Charles Angrand

| Charles Angrand | |

|---|---|

Self-Portrait, 1892 Conté crayon on laid paper, 62.2 x 46 cm | |

| Born |

Charles Théophile Angrand 19 April 1854 Criquetot-sur-Ouville, Normandy, France |

| Died |

1 April 1926 (aged 71) Rouen, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Education | Académie de Peinture et de Dessin, Rouen |

| Known for | Painting, drawing |

| Movement | Impressionism, Neo-Impressionism (Pointillism) |

Charles Angrand (19 April 1854 – 1 April 1926) was a French artist who gained renown for his Neo-Impressionist paintings and drawings. He was an important member of the Parisian avant-garde art scene in the late 1880s and early 1890s.

Early life and work

Charles Théophile Angrand was born in Criquetot-sur-Ouville, Normandy, France, to schoolmaster Charles P. Angrand (1829–96) and his wife Marie (1833–1905).[1]

He received artistic training in Rouen at Académie de Peinture et de Dessin.[2] His first visit to Paris was in 1875, to see a retrospective of the work of Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot at École des Beaux-Arts.[1] Corot was an influence on Angrand's early work.[3]

After being denied entry into École des Beaux-Arts, he moved to Paris in 1882, where he began teaching mathematics at Collège Chaptal.[4] His living quarters were near Café d'Athènes, Café Guerbois, Le Chat Noir, and other establishments frequented by artists. Angrand joined the artistic world of the Parisian avant-garde,[5] becoming friends with such luminaries as Georges Seurat, Vincent van Gogh,[5] Paul Signac, Maximilien Luce, and Henri-Edmond Cross.[3] His avant-garde artistic and literary contacts influenced him, and in 1884 he co-founded Société des Artistes Indépendants, along with Seurat, Signac, Odilon Redon, and others.

Art

Musée d'Orsay, canvas, 38.5 x 33.0 cm

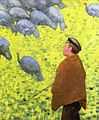

Angrand's Impressionist paintings of the early 1880s, generally depicting rural subjects and containing broken brushstrokes and light-filled colouration, reflect the influences of Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro,[4] and Jules Bastien-Lepage.[2] Through his interactions with Seurat, Signac, and others in the mid-1880s, his style evolved towards Neo-Impressionism.[4] From 1887 his paintings were Neo-Impressionist and his drawings incorporated Seurat's tenebrist style. Angrand had the "ability to distil poetry from the most banal suburban scene".[2] In 1887 he met van Gogh,[4] who proposed a painting exchange (which ultimately did not happen).[6] Van Gogh was influenced by Angrand's thick brushstrokes and Japanese-inspired compositional asymmetry.[7] Also in 1887, L'Accident, his first Divisionist painting, was exhibited at the Salon des Indépendants. Angrand joined Seurat in plein air painting on La Grande Jatte island.[5]

Angrand's implementation of Pointillist techniques differed from that of some of its leading proponents. He painted with a more muted palette than Seurat and Signac, who used bright contrasting colours. As seen in Couple in the street, Angrand used dots of various colours to enhance shadows and provide the proper tone, while avoiding the violent colouration found in many other Neo-Impressionist works. His monochrome conté crayon drawings such as his self-portrait above, which also demonstrate his delicate handling of light and shadow,[8] were assessed by Signac: "... his drawings are masterpieces. It would be impossible to imagine a better use of white and black ... These are the most beautiful drawings, poems of light, of fine composition and execution."[9]

Angrand exhibited his work in Paris at Les Indépendants, Galerie Druet, Galérie Durand-Ruel, and Bernheim-Jeune, and also in Rouen. His work appeared in Brussels in an 1891 show with Les XX.[4] In the early 1890s, he abandoned painting, instead creating conté drawings and pastels[4] of subjects including rural scenes and depictions of mother and child, realized in dark Symbolist intensity. During this period, he also drew illustrations for anarchist publications such as Les Temps nouveaux;[2] other Neo-Impressionists contributing to these publications included Signac, Luce, and Théo van Rysselberghe.[10]

Later years

In 1896 he moved to Saint-Laurent-en-Caux, in Upper Normandy.[4] He began painting again around 1906, emulating the styles and colours of Signac and Cross.[11] Angrand developed his own unique methods of Divisionism, with larger brushstrokes. As this resulted in rougher optical blending than small dots, he compensated by using more intense colours.[12] Some of his landscapes from this period are almost nonrepresentational.[11] Before World War I, he lived for a year in Dieppe. Then he moved back to Rouen, living there for the rest of his life. He was very reclusive for his last thirty years, but remained a dedicated correspondent.[4] Angrand died in Rouen on 1 April 1926. He is buried in Cimetière monumental de Rouen.[13]

Collections

Angrand's work is in many museum collections, including Ateneum (Finnish National Gallery),[14] Cleveland Museum of Art,[15] Hecht Museum,[12] Indianapolis Museum of Art,[16] Metropolitan Museum of Art,[9] Musée d'Orsay,[17] Museum of Fine Arts, Boston,[18] and Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek.[6][19]

Influence

In 2010, LAVA [20] created the Charles Angrand (Artwork) Award, which has been awarded annually since 2011. The LAVA Awards are held annually to honor excellence in books relating to the principles of liberty, with the Charles Angrand Award being the grand prize award for artwork.

Gallery

-

Le Pont De Pierre,

ca. 1880 -

The Guardian of Turkeys, 1881

-

Feeding the Chickens, 1884

-

Path in the Country,

ca. 1886 -

The Harvest, 1890

-

The Little Farm, 1890

-

The Harvesters, 1892

-

Farmyard, 1892

-

Le Petit Port

-

Hay Ricks in Normandy

-

Mother and Child

-

Wheat

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Clement, p. 311.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Turner, p. 3.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Charles Angrand Biography". Olga's Gallery. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 Clement, p. 309.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Clement, p. 312.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "To Charles Angrand. Paris, Monday, 25 October 1886.". Vincent van Gogh Letters. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ↑ "Charles Angrand: The Western Railway at its Exit from Paris". National Gallery, London. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ↑ Owens, Emilie (2009). "Masterpieces from Paris: Charles Angrand – Couple dans la rue". National Gallery of Australia. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Charles Angrand: Self-Portrait". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Metropolitan Museum of Art. October 2006. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ↑ "Jean Grave". The Anarchist Encyclopedia. Recollection Books. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Turner, p. 4.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "Angrand Charles". Hecht Museum. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ↑ "Le cimetière monumental à Rouen". Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ↑ "Art Collections - Angrand, Charles". Finnish National Gallery. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ↑ "End of the Harvest: Charles Angrand". Cleveland Museum of Art. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ↑ "Angrand, Charles". Indianapolis Museum of Art. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ↑ "Charles Angrand: Antoine Sleeping". Musée d'Orsay. 2006. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ↑ "Farmyard". Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ↑ "Angrand, Charles". Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ↑ The Libertarian, Agorist, Voluntaryist and Anarch Authors and Publishers Association

Sources

- Clement, Russell T.; Houzé, Annick (1999). Neo-Impressionist Painters: a Sourcebook on Georges Seurat, Camille Pissarro, Paul Signac, Théo Van Rysselberghe, Henri Edmond Cross, Charles Angrand, Maximilien Luce, and Albert Dubois-Pillet. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-30382-7. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- Turner, Jane; Thomson, Richard (2000). The Grove Dictionary of Art: From Monet to Cézanne: Late 19th-Century French Artists. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-22971-2. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

Further reading

- Spiess, Dominique (1992). Encyclopedia of Impressionists: From the Precursors To the Heirs. Lausanne: Edita. ISBN 2-88001-289-9.

External links

- Signac, 1863-1935, a fully digitized exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries, which contains material on Charles Angrand (see index)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charles Angrand. |

|