Chern class

In mathematics, in particular in algebraic topology, differential geometry and algebraic geometry, the Chern classes are characteristic classes associated to complex vector bundles.

Chern classes were introduced by Shiing-Shen Chern (1946).

Geometric approach

Basic idea and motivation

Chern classes are characteristic classes. They are topological invariants associated to vector bundles on a smooth manifold. The question of whether two ostensibly different vector bundles are the same can be quite hard to answer. The Chern classes provide a simple test: if the Chern classes of a pair of vector bundles do not agree, then the vector bundles are different. The converse, however, is not true.

In topology, differential geometry, and algebraic geometry, it is often important to count how many linearly independent sections a vector bundle has. The Chern classes offer some information about this through, for instance, the Riemann-Roch theorem and the Atiyah-Singer index theorem.

Chern classes are also feasible to calculate in practice. In differential geometry (and some types of algebraic geometry), the Chern classes can be expressed as polynomials in the coefficients of the curvature form.

Construction of Chern classes

There are various ways of approaching the subject, each of which focuses on a slightly different flavor of Chern class.

The original approach to Chern classes was via algebraic topology: the Chern classes arise via homotopy theory which provides a mapping associated to V to a classifying space (an infinite Grassmannian in this case). Any vector bundle V over a manifold may be realized as the pullback of a universal bundle over the classifying space, and the Chern classes of V can therefore be defined as the pullback of the Chern classes of the universal bundle; these universal Chern classes in turn can be explicitly written down in terms of Schubert cycles.

Chern's approach used differential geometry, via the curvature approach described predominantly in this article. He showed that the earlier definition was in fact equivalent to his. The resulting theory is known as the Chern–Weil theory.

There is also an approach of Alexander Grothendieck showing that axiomatically one need only define the line bundle case.

Chern classes arise naturally in algebraic geometry. The generalized Chern classes in algebraic geometry can be defined for vector bundles (or more precisely, locally free sheaves) over any nonsingular variety. Algebro-geometric Chern classes do not require the underlying field to have any special properties. In particular, the vector bundles need not necessarily be complex.

Regardless of the particular paradigm, the intuitive meaning of the Chern class concerns 'required zeroes' of a section of a vector bundle: for example the theorem saying one can't comb a hairy ball flat (hairy ball theorem). Although that is strictly speaking a question about a real vector bundle (the "hairs" on a ball are actually copies of the real line), there are generalizations in which the hairs are complex (see the example of the complex hairy ball theorem below), or for 1-dimensional projective spaces over many other fields.

See Chern–Simons for more discussion.

The Chern class of line bundles

(Let X be a topological space having the homotopy type of a CW complex.)

An important special case occurs when V is a line bundle. Then the only nontrivial Chern class is the first Chern class, which is an element of the second cohomology group of X. As it is the top Chern class, it equals the Euler class of the bundle.

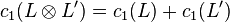

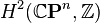

The first Chern class turns out to be a complete invariant with which to classify complex line bundles, topologically speaking. That is, there is a bijection between the isomorphism classes of line bundles over X and the elements of H2(X;Z), which associates to a line bundle its first Chern class. Moreover, this bijection is a group homomorphism (thus an isomorphism):

;

;

the tensor product of complex line bundles corresponds to the addition in the second cohomology group.[1][2]

In algebraic geometry, this classification of (isomorphism classes of) complex line bundles by the first Chern class is a crude approximation to the classification of (isomorphism classes of) holomorphic line bundles by linear equivalence classes of divisors.

For complex vector bundles of dimension greater than one, the Chern classes are not a complete invariant.

Constructions

Via the Chern–Weil theory

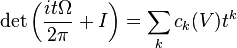

Given a complex hermitian vector bundle V of complex rank n over a smooth manifold M, a representative of each Chern class (also called a Chern form) ck(V) of V are given as the coefficients of the characteristic polynomial of the curvature form Ω of V.

The determinant is over the ring of n × n matrices whose entries are polynomials in t with coefficients in the commutative algebra of even complex differential forms on M. The curvature form Ω of V is defined as

with ω the connection form and d the exterior derivative, or via the same expression in which ω is a gauge form for the gauge group of V. The scalar t is used here only as an indeterminate to generate the sum from the determinant, and I denotes the n × n identity matrix.

To say that the expression given is a representative of the Chern class indicates that 'class' here means up to addition of an exact differential form. That is, Chern classes are cohomology classes in the sense of de Rham cohomology. It can be shown that the cohomology class of the Chern forms do not depend on the choice of connection in V.

Using the matrix identity tr(ln(X))=ln(det(X)) and the Maclaurin series for ln(X+I), this expression for the Chern form expands as

Via an Euler class

One can define a Chern class in terms of an Euler class. This is the approach in the book by Milnor and Stasheff, and emphasizes the role of an orientation of a vector bundle.

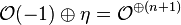

The basic observation is that a complex vector bundle comes with a canonical orientation, ultimately because  is connected. Hence, one simply defines the top Chern class of the bundle to be its Euler class (the Euler class of the underlying real vector bundle) and handles lower Chern classes in an inductive fashion.

is connected. Hence, one simply defines the top Chern class of the bundle to be its Euler class (the Euler class of the underlying real vector bundle) and handles lower Chern classes in an inductive fashion.

The precise construction is as follows. The idea is to do base change to get a bundle of one-less rank. Let π: E →B be a complex vector bundle over a paracompact space B. Thinking B is embedded into E as zero section, let  and define the new vector bundle:

and define the new vector bundle:

such that each fiber is the quotient of a fiber F of E by the line spanned by a nonzero vector v in F (a point of B' is specified by a fiber F of E and a nonzero vector on F.)[3] Then E' has rank one less than that of E. From the Gysin sequence for the fiber bundle  :

:

we see that  is an isomorphism for k < 2n - 1. Let

is an isomorphism for k < 2n - 1. Let

It then takes some work to check the axioms of Chern classes are satisfied for this definition.

See also: Thom space#The Thom isomorphism.

Examples

The complex tangent bundle of the Riemann sphere

Let CP1 be the Riemann sphere: 1-dimensional complex projective space. Suppose that z is a holomorphic local coordinate for the Riemann sphere. Let V = TCP1 be the bundle of complex tangent vectors having the form a∂/∂z at each point, where a is a complex number. We prove the complex version of the hairy ball theorem: V has no section which is everywhere nonzero.

For this, we need the following fact: the first Chern class of a trivial bundle is zero, i.e.,

This is evinced by the fact that a trivial bundle always admits a flat connection.

So, we shall show that

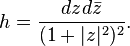

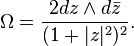

Consider the Kähler metric

One readily shows that the curvature 2-form is given by

Furthermore, by the definition of the first Chern class

We must show that this cohomology class is non-zero. It suffices to compute its integral over the Riemann sphere:

after switching to polar coordinates. By Stokes' theorem, an exact form would integrate to 0, so the cohomology class is nonzero.

This proves that TCP1 is not a trivial vector bundle.

Complex projective space

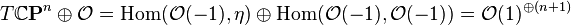

There is an exact sequence of sheaves/bundles:[4]

where  is the structure sheaf (i.e., the trivial line bundle),

is the structure sheaf (i.e., the trivial line bundle),  is Serre's twisting sheaf (i.e., the hyperplane bundle) and the last nonzero term is the tangent sheaf/bundle.

is Serre's twisting sheaf (i.e., the hyperplane bundle) and the last nonzero term is the tangent sheaf/bundle.

There are two ways to get the above sequence:

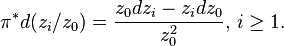

- [5] Let z0, … zn be the coordinates of

,

,  and

and  . Then we have:

. Then we have:

In other words, the cotangent sheaf

, which is a free

, which is a free  -module with the basis

-module with the basis  , fits into the exact sequence

, fits into the exact sequence are the basis of the middle term. The same sequence is clearly then exact on the whole projective space and the dual of it is the aforementioned sequence.

are the basis of the middle term. The same sequence is clearly then exact on the whole projective space and the dual of it is the aforementioned sequence. - Let L be a line in

that passes through the origin. It is elementary to see that the complex tangent space to

that passes through the origin. It is elementary to see that the complex tangent space to  at the point L is naturally the set of linear maps from L to its complement. Thus, the tangent bundle

at the point L is naturally the set of linear maps from L to its complement. Thus, the tangent bundle  can be identified with the hom bundle

can be identified with the hom bundle

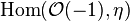

where η is the vector bundle such that

. It follows:

. It follows: .

.

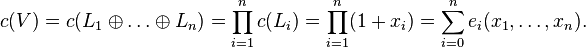

By the additivity of total Chern class c = 1 + c1 + c2 + … (i.e., the Whitney sum formula),

,

,

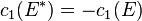

where a is the canonical generator of the cohomology group  ; i.e., the negative of the first Chern class of the tautological line bundle

; i.e., the negative of the first Chern class of the tautological line bundle  (note:

(note:  when E* is the dual of E.)

when E* is the dual of E.)

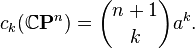

In particular, for any k ≥ 0,

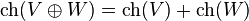

Chern polynomial

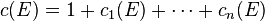

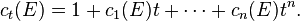

A Chern polynomial is a convenient way to handle Chern classes and related notions systematically. By definition, for a complex vector bundle E, the Chern polynomial ct of E is given by:

This is not a new invariant: the formal variable t simply keeps track of the degree of ck(E).[6] In particular,  is completely determined by the total Chern class of E:

is completely determined by the total Chern class of E:  and conversely.

and conversely.

The Whitney sum formula, one of the axioms of Chern classes (see below), says that ct is additive in the sense:

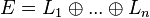

Now, if  is a direct sum of (complex) line bundles, then it follows from the sum formula that:

is a direct sum of (complex) line bundles, then it follows from the sum formula that:

where  are the first Chern classes. The roots

are the first Chern classes. The roots  , called the Chern roots of E, determine the coefficients of the polynomial: i.e.,

, called the Chern roots of E, determine the coefficients of the polynomial: i.e.,

where σk are elementary symmetric polynomials. In other words, thinking of ai as formal variables, ck "are" σk. A basic fact on symmetric polynomials is that any symmetric polynomial in, say, ti's is a polynomial in elementary symmetric polynomials in ti's. Either by splitting principle or by ring theory, any Chern polynomial  factorizes into linear factors after enlarging the cohomology ring; E need not be a direct sum of line bundles in the preceding discussion. The conclusion is

factorizes into linear factors after enlarging the cohomology ring; E need not be a direct sum of line bundles in the preceding discussion. The conclusion is

- "One can evaluate any symmetric polynomial f at a complex vector bundle E by writing f as a polynomial in σk and then replacing σk by ck(E)."

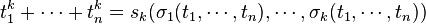

Example: We have polynomials sk

with  and so on (cf. Newton's identities). The sum

and so on (cf. Newton's identities). The sum

is called the Chern character of E, whose first few terms are: (we drop E from writing.)

Example: The Todd class of E is given by:

Remark: The observation that a Chern class is essentially an elementary symmetric polynomial can be used to "define" Chern classes. Let Gn be the infinite Grassmannian of n-dimensional complex vector spaces. It is a classifying space in the sense that, given a complex vector bundle E of rank n over X, there is a continuous map

unique up to homotopy. Borel's theorem says the cohomology ring of Gn is exactly the ring of symmetric polynomials, which are polynomials in elementary symmetric polynomials σk; so, the pullback of fE reads:

One then puts:

Remark: Any characteristic class is a polynomial in Chern classes, for the reason as follows. Let  be the contravariant functor that, to a CW complex X, assigns the set of isomorphism classes of complex vector bundles of rank n over X and, to a map, its pullback. By definition, a characteristic class is a natural transformation from

be the contravariant functor that, to a CW complex X, assigns the set of isomorphism classes of complex vector bundles of rank n over X and, to a map, its pullback. By definition, a characteristic class is a natural transformation from ![\operatorname{Vect}_n^{\mathbb{C}} = [-, G_n]](../I/m/3f9e7bf5f6edf2af9bfc3bafe0e573b8.png) to the cohomology functor

to the cohomology functor  Characteristic classes form a ring because of the ring structure of cohomology ring. Yoneda's lemma says this ring of characteristic classes is exactly the cohomology ring of Gn:

Characteristic classes form a ring because of the ring structure of cohomology ring. Yoneda's lemma says this ring of characteristic classes is exactly the cohomology ring of Gn:

Properties of Chern classes

Given a complex vector bundle E over a topological space X, the Chern classes of E are a sequence of elements of the cohomology of X. The k-th Chern class of E, which is usually denoted ck(V), is an element of

- H2k(X;Z),

the cohomology of X with integer coefficients. One can also define the total Chern class

Since the values are in integral cohomology groups, rather than cohomology with real coefficients, these Chern classes are slightly more refined than those in the Riemannian example.

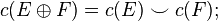

Classical axiomatic definition

The Chern classes satisfy the following four axioms:

Axiom 1.  for all E.

for all E.

Axiom 2. Naturality: If  is continuous and f*E is the vector bundle pullback of E, then

is continuous and f*E is the vector bundle pullback of E, then  .

.

Axiom 3. Whitney sum formula: If  is another complex vector bundle, then the Chern classes of the direct sum

is another complex vector bundle, then the Chern classes of the direct sum  are given by

are given by

that is,

Axiom 4. Normalization: The total Chern class of the tautological line bundle over CPk is 1−H, where H is Poincaré-dual to the hyperplane  .

.

Alexander Grothendieck axiomatic approach

Alternatively, Alexander Grothendieck (1958) replaced these with a slightly smaller set of axioms:

- Naturality: (Same as above)

- Additivity: If

is an exact sequence of vector bundles, then

is an exact sequence of vector bundles, then  .

.

- Normalization: If E is a line bundle, then

where

where  is the Euler class of the underlying real vector bundle.

is the Euler class of the underlying real vector bundle.

He shows using the Leray–Hirsch theorem that the total Chern class of an arbitrary finite rank complex vector bundle can be defined in terms of the first Chern class of a tautologically-defined line bundle.

Namely, introducing the projectivization P(E) of the rank n complex vector bundle E → B as the fiber bundle on B whose fiber at any point  is the projective space of the fiber Eb. The total space of this bundle P(E) is equipped with its tautological complex line bundle, that we denote τ, and the first Chern class

is the projective space of the fiber Eb. The total space of this bundle P(E) is equipped with its tautological complex line bundle, that we denote τ, and the first Chern class

restricts on each fiber P(Eb) to minus the (Poincaré-dual) class of the hyperplane, that spans the cohomology of the fiber, in view of the cohomology of complex projective spaces.

The classes

therefore form a family of ambient cohomology classes restricting to a basis of the cohomology of the fiber. The Leray–Hirsch theorem then states that any class in H*(P(E)) can be written uniquely as a linear combination of the 1, a, a2, ..., an−1 with classes on the basis as coefficients.

In particular, one may define the Chern classes of E in the sense of Grothendieck, denoted  by expanding this way the class

by expanding this way the class  , with the relation:

, with the relation:

One then may check that this alternative definition coincides with whatever other definition one may favor, or use the previous axiomatic characterization.

The top Chern class

In fact, these properties uniquely characterize the Chern classes. They imply, among other things:

- If n is the complex rank of V, then

for all k > n. Thus the total Chern class terminates.

for all k > n. Thus the total Chern class terminates.

- The top Chern class of V (meaning

, where n is the rank of V) is always equal to the Euler class of the underlying real vector bundle.

, where n is the rank of V) is always equal to the Euler class of the underlying real vector bundle.

Proximate notions

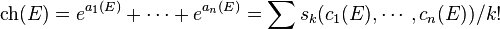

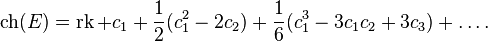

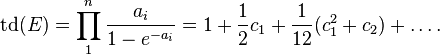

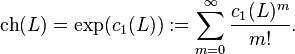

The Chern character

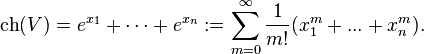

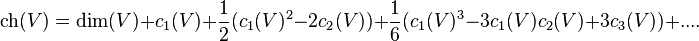

Chern classes can be used to construct a homomorphism of rings from the topological K-theory of a space to (the completion of) its rational cohomology. For a line bundle L, the Chern character ch is defined by

More generally, if  is a direct sum of line bundles, with first Chern classes

is a direct sum of line bundles, with first Chern classes  the Chern character is defined additively

the Chern character is defined additively

This can be rewritten as:[7]

This last expression, justified by invoking the splitting principle, is taken as the definition ch(V) for arbitrary vector bundles V.

If a connection is used to define the Chern classes when the base is a manifold (i.e., the Chern–Weil theory), then the explicit form of the Chern character is

where Ω is the curvature of the connection.

The Chern character is useful in part because it facilitates the computation of the Chern class of a tensor product. Specifically, it obeys the following identities:

As stated above, using the Grothendieck additivity axiom for Chern classes, the first of these identities can be generalized to state that ch is a homomorphism of abelian groups from the K-theory K(X) into the rational cohomology of X. The second identity establishes the fact that this homomorphism also respects products in K(X), and so ch is a homomorphism of rings.

The Chern character is used in the Hirzebruch-Riemann-Roch theorem.

Chern numbers

If we work on an oriented manifold of dimension 2n, then any product of Chern classes of total degree 2n can be paired with the orientation homology class (or "integrated over the manifold") to give an integer, a Chern number of the vector bundle. For example, if the manifold has dimension 6, there are three linearly independent Chern numbers, given by c13, c1c2, and c3. In general, if the manifold has dimension 2n, the number of possible independent Chern numbers is the number of partitions of n.

The Chern numbers of the tangent bundle of a complex (or almost complex) manifold are called the Chern numbers of the manifold, and are important invariants.

The Chern class in generalized cohomology theories

There is a generalization of the theory of Chern classes, where ordinary cohomology is replaced with a generalized cohomology theory. The theories for which such generalization is possible are called complex orientable. The formal properties of the Chern classes remain the same, with one crucial difference: the rule which computes the first Chern class of a tensor product of line bundles in terms of first Chern classes of the factors is not (ordinary) addition, but rather a formal group law.

Chern classes of manifolds with structure

The theory of Chern classes gives rise to cobordism invariants for almost complex manifolds.

If M is an almost complex manifold, then its tangent bundle is a complex vector bundle. The Chern classes of M are thus defined to be the Chern classes of its tangent bundle. If M is also compact and of dimension 2d, then each monomial of total degree 2d in the Chern classes can be paired with the fundamental class of M, giving an integer, a Chern number of M. If M′ is another almost complex manifold of the same dimension, then it is cobordant to M if and only if the Chern numbers of M′ coincide with those of M.

The theory also extends to real symplectic vector bundles, by the intermediation of compatible almost complex structures. In particular, symplectic manifolds have a well-defined Chern class.

Chern classes on arithmetic schemes and Diophantine equations

(See Arakelov geometry)

See also

- Pontryagin class

- Stiefel-Whitney class

- Euler class

- Segre class

Notes

- ↑ Tu, Raoul Bott ; Loring W. (1995). Differential forms in algebraic topology (Corr. 3. print. ed.). New York [u.a.]: Springer. p. 267ff. ISBN 3-540-90613-4.

- ↑ Proposition 3.10. in Hatcher's Vector Bundles and K-theory

- ↑ Editorial note: Our notation differs from Milnor−Stasheff, but seems more natural.

- ↑ The sequence is sometimes called the Euler sequence.

- ↑ Harshorne, Ch. II. Theorem 8.13.

- ↑ In a ring-theoretic term, there is an isomorphism of graded rings:

- ↑ (See also #Chern polynomial.) Observe that when V is a sum of line bundles, the Chern classes of V can be expressed as elementary symmetric polynomials in the

,

,  In particular, on the one hand

In particular, on the one hand

References

- Chern, S. S. (1946), "Characteristic classes of Hermitian Manifolds", Annals of Mathematics. Second Series (The Annals of Mathematics, Vol. 47, No. 1) 47 (1): 85–121, doi:10.2307/1969037, ISSN 0003-486X, JSTOR 1969037

- Grothendieck, Alexander (1958), "La théorie des classes de Chern", Bulletin de la Société Mathématique de France 86: 137–154, ISSN 0037-9484, MR 0116023

- Jost, Jürgen (2005), Riemannian Geometry and Geometric Analysis (4th ed.), Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-3-540-25907-7 (Provides a very short, introductory review of Chern classes).

- J.P. May, A Concise Course in Algebraic Topology. University of Chicago Press, 1999.

- Milnor, John Willard; Stasheff, James D. (1974), Characteristic classes, Annals of Mathematics Studies 76, Princeton University Press; University of Tokyo Press, ISBN 978-0-691-08122-9

- Rubei, Elena (2014), Algebraic Geometry, a concise dictionary, Berlin/Boston: Walter De Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-031622-3

External links

- Vector Bundles & K-Theory - A downloadable book-in-progress by Allen Hatcher. Contains a chapter about characteristic classes.

- Dieter Kotschick, Chern numbers of algebraic varieties

![\Omega=d\omega+\tfrac{1}{2}[\omega,\omega]](../I/m/7c472bd907af86fb2951c8f58b47eb38.png)

![\sum_k c_k(V) t^k = \left[ I

+ i \frac{\mathrm{tr}(\Omega)}{2\pi} t

+ \frac{\mathrm{tr}(\Omega^2)-\mathrm{tr}(\Omega)^2}{8\pi^2} t^2

+ i \frac{-2\mathrm{tr}(\Omega^3)+3\mathrm{tr}(\Omega^2)\mathrm{tr}(\Omega)-\mathrm{tr}(\Omega)^3}{48\pi^3} t^3

+ \cdots

\right].](../I/m/ed425b4139bd247337a669a4371551c3.png)

![c_1= \left[\frac{i}{2\pi} \mathrm{tr} \ \Omega\right] .](../I/m/c576e1ba7a21967a65e95743866f92ad.png)

![f_E^*: \mathbb{Z}[\sigma_1, \cdots, \sigma_n] \to H^*(X, \mathbb{Z}).](../I/m/df0e107f09c434321cf5aaddccb93079.png)

![\operatorname{Nat}([-, G_n], H^*(-, \mathbb{Z})) = H^*(G_n, \mathbb{Z}) = \mathbb{Z}[\sigma_1, \cdots, \sigma_n].](../I/m/405aa992764b71356b3dad6c98d68381.png)

![\hbox{ch}(V)=\left[\hbox{tr}\left(\exp\left(\frac{i\Omega}{2\pi}\right)\right)\right]](../I/m/e2c6f3bd1709a0480c66596b5b5d6699.png)

![H^{2*}(M, \mathbb{Z}) \to \oplus_k^\infty \eta(H^{2*}(M, \mathbb{Z})) [t], x \mapsto x t^{|x|/2}](../I/m/7473947a1215c1cc9d28e4147561542b.png)