Chestnut-banded plover

| Chestnut-banded plover | |

|---|---|

| |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Charadriiformes |

| Family: | Charadriidae |

| Genus: | Charadrius |

| Species: | C. pallidus |

| Binomial name | |

| Charadrius pallidus Strickland, 1852 | |

The chestnut-banded plover (Charadrius pallidus) is a species of bird in the Charadriidae family. This species has a large range, being distributed across Southern Africa. However, it actually occupies a rather small area.

Identification

It grows about 15 cm tall and has proportionally long dark legs, black lores and eye-stripes leading to a black bill. The forehead, throat and belly are white, while a chestnut breast-band joins a band of same colour on the fore-crown. Back and crown are greyish-brown.

Behaviour

Although this species' movements vary throughout its range and are therefore poorly understood it is thought to be a partial migrant.[2]

General Behaviour

The number of chestnut-banded plovers varies from year to year at any given site. Especially in response to droughts at inland breeding sites will the population fluctuate, reflecting even on the size of the global population. Breeding mostly coincides with rains. This bird can usually be found in pairs of small groups. Pairs defend territories particularly during the breeding season. During the non-breeding season, it forms very large communities. At one point, 375 birds were seen together in Namibia.[3] It is known to sometimes forage in loose flocks of up to 60 birds and will occasionally roost with other plover species.[4]

South Africa

Coastal Birds in South Africa appear to be mostly resident. They breed between March and May as well as from September to January.[5]

Namibia

In Namibia, some coastal birds move inland to breed while some inland birds join the coastal populations after their breeding. In years of drought, the birds remain at the coast.

It is not quite clear when the Namibian population breeds. Based on reports of birds moving inland from the coast during the rains in January, and being seen in large numbers during June and July, breeding season could be between January and June.[6]

However, the breeding months are placed between March and October according to some authors, who also report large numbers of the chestnut-banded plover at the coast during December and January.[7] or [8]

African Great Lakes

The plover populations in Kenya and Tanzania in the African Great Lakes breed between March and October.[9] The birds move up and down the Rift Valley, with peal numbers occurring at Lake Manyara between July and September. There are reports of birds outside their normal range, which suggests some kind of nomadism.[10]

Habitat

This species is mostly associated with alkaline and saline water.[11]

Distribution

Charadrius pallidus has two separate populations. The nominate subspecies is found in Angola, Botswana, Kenya, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe. The subspecies venustus can only be found in the Rift Valley in Kenya and Tanzania.

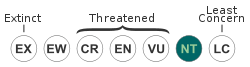

However, because it occurs at fewer than ten locations in the non-breeding season, and habitat quality thereof is declining, the chestnut-banded plover is evaluated as Near Threatened in the 2007 IUCN Red List.[12]

Population

The global population is estimated to be around 17,500 individuals. During non-breeding season, Walvis Bay and Sandwich Harbour in Namibia and Lake Natron in Tanzania can hold 87% of the world population.

Breeding Habitat

This species breeds in alkaline and saline wetlands, including inland salt pans. It will even make use of man-made salt ponds. At the coast, it is found around lagoons and salt marshes. Preferring areas devoid of vegetation, it is hardly found more than 50m from the water'S edge. The nest is a round scrape in calcareous soil, dry mud or stony ground. It usually has a diameter of 5 cm and is 1 cm deep.

Non-breeding Habitat

During non-breeding season, the chestnut-banded plover is increasingly found in its coastal habitat. It now occurs up to 1 km away from the water.

Diet

The exact diet is unknown but believed to consist of insect larvae and small crustaceans.[13]

Habitual Threats

Two key sites face ongoing threats by the human population.

Walvis Bay

Walvis Bay on Namibia's central coast, premier site for this species, faces pollution by Namibia's largest port and siltation by a salt works at the southern end of the lagoon. Pollution by the port includes concentrations of fish oils and other detritus from ships.[14]

Lake Natron

Despite its unwelcoming climate and inaccessibility, Lake Natron in Tanzania may suffer reduced water input in future, reducing the chestnut-banded plover's habitat greatly. An irrigation project on the Ewaso-Ngiro River and a soda-extraction plant along the lake's south-western shores threaten to use much of the water that would otherwise flow into the lake.[15]

Conservation

The three most important habitat sites are designated Ramsar sites and Important Bird Areas. Sandwich Harbour is additionally a National Park while Lake Natron is a game controlled area.

References

- ↑ BirdLife International (2012). "Charadrius pallidus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ↑ see del Hoyo, J.; Elliott, A.; Sargatal, J. 1996. Handbook of the Birds of the World, vol. 3: Hoatzin to Auks

- ↑ Hockey et al. 2005

- ↑ del Hoyo et al. 1996, Hockey et al. 2005

- ↑ see del Hoyo et al. 1996

- ↑ Simmons, R.E.; Brown, C.J. 2006. Birds to watch in Namibia: red, rare and endemic species. National Biodiversity Programme, Windhoek

- ↑ Hockey et al. 2005

- ↑ Whitelaw, D.A., Underhill, L.G., Cooper, J. & Clinning, C.F. 1978. Waders (Charadrii) and other birds on the Namib Coast: counts and conservation priorities

- ↑ del Hoyo et al. 1996

- ↑ Hocke et al. 2005

- ↑ Johnsgard, P. A. 1981. The plovers, sandpipers and snipes of the world University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, U.S.A. and London

- ↑ See BirdLife International (2007a. b).

- ↑ del Hoyo et al. 1996, Hockey et al. 2005

- ↑ Simmons et al. 2007

- ↑ Baker and Baker 2001

- BirdLife International (2007a): [ 2006-2007 Red List status changes ]. Retrieved 2007-AUG-26.

- BirdLife International (2007b): Chestnut-banded Plover - BirdLife Species Factsheet. Retrieved 2007-AUG-26.

External links

- Chestnut-banded plover - Species text in The Atlas of Southern African Birds.