the legal title during their time on the court, but the newer title is frequently used retroactively for all Chief Justices.

The other eight members of the court are officially Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States, not "Associate Justices of the United States." The Chief Justice is the only member of the court to whom the Constitution refers as a "Justice," and only in Article I. Article III of the Constitution refers to all members of the Supreme Court (and of other federal courts) simply as "Judges."

The Chief Justice is nominated by the President of the United States and confirmed to sit on the Court by the United States Senate. The U.S. Constitution states that all justices of the court "shall hold their offices during good behavior," meaning that the appointments end only when a justice dies in office, resigns, or is impeached by the United States House of Representatives and convicted at trial by the Senate. The salary of the Chief Justice is set by Congress; the Constitution prohibits Congress from lowering the salary of any judge, including the Chief Justice, while that judge holds his or her office. As of 2015, the salary is $258,100 per year, which is slightly higher than that of the Associate Justices, which is $246,800. [2]

While the Chief Justice is appointed by the President, there is no specific constitutional prohibition against using another method to select the Chief Justice from among those Justices properly appointed and confirmed to the Supreme Court, and at least one scholar has proposed that presidential appointment should be done away with, and replaced by a process that permits the Justices to select their own Chief Justice.[3]

Three serving Associate Justices have received promotions to Chief Justice: Edward Douglass White in 1910, Harlan Fiske Stone in 1941, and William Rehnquist in 1986. Associate Justice Abe Fortas was nominated to the position of Chief Justice of the United States, but his nomination was filibustered by Senate Republicans in 1968. Despite the failed nomination, Fortas remained an Associate Justice until his resignation the following year. Most Chief Justices, including John Roberts, have been nominated to the highest position on the Court without any previous experience on the Supreme Court; indeed some, such as Earl Warren, received confirmation despite having no prior judicial experience.

There have been 21 individuals nominated for Chief Justice, of whom 17 have been confirmed by the Senate, although a different 17 have served. The second Chief Justice, John Rutledge, served in 1795 on a recess appointment, but did not receive Senate confirmation. Associate Justice William Cushing received nomination and confirmation as Chief Justice in January 1796, but declined the office; President Washington then nominated, and the Senate confirmed, Oliver Ellsworth, who served instead. The Senate subsequently confirmed President Adams's nomination of John Jay to replace Ellsworth, but Jay declined to resume his former office, citing the burden of riding circuit and its impact on his health, and his perception of the Court's lack of prestige. Adams then nominated John Marshall, whom the Senate confirmed shortly afterward.

When the Chief Justice dies in office or is otherwise unwilling or unable to serve, the duties of the Chief Justice temporarily are performed by the most senior sitting associate justice, who acts as Chief Justice until a new Chief Justice is confirmed.[3][4] Currently, Antonin Scalia is the most senior associate justice.

Duties

Along with the duties of the associate justices, the Chief Justice has several unique duties.

Impeachment trials

Article I, section 3 of the U.S. Constitution stipulates that the Chief Justice shall preside over impeachment trials of the President of the United States in the U.S. Senate. Two Chief Justices, Salmon P. Chase and William Rehnquist, have presided over the trial in the Senate that follows an impeachment of the president – Chase in 1868 over the proceedings against President Andrew Johnson and Rehnquist in 1999 over the proceedings against President Bill Clinton. Both presidents were subsequently acquitted.

Seniority

The Chief Justice is considered to be the justice with most seniority, independent of the number of years of service in the Supreme Court. As a result, the Chief Justice chairs the conferences where cases are discussed and voted on by the justices. The Chief Justice normally speaks first, and so has influence in framing the discussion.

The Chief Justice sets the agenda for the weekly meetings where the justices review the petitions for certiorari, to decide whether to hear or deny each case. The Supreme Court agrees to hear less than one percent of the cases petitioned to it. While associate justices may append items to the weekly agenda, in practice this initial agenda-setting power of the Chief Justice has significant influence over the direction of the court.

Despite the seniority and added prestige, the Chief Justice's vote carries the same legal weight as each of the other eight justices. In any decision, he has no legal authority to overrule the verdicts or interpretations of the other eight judges or tamper with them. However, in any vote, the most senior justice in the majority decides who will write the Opinion of the Court. This power to determine the opinion author (including the option to select oneself) allows a Chief Justice in the majority to influence the historical record. Two justices in the same majority, given the opportunity, might write very different majority opinions (as evidenced by many concurring opinions); being assigned the opinion may also cement the vote of an associate who is viewed as only marginally in the majority (a tactic that was reportedly used to some effect by Earl Warren). A Chief Justice who knows the associate justices can therefore do much—by the simple act of selecting the justice who writes the opinion of the court—to affect the "flavor" of the opinion, which in turn can affect the interpretation of that opinion in cases before lower courts in the years to come. It is said that some Chief Justices, notably Earl Warren and Warren E. Burger, sometimes switched votes to a majority they disagreed with to be able to use this prerogative of the Chief Justice to dictate who would write the opinion.[5]

Oath of office

The Chief Justice typically administers the oath of office at the inauguration of the President of the United States. This is a traditional rather than constitutional responsibility of the Chief Justice; the Constitution does not require that the oath be administered by anyone in particular, simply that it be taken by the president. Law empowers any federal and state judge, as well as notaries public, to administer oaths and affirmations.

If the Chief Justice is ill or incapacitated, the oath is usually administered by the next senior member of the Supreme Court. Seven times, someone other than the Chief Justice of the United States administered the oath of office to the President.[6] Robert Livingston, as Chancellor of the State of New York (the state's highest ranking judicial office), administered the oath of office to George Washington at his first inauguration; there was no Chief Justice of the United States, nor any other federal judge prior to their appointments by President Washington in the months following his inauguration. William Cushing, an associate justice of the Supreme Court, administered Washington's second oath of office in 1793. Calvin Coolidge's father, a notary public, administered the oath to his son after the death of Warren Harding.[7] This, however, was contested upon Coolidge's return to Washington and his oath was re-administered by Judge Adolph A. Hoehling, Jr. of the District of Columbia Supreme Court.[8] John Tyler and Millard Fillmore were both sworn in on the death of their predecessors by Chief Justice William Cranch of the Circuit Court of the District of Columbia.[9] Chester A. Arthur and Theodore Roosevelt's initial oaths reflected the unexpected nature of their taking office. On November 22, 1963, after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, Judge Sarah T. Hughes, a federal district court judge of the United States District Court for the Northern District of Texas, administered the oath of office to then Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson aboard the presidential airplane.

In addition, the Chief Justice ordinarily administers the oath of office to newly appointed and confirmed associate justices, whereas the senior associate justice will normally swear in a new Chief Justice or vice president.

Other duties

The Chief Justice also:

- Serves as the head of the federal judiciary.

- Serves as the head of the Judicial Conference of the United States, the chief administrative body of the United States federal courts. The Judicial Conference is empowered by the Rules Enabling Act to propose rules, which are then promulgated by the Supreme Court subject to a veto by Congress, to ensure the smooth operation of the federal courts. Major portions of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure and Federal Rules of Evidence have been adopted by most state legislatures and are considered canonical by American law schools.

- Appoints sitting federal judges to the membership of the United States Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC), a "secret court" which oversees requests for surveillance warrants by federal police agencies (primarily the F.B.I.) against suspected foreign intelligence agents inside the United States. (see 50 U.S.C. § 1803).

- Appoints the members of the Judicial Panel on Multidistrict Litigation, a special tribunal of seven sitting federal judges responsible for selecting the venue for coordinated pretrial proceedings in situations where multiple related federal actions have been filed in different judicial districts.

- Serves ex officio as a member of the Board of Regents, and by custom as the Chancellor, of the Smithsonian Institution.

- Supervises the acquisition of books for the Law Library of the Library of Congress.[10]

Unlike Senators and Representatives who are constitutionally prohibited from holding any other "office of trust or profit" of the United States or of any state while holding their congressional seats, the Chief Justice and the other members of the federal judiciary are not barred from serving in other positions. Chief Justice John Jay served as a diplomat to negotiate the so-called Jay Treaty (also known as the Treaty of London of 1794), and Chief Justice Earl Warren chaired The President's Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy. As described above, the Chief Justice holds office in the Smithsonian Institution and the Library of Congress.

Disability or vacancy

Under 28 USC 3, when the Chief Justice is unable to discharge his functions, or that office is vacant, his duties are carried out by the most senior associate justice who is able to act, until the disability or vacancy ends.

List of Chief Justices

| No. | Name | Image | Nominated | Vote | Term start (oath) | Term end | Length of term | Length of retirement | Date of death | President |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | John Jay |  |

September 24, 1789 | September 26, 1789 | October 19, 1789 | June 29, 1795 | 2,079 days | 12,375 days | May 17, 1829 | Washington |

| 2 | John Rutledge §, ¤ |  |

July 1, 1795 | December 15, 1795 | August 12, 1795 | December 28, 1795 | 125 days | 1,649 days | June 21, 1800 | Washington |

| 3 | Oliver Ellsworth |  |

March 3, 1796 | March 4, 1796 | March 8, 1796 | December 15, 1800 | 1,742 days | 2,537 days | November 26, 1807 | Washington |

| 4 | John Marshall |  |

January 20, 1801 | January 27, 1801 | February 4, 1801 | July 6, 1835† | 12,570 days | N/A[11] | July 6, 1835 | J. Adams (F) |

| 5 | Roger B. Taney |  |

December 28, 1835 | March 15, 1836 | March 28, 1836 | October 12, 1864† | 10,425 days | N/A[11] | October 12, 1864 | Jackson (D) |

| 6 | Salmon P. Chase | .jpg) |

December 6, 1864 | December 6, 1864 | December 15, 1864 | May 7, 1873† | 3,074 days | N/A[11] | May 7, 1873 | Lincoln (R) |

| 7 | Morrison Waite |  |

January 19, 1874 | January 21, 1874 | March 4, 1874 | March 23, 1888† | 5,133 days | N/A[11] | March 23, 1888 | Grant (R) |

| 8 | Melville Fuller |  |

April 30, 1888 | July 20, 1888 | October 8, 1888 | July 4, 1910† | 7,938 days | N/A[11] | July 4, 1910 | Cleveland (D) |

| 9 | Edward Douglass White ° |  |

December 12, 1910 | December 12, 1910 | December 19, 1910 | May 19, 1921† | 3,804 days | N/A[11] | May 19, 1921 | Taft (R) |

| 10 | William Howard Taft ♦ |  |

June 30, 1921 | June 30, 1921 | July 11, 1921 | February 3, 1930 | 3,129 days | 33 days | March 8, 1930 | Harding (R) |

| 11 | Charles Evans Hughes ¤ |  |

February 3, 1930 | February 13, 1930 | February 24, 1930 | July 1, 1941 | 4,144 days | 2,615 days | August 27, 1948 | Hoover (R) |

| 12 | Harlan F. Stone ° |  |

June 12, 1941 | June 27, 1941 | July 3, 1941 | April 22, 1946† | 1,754 days | N/A[11] | April 22, 1946 | F. D. Roosevelt (D) |

| 13 | Fred M. Vinson |  |

June 6, 1946 | June 20, 1946 | June 24, 1946 | September 8, 1953† | 2,633 days | N/A[11] | September 8, 1953 | Truman (D) |

| 14 | Earl Warren |  |

January 11, 1954 | March 1, 1954 | October 5, 1953[12] | June 23, 1969 | 5,740 days | 1,842 days | July 9, 1974 | Eisenhower (R) |

| 15 | Warren E. Burger |  |

May 21, 1969 | June 9, 1969 | June 23, 1969 | September 26, 1986 | 6,304 days | 3,194 days | June 25, 1995 | Nixon (R) |

| 16 | William Rehnquist ° |  |

June 17, 1986 | September 17, 1986 | September 26, 1986 | September 3, 2005† | 6,917 days | N/A[11] | September 3, 2005 | Reagan (R) |

| 17 | John G. Roberts, Jr. |  |

September 6, 2005 | September 29, 2005 | September 29, 2005 | present | 3,500 days | Incumbent | G. W. Bush (R) |

- § Recess appointment, later rejected by the Senate on December 15, 1795

- ¤ Previously served as an Associate Justice, but at a time disconnected to service as Chief Justice

- ° Elevated from Associate Justice

- ♦ Previous service as President of the United States

- † Died in office

Data based on:

- The Oxford Guide to United States Supreme Court Decisions, Kermit L. Hall, 1999, Oxford University Press

- https://www.senate.gov/pagelayout/reference/nominations/Nominations.htm

- http://www.supremecourt.gov/about/members_text.aspx

See also

- List of Chief Justices of the United States by time in office

- Lists of United States Supreme Court cases

Notes and references

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "History of the Federal Judiciary". Fjc.gov. Retrieved 2011-08-17.

- ↑ http://www.uscourts.gov/JudgesAndJudgeships/JudicialCompensation/judicial-salaries-since-1968.aspx

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Pettys, Todd E. (2006). "Choosing a Chief Justice: Presidential Prerogative or a Job for the Court?". Journal of Law & Politics 22: 231.

- ↑ 28 U.S.C. §§3-4.

- ↑ See for example the description of the behind-the-scenes maneuvering after Roe v. Wade was argued the first time, in Bob Woodward and Scott Armstrong's The Brethren.

- ↑ Library of Congress. "Presidential Inaugurations: Presidential Oaths of Office."

- ↑ "Excerpt from Coolidge's autobiography". Historicvermont.org. Retrieved 2010-05-15.

- ↑ "Prologue: Selected Articles". Archives.gov. Retrieved 2010-05-15.

- ↑ "Presidential Swearing-In Ceremony, Part 5 of 6". Inaugural.senate.gov. Retrieved 2011-08-17.

- ↑ "Jefferson's Legacy: A Brief History of the Library of Congress". Library of Congress. 2006-03-06. Retrieved 2008-01-14.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 11.8 Died while in office.

- ↑ Warren was placed on the Court by recess appointment; he was formally nominated and confirmed afterwards, and was sworn in on March 2, 1954

Further reading

- Abraham, Henry J. (1992). Justices and Presidents: A Political History of Appointments to the Supreme Court (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-506557-3.

- Cushman, Clare (2001). The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies, 1789–1995 (2nd ed.). (Supreme Court Historical Society, Congressional Quarterly Books). ISBN 1-56802-126-7.

- Flanders, Henry. The Lives and Times of the Chief Justices of the United States Supreme Court. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co., 1874 at Google Books.

- Frank, John P. (1995). Friedman, Leon; Israel, Fred L., eds. The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions. Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 0-7910-1377-4.

- Hall, Kermit L., ed. (1992). The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505835-6.

- Martin, Fenton S.; Goehlert, Robert U. (1990). The U.S. Supreme Court: A Bibliography. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Quarterly Books. ISBN 0-87187-554-3.

- Urofsky, Melvin I. (1994). The Supreme Court Justices: A Biographical Dictionary. New York: Garland Publishing. p. 590. ISBN 0-8153-1176-1.

External links

Media related to Chief Justice of the United States at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Chief Justice of the United States at Wikimedia Commons

| ||||||||

| ||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.jpg)