Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy (often abbreviated to chemo and sometimes CTX or CTx) is a category of cancer treatment that uses chemical substances, especially one or more anti-cancer drugs (chemotherapeutic agents) that are given as part of a standardized chemotherapy regimen. Chemotherapy may be given with a curative intent, or it may aim to prolong life or to reduce symptoms (palliative chemotherapy). Along with hormonal therapy and targeted therapy, it is one of the major categories of medical oncology (pharmacotherapy for cancer). These modalities are often used in conjunction with other cancer treatments, such as radiation therapy, surgery, and/or hyperthermia therapy. Some chemotherapy drugs are also used to treat other conditions, including AL amyloidosis, ankylosing spondylitis, multiple sclerosis, Crohn's disease, psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, and scleroderma.

Traditional chemotherapeutic agents are cytotoxic, that is to say they act by killing cells that divide rapidly, one of the main properties of most cancer cells. This means that chemotherapy also harms cells that divide rapidly under normal circumstances: cells in the bone marrow, digestive tract, and hair follicles. This results in the most common side-effects of chemotherapy: myelosuppression (decreased production of blood cells, hence also immunosuppression), mucositis (inflammation of the lining of the digestive tract), and alopecia (hair loss).

Some newer anticancer drugs (for example, various monoclonal antibodies) are not indiscriminately cytotoxic, but rather target proteins that are abnormally expressed in cancer cells and that are essential for their growth. Such treatments are often referred to as targeted therapy (as distinct from classic chemotherapy) and are often used alongside traditional chemotherapeutic agents in antineoplastic treatment regimens.

Chemotherapy may use one drug at a time (single-agent chemotherapy) or several drugs at once (combination chemotherapy or polychemotherapy). The combination of chemotherapy and radiotherapy is chemoradiotherapy. Chemotherapy using drugs that convert to cytotoxic activity only upon light exposure is called photochemotherapy or photodynamic therapy.

History

The first use of drugs to treat cancer was in the early 20th century, although it was not originally intended for that purpose. Mustard gas was used as a chemical warfare agent during World War I and was discovered to be a potent suppressor of hematopoiesis (blood production).[1] A similar family of compounds known as nitrogen mustards were studied further during World War II at the Yale School of Medicine.[2] It was reasoned that an agent that damaged the rapidly growing white blood cells might have a similar effect on cancer.[2] Therefore, in December 1942, several patients with advanced lymphomas (cancers of the lymphatic system and lymph nodes) were given the drug by vein, rather than by breathing the irritating gas.[2] Their improvement, although temporary, was remarkable.[3] Concurrently, during a military operation in World War II, following a German air raid on the Italian harbour of Bari, several hundred people were accidentally exposed to mustard gas, which had been transported there by the Allied forces to prepare for possible retaliation in the event of German use of chemical warfare. The survivors were later found to have very low white blood cell counts.[4] After WWII was over and the reports declassified, the experiences converged and led researchers to look for other substances that might have similar effects against cancer. The first chemotherapy drug to be developed from this line of research was mustine. Since then, many other drugs have been developed to treat cancer, and drug development has exploded into a multibillion-dollar industry, although the principles and limitations of chemotherapy discovered by the early researchers still apply.[5]

The term chemotherapy

The word chemotherapy without a modifier usually refers to cancer treatment, but its historical meaning was broader. The term was coined in the early 1900s by Paul Ehrlich as meaning any use of chemicals to treat any disease (chemo- + -therapy), such as the use of antibiotics (antibacterial chemotherapy).[6] Ehrlich was not optimistic that effective chemotherapy drugs would be found for the treatment of cancer.[6] The first modern chemotherapeutic agent was arsphenamine, an arsenic compound discovered in 1907 and used to treat syphilis.[7] This was later followed by sulfonamides (sulfa drugs) and penicillin. In today's usage, the sense "any treatment of disease with drugs" is often expressed with the word pharmacotherapy.

General mode of action in cancer

Cancer is the uncontrolled growth of cells coupled with malignant behaviour: invasion and metastasis (among other features).[8] It is caused by the interaction between genetic susceptibility and environmental factors.[9][10] These factors lead to accumulations of genetic mutations in oncogenes (genes that promote cancer) and tumor suppressor genes (genes that help to prevent cancer), which gives cancer cells their malignant characteristics, such as uncontrolled growth.[11]

In the broad sense, most chemotherapeutic drugs work by impairing mitosis (cell division), effectively targeting fast-dividing cells. As these drugs cause damage to cells, they are termed cytotoxic. They prevent mitosis by various mechanisms including damaging DNA and inhibition of the cellular machinery involved in cell division.[12][13] One theory as to why these drugs kill cancer cells is that they induce a programmed form of cell death known as apoptosis.[14]

As chemotherapy affects cell division, tumors with high growth rates (such as acute myelogenous leukemia and the aggressive lymphomas, including Hodgkin's disease) are more sensitive to chemotherapy, as a larger proportion of the targeted cells are undergoing cell division at any time. Malignancies with slower growth rates, such as indolent lymphomas, tend to respond to chemotherapy much more modestly.[15] Heterogeneic tumours may also display varying sensitivities to chemotherapy agents, depending on the subclonal populations within the tumor.

Types

Alkylating agents

Alkylating agents are the oldest group of chemotherapeutics in use today. Originally derived from mustard gas used in World War I, there are now many types of alkylating agents in use.[15] They are so named because of their ability to alkylate many molecules, including proteins, RNA and DNA. This ability to bind covalently to DNA via their alkyl group is the primary cause for their anti-cancer effects.[17] DNA is made of two strands and the molecules may either bind twice to one strand of DNA (intrastrand crosslink) or may bind once to both strands (interstrand crosslink). If the cell tries to replicate crosslinked DNA during cell division, or tries to repair it, the DNA strands can break. This leads to a form of programmed cell death called apoptosis.[16][18] Alkylating agents will work at any point in the cell cycle and thus are known as cell cycle-independent drugs. For this reason the effect on the cell is dose dependent; the fraction of cells that die is directly proportional to the dose of drug.[13]

The subtypes of alkylating agents are the nitrogen mustards, nitrosoureas, tetrazines, aziridines,[19] cisplatins and derivatives, and non-classical alkylating agents. Nitrogen mustards include mechlorethamine, cyclophosphamide, melphalan, chlorambucil, ifosfamide and busulfan. Nitrosoureas include N-Nitroso-N-methylurea (MNU), carmustine (BCNU), lomustine (CCNU) and semustine (MeCCNU), fotemustine and streptozotocin. Tetrazines include dacarbazine, mitozolomide and temozolomide. Aziridines include thiotepa, mytomycin and diaziquone (AZQ). Cisplatin and derivatives include cisplatin, carboplatin and oxaliplatin.[17][18] They impair cell function by forming covalent bonds with the amino, carboxyl, sulfhydryl, and phosphate groups in biologically important molecules.[20] Non-classical alkylating agents include procarbazine and hexamethylmelamine.[17][18]

Antimetabolites

Anti-metabolites are a group of molecules that impede DNA and RNA synthesis. Many of them have a similar structure to the building blocks of DNA and RNA. The building blocks are nucleotides; a molecule comprising a nucleobase, a sugar and a phosphate group. The nucleobases are divided into purines (guanine and adenine) and pyrimidines (cytosine, thymine and uracil). Anti-metabolites resemble either nucleobases or nucleosides (a nucleotide without the phosphate group), but have altered chemical groups.[21] These drugs exert their effect by either blocking the enzymes required for DNA synthesis or becoming incorporated into DNA or RNA. By inhibiting the enzymes involved in DNA synthesis, they prevent mitosis because the DNA cannot duplicate itself. Also, after misincorperation of the molecules into DNA, DNA damage can occur and programmed cell death (apoptosis) is induced. Unlike alkylating agents, anti-metabolites are cell cycle dependent. This means that they only work during a specific part of the cell cycle, in this case S-phase (the DNA synthesis phase). For this reason, at a certain dose, the effect plateaus and proportionally no more cell death occurs with increased doses. Subtypes of the anti-metabolites are the anti-folates, fluoropyrimidines, deoxynucleoside analogues and thiopurines.[17][21]

The anti-folates include methotrexate and pemetrexed. Methotrexate inhibits dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR), an enzyme that regenerates tetrahydrofolate from dihydrofolate. When the enzyme is inhibited by methotrexate, the cellular levels of folate coenzymes diminish. These are required for thymidylate and purine production, which are both essential for DNA synthesis and cell division.[22][23] Pemetrexed is another anti-metabolite that affects purine and pyrimidine production, and therefore also inhibits DNA synthesis. It primarily inhibits the enzyme thymidylate synthase, but also has effects on DHFR, aminoimidazole carboxamide ribonucleotide formyltransferase and glycinamide ribonucleotide formyltransferase.[24] The fluoropyrimidines include fluorouracil and capecitabine. Fluorouracil is a nucleobase analogue that is metabolised in cells to form at least two active products; 5-fluourouridine monophosphate (FUMP) and 5-fluoro-2'-deoxyuridine 5'-phosphate (fdUMP). FUMP becomes incorporated into RNA and fdUMP inhibits the enzyme thymidylate synthase; both of which lead to cell death.[22] Capecitabine is a prodrug of 5-fluorouracil that is broken down in cells to produce the active drug.[25] The deoxynucleoside analogues include cytarabine, gemcitabine, decitabine, Vidaza, fludarabine, nelarabine, cladribine, clofarabine and pentostatin. The thiopurines include thioguanine and mercaptopurine.[17][21]

Anti-microtubule agents

Anti-microtubule agents are plant-derived chemicals that block cell division by preventing microtubule function. Microtubules are an important cellular structure composed of two proteins; α-tubulin and β-tubulin. They are hollow rod shaped structures that are required for cell division, among other cellular functions.[26] Microtubules are dynamic structures, which means that they are permanently in a state of assembly and disassembly. Vinca alkaloids and taxanes are the two main groups of anti-microtubule agents, and although both of these groups of drugs cause microtubule dysfunction, their mechanisms of action are completely opposite. The vinca alkaloids prevent the formation of the microtubules, whereas the taxanes prevent the microtubule disassembly. By doing so, they prevent the cancer cells from completing mitosis. Following this, cell cycle arrest occurs, which induces programmed cell death (apoptosis).[17][27] Also, these drugs can affect blood vessel growth; an essential process that tumours utilise in order to grow and metastasise.[27]

Vinca alkaloids are derived from the Madagascar periwinkle, Catharanthus roseus (formerly known as Vinca rosea). They bind to specific sites on tubulin, inhibiting the assembly of tubulin into microtubules. The original vinca alkaloids are completely natural chemicals that include vincristine and vinblastine. Following the success of these drugs, semi-synthetic vinca alkaloids were produced: vinorelbine, vindesine, and vinflunine.[27] These drugs are cell cycle-specific. They bind to the tubulin molecules in S-phase and prevent proper microtubule formation required for M-phase.[13]

Taxanes are natural and semi-synthetic drugs. The first drug of their class, paclitaxel, was originally extracted from the Pacific Yew tree, Taxus brevifolia. Now this drug and another in this class, docetaxel, are produced semi-synthetically from a chemical found in the bark of another Yew tree; Taxus baccata. These drugs promote microtubule stability, preventing their disassembly. Paclitaxel prevents the cell cycle at the boundary of G2-M, whereas docetaxel exerts its effect during S-phase. Taxanes present difficulties in formulation as medicines because they are poorly soluble in water.[27]

Podophyllotoxin is an antineoplastic lignan obtained primarily from the American Mayapple (Podophyllum peltatum) and Himalayan Mayapple (Podophyllum hexandrum or Podophyllum emodi). It has anti-microtubule activity, and its mechanism is similar to that of vinca alkaloids in that they bind to tubulin, inhibiting microtubule formation. Podophyllotoxin is used to produce two other drugs with different mechanisms of action: etoposide and teniposide.[28][29]

Topoisomerase inhibitors

Topoisomerase inhibitors are drugs that affect the activity of two enzymes: topoisomerase I and topoisomerase II. When the DNA double-strand helix is unwound, during DNA replication or transcription, for example, the adjacent unopened DNA winds tighter (supercoils), like opening the middle of a twisted rope. The stress caused by this effect is in part aided by the topoisomerase enzymes. They produce single- or double-strand breaks into DNA, reducing the tension in the DNA strand. This allows the normal unwinding of DNA to occur during replication or transcription. Inhibition of topoisomerase I or II interferes with both of these processes.[30][31]

Two topoisomerase I inhibitors, irinotecan and topotecan, are semi-synthetically derived from camptothecin, which is obtained from the Chinese ornamental tree Camptotheca acuminata.[13] Drugs that target topoisomerase II can be divided into two groups. The topoisomerase II poisons cause increased levels enzymes bound to DNA. This prevents DNA replication and transcription, causes DNA strand breaks, and leads to programmed cell death (apoptosis). These agents include etoposide, doxorubicin, mitoxantrone and teniposide. The second group, catalytic inhibitors, are drugs that block the activity of topoisomerase II, and therefore prevent DNA synthesis and translation because the DNA cannot unwind properly. This group includes novobiocin, merbarone, and aclarubicin, which also have other significant mechanisms of action.[32]

Cytotoxic antibiotics

The cytotoxic antibiotics are a varied group of drugs that have various mechanisms of action. The group includes the anthracyclines and other drugs including actinomycin, bleomycin, plicamycin, and mitomycin. Doxorubicin and daunorubicin were the first two anthracyclines, and were obtained from the bacterium Streptomyces peucetius. Derivatives of these compounds include epirubicin and idarubicin. Other clinically used drugs in the anthracyline group are pirarubicin, aclarubicin, and mitoxantrone. The mechanisms of anthracyclines include DNA intercalation (molecules insert between the two strands of DNA), generation of highly reactive free radicals that damage intercellular molecules and topoisomerase inhibition.[33] Actinomycin is a complex molecule that intercalates DNA and prevents RNA synthesis.[34] Bleomycin, a glycopeptide isolated from Streptomyces verticillus, also intercalates DNA, but produces free radicals that damage DNA. This occurs when bleomycin binds to a metal ion, becomes chemically reduced and reacts with oxygen.[35][36] Mitomycin is a cytotoxic antibiotic with the ability to alkylate DNA.[37]

Treatment strategies

| Cancer type | Drugs | Acronym |

|---|---|---|

| Breast cancer | Cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, 5-fluorouracil | CMF |

| Doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide | AC | |

| Hodgkin's disease | Mustine, vincristine, procarbazine, prednisolone | MOPP |

| Doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine | ABVD | |

| Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma | Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisolone | CHOP |

| Germ cell tumor | Bleomycin, etoposide, cisplatin | BEP |

| Stomach cancer | Epirubicin, cisplatin, 5-fluorouracil | ECF |

| Epirubicin, cisplatin, capecitabine | ECX | |

| Bladder cancer | Methotrexate, vincristine, doxorubicin, cisplatin | MVAC |

| Lung cancer | Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, | CAV |

| Colorectal cancer | 5-fluorouracil, folinic acid, oxaliplatin | FOLFOX |

There are a number of strategies in the administration of chemotherapeutic drugs used today. Chemotherapy may be given with a curative intent or it may aim to prolong life or to palliate symptoms.

- Combined modality chemotherapy is the use of drugs with other cancer treatments, such as radiation therapy, surgery and/or hyperthermia therapy.

- Induction chemotherapy is the first line treatment of cancer with a chemotherapeutic drug. This type of chemotherapy is used for curative intent.[23]

- Consolidation chemotherapy is given after remission in order to prolong the overall disease-free time and improve overall survival. The drug that is administered is the same as the drug that achieved remission.[23]

- Intensification chemotherapy is identical to consolidation chemotherapy but a different drug than the induction chemotherapy is used.[23]

- Combination chemotherapy involves treating a patient with a number of different drugs simultaneously. The drugs differ in their mechanism and side-effects. The biggest advantage is minimising the chances of resistance developing to any one agent. Also, the drugs can often be used at lower doses, reducing toxicity.[23][38]

- Neoadjuvant chemotherapy is given prior to a local treatment such as surgery, and is designed to shrink the primary tumor.[23] It is also given to cancers with a high risk of micrometastatic disease.[39]

- Adjuvant chemotherapy is given after a local treatment (radiotherapy or surgery). It can be used when there is little evidence of cancer present, but there is risk of recurrence.[23] It is also useful in killing any cancerous cells that have spread to other parts of the body. These micrometastases can be treated with adjuvant chemotherapy and can reduce relapse rates caused by these disseminated cells.[40]

- Maintenance chemotherapy is a repeated low-dose treatment to prolong remission.[23]

- Salvage chemotherapy or palliative chemotherapy is given without curative intent, but simply to decrease tumor load and increase life expectancy. For these regimens, in general, a better toxicity profile is expected.[23]

All chemotherapy regimens require that the patient be capable of undergoing the treatment. Performance status is often used as a measure to determine whether a patient can receive chemotherapy, or whether dose reduction is required. Because only a fraction of the cells in a tumor die with each treatment (fractional kill), repeated doses must be administered to continue to reduce the size of the tumor.[41] Current chemotherapy regimens apply drug treatment in cycles, with the frequency and duration of treatments limited by toxicity to the patient.[42]

Dosage

Dosage of chemotherapy can be difficult: If the dose is too low, it will be ineffective against the tumor, whereas, at excessive doses, the toxicity (side-effects) will be intolerable to the patient.[15] The standard method of determining chemotherapy dosage is based on calculated body surface area (BSA). The BSA is usually calculated with a mathematical formula or a nomogram, using a patient's weight and height, rather than by direct measurement of body mass. This formula was originally derived in a 1916 study and attempted to translate medicinal doses established with laboratory animals to equivalent doses for humans.[43] The study only included 9 human subjects.[44] When chemotherapy was introduced in the 1950s, the BSA formula was adopted as the official standard for chemotherapy dosing for lack of a better option.[45][46]

Recently, the validity of this method in calculating uniform doses has been questioned. The reason for this is that the formula only takes into account the individual's weight and height. Drug absorption and clearance are influenced by multiple factors, including age, gender, metabolism, disease state, organ function, drug-to-drug interactions, genetics, and obesity, which has a major impact on the actual concentration of the drug in the patient's bloodstream.[45][47][48] As a result, there is high variability in the systemic chemotherapy drug concentration among patients dosed by BSA, and this variability has been demonstrated to be more than 10-fold for many drugs.[44][49] In other words, if two patients receive the same dose of a given drug based on BSA, the concentration of that drug in the bloodstream of one patient may be 10 times higher or lower compared to that of the other patient.[49] This variability is typical with many chemotherapy drugs dosed by BSA, and, as shown below, was demonstrated in a study of 14 common chemotherapy drugs.[44]

The result of this pharmacokinetic variability among patients is that many patients do not receive the right dose to achieve optimal treatment effectiveness with minimized toxic side effects. Some patients are overdosed while others are underdosed.[45][47][48][50][51][52][53] For example, in a randomized clinical trial, investigators found 85% of metastatic colorectal cancer patients treated with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) did not receive the optimal therapeutic dose when dosed by the BSA standard—68% were underdosed and 17% were overdosed.[50]

There has been recent controversy over the use of BSA to calculate chemotherapy doses for obese patients.[54] Because of their higher BSA, clinicians often arbitrarily reduce the dose prescribed by the BSA formula for fear of overdosing.[54] In many cases, this can result in sub-optimal treatment.[54]

Several clinical studies have demonstrated that when chemotherapy dosing is individualized to achieve optimal systemic drug exposure, treatment outcomes are improved and toxic side effects are reduced.[50][52] In the 5-FU clinical study cited above, patients whose dose was adjusted to achieve a pre-determined target exposure realized an 84% improvement in treatment response rate and a six-month improvement in overall survival (OS) compared with those dosed by BSA.[50]

In the same study, investigators compared the incidence of common 5-FU-associated grade 3/4 toxicities between the dose-adjusted patients and the BSA-dosed patients.[50] The incidence of debilitating grades of diarrhea was reduced from 18% in the BSA-dosed group to 4% in the dose-adjusted group of patients and serious hematologic side effects were eliminated.[50] Because of the reduced toxicity, dose-adjusted patients were able to be treated for longer periods of time.[50] BSA-dosed patients were treated for a total of 680 months while dose-adjusted patients were treated for a total of 791 months.[50] Completing the course of treatment is an important factor in achieving better treatment outcomes.

Similar results were found in a study involving colorectal cancer patients treated with the popular FOLFOX regimen.[52] The incidence of serious diarrhea was reduced from 12% in the BSA-dosed group of patients to 1.7% in the dose-adjusted group, and the incidence of severe mucositis was reduced from 15% to 0.8%.[52]

The FOLFOX study also demonstrated an improvement in treatment outcomes.[52] Positive response increased from 46% in the BSA-dosed patients to 70% in the dose-adjusted group. Median progression free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) both improved by six months in the dose adjusted group.[52]

One approach that can help clinicians individualize chemotherapy dosing is to measure the drug levels in blood plasma over time and adjust dose according to a formula or algorithm to achieve optimal exposure. With an established target exposure for optimized treatment effectiveness with minimized toxicities, dosing can be personalized to achieve target exposure and optimal results for each patient. Such an algorithm was used in the clinical trials cited above and resulted in significantly improved treatment outcomes.

Oncologists are already individualizing dosing of some cancer drugs based on exposure. Carboplatin[55] and busulfan[56][57] dosing rely upon results from blood tests to calculate the optimal dose for each patient. Simple blood tests are also available for dose optimization of methotrexate,[58] 5-FU, paclitaxel, and docetaxel.[59][60]

Delivery

Most chemotherapy is delivered intravenously, although a number of agents can be administered orally (e.g., melphalan, busulfan, capecitabine).

There are many intravenous methods of drug delivery, known as vascular access devices. These include the winged infusion device, peripheral cannula, midline catheter, peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC), central venous catheter and implantable port. The devices have different applications regarding duration of chemotherapy treatment, method of delivery and types of chemotherapeutic agent.[61]

Depending on the patient, the cancer, the stage of cancer, the type of chemotherapy, and the dosage, intravenous chemotherapy may be given on either an inpatient or an outpatient basis. For continuous, frequent or prolonged intravenous chemotherapy administration, various systems may be surgically inserted into the vasculature to maintain access.[62] Commonly used systems are the Hickman line, the Port-a-Cath, and the PICC line. These have a lower infection risk, are much less prone to phlebitis or extravasation, and eliminate the need for repeated insertion of peripheral cannulae.

Isolated limb perfusion (often used in melanoma),[63] or isolated infusion of chemotherapy into the liver[64] or the lung have been used to treat some tumors. The main purpose of these approaches is to deliver a very high dose of chemotherapy to tumor sites without causing overwhelming systemic damage.[65] These approaches can help control solitary or limited metastases, but they are by definition not systemic, and, therefore, do not treat distributed metastases or micrometastases.

Topical chemotherapies, such as 5-fluorouracil, are used to treat some cases of non-melanoma skin cancer.[66]

If the cancer has central nervous system involvement, or with meningeal disease, intrathecal chemotherapy may be administered.[15]

Adverse effects

Chemotherapeutic techniques have a range of side-effects that depend on the type of medications used. The most common medications affect mainly the fast-dividing cells of the body, such as blood cells and the cells lining the mouth, stomach, and intestines. Chemotherapy-related toxicities can occur acutely after administration, within hours or days, or chronically, from weeks to years.[67]

Immunosuppression and myelosuppression

Virtually all chemotherapeutic regimens can cause depression of the immune system, often by paralysing the bone marrow and leading to a decrease of white blood cells, red blood cells, and platelets. Anemia and thrombocytopenia, when they occur, are improved with blood transfusion. Neutropenia (a decrease of the neutrophil granulocyte count below 0.5 x 109/litre) can be improved with synthetic G-CSF (granulocyte-colony-stimulating factor, e.g., filgrastim, lenograstim).

In very severe myelosuppression, which occurs in some regimens, almost all the bone marrow stem cells (cells that produce white and red blood cells) are destroyed, meaning allogenic or autologous bone marrow cell transplants are necessary. (In autologous BMTs, cells are removed from the patient before the treatment, multiplied and then re-injected afterward; in allogenic BMTs, the source is a donor.) However, some patients still develop diseases because of this interference with bone marrow.

Although patients are encouraged to wash their hands, avoid sick people, and take other infection-reducing steps, about 85% of infections are due to naturally occurring microorganisms in the patient's own gastrointestinal tract (including oral cavity) and skin.[68] This may manifest as systemic infections, such as sepsis, or as localized outbreaks, such as Herpes simplex, shingles, or other members of the Herpesviridea.[69] Sometimes, chemotherapy treatments are postponed because the immune system is suppressed to a critically low level.

In Japan, the government has approved the use of some medicinal mushrooms like Trametes versicolor, to counteract depression of the immune system in patients undergoing chemotherapy.[70]

Typhlitis

Due to immune system suppression, typhlitis is a "life-threatening gastrointestinal complication of chemotherapy."[71] Typhlitis is an intestinal infection which may manifest itself through symptoms including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, a distended abdomen, fever, chills, or abdominal pain and tenderness.

Typhlitis is a medical emergency. It has a very poor prognosis and is often fatal unless promptly recognized and aggressively treated.[72] Successful treatment hinges on early diagnosis provided by a high index of suspicion and the use of CT scanning, nonoperative treatment for uncomplicated cases, and sometimes elective right hemicolectomy to prevent recurrence.[72]

Gastrointestinal distress

Nausea, vomiting, anorexia, diarrhoea, abdominal cramps, and constipation are common side-effects of chemotherapeutic medications that kill fast-dividing cells.[73] Malnutrition and dehydration can result when the patient does not eat or drink enough, or when the patient vomits frequently, because of gastrointestinal damage. This can result in rapid weight loss, or occasionally in weight gain, if the patient eats too much in an effort to allay nausea or heartburn. Weight gain can also be caused by some steroid medications. These side-effects can frequently be reduced or eliminated with antiemetic drugs. Self-care measures, such as eating frequent small meals and drinking clear liquids or ginger tea, are often recommended. In general, this is a temporary effect, and frequently resolves within a week of finishing treatment. However, a high index of suspicion is appropriate, since diarrhea and bloating are also symptoms of typhlitis, a very serious and potentially life-threatening medical emergency that requires immediate treatment.

Anemia

Anemia in cancer patients can be a combined outcome caused by myelosuppressive chemotherapy, and possible cancer-related causes such as bleeding, blood cell destruction (hemolysis), hereditary disease, kidney dysfunction, nutritional deficiencies and/or anemia of chronic disease. Treatments to mitigate anemia include hormones to boost blood production (erythropoietin), iron supplements, and blood transfusions.[74][75][76] Myelosuppressive therapy can cause a tendency to bleed easily, leading to anemia. Medications that kill rapidly dividing cells or blood cells can reduce the number of platelets in the blood, which can result in bruises and bleeding. Extremely low platelet counts may be temporarily boosted through platelet transfusions and new drugs to increase platelet counts during chemotherapy are being developed.[77][78] Sometimes, chemotherapy treatments are postponed to allow platelet counts to recover.

Fatigue

Fatigue may be a consequence of the cancer or its treatment, and can last for months to years after treatment. One physiological cause of fatigue is anemia, which can be caused by chemotherapy, surgery, radiotherapy, primary and metastatic disease and/or nutritional depletion.[79][80] Anaerobic exercise has been found to be beneficial in reducing fatigue in people with solid tumours.[81]

Nausea and vomiting

Nausea and vomiting are two of the most feared cancer treatment-related side-effects for cancer patients and their families. In 1983, Coates et al. found that patients receiving chemotherapy ranked nausea and vomiting as the first and second most severe side-effects, respectively. Up to 20% of patients receiving highly emetogenic agents in this era postponed, or even refused, potentially curative treatments.[82] Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) are common with many treatments and some forms of cancer. Since the 1990s, several novel classes of antiemetics have been developed and commercialized, becoming a nearly universal standard in chemotherapy regimens, and helping to successfully manage these symptoms in a large portion of patients. Effective mediation of these unpleasant and sometimes-crippling symptoms results in increased quality of life for the patient and more efficient treatment cycles, due to less stoppage of treatment due to better tolerance by the patient, and due to better overall health of the patient.

Hair loss

Hair loss (Alopecia) can be caused by chemotherapy that kills rapidly dividing cells; other medications may cause hair to thin. These are most often temporary effects: hair usually starts to regrow a few weeks after the last treatment, and sometimes can change colour, texture, thickness and style. Sometimes hair has a tendency to curl after regrowth, resulting in "chemo curls." Severe hair loss occurs most often with drugs such as doxorubicin, daunorubicin, paclitaxel, docetaxel, cyclophosphamide, ifosfamide and etoposide. Permanent thinning or hair loss can result from some standard chemotherapy regimens.

Chemotherapy induced hair loss occurs by a non-androgenic mechanism, and can manifests as alopecia totalis, telogen effluvium, or less often alopecia areata.[83] It is usually associated with systemic treatment due to the high mitotic rate of hair follicles, and more reversible than androgenic hair loss,[84][85] although permanent cases can occur.[86] Chemotherapy induces hair loss in women more often than men.[87]

Scalp cooling offers a means of preventing both permanent and temporary hair loss; however, concerns for this method have been raised.[88][89]

Secondary neoplasm

Development of secondary neoplasia after successful chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy treatment can occur. The most common secondary neoplasm is secondary acute myeloid leukemia, which develops primarily after treatment with alkylating agents or topoisomerase inhibitors.[90] Survivors of childhood cancer are more than 13 times as likely to get a secondary neoplasm during the 30 years after treatment than the general population.[91] Not all of this increase can be attributed to chemotherapy.

Infertility

Some types of chemotherapy are gonadotoxic and may cause infertility.[92] Chemotherapies with high risk include procarbazine and other alkylating drugs such as cyclophosphamide, ifosfamide, busulfan, melphalan, chlorambucil, and chlormethine.[92] Drugs with medium risk include doxorubicin and platinum analogs such as cisplatin and carboplatin.[92] On the other hand, therapies with low risk of gonadotoxicity include plant derivatives such as vincristine and vinblastine, antibiotics such as bleomycin and dactinomycin, and antimetabolites such as methotrexate, mercaptopurine, and 5-fluorouracil.[92]

Female infertility by chemotherapy appears to be secondary to premature ovarian failure by loss of primordial follicles.[93] This loss is not necessarily a direct effect of the chemotherapeutic agents, but could be due to an increased rate of growth initiation to replace damaged developing follicles.[93]

Patients may choose between several methods of fertility preservation prior to chemotherapy, including cryopreservation of semen, ovarian tissue, oocytes, or embryos.[94] As more than half of cancer patients are elderly, this adverse effect is only relevant for a minority of patients. A study in France between 1999 and 2011 came to the result that embryo freezing before administration of gonadotoxic agents to females caused a delay of treatment in 34% of cases, and a live birth in 27% of surviving cases who wanted to become pregnant, with the follow-up time varying between 1 and 13 years.[95]

Potential protective or attenuating agents include GnRH analogs, where several studies have shown a protective effect in vivo in humans, but some studies show no such effect. Sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) has shown similar effect, but its mechanism of inhibiting the sphingomyelin apoptotic pathway may also interfere with the apoptosis action of chemotherapy drugs.[96]

In chemotherapy as a conditioning regimen in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, a study of patients conditioned with cyclophosphamide alone for severe aplastic anemia came to the result that ovarian recovery occurred in all women younger than 26 years at time of transplantation, but only in five of 16 women older than 26 years.[97]

Teratogenicity

Chemotherapy is potentially teratogenic during pregnancy, especially during the first trimester, to the extent that abortion usually is recommended if pregnancy in this period is found during chemotherapy.[98] Second- and third-trimester exposure does not usually increase the teratogenic risk and adverse effects on cognitive development, but it may increase the risk of various complications of pregnancy and fetal myelosuppression.[98]

In males previously having undergone chemotherapy or radiotherapy, there appears to be no increase in genetic defects or congenital malformations in their children conceived after therapy.[98] The use of assisted reproductive technologies and micromanipulation techniques might increase this risk.[98] In females previously having undergone chemotherapy, miscarriage and congenital malformations are not increased in subsequent conceptions.[98] However, when in vitro fertilization and embryo cryopreservationis practised between or shortly after treatment, possible genetic risks to the growing oocytes exist, and hence it has been recommended that the babies be screened.[98]

Peripheral neuropathy

Between 30 and 40 percent of patients undergoing chemotherapy experience chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN), a progressive, enduring, and often irreversible condition, causing pain, tingling, numbness and sensitivity to cold, beginning in the hands and feet and sometimes progressing to the arms and legs.[99] Chemotherapy drugs associated with CIPN include thalidomide, epothilones, vinca alkaloids, taxanes, proteasome inhibitors, and the platinum-based drugs.[99][100][101] Whether CIPN arises, and to what degree, is determined by the choice of drug, duration of use, the total amount consumed and whether the patient already has peripheral neuropathy. Though the symptoms are mainly sensory, in some cases motor nerves and the autonomic nervous system are affected.[102] CIPN often follows the first chemotherapy dose and increases in severity as treatment continues, but this progression usually levels off at completion of treatment. The platinum-based drugs are the exception; with these drugs, sensation may continue to deteriorate for several months after the end of treatment.[103] Some CIPN appears to be irreversible.[103] Pain can often be managed with drug or other treatment but the numbness is usually resistant to treatment.[104]

Cognitive impairment

Some patients report fatigue or non-specific neurocognitive problems, such as an inability to concentrate; this is sometimes called post-chemotherapy cognitive impairment, referred to as "chemo brain" by patients' groups.[105]

Tumor lysis syndrome

In particularly large tumors and cancers with high white cell counts, such as lymphomas, teratomas, and some leukemias, some patients develop tumor lysis syndrome. The rapid breakdown of cancer cells causes the release of chemicals from the inside of the cells. Following this, high levels of uric acid, potassium and phosphate are found in the blood. High levels of phosphate induce secondary hypoparathyroidism, resulting in low levels of calcium in the blood. This causes kidney damage and the high levels of potassium can cause cardiac arrhythmia. Although prophylaxis is available and is often initiated in patients with large tumors, this is a dangerous side-effect that can lead to death if left untreated.[106]

Organ damage

Cardiotoxicity (heart damage) is especially prominent with the use of anthracycline drugs (doxorubicin, epirubicin, idarubicin, and liposomal doxorubicin). The cause of this is most likely due to the production of free radicals in the cell and subsequent DNA damage. Other chemotherapeutic agents that cause cardiotoxicity, but at a lower incidence, are cyclophosphamide, docetaxel and clofarabine.[107]

Hepatotoxicity (liver damage) can be caused by many cytotoxic drugs. The susceptibility of an individual to liver damage can be altered by other factors such as the cancer itself, viral hepatitis, immunosuppression and nutritional deficiency. The liver damage can consist of damage to liver cells, hepatic sinusoidal syndrome (obstruction of the veins in the liver), cholestasis (where bile does not flow from the liver to the intestine) and liver fibrosis.[108][109]

Nephrotoxicity (kidney damage) can be caused by tumor lysis syndrome and also due direct effects of drug clearance by the kidneys. Different drugs will affect different parts of the kidney and the toxicity may be asymptomatic (only seen on blood or urine tests) or may cause acute renal failure.[110][111]

Ototoxicity (damage to the inner ear) is a common side effect of platinum based drugs that can produce symptoms such as dizziness and vertigo.[112][113]

Other side-effects

Less common side-effects include red skin (erythema), dry skin, damaged fingernails, a dry mouth (xerostomia), water retention, and sexual impotence. Some medications can trigger allergic or pseudoallergic reactions.

Specific chemotherapeutic agents are associated with organ-specific toxicities, including cardiovascular disease(e.g., doxorubicin), interstitial lung disease (e.g., bleomycin) and occasionally secondary neoplasm (e.g., MOPP therapy for Hodgkin's disease).

Limitations

Chemotherapy does not always work, and even when it is useful, it may not completely destroy the cancer. Patients frequently fail to understand its limitations. In one study of patients who had been newly diagnosed with incurable, stage 4 cancer, more than two-thirds of patients with lung cancer and more than four-fifths of patients with colorectal cancer still believed that chemotherapy was likely to cure their cancer.[114]

The blood–brain barrier poses a difficult obstacle to pass to deliver chemotherapy to the brain. This is because the brain has an extensive system in place to protect it from harmful chemicals. Drug transporters can pump out drugs from the brain and brain's blood vessel cells into the cerebrospinal fluid and blood circulation. These transporters pump out most chemotherapy drugs, which reduces their efficacy for treatment of brain tumors. Only small lipophilic alkylating agents such as lomustine or temozolomide are able to cross this blood–brain barrier.[115][116][117]

Blood vessels in tumors are very different from those seen in normal tissues. As a tumor grows, tumor cells furthest away from the blood vessels become low in oxygen (hypoxic). To counteract this they then signal for new blood vessels to grow. The newly formed tumor vasculature is poorly formed and does not deliver an adequate blood supply to all areas of the tumor. This leads to issues with drug delivery because many drugs will be delivered to the tumor by the circulatory system.[118]

Efficacy

The efficacy of chemotherapy depends on the type of cancer and the stage. The overall effectiveness ranges from being curative for some cancers, such as some leukemias,[119][120] to being ineffective, such as in some brain tumors,[121] to being needless in others, like most non-melanoma skin cancers.[122]

Even when it is impossible for chemotherapy to provide a permanent cure, chemotherapy may be useful to reduce symptoms like pain or to reduce the size of an inoperable tumor in the hope that surgery will be possible in the future.

Resistance

Resistance is a major cause of treatment failure in chemotherapeutic drugs. There are a few possible causes of resistance in cancer, one of which is the presence of small pumps on the surface of cancer cells that actively move chemotherapy from inside the cell to the outside. Cancer cells produce high amounts of these pumps, known as p-glycoprotein, in order to protect themselves from chemotherapeutics. Research on p-glycoprotein and other such chemotherapy efflux pumps is currently ongoing. Medications to inhibit the function of p-glycoprotein are undergoing investigation, but due to toxicities and interactions with anti-cancer drugs their development has been difficult.[123][124] Another mechanism of resistance is gene amplification, a process in which multiple copies of a gene are produced by cancer cells. This overcomes the effect of drugs that reduce the expression of genes involved in replication. With more copies of the gene, the drug can not prevent all expression of the gene and therefore the cell can restore its proliferative ability. Cancer cells can also cause defects in the cellular pathways of apoptosis (programmed cell death). As most chemotherapy drugs kill cancer cells in this manner, defective apoptosis allows survival of these cells, making them resistant. Many chemotherapy drugs also cause DNA damage, which can be repaired by enzymes in the cell that carry out DNA repair. Upregulation of these genes can overcome the DNA damage and prevent the induction of apoptosis. Mutations in genes that produce drug target proteins, such as tubulin, can occur which prevent the drugs from binding to the protein, leading to resistance to these types of drugs.[125]

Cytotoxics and targeted therapies

Targeted therapies are a relatively new class of cancer drugs that can overcome many of the issues seen with the use of cytotoxics. They are divided into two groups: small molecule and antibodies. The massive toxicity seen with the use of cytotoxics is due to the lack of cell specificity of the drugs. They will kill any rapidly dividing cell, tumor or normal. Targeted therapies are designed to affect cellular proteins or processes that are utilised by the cancer cells. This allows a high dose to cancer tissues with a relatively low dose to other tissues. As different proteins are utilised by different cancer types, the targeted therapy drugs are used on a cancer type specific, or even on a patient specific basis. Although the side effects are often less severe than that seen of cytotoxic chemotherapeutics, life-threatening effects can occur. Initially, the targeted therapeutics were supposed to be solely selective for one protein. Now it is clear that there is often a range of protein targets that the drug can bind. An example target for targeted therapy is the protein produced by the Philadelphia chromosome, a genetic lesion found commonly in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. This fusion protein has enzyme activity that can be inhibited by imatinib, a small molecule drug.[126][127][128][129]

Newer and experimental approaches

Targeted therapies

Specially targeted delivery vehicles aim to increase effective levels of chemotherapy for tumor cells while reducing effective levels for other cells. This should result in an increased tumor kill and/or reduced toxicity.[130]

Antibody-drug conjugates

Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) comprise an antibody, drug and a linker between them. The antibody will be targeted at a preferentially expressed protein in the tumour cells (known as a tumor antigen) or on cells that the tumor can utilise, such as blood vessel endothelial cells. They bind to the tumor antigen and are internalised, where the linker releases the drug into the cell. These specially targeted delivery vehicles vary in their stability, selectivity, and choice of target, but, in essence, they all aim to increase the maximum effective dose that can be delivered to the tumor cells.[131] Reduced systemic toxicity means that they can also be used in sicker patients, and that they can carry new chemotherapeutic agents that would have been far too toxic to deliver via traditional systemic approaches.

The first approved drug of this type was gemtuzumab ozogamicin (Mylotarg), released by Wyeth (now Pfizer). The drug was approved to treat acute myeloid leukemia, but has now been withdrawn from the market because the drug did not meet efficacy targets in further clinical trials.[132][133] Two other drugs, trastuzumab emtansine and brentuximab vedotin, are both in late clinical trials, and the latter has been granted accelerated approval for the treatment of refractory Hodgkins lymphoma and systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma.[131]

Nanoparticles

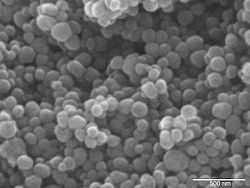

Nanoparticles are 1-1000 nanometer (nm) sized particles that can promote tumor selectivity and aid in delivering low-solubility drugs. Nanoparticles can be targeted passively or actively. Passive targeting exploits the difference between tumor blood vessels and normal blood vessels. Blood vessels in tumors are "leaky" because they have gaps from 200-2000 nm, which allow nanoparticles to escape into the tumor. Active targeting uses biological molecules (antibodies, proteins, DNA and receptor ligands) to preferentially target the nanoparticles to the tumor cells. There are many types of nanoparticle delivery systems, such as silica, polymers, liposomes and magnetic particles. Nanoparticles made of magnetic material can also be used to concentrate agents at tumor sites using an externally applied magnetic field.[130] They have emerged as a useful vehicle for poorly soluble agents such as paclitaxel.[134]

Electrochemotherapy

Electrochemotherapy is the combined treatment in which injection of a chemotherapeutic drug is followed by application of high-voltage electric pulses locally to the tumor. The treatment enables the chemotherapeutic drugs, which otherwise cannot or hardly go through the membrane of cells (such as bleomycin and cisplatin), to enter the cancer cells. Hence, greater effectiveness of antitumor treatment is achieved.

Clinical electrochemotherapy has been successfully used for treatment of cutaneous and subcutaneous tumors irrespective of their histological origin.[135][136][137][138][139][140][141] The method has been reported as safe, simple and highly effective in all reports on clinical use of electrochemotherapy. According to the ESOPE project (European Standard Operating Procedures of Electrochemotherapy), the Standard Operating Procedures (SOP) for electrochemotherapy were prepared, based on the experience of the leading European cancer centres on electrochemotherapy.[137][142] Recently, new electrochemotherapy modalities have been developed for treatment of internal tumors using surgical procedures, endoscopic routes or percutaneous approaches to gain access to the treatment area.[143][144]

Hyperthermia therapy

Hyperthermia therapy is heat treatment for cancer that can be a powerful tool when used in combination with chemotherapy (thermochemotherapy) or radiation for the control of a variety of cancers. The heat can be applied locally to the tumor site, which will dilate blood vessels to the tumor, allowing more chemotherapeutic medication to enter the tumor. Additionally, the bi-lipid layer of the tumor cell membrane will become more porous, further allowing more of the chemotherapeutic medicine to enter the tumor cell.

Hyperthermia has also been shown to help prevent or reverse "chemo-resistance." Chemotherapy resistance sometimes develops over time as the tumors adapt and can overcome the toxicity of the chemo medication. "Overcoming chemoresistance has been extensively studied within the past, especially using CDDP-resistant cells. In regard to the potential benefit that drug-resistant cells can be recruited for effective therapy by combining chemotherapy with hyperthermia, it was important to show that chemoresistance against several anticancer drugs (e.g. mitomycin C, anthracyclines, BCNU, melphalan) including CDDP could be reversed at least partially by the addition of heat.[145]

Other uses

Some chemotherapy drugs are used in diseases other than cancer, such as in autoimmune disorders,[146] and noncancerous plasma cell dyscrasia. In some cases they are often used at lower doses, which means that the side effects are minimized.[146] Methotrexate is used in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA),[147] psoriasis,[148] ankylosing spondylitis[149] and multiple sclerosis.[150][151] The anti-inflammatory response seen in RA is thought to be due to increases in adenosine, which causes immunosuppression; effects on immuno-regulatory cyclooxygenase-2 enzyme pathways; reduction in pro-inflammatory cytokines; and anti-proliferative properties.[147] Although methotrexate is used to treat both multiple sclerosis and ankylosing spondylitis, its efficacy in these diseases is still uncertain.[149][150][151] Cyclophosphamide is sometimes used to treat lupus nephritis, a common symptom of systemic lupus erythematosus.[152] Dexamethasone along with either bortezomib or melphalan is commonly used as a treatment for AL amyloidosis. Recently, bortezomid in combination with cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone has also shown promise as a treatment for AL amyloidosis. Other drugs used to treat myeloma such as lenalidomide have shown promise in treating AL amyloidosis.[153]

Chemotherapy drugs are also used in conditioning regimens prior to bone marow transplant (hematopoietic stem cell transplant). Conditioning regimens are used to suppress the recipient's immune system in order to allow a transplant to engraft. Cyclophosphamide is a common cytotoxic drug used in this manner, and is often used in conjunction with total body irradiation. Chemotherapeutic drugs may be used at high doses to permanently remove the recipient's bone marrow cells (myeloablative conditioning) or at lower doses that will prevent permanent bone marrow loss (non-myeloablative and reduced intensity conditioning).[154]

Occupational precautions

Healthcare workers exposed to antineoplastic agents take precautions to keep their exposure to a minimum. There is a limitation in cytotoxics dissolution in Australia and the United States to 20 dissolutions per pharmacist/nurse, since pharmacists who prepare these drugs or nurses who may prepare or administer them are the two occupational groups with the highest potential exposure to antineoplastic agents. In addition, physicians and operating room personnel may also be exposed through the treatment of patients. Hospital staff, such as shipping and receiving personnel, custodial workers, laundry workers, and waste handlers, all have potential exposure to these drugs during the course of their work. The increased use of antineoplastic agents in veterinary oncology also puts these workers at risk for exposure to these drugs.[155] Routes of entry into the users body are skin absorption, inhalation and ingestion. The long-term effects of exposure include chromosomal abnormalities and infertility.[156]

In other animals

Chemotherapy is used in veterinary medicine similar to how it is used in human medicine.[157]

Some of the common chemo drugs used to treat incurable diseases and cancerous tumors in animals include chlorambucil (Leukeran®), mostly in the treatment of feline infectious peritonitis (FIP); doxoribicin (Adriamycin), against lymphoma (especially in dogs); L-asparaginase, in the treatment of lymphoma (especially in dogs); and carboplatin, to treat carcinoma sarcoma (especially osteosarcoma in dogs).

Comparison of available agents

| Antineoplastic agents | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INN | Reviews | Chemical classification | Preg. cat. | Route[158] | Mechanism of action[158][159][160][161] | Indications[158][159][161] | Major toxicities[158][159][161][162] |

| 1. Cytotoxic antineoplastics | |||||||

| 1.01 Nucleoside analogues | |||||||

| Azacitidine | [163][164][165][166] [167][168][169] [170][171][172] | Cytidine analogue | X (Au) | SC, IV | DNA methyltransferase inhibitor and incorporates itself into RNA, hence inhibiting gene expression.[173] | Myelodysplastic syndromes, acute myeloid leukaemia and chronic myeloid leukaemia | Myelosuppression, kidney failure (uncommon/rare), renal tubular acidosis and hypokalaemia. |

| Capecitabine | [174][175][176] [177][178][179] [180][181][182] | Uracil analogue | D (Au) | PO | Fluorouracilprodrug | Breast, colorectal, gastric and oesophageal cancer | Myelosuppression, cardiotoxicity, hypertriglyceridaemia, GI haemorrhage (uncommon), cerebellar syndrome (uncommon), encephalopathy (uncommon) and diarrhoea. |

| Carmofur | N/A | Uracil analogue | N/A | PO | Fluorouracil prodrug | Colorectal, breast and ovarian cancer | Myelosuppression, neurotoxicity and diarrhoea. |

| Cladribine | MS: [183][184][185] [186][187][188] [189][190][191] [192] Cancer: [184][193][194] [195] | Adenosine analogue | D (Au) | PO, SC, IV | DNA methyltransferaseinhibitor, metabolites incorporate themselves into DNA.[196] | Hairy cell leukaemia, chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, Waldenstrom macroglobulinaemia and multiple sclerosis. | Myelosuppression, haemolytic anaemia (uncommon), neurotoxicity (rare), renal impairment (rare), pulmonary interstitial infiltrates (rare), Stevens-Johnson syndrome (rare) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (rare). |

| Clofarabine | [197][198][199] [200][201][202] [203][204][205] | Deoxyadenosineanalogue | D (Au) | IV | Ribonucleotide reductase and DNA polymerase inhibitor.[206] | Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia and acute myeloid leukaemia | Myelosuppression, hypokalaemia, cytokine release syndrome, Stevens-Johnson syndrome(uncommon), toxic epidermal necrolysis (uncommon) and pancreatitis (uncommon) |

| Cytarabine | [207][208][209] | Cytidine analogue | D (Au) | SC, IM, IV, IT | DNA polymerase inhibitor, S-phase specific. Incorporates its metabolites into DNA. | Acute myeloid leukaemia, acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, chronic myeloid leukaemia, lymphomas, progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy and meningeal leukaemia | Myelosuppression, GI bleeds, pancreatitis (uncommon/rare), anaphylaxis (uncommon/rare), pericarditis (uncommon/rare) and conjunctivitis (uncommon/rare). High dose: cerebral and cerebellar dysfunction, ocular toxicity, pulmonary toxicity, severe GI ulceration and peripheral neuropathy (rare). |

| Decitabine | [163][164][210] [211][212][213] [214][215][216] [217][218] | Cytidine analogue. | D (US) | IV | DNA methyltransferase inhibitor. | Myelodysplastic syndrome, sickle cell anaemia (orphan), acute myeloid leukaemia and chronic myeloid leukaemia. | Myelosuppression, hyperglycaemia, hypoalbuminaemia, hypomagnesaemia, hypokalaemia, hyperkalaemia and thrombocythaemia. |

| Floxuridine | [219] | Uracil analogue | D (US) | IA | Fluorouracil analogue. | Metastatic GI adenocarcinoma and stomach cancer | Myelosuppression. |

| Fludarabine | [220][221][222] [222][223][224] [225] | Adenosine analogue | D (Au) | PO, IV | DNA polymerase and ribonucleotide reductase inhibitor. | Acute myeloid leukaemia, chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, non-Hodgkin lymphoma and Waldenstrom macroglobulinaemia. | Myelosuppression, hyperglycaemia, GI bleeds (uncommon), pneumonitis (uncommon), haemolytic anaemia (uncommon), severe neurotoxicity (rare), haemorrhagic cystitis (rare), Stevens-Johnson syndrome (rare) and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (rare). |

| Fluorouracil | [226][227][228] | Uracil analogue | D (Au) | IV | Thymidylate synthase inhibitor. | Anal, breast, colorectal, gastric, head and neck, oesophageal and pancreatic cancer. Bowen's disease and actinic keratoses. | Myelosuppression, diarrhoea, cardiotoxicity, GI ulceration and bleeding (uncommon), cerebellar syndrome (uncommon), encephalopathy (uncommon) and anaphylaxis (rare). |

| Gemcitabine | [229][230][231] [232][233][234] [235] | Deoxycytidine analogue | D (Au) | IV | DNA synthesis inhibitor, induces apoptosis specifically in S-phase. | Bladder, breast, nasopharyngeal, non-small cell lung, ovarian and pancreatic cancer, lymphomas and inflammatory bowel disease. | Myelosuppression, pulmonary toxicity, kidney failure (rare), haemolytic uraemic syndrome(rare), thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (rare), anaphylactoid reaction (rare), reversible posterior leucoencephalopathy syndrome (rare), myocardial infarction (rare) and heart failure (rare). |

| Mercaptopurine | [236][237] | Hypoxanthine analogue | D (Au) | PO | Purine synthesis inhibitor. | Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, acute promyelocytic leukaemia, lymphoblastic lymphoma and inflammatory bowel disease.[238] | Myelosuppression, hepatotoxicity, GI ulceration (rare), pancreatitis (rare) and secondary leukaemia (rare) or myelodysplasia (rare). |

| Nelarabine[239] | [240][241] [242][243][244] [245][246] | Adenosine analogue | D (US) | IV | Purine synthesis inhibitor. | Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia and chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. | Myelosuppression, pleural effusion, seizures, tumour lysis syndrome and a condition similar to Guillain-Barré syndrome. |

| Pentostatin | [247][248][249] [250][251][252] | Adenosine analogue | D (US) | IV | Adenosine deaminase inhibitor. | Hairy cell leukaemia, peripheral T-cell lymphoma (orphan), cutaneous T cell lymphoma (orphan) and chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (orphan). | Myelosuppression, neurotoxicity, immune hypersensitivity, hyponatraemia, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and microangiopathic hemolytic anaemia. |

| Tegafur | [253][254][255] [256][257][258] [259] | Fluorouracilanalogue | D (Au) | PO | Thymidylate synthase inhibitor. | Breast, colorectal cancer, gallbladder, gastrointestinal tract, head and neck, liver and pancreas cancer. | Myelosuppression, diarrhoea, neurotoxicity and hepatitis (rare). |

| Tioguanine | [260][261][262] [263][264] | Guanine analogue. | D (Au) | PO | Purine synthesis inhibitor. | Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia and acute myeloid leukaemia | Myelosuppression, hepatotoxicity, peripheral neuropathy (uncommon), intestinal necrosis (rare) and perforation (rare). |

| 1.02 Antifolates | |||||||

| Methotrexate | [265][266][267] [268][269][270] | Folate analogue | D (Au) | SC, IM, IV, IT, PO | Dihydrofolate reductase inhibitor. | Bladder and breast cancer. squamous cell carcinoma of head and neck, gestational trophoblastic disease, acute leukaemias, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, osteosarcoma, brain tumours, graft-versus-host disease and systemic sclerosis. | Myelosuppression, pulmonary toxicity, hepatotoxicity, neurotoxicity (high dose or intrathecal administration), anaphylactic reactions (rare), Stevens-Johnson syndrome (rare), Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (rare), kidney failure (rare), osteoporosis (rare), skin and bone necrosis (rare) and macrocytic anaemia (rare). |

| Pemetrexed | [271][272][273] [274][275][276] [277][278] [279][280][281] [282][282][283] [284][285][286] [287][288][289] [290][291][292] [293][294][295] | Folate analogue | D (Au) | IV | Dihydrofolate reductase, thymidylate synthase and glycinamide ribonucleotide formyltransferase inhibitors. | Malignant mesothelioma and non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer. | Myelosuppression, renal impairment, peripheral neuropathy, Supraventricular tachycardia (uncommon), hepatitis (rare), colitis (rare), pneumonitis (rare), radiation recall (rare), Stevens-Johnson syndrome (rare) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (rare). |

| Raltitrexed | [296][297][298] [298][299][300] [301][302] | Quinazolinone | D (Au) | IV | Dihydrofolate reductase and thymidylate synthase inhibitor. | Colorectal cancer | Myelosuppression |

| 1.03 Other antimetabolites | |||||||

| Hydroxycarbamide | [303][304][305] [306][307][308] [309][310][311] [312] | Urea analogue | D (Au) | PO | Inhibits DNA synthesis by inhibiting the enzyme ribonucleotide reductase. | Chronic myeloid leukaemia, essential thrombocytosis, polycythaemia vera, myelofibrosis, acute myeloid leukaemia and sickle cell anaemia | Myelosuppression, skin cancer (rare), oedema (rare), hallucinations (rare), seizures (rare) and pulmonary toxicity (rare). |

| 1.04 Topoisomerase I inhibitor | |||||||

| Irinotecan | Camptothecin | D (Au) | IV | Inhibits topoisomerase I. | Colorectal cancer | Diarrhoea, myelosuppression, pulmonary infiltrates (uncommon), bradycardia (uncommon), ileus (rare) and colitis (rare). | |

| Topotecan | Camptothecin | D (Au) | IV | Inhibits topoisomerase I. | Small cell lung cancer, ovarian cancer and cervical cancer | Diarrhoea, myelosuppression, interstitial lung disease and allergy. | |

| 1.05 Anthracyclines | |||||||

| Daunorubicin | Anthracycline | D (Au) | IV | Inhibits DNA and RNA synthesis by intercalating DNA base pairs. Inhibits DNA repair by inhibiting topoisomerase II. | Acute leukaemias | Myelosuppression, cardiotoxicity, anaphylaxis (rare), secondary malignancies (particularly acute myeloid leukaemia and myelodysplastic syndrome) and radiation recall. | |

| Doxorubicin | Anthracycline | D (Au) | IV | As above. | Breast cancer, lymphomas, sarcomas, bladder cancer, acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, Wilms' tumour, AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma, neuroblastoma and multiple myeloma | As above. | |

| Epirubicin | Anthracycline | D (Au) | IV | As above. | Breast cancer, gastric cancer and bladder cancer | As above. | |

| Idarubicin | Anthracycline | D (Au) | IV, PO | As above. | Acute leukaemias. | As above. | |

| Mitoxantrone | Anthracenedione | D (Au) | IV | As above. | Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, acute myeloid leukaemia, prostate cancer and multiple sclerosis | As above. | |

| Valrubicin | Anthracycline | C (US) | IV | As above. | Bladder cancer. | As above. | |

| 1.06 Podophyllotoxins | |||||||

| Etoposide | Podophyllotoxin | D (Au) | IV, PO | Topoisomerase II inhibitor. | Testicular cancer, ovarian cancer, lung cancer, acute myeloid leukaemia, lymphomas and sarcomas | Myelosuppression, hypersensitivity reactions, Stevens-Johnson syndrome (rare), peripheral neuropathy (uncommon) and secondary malignancies (especially acute myeloid leukaemia). | |

| Teniposide | Podophyllotoxin | D (Au) | IV | Topoisomerase II inhibitor. | Lymphomas, acute lymphoblastic leukaemia and neuroblastoma | As above. | |

| 1.07 Taxanes | |||||||

| Cabazitaxel | Taxane | D (Au) | IV | Microtubule disassembly inhibitor. Arrests cells in late G2 phase and M phase. | Prostate cancer | Myelosuppression, diarrhoea, kidney failure, hypersensitivity, severe GI reactions (including perforation, ileus, colitis, etc.; all rare) and peripheral neuropathy | |

| Docetaxel | Taxane | D (Au) | IV | As above. | Breast cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, ovarian cancer, prostate cancer, squamous cell head and neck cancer and gastric cancer. | Myelosuppression, peripheral neuropathy, hypersensitivity, fluid retention, heart failure (uncommon), pulmonary toxicity (rare), radiation recall (rare), scleroderma-like skin changes (rare), Stevens-Johnson syndrome (rare), toxic epidermal necrolysis (rare), seizures (rare) and encephalopathy (rare) | |

| Paclitaxel | Taxane | D (Au) | IV | As above. | Ovarian cancer, breast cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma, cervical cancer, germ cell cancer and endometrial cancer | Hypersensitivity, myelosuppression, peripheral neuropathy, myocardial infarction (uncommon), arrhythmias (uncommon), pulmonary toxicity (rare), radiation recall (rare), scleroderma-like skin changes (rare), Stevens-Johnson syndrome (rare), toxic epidermal necrolysis (rare), seizures (rare) and encephalopathy (rare). | |

| 1.08 Vinca alkaloids | |||||||

| Vinblastine | Vinca alkaloid | D (Au) | IV | Microtubule assembly inhibitor. Arrests cells in M phase. | Hodgkin lymphoma, germ cell tumours, non-small cell lung cancer, bladder cancer and primary immune thrombocytopenia | Neurotoxicity, myelosuppression, myocardial ischaemia (rare) and myocardial infarction (rare). | |

| Vincristine | Vinca alkaloid | D (Au) | IV | As above. | Lymphomas, acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, multiple myeloma, sarcoma, brain tumours, Wilms' tumour, neuroblastoma and primary immune thrombocytopenia | Neurotoxicity, anaphylaxis (rare), myocardial ischaemia (rare) and myocardial infarction (rare). | |

| Vindesine | Vinka alkaloid | D (Au) | IV | As above. | Refractory metastatic melanoma, childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, chronic myeloid leukaemia in blast crises, neuroblastoma, non-small cell lung cancer and breast cancer. | Myelosuppression, neurotoxicity and paralytic ileus. | |

| Vinflunine | Vinca alkaloid | D (Au) | IV | As above. | Bladder cancer | As per vinblastine. | |

| Vinorelbine | Vinca alkaloid | D (Au) | IV | As above. | Breast cancer and non-small cell lung cancer. | As above. | |

| 1.09 Alkylating agents | |||||||

| Bendamustine | Nitrogen mustard | D (Au) | IV | Alkylates DNA. | Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, mantle cell lymphoma and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. | Myelosuppression, hypokalaemia and tachycardia. | |

| Busulfan | Dialkylsulfonate | D (Au) | IV, PO | Alkylates DNA. | Conditioning treatment before haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (high dose, IV), chronic myeloid leukaemia, myelofibrosis, polycythaemia vera and essential thrombocytosis | Myelosuppression, seizures (high dose), tachycardia (high dose), hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (high dose), Addison-like syndrome (rare), pulmonary fibrosis (rare), cataracts (rare) and hepatitis (rare). Secondary malignancies.[158][313] | |

| Carmustine | Nitrosourea | D (Au) | IV | Alkylates DNA. | Anaplastic astrocytoma, glioblastoma multiforme and mycosis fungoides (topical) | Myelosuppression, pulmonary fibrosis, pulmonary infiltrates, seizure, brain oedema, cerebrospinal leaks, subdural fluid collection, intracranial infection, hypotension (uncommon), tachycardia (uncommon), decrease in kidney size (reversible), uraemia (uncommon), kidney failure (uncommon), severe hepatic toxicity (rare), thrombosis (rare) and neuroretinitis (rare). Secondary malignancies.[158][313] | |

| Chlorambucil | Nitrogen mustard | D (Au) | IV | Alkylates DNA. | Lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukaemia and Waldenström's macroglobulinaemia | Myelosuppression, hallucinations (rare), seizures (rare), sterile cystitis (rare), hepatotoxicity (rare), severe pneumonitis (rare), Stevens-Johnson syndrome (rare), toxic epidermal necrolysis (rare) and drug fever (rare). Secondary malignancies.[158][313] | |

| Chlormethine | Nitrogen mustard | D (Au) | IV, topical | Alkylates DNA. | Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma, metastatic carcinoma, leukaemias, lymphomas, polycythemia vera and bronchogenic carcinoma | Thrombosis, myelosuppression (common), hyperuricaemia, erythema multiforme, haemolytic anaemia, nausea and vomiting (severe) and secondary malignancies.[313] | |

| Cyclophosphamide | Nitrogen mustard | D (Au) | IV | Alkylates DNA. | Breast cancer, lymphoma, acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, sarcoma, multiple myeloma, Waldenström's macroglobulinaemia, systemic lupus erythematosus, glomerulonephritis, systemic vasculitis and Wegener's granulomatosis | Myelosuppression, nausea and vomiting (>30%), haemorrhagic cystitis, heart failure (rare), pulmonary fibrosis (rare), hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (rare), water retention resembling SIADH (rare) and seizures (rare). Secondary malignancies.[313] | |

| Dacarbazine | Triazene | D (Au) | IV | Alkylates DNA. | Hodgkin lymphoma, metastatic malignant melanoma and soft tissue sarcoma | Myelosuppression, agranulocytosis (uncommon), hepatic vein thrombosis (rare) and hepatocellular necrosis (rare). Secondary malignancies.[313] | |

| Fotemustine | Nitrosourea | D (Au) | IV | Alkylates DNA. | Metastatic malignant melanoma. | Myelosuppression. | |

| Ifosfamide | Nitrogen mustard | D (Au) | IV | Alkylates DNA. | Sarcomas, testicular cancer and lymphomas. | Myelosuppression, haemorrhagic cystitis, nephrotoxicity, neurotoxicity and cardiac toxicity (rare). Secondary malignancies.[313] | |

| Lomustine | Nitrosourea | D (Au) | PO | Alkylates DNA. | Glioma and medulloblastoma. | Myelosuppression, pulmonary infiltration and fibrosis. Secondary malignancies.[313] | |

| Melphalan | Nitrogen mustard | D (Au) | IV, PO | Alkylates DNA. | Malignant melanoma of the extremities, multiple myeloma, conditioning treatment before haemopoietic stem cell transplant. | Myelosuppression, pulmonary fibrosis and pneumonitis (uncommon), skin necrosis (uncommon), anaphylaxis, hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome and SIADH. Secondary malignancies.[313] | |

| Streptozotocin | Nitrosourea | D (Au) | IV, PO | Alkylates DNA. | Pancreatic cancer and carcinoid syndrome. | Nephrotoxicity, hypoglycaemia, myelosuppression, nausea and vomiting (>90%), jaundice and nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (rare). | |

| Temozolomide | Triazene | D (US) | PO | Alkylates DNA. | Anaplastic astrocytoma, glioblastoma multiforme, metastatic malignant melanoma | Myelosuppression, Stevens-Johnson syndrome (rare), pneumonitis (rare) and hepatitis (rare). | |

| 1.10 Platinum compounds | |||||||

| Carboplatin | Platinum complex | D (Au) | IV | Reacts with DNA, inducing apoptosis, non-cell cycle specific. | Ovarian cancer, lung cancer and squamous cell head and neck cancer | Myelosuppression, nausea and vomiting (30-90%), peripheral neuropathy, ototoxicity, anaphylaxis, acute kidney failure (rare), haemolytic uraemic syndrome (rare) and loss of vision (rare). | |

| Cisplatin | Platinum complex | D (Au) | IV | As above. | Germ cell tumours (including testicular cancer), ovarian cancer, cervical cancer, small cell and non-small cell lung cancer, mesothelioma, squamous cell head and neck cancer, oesophageal cancer, gastric cancer, bladder cancer and osteosarcoma | Nephrotoxicity, nausea and vomiting (30-100%), myelosuppression, electrolyte anomalies, peripheral neuropathy, ototoxicity and anaphylaxis, haemolytic anaemia (rare), optic neuritis (rare), reversible posterior leucoencephalopathy syndrome (rare), seizures (rare), ECG changes (rare) and heart failure (rare). | |

| Nedaplatin | [314] | Platinum complex | N/A | IV | As above. | Non-small cell lung cancer, oesophageal cancer, uterine cervical cancer, head and neck cancer and urothelial cancer | Nephrotoxicity, myelosuppression and nausea and vomiting (30-90%). |

| Oxaliplatin | Platinum complex | D (Au) | IV | As above. | Colorectal cancer, oesophageal cancer and gastric cancer | Myelosuppression, peripheral neuropathy, anaphylaxis, nausea and vomiting (30-90%), hypokalaemia, metabolic acidosis, interstitial lung disease (uncommon), ototoxicity (rare), reversible posterior leucoencephalopathy syndrome (rare), immune-mediated cytopenias (rare) and hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (rare). | |

| 1.11 Miscellaneous others | |||||||

| Altretamine | Triazine | D (Au) | PO | Unclear, reactive intermediates covalently bind to microsomal proteins and DNA, possibly causing DNA damage | Recurrent ovarian cancer | Myelosuppression, peripheral neuropathy, seizures and hepatotoxicity (rare). | |

| Bleomycin | Glycopeptide | D (Au) | IM, SC, IA, IV or IP | Inhibits DNA and to a lesser extent RNA synthesis, produces single and double strand breaks in DNA possibly by free radical formation. | Germ cell tumours, squamous cell carcinoma, pancreatic cancer, non-Hodgkin's, pleural sclerosing and Hodgkin's lymphoma. | Pulmonary toxicity, hypersensitivity, scleroderma and Raynaud's phenomenon. | |

| Bortezomib | Dipeptidyl boronic acid | C (Au) | IV, SC | Proteasome inhibitor. | Multiple myeloma, mantle cell lymphoma and follicular lymphoma (orphan). | Peripheral neuropathy, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, anaemia, orthostatic hypotension, hepatitis (uncommon/rare), haemorrhage (uncommon/rare), heart failure (uncommon/rare), seizures (uncommon/rare), progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy (PML) and hearing loss. | |

| Dactinomycin | Polypeptide | D (Au) | IV | Complexes with DNA interfering with DNA-dependent RNA synthesis | Gestational trophoblastic disease, Wilms' tumour and rhabdomyosarcoma | Myelosuppression, anaphylaxis, radiation recall, hepatotoxicity and hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (common in Wilms' tumour). | |

| Estramustine | Nitrogen mustard and oestrogen analogue | D (Au) | PO | Antimicrotubule and oestrogenic actions | Prostate cancer. | Cardiovascular complications, such as ischaemic heart disease, venous thromboembolism, congestive heart failure, pulmonary embolism, myocardial infarction and cerebrovascular failure. | |

| Ixabepilone | Epothilone B analogue | D (US) | IV | Promotes tubulin polymerisation and stabilises microtubular function, causing cell cycle arrest at G2/M phase and subsequently induces apoptosis | Locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer. | Myelosuppression, peripheral neuropathy, myocardial ischaemia (uncommon/rare), supraventricular arrhythmia (uncommon/rare) and hypersensitivity reaction (uncommon/rare). | |

| Mitomycin | Aziridine | D (Au) | IV | Cross-links DNA | Anal and bladder cancer | Myelosuppression, pulmonary toxicity and haemolytic uraemic syndrome (rare). | |

| Procarbazine | Methylhydrazine | D (Au) | IM, IV | Inhibits DNA, RNA and protein synthesis. | Glioma and Hodgkin's lymphoma. | Myelosuppression, neurotoxicity, pulmonary fibrosis (uncommon/rare), pneumonitis (uncommon/rare), haemolysis (uncommon/rare) and hepatic dysfunction (uncommon/rare). | |

| 2. Targeted antineoplastics | |||||||

| 2.1 Monoclonal antibodies | |||||||

| Alemtuzumab | Protein | B2 (Au) | IV | CD52 antibody induces apoptosis in the tagged cells. | Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia | Pancytopenia, pneumonitis, arrhythmias and hypersensitivity reactions (rare), autoimmune haemolytic anaemia (rare), autoimmune thrombocytopenia (rare) and progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy (rare). | |