Chiastic structure

Chiastic structure, or chiastic pattern, is a literary technique in narrative motifs and other textual passages. An example chiastic structure would be two ideas, A and B, together with variants A' and B', being presented as A,B,B',A'. Alternative names include ring structure, because the opening and closing 'A' can be viewed as completing a circle, palistrophe,[1] or symmetric structure. It may be regarded as chiasmus scaled up from clauses to larger units of text.

These often symmetrical patterns are commonly found in ancient literature such as the epic poetry of the Odyssey and the Iliad. Various chiastic structures are also seen in the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament, where biblical writers used it to illustrate or highlight details of particular importance.

Etymology

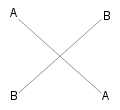

The term chiastic derives from the mid-17th century term chiasmus, which refers to a crosswise arrangement of concepts or words that are repeated in reverse order. Chiasmus derives from the Greek word khiasmos, a word that is khiazein, marked with the letter khi. From khi comes chi.[2]

Chi is made up of two lines crossing each other as in the shape of an X. The line that starts leftmost on top, comes down, and is rightmost on the bottom, and vice versa. If one thinks of the lines as concepts, one sees that concept A, which comes first, is also last, and concept B, which comes after A, comes before A. If one adds in more lines representing other concepts, one gets a chiastic structure with more concepts. See Proverbs 1:20-33; vs 20-21=A, v 22=B, v 23=C, vs 24-25=D, vs 26-28=E, vs 29-30=D', v 31=C', v 32=B', v 33=A' [3]

Mnemonic device

Oral literature is especially rich in chiastic structure, possibly as an aid to memorization. In his study of the Iliad and the Odyssey, Cedric Whitman, for instance, finds a chiastic structure "of the most amazing virtuosity" that simultaneously performed both aesthetic and mnemonic functions, permitting the oral poet to easily recall the basic formulae of the composition during performances.[4]

Use in Hebrew Bible

A notable example in the Torah is the chiastic structure running from the middle of Exodus through the end of Leviticus. The structure begins with the covenant made between God and the Hebrew People at Mount Sinai, as described in the Torah, and ends with the admonition from God (YHWH) to the Hebrews of what will happen if they will not follow his laws, which is also a sort of covenant. The main ideas are in the middle of Leviticus, from chapter 11 through chapter 20. Those chapters deal with the holiness in the Tabernacle and the holiness of the Israelite people in general. The chiastic structure points the reader to the central idea, that of the expected holiness (set-apartness) of the Israelite people in everything they do. In David Dorsey's book and in his teaching, he poses that the chiastic structure provides a form of interpretive control by the authors of the various books in the Hebrew Scriptures.

Book of Genesis

In the Book of Genesis, the beginning of chapter 4 uses the ABBAABB…ABBA chiastic structure. This structure is used to contrast concepts A and B, which are usually closely related, but very different. First, concept A is mentioned once. Then B twice, A twice, etc., until the structure ends with a final A. The format points the contrast between the two ideas.

The ABBAABB…ABBA pattern emphasizes the contrast between the two sons of Adam, Cain and Abel. The Torah describes their names, their occupations, and their offerings. Cain is mentioned first, then Abel twice, then Cain twice, and so on. The structure draws attention to the differences between Cain and Abel, pointing out the essential difference in their personalities. Similarly the ABCDEDCBA pattern is used in Genesis 11 vs 1-9 to emphasize the presence of the Lord in Babel.

Book of Daniel

In 1986, William H. Shea proposed that the Book of Daniel is composed of a double-chiasm. He argued that the chiastic structure is emphasized by the two languages that the book is written in: Aramaic and Hebrew. The first chiasm is written in Aramaic from chapters 2-7 following an ABC...CBA pattern. The second chiasm is in Hebrew from chapters 8-12, also using the ABC...CBA pattern. However, Shea represents Daniel 9:26 as "D", a break in the center of the pattern.[5]

Use in the Qurʾān

The themes in the Pedestal Verse and the story of Joseph are presented in a chiastic structure. Several other passages exist in a type of ring symmetry, or symmetrical structure.[6]

ABC…CBA pattern

The ABC…CBA chiastic structure is frequently used to emphasize the innermost concept, i.e., C, the concept that appears either twice in succession or only once, showing that the other ideas all lead up to the middle idea or concept.

Beowulf

In literary texts with a possible oral origin, such as Beowulf, chiastic or ring structures are often found on an intermediate level, that is, between the (verbal and/or grammatical) level of chiasmus and the higher level of chiastic structure such as noted in the Torah. John D. Niles provides examples of chiastic figures on all three levels.[7] He notes that for the instances of ll. 12-19, the announcement of the birth of (Danish) Beowulf, are chiastic, more or less on the verbal level, that of chiasmus.[8] Then, each of the three main fights are organized chiastically, a chiastic structure on the level of verse paragraphs and shorter passages. For instance, the simplest of these three, the fight with Grendel, is schematized as follows:

A: Preliminaries

- Grendel approaching

- Grendel rejoicing

- Grendel devouring Handscioh

- B: Grendel's wish to flee ("fingers cracked")

- C: Uproar in hall; Danes stricken with terror

- HEOROT IN DANGER OF FALLING

- C': Uproar in hall; Danes stricken with terror

- C: Uproar in hall; Danes stricken with terror

- B': "Joints burst"; Grendel forced to flee

A': Aftermath

- Grendel slinking back toward fens

- Beowulf rejoicing

- Beowulf left with Grendel's arm[9]

Finally, Niles provides a diagram of the highest level of chiastic structure, the organization of the poem as a whole, in an introduction, three major fights with interludes before and after the second fight (with Grendel's mother), and an epilogue. To illustrate, he analyzes Prologue and Epilogue as follows:

Prologue

A: Panegyric for Scyld

- B: Scyld's funeral

- C: History of Danes before Hrothgar

- D: Hrothgar's order to build Heorot

- C: History of Danes before Hrothgar

Epilogue

- D': Beowulf's order to build his barrow

- C': History of Geats after Beowulf ("messenger's prophecy")

- B': Beowulf's funeral

A': Eulogy for Beowulf[10]

Paradise Lost

The overall chiastic structure of Milton's Paradise Lost is also of the ABC…CBA type:

A: Satan's sinful actions (Books 1-3)

- B: Entry into Paradise (Book 4)

- C: War in heaven (destruction) (Books 5-6)

- C': Creation of the world (Books 7-8)

- B': Loss of paradise (Book 9)

A': Humankind's sinful actions (Books 10-12)[11]:141

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ The term "palistrophe" was coined in: McEvenue, Sean E. (1971), The Narrative Style of the Priestly Writer, Rome: Biblical Institute Press, OCLC 292126.

- ↑ "US English dictionary", OxfordDictionaries.com (Oxford University Press), retrieved 2014-07-10

|chapter=ignored (help) - ↑ Garrett 1993, p. 71

- ↑ Whitman, Cedric M. (1958), Homer and the Heroic Tradition, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, OCLC 310021.

- ↑ Shea 1986

- ↑ "Author Interview: How to Read the Qur'an by Carl W. Ernst", uncpress.unc.edu (University of North Carolina Press), 2011

- ↑ Niles 1979, pp. 924–35

- ↑ Niles 1979, pp. 924–25

- ↑ Niles 1979, pp. 925–6

- ↑ Niles 1979, p. 930

- ↑ Ryken, Leland (2004). "Paradise Lost by John Milton (1608-1674)". In Kapic, Kelly M.; Gleason, Randall C. The Devoted Life: An Invitation to the Puritan Classics. Downers Grove, Illinois: Inter-Varsity Press. pp. 138–151. ISBN 0-8308-2794-3. OCLC 55495010.

References

- Garrett, Duane A. (1993). Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of songs. The New American Commentary, v. 14. Nashville, Tennessee: Broadman Press. ISBN 0-8054-0114-8. OCLC 27895425.

- Niles, John D. (1979). "Ring Composition and the Structure of Beowulf". PMLA (Modern Language Association) 94 (5): 924–35. doi:10.2307/461974. JSTOR 461974.

- Shea, William H. (1986). "The Prophecy of Daniel 9:24-27". In Holbrook, Frank. The Seventy Weeks, Leviticus, and the Nature of Prophecy. Daniel and Revelation Committee Series 3. Washington, D.C.: Biblical Research Institute, General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists. OCLC 14279279.

Further reading

- Breck, John (1994). The Shape of Biblical Language: Chiasmus in the Scriptures and Beyond. Crestwood, N.Y.: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 978-0-8814-1139-3. OCLC 30893460.

- Dorsey, David A. (1999), The Literary Structure of the Old Testament: A Commentary on Genesis-Malachi, Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, ISBN 0801021871, OCLC 42002627

- Ehrman, Bart D. (1993), The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture: the effect of early Christological controversies on the text of the New Testament, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0195080785, OCLC 26354078

- Lund, Nils Wilhelm (1942), Chiasmus in the New Testament, a study in formgeschichte, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, OCLC 2516087

- McCoy, Brad (Fall 2003), "Chiasmus: An Important Structural Device Commonly Found in Biblical Literature", CTS Journal (Albuquerque, New Mexico: Chafer Theological Seminary) 9 (2): 18–34

- Parry, Donald W. (2007) [1998], Poetic Parallelisms in the Book of Mormon (Revised ed.), Provo, Utah: Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, ISBN 978-0-934893-36-7

- Prewitt, Terry J. (1990), The Elusive Covenant: A Structural-Semiotic Reading of Genesis, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, ISBN 0253345995, OCLC 20827915

- Ramirez, Matthew Eric (January 2011). "Descanting on Deformity: The Irregularities in Shakespeare's Large Chiasms". Text and Performance Quarterly 31 (1): 37–49. doi:10.1080/10462937.2010.526240.

- Welch, John W. (1995), "Criteria for Identifying and Evaluating the Presence of Chiasmus", Journal of Book of Mormon Studies (Brigham Young University) 4 (2)

- Welch, John W. (1999) [1981], Chiasmus in antiquity: structures, analyses, exegesis, Provo, Utah: Research Press, ISBN 0934893330, OCLC 40126818