Chemins de Fer du Calvados

| Chemins de Fer du Calvados | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Legend

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

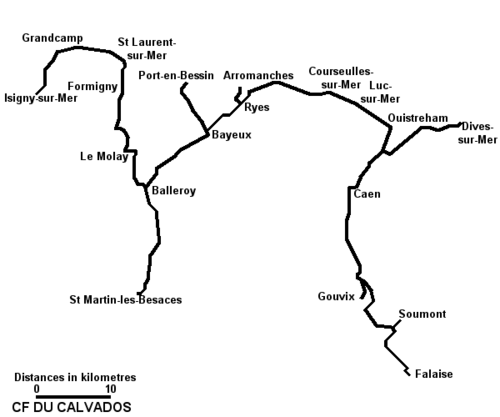

The Chemins de Fer du Calvados was a 600 mm (1 ft 11 5⁄8 in) narrow gauge railway in the département of Calvados.

History

The Chemins de Fer du Calvados (CFC) was originally planned as a 1,000 mm (3 ft 3 3⁄8 in) metre gauge line. The département had actually accepted a tender for the construction of such a line but with interest in 600 mm (1 ft 11 5⁄8 in) narrow gauge lines rising the département had a rethink and the line was built to 600 mm gauge.[1]

Paul Decauville was approached following his success at the Paris Exhibition. In October 1890 he was asked to build a line on a similar basis to that already under construction at Royan. Initially, two separate lines were envisaged. A 29 kilometres (18 mi) line between Dives and Luc-sur-Mer and a 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) line between Isigny and Grandcamp-le-Château.[1]

Ouistreham – Luc-sur-Mer opened to traffic on 15 August 1891, with an official opening date of 15 October. Dives – Sallenelles opened to traffic on 15 July 1892 and Sallenelles – Ouistreham opened on 24 August, following completion of swing bridges at Ranville and Bénouville. The former was designed by Gustave Eiffel.[1] The latter was to become famous as Pegasus Bridge.[2]

Bénouville – Caen opened to traffic on 4 July 1893, having been held up by the financial situation of the Société Decauville. The construction of the Isigny – Grandcamp line was delayed for this reason too.[1]

With the demise of Decauville, the Société Anonyme des Chemins de Fer Du Calvados (CFC) took over the lines on 1 August 1895. The CFC used rails laid on wooden sleepers, and Westinghouse continuous braking, quite an advanced piece of technology on such a small gauge.[1] Decauville referred to the line as the Tramway du Calvados but the new company were quite sure that they were running a railway, offering 1st, 2nd and 3rd class accommodation on its trains.[2]

Isigny – Grandcamp-les-Bains opened to traffic on 27 July 1896. On 15 June 1897, authorisation was given for more lines to be constructed in the Calvados département:- a 32 kilometres (20 mi) line between Grandcamp and Le-Morlay-Littry; a 26 kilometres (16 mi) line between Corseulles and Bayeux, with a branch to Arromanches-les-Bains; a 45 kilometres (28 mi) line between Caen and Falaise; and an 11 kilometres (6.8 mi) line between Bayeux and Port-en-Bessin. These lines opened between 1899 and 1902.[1]

On 18 January 1904, a short extension opened between Falaise-Château and Falaise Gare, connecting with the standard gauge main line. Between 1904 and 1906 further extensions were added, a 9.5 kilometres (5.9 mi) line between Molay de Littry and Balleroy, and a 40.5 kilometres (25.2 mi) line between Bayeux and St. Martin-les-Besaces.[1]

This left two isolated systems, which were joined by laying a dual gauge track on the standard gauge Chemin de Fer de Caen à la Mer for 8 kilometres (5.0 mi) between Luc-sur-Mer and Courseulles, with a passing loop at St. Aubin-sur-Mer. This link opened to traffic on 1 July 1900.[1] Because of the terms provided in the agreement allowing the construction of the link, it was mainly used for the transfer of stock between each part of the system, which was in effect run as two separate systems.[2] The CFC had a total extent of 234 kilometres (145 mi). There were plans to add a further 369 kilometres (229 mi) of lines, but these plans were abandoned due to improvements in the road system in the département and the extensive network of standard gauge lines.[1]

The CFC hoped to benefit from transporting coal. Mines at Littry had been in operation from 1743 to 1880, when they were closed due to flooding. There were frequent proposals to reopen the mine, but it was not until 1941 that an exploratory pit was opened by the Société Métallurgique de Normandie. Full production started in 1945, by which time the CFC had closed and finished in 1950.[2]

Another source of traffic for the CFC was iron ore deposits between Caen and Falaise. Long sidings were laid to enable the transport of iron ore to the blast furnaces at Caen, which was developed c1910 by the Société des Hauts-Fourneaux de Caen, which later became the Société Métallurgique de Normandie (SMN). Three thousand tonnes of ore were required per day, which the CFC handled, would have meant thirty trains per day. The Chemin de Fer du Nord proposed a standard gauge line to carry the traffic. The CFC argued that they could carry all the traffic and proposed to double the line south of Caen, but later decided against this. The CFC agreed to handle 25% of the traffic and accept compensation of 35 centimes per tonne carried by the SMN for "lost" revenue. This compensation continued to be paid after the line south of Caen closed.[2][3]

The coastal routes provided the CFC with good returns but the inland routes did not. Despite the introduction of railcars in the 1920s, the line from Isigny to Balleroy closed on 2 December 1929. The rails were lifted c.1933. and the stations sold to be converted to dwellings. Vierville station was burned down on 7 June 1944 during the D-Day landings.[4] The lines from Bayeux closed between 1930 and 1933, and the section south of Caen closed in 1930. The line between Bénouville and Dives closed in 1932 as the swing bridge needed replacement and it wasn't thought viable to lay tracks on the new bridge.[1]

This left just the Caen – Luc-sur-Mer line open after 1932, operating a summer only service. There was a proposal to convert the line to metre gauge and electrify it at 1500V. With the introduction of paid holidays for French workers in 1936, the line saw a large increase in passenger numbers. The line was transferred to the Société des Courriers Normands, which was primarily a bus company, in 1937.[2] Following the outbreak of World War Two in 1939, an all year round service was reinstated. The line closed on 6 June 1944, after the track was destroyed during the D-Day landings. The first train of the day, hauled by No. 10, was abandoned at Luc-sur-Mer, never to complete its journey.[1][2]

Construction

The first lines built, linking Caen with the coast used 15 kg/m rails. The loading gauge allowed a width of 1.88 metres (6 ft 2 in) and height of 2.80 metres (9 ft 2 in). Gradients were to be no steeper than 30mm/m (1 in 33). Trains were to be restricted to 20 kilometres per hour (12 mph) with a maximum length of 60 metres (200 ft). Later lines were built with rails of 18 or 20 kg/m and the earlier lines were upgraded in the 1930s. Many of the lines were laid alongside roads or canals. [2]

Line openings

| Opened | Section | Length (km) | Closed |

| Luc-sur-Mer – Dives-sur-Mer | |||

| 1891 | Luc-sur-Mer – Ouistreham | 9 | 1944 |

| 1892 | Ouistreham – Bénouville | 4 | 1944 |

| 1892 | Bénouville – Dives-sur-Mer | 15 | 1932 |

| Luc-sur-Mer – Bayeux | |||

| 1900 | Luc-sur-Mer – Courseulles-sur-Mer (addition of a third track onto the track of the CF de Caen à la Mer) | 8 | 1931 |

| 1899 | Courseulles-sur-Mer – Bayeux | 22 | 1931 |

| 1899 | Ryes – Arromanches | 4 | 1930 |

| Bénouville – Caen | |||

| 1893 | Bénouville – Caen Saint-Pierre | 10 | 1944 |

| 1904 | Caen Saint-Pierre – Caen Ouest | 2 | 1944 |

| Isigny-sur-Mer – Balleroy | |||

| 1896 | Isigny-sur-Mer – Grandcamp | 10 | 1929 |

| 1900 | Grandcamp – Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer | 12 | 1929 |

| 1901 | Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer – La mine de Littry | 20 | 1929 |

| 1904 | La mine de Littry – Balleroy | 9 | 1929 |

| Port-en-Bessin – Saint-Martin-des-Besaces | |||

| 1899 | Bayeux – Port-en-Bessin | 11 | 1932 |

| 1904 | Bayeux – Balleroy | 16 | 1930 |

| 1906 | Balleroy – Saint-Martin-des-Besaces | 25 | 1930 |

| Caen – Falaise | |||

| 1902 | Caen Ouest – Potigny | 32 | 1933 |

| 1902 | Potigny – Falaise Château | 12 | 1932 |

| 1904 | Falaise Château – Falaise | 2 | 1932 |

Network

Accidents

On one occasion, the driver of a train failed to see that Pegasus Bridge was open, and the locomotive went over the edge into the Orne, fortunately without serious damage or injury.[2]

Rolling stock

The CFC operated the following rolling stock.[1]

Locomotives

- Three 0-4-4-0T Mallets built by Société Anonyme la Métallurgique, (Tubize), ex Paris Exhibition, transferred from the Tramways de Royan in 1891. Sold by 1908

- Four 0-4-4-0T Mallets, built by Decauville, in 1892 and 1893. Sold by 1908. One of these was work number 110/1891. Named Luc-sur-Mer until 1896 then Grandcamp and carried number 7. Sold to the Tramway de Pithiviers à Toury in 1908.[5]

- 0-6-2T built by Decauville (system Weidknecht), works number 128/1891. Carried number 7, named Hermanville[5] Sold to C Besse, Sablieres, Darvault by 1893.[6]

- 0-6-0T built by Ateliers du Nord de la France, (Blanc-Misseron), for Decauville in 1895. Carried the name Isigny[2]

- Six 0-6-0TR Bi-cabine built by Blanc-Misseron for Tubize in 1899 and 1900.

- Two 0-6-4TR Bi-cabine built by Blanc-Misseron in 1901.

- Six 4-6-0T built by Weidknecht between 1902 and 1909. Numbered 9–14.[2]

- Ten 4-6-0-TR Bi-cabine built by Blanc-Misseron for Tubize between 1902 and 1909. One was numbered 106.

- Three 0-6-2TR Bi-cabine built by Tubize in 1913.

- Decauville 0-6-2T (Systeme Weidknecht) works number 549/1893 Ville de Caen,[6] acquired second hand in 1908. Carried number 7. Later rebuilt as 0-6-4T[2]

Railcars

- Three Crochat four wheel railcars, supplied in 1925. Powered by 30 horsepower (22 kW) Aster petrol engines. Numbered AU1-3. One preserved at the Musée des Transports de Pithiviers.[2]

- Two Decauville railcars, ex Savoie lines, acquired second hand in 1936. Numbered DC11 and 12. Sold to the Tramway de Pithiviers à Toury before the closure of the CFC.[2]

Passenger stock

The CFC had the following passenger stock.[1][2]

- Decauville KE, KG and IS type bogie carriages. These carriages were 1st/2nd, 2nd/3rd and all 3rd. There was one carriage from the Paris Exposition which was furnished with a bar. It was later converted to a 1st/2nd railcar trailer. The KE type coaches were originally all open, but later acquired glass end screens.

- Eighty Belgian built four wheel coaches. These were 6 metres (19 ft 8 in) long on a 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) wheelbase. They were classed as A (all 1st), AB (1st/2nd), AD (1st)/fourgon, B (all 2nd), C (all 3rd) and CD (3rd/fourgon). The closed vehicles seated 16 with 8 standing, and those with open sides seated 24.

- Two bogie Fourgons built by Decauville.

- Two bicycle carriers built by Decauville.

Freight stock

The CFC operated the following freight stock.[1][2]

Four wheeled open wagons and closed vans, with a capacity of 10 tonnes, but restricted to 7 tonnes on the lines laid with the lighter rails. also ten bogie lowside wagons by Decauville. There were some unsprung, dumb buffered ballast wagons and some bogie flat wagons. There were two couverts surbaissés, which were low floor bogie wagons for conveying cattle or horses. For mineral traffic four wheeled steel sided dropside open wagons were used. Some had brake-huts. There were also ten bogie opens. Another fifty bogie wagons were ordered by the Mines de Barbery in 1914, but it is not known if these were delivered.

Architecture

A sense of identity

As many railway companies, Calvados adopted its own architecture. Due to relative small size of the company, despite its large network, the company never built large stations. Instead, Calvados built small but efficient and practical buildings in a mock Norman style.

Calvados built stations in a range of sizes, some being nothing more than a bus shelter, others fully functional railway stations, similar to Ouest BV5 stations.

Station photos

-

Panorama halt

-

Le Home-Varaville station

-

Courseulles-sur-Mer station

-

Caen St. Pierre station

The line today

Station buildings survive at Luc-sur-Mer, which is used by the local Gendarmerie. St. Aubin, which is used as a bus station. Bernières-sur-Mer, which is used as the local tourist office. St. Côme and Sommervieu are private dwellings. Arromanches is used as a bus terminus. Bayeux station building also survives and is used as offices by a bus company.[2] St. Laurence Englesqueville station survives, converted to a dwelling.[4]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 Organ, John (2002). Northern France Narrow Gauge. Midhurst: Middleton Press. ISBN 1-901706-75-3.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 "UN P'TIT CALVA". Andy Hart/SNCF Society. Archived from the original on 30 October 2007. Retrieved 2008-02-21.

- ↑ "Les hauts-fourneaux de Caen". Normannia. Retrieved 2008-02-21. (fr)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Les "carosses", le tramway, puis les Courriers Normands". Vierville-sur-Mer. Retrieved 2008-02-21.(fr)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "The Industrial Railway Record". Industrial Railway Society. Retrieved 2008-02-21.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Davies, W J K (February 2008). "Standard Decauville Stock". Continental Modeller 30 (2): 88–91. ISSN 0955-1298.