Chicago Pile-1

|

Site of the First Self Sustaining Nuclear Reaction | |

|

Chicago Landmark | |

| |

|

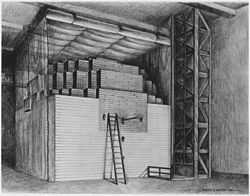

Drawing of the reactor | |

| |

| Location | Chicago, Cook County, Illinois, USA |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 41°47′32″N 87°36′3″W / 41.79222°N 87.60083°WCoordinates: 41°47′32″N 87°36′3″W / 41.79222°N 87.60083°W |

| Built | 1942[1] |

| Governing body | Regenstein Library |

| NRHP Reference # | 66000314[2] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966 66000314[2] |

| Designated NHL | February 18, 1965[1] |

| Designated CL | October 27, 1971[3] |

| Chicago Pile-1 (CP-1) | |

|---|---|

| Reactor concept | Research reactor (uranium/graphite) |

| Designed and build by | Metallurgical Laboratory |

| Operational | 1942 to 1943 |

| Status | Dismantled |

| Main parameters of the reactor core | |

| Fuel (fissile material) | 235U |

| Fuel state | Solid (pellets) |

| Neutron energy spectrum | Information missing |

| Primary control method | Control rods |

| Primary moderator | Graphite (bricks) |

| Primary coolant | None |

| Reactor usage | |

| Primary use | Experimental |

| Remarks | The Chicago Pile-1 (CP-1) was the world's first artificial nuclear reactor. |

Chicago Pile-1 (CP-1) was the world's first artificial nuclear reactor.[4][5] The construction of CP-1 was part of the Manhattan Project, and was carried out by the Metallurgical Laboratory at the University of Chicago. It was built under the west viewing stands of the original Stagg Field. The first man-made self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction was initiated in CP-1 on 2 December 1942, under the supervision of Enrico Fermi. Fermi described the apparatus as "a crude pile of black bricks and wooden timbers." It was made of a large amount of graphite and uranium, with "control rods" of cadmium, indium, and silver, and unlike most subsequent reactors, it had no radiation shield or cooling system.

The site is now a National Historic Landmark and a Chicago Landmark.

Reactor

The reactor was a "pile" of uranium pellets and graphite blocks, assembled under the supervision of the renowned physicist Enrico Fermi, in collaboration with Leó Szilárd, discoverer of the chain reaction, and assisted by Martin Whitaker, Walter Zinn, and George Weil. It contained a critical mass of fissile material (when moderated by the graphite), together with control rods. The shape of the pile was intended to be roughly spherical, but as work proceeded Fermi calculated that critical mass could be achieved without finishing the entire pile as planned.[6]

CP-1 was originally to be built in Red Gate Woods, a forest preserve outside the city, but a labor strike prevented this. So Fermi built the "pile" under the west stands of Stagg Field, the University's abandoned football stadium, in a space that had been used as a rackets court.[7] In the pile, the neutron-producing uranium pellets were separated from one another by graphite blocks. Some of the free neutrons produced by the natural decay of uranium would be absorbed by other uranium atoms, causing nuclear fission of those atoms and the release of additional free neutrons. The graphite between the uranium pellets was a neutron moderator; it slowed the neutrons, increasing the chance they would be absorbed.

The controls were rods made of cadmium, indium, and silver. Cadmium and indium absorb neutrons; silver becomes radioactive when irradiated by neutrons, which is used for measuring their flux. When the rods were inserted into the pile, the cadmium absorbed free neutrons, preventing the chain reaction. As the rods were withdrawn, more neutrons would strike uranium atoms, until a self-sustaining chain reaction developed. Re-inserting the rods would dampen the reaction.

The pile required an enormous amount of graphite and uranium. At the time, there was a limited source of pure uranium. Frank Spedding of Iowa State University was able to produce only two short tons of pure uranium. Westinghouse Lamp Plant supplied another three short tons of uranium metal, which it produced in a rush with a makeshift process. A large square balloon was constructed by Goodyear Tire to encase the pile.[8][9]

First nuclear chain reaction

On 2 December 1942, CP-1 was ready for a demonstration. Before a group of dignitaries, George Weil worked the final control rod while Fermi carefully monitored the neutron activity. The pile "went critical" (reached a self-sustaining reaction) at 15:25. Fermi shut it down 28 minutes later.

After the chain reaction was observed, Arthur Compton, head of the Metallurgical Laboratory, notified James Conant, chairman of the National Defense Research Committee, by telephone. The conversation was in an impromptu code:

- Compton: The Italian navigator has landed in the New World.

- Conant: How were the natives?

- Compton: Very friendly.[10]

Unlike most reactors that have been built since, CP-1 had no radiation shielding and no cooling system of any kind. Fermi had convinced Arthur Compton that his calculations were reliable enough to rule out a runaway chain reaction or an explosion. But, as the official historians of the Atomic Energy Commission later noted, the "gamble" remained in conducting "a possibly catastrophic experiment in one of the most densely populated areas of the nation!"[11]

Later operation

Operation of CP-1 was terminated in February 1943. The pile was then dismantled and moved to Red Gate Woods. There it was reconstructed using the original materials, plus an enlarged radiation shield, and renamed Chicago Pile-2 (CP-2). CP-2 began operation in March 1943 and was later buried at the same site, now known as the Site A/Plot M Disposal Site. CP-2 and other activities at the Red Gate Woods site led to it becoming the first site of Argonne National Laboratory.[6]

Significance and commemoration

The site of CP-1 was designated as a National Historic Landmark on 18 February 1965.[1] When the National Register of Historic Places was created in 1966, it was immediately added to that as well.[2] The site was named a Chicago Landmark on 27 October 1971.[3] It is one of the four Registered Chicago Historic Places on the initial National Register.

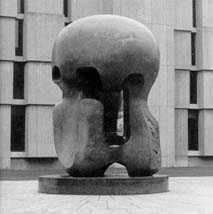

The site of the old Stagg Field is now occupied by the University's Regenstein Library. A Henry Moore sculpture, Nuclear Energy, stands in a small quadrangle just outside the Library, to commemorate the nuclear experiment.[1]

A small graphite block from CP-1 can be seen at the Bradbury Science Museum in Los Alamos, New Mexico; another is currently on display at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago.

See also

- F-1 (nuclear reactor), its Soviet equivalent, built in 1946 and still operational

- ZEEP, its Canadian equivalent.

- Chicago Pile-3

- Chicago Pile-5

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 "Site of the First Self-Sustaining Nuclear Reaction". National Historic Landmark Summary Listing. National Park Service. Retrieved 2013-07-26.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. 2010-07-09.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Site of the First Self-Sustaining Controlled Nuclear Chain Reaction". City of Chicago. Retrieved 2013-07-26.

- ↑ "Reactors Designed by Argonne National Laboratory: Chicago Pile 1". Argonne National Laboratory. 21 May 2013. Retrieved 2013-07-26.

- ↑ "Atoms Forge a Scientific Revolution". Argonne National Laboratory. 10 July 2012. Retrieved 2013-07-26.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Fermi, E. (1946). "The Development of the first chain reaction pile". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 90: 20–24. JSTOR 3301034.

- ↑ Zug, J. (2003). Squash, A History of the Game. Scribner. pp. 135–136. ISBN 978-0-7432-2990-6. The space is commonly misidentified as having been a squash court.

- ↑ "FRONTIERS Research Highlights 1946-1996". Argonne National Laboratory. 1996. p. 11. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- ↑ Walsh, J. (1981). "A Manhattan Project Postscript". Science 212 (4501): 1369–1371. Bibcode:1981Sci...212.1369W. doi:10.1126/science.212.4501.1369. PMID 17746246.

- ↑ "Argonne's Nuclear Science and Technology Legacy: The Italian Navigator Lands". Argonne National Laboratory. 10 July 2012. Retrieved 2013-07-26.

- ↑ "CP-1 GOES CRITICAL". The Manhattan Project An Interactive History. U.S. Department of Energy. 2 December 1942. Archived from the original on 2010-11-22.

External links

- CP-1 Goes Critical Describes in detail the construction and activation of CP-1. US Department of Energy, Office of History and Heritage Resources.

- Photos of CP-1 The University of Chicago Library Archive. Includes photos and sketches of CP-1.

- Video Showing the Met Lab, Fermi, and an active experiment using CP-1

- The First Pile 11 page story about CP-1

- History of Nuclear Proliferation For more on the history of nuclear proliferation see the Woodrow Wilson Center's Nuclear Proliferation International History Project website.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||