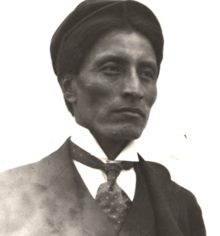

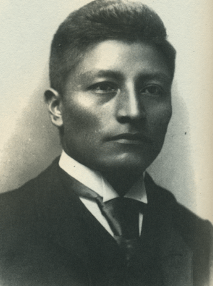

Chauncey Yellow Robe

| Chauncey Yellow Robe Canowicakte ("Kills in the Woods") | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chauncey Yellow Robe | |

| Sicangu Lakota leader | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1867 |

| Died | 1930 (age 63) |

| Spouse(s) | Lillian Belle Springer |

| Children | Rosebud (daughter) Chauncina (daughter) Evelyn (daughter) |

| Parents | Chief Yellow Robe (Tasinagi) (father) Tachcawin (Deer Woman) (mother) |

| Known for | Educator, lecturer and activist |

| Nickname(s) | Timber and Chano |

Chauncey Yellow Robe ("Kills in the Woods") (Canowicakte) (1867–1930) was an educator, lecturer and Native American activist. Yellow Robe was a widely known intellectual and one of the best-educated American Indians in the United States. Yellow Robe was raised in the Sicangu Lakota tradition, an honors graduate of the Carlisle Indian School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, and a founding member of the Society of American Indians. He crossed cultural bridges to improve the status of American Indians, believed that the majority of Anglos were ignorant of what Indians were capable of achieving, and urged Indians to fully participate in all aspects of American life. Yellow Robe was at the forefront in the fight for American Indian citizenship during the Progressive Era, and collaborated with American Museum of Natural History to produce The Silent Enemy, the first movie and documentary with an all-Indian cast.

Early life

Chauncey Yellow Robe ("Kills in the Woods") (Canowicakte) was born in what is now southern Montana around 1867, in the Sičháŋǧu Oyáte in Lakota or "Burnt Thighs Nation." [1] Chauncey’s father Chief Yellow Robe (Tasinagi), first known as White Thunder, assumed the name Yellow Robe name for his heroic war deeds against a Yellow Robe family of Crow Indians. Tasinagi was a descendant of two famous leaders of the Dakota Sioux nation, Sitting Bull and Iron Plume. Tasinagi signed the Treaty of 1868, fought in the Battle of the Little Big Horn and died in 1904 at the age of eighty-seven,[2] Chauncey’s mother Tachcawin (Deer Woman), was a niece of Sitting Bull and had seven children with Chief Yellow Robe.[3] As a boy, Chauncey lived on the Rosebud Indian Reservation. "Kills in the Woods" was trained in Lakota skills of making bows and arrows, riding ponies bareback, foot racing, wrestling and swimming.[4] “Sometimes during a morning of a winter blizzard my father used to wake me up out of my warm bed of buffalo robes and dare me to go out and lay down in the deep snow and roll in it ‘as I had come into the world'. This was not as a punishment, but a test of endurance.”[5] Chauncey did not see a white man until he was ten or eleven years old. When he did, he could not decide if it was a man or an animal, and as the creature approached, he decided it was an evil spirit and ran to the tipi of his father.[6] “Canowicakte spent many hours in the tipi of his grandfather and grandmother. They were his tutors in legends and history of the tribe. He was expected to memorize all these stories so that he in turn would be able to relate them to his children. He was taught respect and reverence for Wakan-tanka, the Great Mystery. He learned of the great and inspiring deeds of the famous chiefs, warriors and medicine men. He was trained in the old customs of how to make bows and arrows for hunting and for wars. He learned how to hunt deer and buffalo. He enjoyed wrestling, swimming and foot racing with his companions." [7] Later in his life, Chauncey would spend many hours telling his children the Lakota tales he was told by his grandparents.

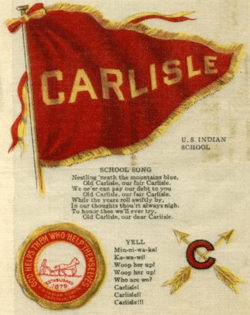

Carlisle Indian School

Chief Yellow Robe sent two sons to the Carlisle Indian School, Kills in the Woods (Chauncey) and younger brother Search the Enemy (Richard). Carlisle classmates nicknamed the brothers “Wounded” and “Timber”.[8] Chauncey and Richard were about 12–15 years old when they arrived on November 20, 1883, to enter Carlisle’s fourth class.[9] The first six months at Carlisle were the saddest of Chancey’s life as he tried to accustom himself to the new and strange environment.[10] He wrote, “Never had I experienced such homesickness as I did then. How many times have I watched the western sky and cried within my broken heart, wishing to see my father and mother again and be free on the plains.”[11] But he recalled his mother’s admonition: “Go, and like a warrior, be brave, remembering always your people and their great need of you.” [12] Chauncey did not yet know English and was confused about the abrupt departure from his own culture. His braids were cut and his traditional clothing replaced with a white man's suit.[13] In 1890, Captain Richard Henry Pratt, sent Yellow Robe to Washington DC to serve as an interpreter at an inquiry made by the Office of Indian Affairs into the treatment of Indians traveling with Buffalo Bill’s show. Acting Commissioner Belt said of Chauncey: “We thank you for sending so capable an interpreter as Yellow Robe was found to be.”[14]

Chauncey recognized then the extent to which his people were being exploited and sensationalized, and it kindled a lifelong antipathy for theatrical performances.[15] Chauncey soon became one of Captain Pratt's model Carlisle students. Both Pratt and Chauncey were ardent fishermen, and they spent summer days together with rod and line.[16] Like many other Carlisle students, Chauncey had high personal regard for Captain Pratt, their “school father.”[17] Carlisle gave its students opportunities to interact and live in the Anglo world. The Carlisle Summer Outing Program arranged for students to work in homes as domestic servants or in farms or businesses during the summer, for which they earned their first wages.[18] Chauncey’s first experience with the outing program took place during his second summer with a Quaker farmer. Later, Chauncey’s summers were spent working on farms, attending the Moody Summer School at Northfield, Massachusetts, and serving as an athletic instructor at resorts along the Atlantic seacoast.[19]

In 1893, Pratt chose Yellow Robe as a representative of North American Indians at the Congress of Nations at the opening of the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Illinois. In 1895, after twelve years of study at the Carlisle Indian School, Chauncey Yellow Robe graduated with honors.[20]

Government service

In 1885, Yellow Robe returned to Rosebud after completing his studies in Carlisle. After first considering entering the ministry, he entered the Bureau of Indian Affairs school system and worked at a number of locations including Santee, Nebraska, Genoa, Nebraska, and Fort Lewis, Colorado. In 1897, he was appointed boys’ disciplinarian at Fort Shaw Indian School in Montana.[21] In 1898, Chauncey returned to Carlisle as assistant disciplinarian, and then back to Fort Shaw, Montana.[22] In 1905, Yellow Robe entered the Rapid City Indian School in Rapid City, South Dakota, and remained there for the next twenty-three years, serving as a teacher, disciplinarian and basketball coach.[23]

Society of American Indians

Chauncey Yellow Robe was one of the founders of the Society of American Indians (1911-1923), the first national American Indian rights organization developed and run by American Indians. The Society pioneered twentieth century Pan-Indianism, the philosophy and movement promoting unity among American Indians regardless of tribal affiliation. The Society was a forum for a new generation of American Indian leaders known as Red Progressives, prominent intellectuals and professionals from the fields of medicine, nursing, law, government, education, anthropology, ethnology and ministry, who shared the enthusiasm and faith of white reformers in the inevitability of progress through education and governmental action. The Society met at academic institutions, maintained a Washington headquarters, conducted annual conferences and published a quarterly journal of new American Indian literature by American Indian authors.

The Society was one of the first proponents of an "American Indian Day", and forefront in the fight for Indian citizenship and opening the U.S. Court of Claims to all tribes and bands in United States. The Society of American Indians was the forerunner of modern organizations such as the National Congress of American Indians, and anticipated by decades important Indian reforms: a major reorganization of the Indian school system in the late 1920s, the codification of Indian law in the 1930s, and the opening of the U.S. Court of Claims to Indians in the 1940s.[24]

Wild West shows

The Society of American Indians was opposed to Wild West shows, theatrical troupes, circuses and most motion picture firms. The Society believed that theatrical shows were demoralizing and degrading to Indians, and discouraged Indians from Wild Westing.[25] In October 1913, Chauncey spoke before the third Annual Conference of the Society of Americans Indians in Albany, New York,[26] He denounced Buffalo Bill Cody and General Nelson A. Miles’ controversial movie “The Indian War”, recreating battles of the Great Sioux War and the Wounded Knee incident “for their own profit and cheap glory.” [27] Chauncey argued, “What benefit has the Indian derived from Wild West shows? None but what are degrading, demoralizing and degenerating.”[28]

In October 1914, Chauncey addressed the Fourth Annual Convention of the Society, and condemned the “evil and degrading influence of commercializing the Indian” and the availability of alcohol.[29] Yellow Robe followed with an article, "The Menace of the Wild West Show", in the new Quarterly Journal of the Society of American Indians, writing that “Indians should be protected from the curse of the Wild West show schemes, wherein the Indians have been led to the white man’s poison cup and have become drunkards.” [30]

Marriage and children

In 1905, Yellow Robe married Lillian (Lillie) Belle Springer, of Swiss-German ancestry, from Tacoma, Washington. Lillie was a volunteer nurse at the Rapid City Indian School.[31] Chauncey and Lillian had three daughters, Rosebud, Chauncina[32] and Evelyn.[33] Chauncey chose to send his daughters to the Rapid City public schools instead of the Indian School because the public schools had academic orientation, while the Indian School focused on vocational courses in agriculture, blacksmithing and domestic arts. On occasion, elderly Indians would visit the grounds of the Indian School and tell stories in the Lakota language. Chauncey would have Rosebud listen, even though she could not understand a word, and later he would retell the stories in English. His children used and enjoyed the Indian School's library and programs.[34]

On April 6, 1927, Chauncey’s wife Lillie died at the age of forty-two, in Chauncey's words, "in the prime of her life and beautiful womanhood." [35] Soon thereafter, Rosebud assumed the for the care of her two younger sisters Chauncina and Evelyn, and they lived with her and her husband in New York City.[36]

War whoops in Rapid City

In the 1920s, Chauncey was invited to appear on an early radio show broadcast from the South Dakota School of Mines in Rapid City. Chauncey was nervous, but as the program progressed he became more confident and related his boyhood memories of the time of Custer’s defeat at the Little Big Horn and the stories he had heard from warriors returning from the battle. Reminiscing about the way he had lived with his people before they were confined to reservations, he was suddenly overcome with emotion and exploded in a war whoop that literally knocked out the radio transmitter. The station went off the air with the war whoop resounding as the final message of the day.[37]

U.S. President Calvin Coolidge

On August 4, 1927, U.S. President Calvin Coolidge and his wife visited the Black Hills of South Dakota. During the visit, Coolidge was adopted as an honorary member of the Sioux tribe in recognition of his support for the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924, granting full U.S. citizenship to all American Indians and permitting them to retain tribal land and cultural rights. The ceremony was presided over by Chief Chauncey Yellow Robe and Rosebud. Chauncey conferred upon President Coolidge the name "Leading Eagle" (Wamblee-Tokaha), while Rosebud placed a handmade Lakota warbonnet on the President's head.[38] At the time, Rosebud was a student at the University of South Dakota. Rosebud's image was widely reported by the press and she became an instant national celebrity. "Rosebud's grace and beauty were not lost on the press reporters, who commented on the 'beautiful Indian maiden'." [39] Thereafter, Rosebud was sought after by film and theatrical agents, and Chauncey was urged to run for the U.S. Congress.[40]

President Coolidge was impressed with Yellow Robe. "He represented a trained and intelligent contact between two different races. He was a born leader who realized that the destiny of the Indian is indissolubly bound up with the destiny of our country. His loyalty to his tribe and his people made him a most patriotic American" Coolidge noted, “No one could have witnessed the granting of this token of friendship and brotherhood without appreciating the spiritual significance, which Chief Yellow Robe gave to it. He wished to confer on me, as a representative of the Government of the United States, everything that he felt was good and worth preserving in the Indian life for the same reason that he constantly strove to teach his people to acquire and benefit by all he believed was good and worthy in the life of his people.” [41]

Politics

Chauncey Yellow Robe was known for his activities with the Society of American Indians. Yellow Robe spoke out many times critically, and in such a way he was considered a spokesman for the Sioux.[42] He believed that the majority of Anglos were ignorant of what Indians were capable of achieving, and urged Indians to fully participate in all aspects of American life. Chauncey, the Society of American Indians and others lobbied the federal government to grant Indians U.S. citizenship, and through their efforts citizenship was granted on June 2, 1924. “Many of his own people misunderstood Chauncey’s attitude. In their opinion he was working for the whites and deliberately undermining Lakota values. They failed to appreciate his point. He believed he was helping young students learn the fundamentals of living with the dominant culture." [43] Yellow Robe was keenly interested in politics, and the national publicity generated by President Coolidge’s visit to the Black Hills in 1928 made him an attractive candidate for office. When urged by Democratic supporters to oppose Congressman William Williamson in the next election, Chauncey replied, “If I am nominated for Congress, I will not look upon my candidacy as that of an Indian, but rather an American Citizen.” But Chauncey would die before the next election.[44]

“The Silent Enemy”

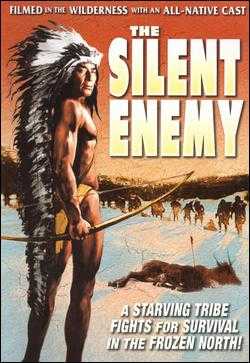

After his wife Lillie’s death, Chauncey took a leave of absence from the Rapid City Indian School, and with his youngest daughter, Evelyn, left for New York City to visit Rosebud. Chauncina arrived in New York from South Dakota shortly thereafter. Shortly after his arrival, Chauncey was approached by theatrical agents to play the role of an Indian chief in a film they were casting known as "The Silent Enemy". Chauncey had always denounced theatrical shows and movies that commercialized and demeaned Indians and initially refused the offer.[45] After visiting Rosebud for a few weeks, Chauncey returned to Rapid City, leaving Evelyn, now age seven, in Rosebud and Arthur’s care. Chauncina also remained in New York.

"The Silent Enemy" was an historically significant movie. Sponsored by the American Museum of Natural History, the production was the first movie with an all-Indian cast and no professional actors.[46] The production was an attempt to capture on film the authentic life style of pre-Columbian Indians, and portrayed the Ojibway in Canada as they faced the silent enemy of hunger. After conferring with the producers of the movie, Rosebud urged her father to reconsider because the movie would be an authentic depiction of Indian life, and would present an opportunity to show Anglos authentic Indian culture. In 1928, Chauncey finally agreed to appear in the leading role as Chief, and serve as technical director, and took leave from government service. Yellow Robe spent thirty weeks researching, writing, and acting for the film, and almost a year of hard and tedious work in including a frigid winter at Lake Temagami, Ontario.

On May 5, 1930, The Silent Enemy opened at the Criterion Theater on Broadway, and was acclaimed by the critics as one of the greatest Indian pictures ever produced. Unfortunately, during his stay in New York City to record the prologue, Chauncey contracted pneumonia and died at the Rockefeller Institute Hospital, on the third anniversary of his wife Lillie's death, April 6, 1930, a month before the opening date of the movie.

Chauncey Yellow Robe was buried according to Masonic rites beside his wife Lillian in Mountain View Cemetery in Rapid City, South Dakota.[47][48][49] Charles Badger Clark, poet laureate of South Dakota, said of him: “Having known two worlds, Yellow Robe is good for any third.” [50]

Other resources

- Kathleen Del Monte, Karen Bachman, Catherine Klein, Bridget McCourt, "Celebrating Women Anthropologists", http://www.cas.usf.edu/anthropology/women/rosebud/Rosebud.html.

- Marjorie Weinberg, "The Real Rosebud: The Triumph of a Lakota Woman", University of Nebraska Press (2004)

- Rosebud Yellow Robe, ”An Album of the American Indian”, 1969. ISBN 0803789734

- Rosebud Yellow Robe,“Tonweya and the Eagles, and other Lakota Indian Tales”, 1979. ISBN 0803789734

References

- ↑ Marjorie Weinberg, "The Real Rosebud: The Triumph of a Lakota Woman", (hereinafter "Weinberg), University of Nebraska Press (2004), p.13. See Chauncey Yellow Robe, "My Boyhood Days", The American Indian Magazine, Vol., 4, January–March, 1916, pp. 50-53. Chauncey's birth date is in dispute. His gravestone bears the year 1870. See http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=46168549.

- ↑ Weinberg, pp. 1-13. See http://anthropology.usf.edu/women/rosebud/Rosebud.html

- ↑ Donovin Arleigh Sprague, “Rosebud Sioux”, 2005, p. 79; Weinberg, p. 13.

- ↑ Weinberg, p.13.

- ↑ Weinberg, pp.13-14.

- ↑ Chauncey saw his first white man when his parents made cam near one of the trading posts along the Missouri River. He was playing near the camp when he saw a creature come toward them. It had long fair hair and a beard and was wearing a large hat and a fringed buckskin suit. He could not decide if it was a man or an animal, and as the creature approached, he decided it was an evil spirit and ran to the tipi of his father. Rosebud Yellow Robe, “Tonweya and the Eagles: And Other Lakota Tales, (hereinafter "Rosebud Yellow Robe"), p. 13.

- ↑ Rosebud Yellow Robe, p. 12.

- ↑ Weinberg, p. 12.

- ↑ Weinberg, p. 17. Donovin Arleigh Sprague, “Rosebud Sioux”, 2005, p. 79.

- ↑ Weinberg, p. 18.

- ↑ Weinberg, p. 19.

- ↑ Weinberg, p.19.

- ↑ “Chauncey Yellow Robe”, http://home.epix.net/~landis/chauncey.html

- ↑ L.G. Moses, “Wild West Shows and the Images of American Indians, 1883-1933, (hereinafter “Wild West Shows and Images”) (1996), p. 101. Indian Helper, November 21, 1890.

- ↑ Weinberg, p. 21.

- ↑ Weinberg, p.20.

- ↑ In 1920, on Pratt’s eightieth birthday, Chauncey wrote him: “I do not think there is any Carlisle man who is living today that is more indebted to you than I am. We have your photograph framed, hung on our wall and it is to me always a source of pleasure and comfort to look upon it. My life is your memorial.” Weinberg, p.29. See, Luther Standing Bear, “My People the Sioux," (1928), p.xx.

- ↑ My People the Sioux”, p. vi.

- ↑ Weinberg, p. 20.

- ↑ Weinberg, pp. 20-22.

- ↑ Weinberg, p.1, 22.

- ↑ In 1899, the Great Falls Tribune reported a performance by Yellow Robe and students from the Ft. Shaw Government School at the Grand Opera House. “We see by the Great Falls Tribune, Montana, that a fine performance was given recently at the Grand Opera House, by the pupils of the Ft. Shaw Government School for the benefit of the soldiers' monument fund. It is said that there had never before been a more thoroughly pleased audience in the Opera House, and that the work of the students reflected great credit upon the school and its management. Chauncey Yellow Robe, a graduate of our school, ('95) appears to have made a hit. His remarks were earnest and forcibly delivered, says the Tribune, and the whole audience frequently applauded his expressions. He made a plea for non-reservation schools for the Indians. He eloquently urged that the Indians are anxious for communication with the whites and for citizenship, and modestly cited himself as an instance of what the non-reservation schools may accomplish. ‘Five years ago I left Carlisle,’ he said, ‘and I am still on the warpath toward civilization.’ The audience heartily approved his suggestions, having abundant evidence of what one non-reservation school had done.” Indian Helper, July 6, 1899.

- ↑ Weinberg, p.24. The Rapid City Indian School was created in 1898 for Indian children from the Northern plains, including those from the Sioux, Northern Cheyenne, Shoshone, Arapaho, Crow, and Flathead tribes. It was one of the off-reservation Indian Boarding Schools established by the Bureau of Indian Affairs and was sometimes called "School of the Hills." It closed its doors as a school in 1933 and became a sanatorium for the treatment of tuberculosis for the Sioux. https://familysearch.org/learn/wiki/en/Rapid_City_Indian_School

- ↑ Hazel W. Hertzberg, "The Search for an American Indian Identity: Modern Pan-Indian Movements", Syracuse University Press, 1971, p. 117.

- ↑ See, E.H. Gohl, (Tyagohwens), “The Effect of Wild Westing”, The Quarterly Journal of the Society of American Indians, Washington, D.C., Volume 2, 1914, pp. 226-28.

- ↑ Moses, p. 133.

- ↑ Moses, pp. 239, 242. See Andrea I. Paul, 'Buffalo Bill and Wounded Knee: The Movie," Nebraska History 71 (1990), pp. 182-90 at http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/publicat/history/full-text/NH1990BuffBillMovie.pdf

- ↑ Moses, pp. 6, 224.

- ↑ Moses, p. 322. Dakota Images, South Dakota State Historical Society, Vol. 9, No. 2, (1979).

- ↑ Chauncey Yellow Robe, “The Menace of the Wild West Show”, The Quarterly Journal of the Society of American Indians, Washington, D.C., Volume 2,(July–September 1914), pp. 224-25.

- ↑ Lillie was born in Minnesota in 1885 and moved with her family to Tacoma, Washington, where she was reared and went to school. Her family had emigrated to the U.S. from the German-speaking city of Neftenbach, Switzerland, in 1854. Weinberg, p. 26.

- ↑ Chauncina Yellow Robe (January 28, 1909-June 13, 1981), also went into show business and traveled with rodeos and circuses, worked in selling advertising for the Yellow Pages. Later, she became a spokesperson for the Chicago Indian community and worked at the Chicago Indian Health Service. Chauncina inspired the establishment of the American Indian Oral History Project at the Newberry Library. Chauncina is buried at Saint Agnes Catholic Cemetery (Manderson), Shannon County, South Dakota. Weinberg, p. 53.

- ↑ Evelyn Y. Robe Finkbeiner, (December 25, 1919- ) graduated magna cum laude Mount Holyoke College, completing her Ph.D. at Northwestern University, in speech pathology. She served on the faculty Mount Holyoke and Vassar College. Evelyn was a Fulbright scholar and eventually settled in Germany with her husband, Dr. Hans Finkbeiner, an obstetrician and gynecologist. Weinberg, p. 53.

- ↑ Weinberg, p. 32.

- ↑ Weinberg, p.32.

- ↑ Weinberg, p. 34.

- ↑ Mildred Fielder, “War Whoop,” Rapid City Journal, May 11, 1969, cited Weinberg, pp. 31, 74.

- ↑ “It is the greatest honor to the Sioux Tribe of South Dakota to bestow upon you the emblem of the Sioux Nation in a war bonnet, and to welcome you to our tribe. We name you Leading Eagle, Wamblee-Tokaha. By this name you are to be known King and the greatest chief, which is signified by the bonnet and the name you bear. I congratulate you in the name of the Sioux Nation, and express the hope that you will continue to guide the will of this nation to its great destiny.” Weinberg, p.35.

- ↑ Sharon Malinowski and George H. J. Abrams, "Notable Native Americans", (1995), p.470.

- ↑ In 1928, Cecil B. DeMille, tried to persuade her to take the title role in his movie, Ramona, but she declined. Rosebud's friends said she was a dead ringer for silent screen star Dolores Del Rio, who eventually got the role of the heroine in the "Indian love lyric.""One of the telling passages is where Ramona discovers she is half Indian. Her joy is cleverly expressed, as she goes from one to another crying out that she is an Indian." Mordaunt Hall, "An Indian Love Lyric", New York Times, 15 May 1928, accessed 1 February 2011

- ↑ Weinberg, p.40-41. President Coolidge as quoted in Tonweya and the Eagles

- ↑ Rosebud Yellow Robe, p.17. Weinberg, p. 16.

- ↑ Weinberg, p. 25.

- ↑ Weinberg, p. 39. "Chauncey Yellow Robe, Dakota, Mentioned. An exchange says: One of the possibilities of the next campaign in South Dakota is that of a full blooded Sioux Indian, getting into the race for congress from the third congressional district, according to a recent dispatch from Pierre, S.D., as published in various newspapers in the East. “Carlisle Indian Running for Congress”, The Evening Sentinel, Monday, December 12, 1927.

- ↑ Weinberg, p.38.

- ↑ Rosebud Yellow Robe, p. 17.

- ↑ Weinberg, p. 40. “Chief Yellow Robe, Sioux Educator, Dies: Devoted Most of his 63 years to his People”, New York Times, April 8, 1930.

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ Rosebud Yellow Robe, p. 116.