Chaonei No. 81

| Chaonei No. 81 | |

|---|---|

| 朝内81号 | |

|

West (front) elevation of main house in 2014 | |

| Alternative names | Chaonei Church, No. 81 |

| Etymology | Street address |

| General information | |

| Status | Vacant |

| Type | House |

| Architectural style | French Baroque revival |

| Location | Chaoyangmen neighborhood, Dongcheng District |

| Address |

81 Chaoyangmen Inner Street (朝阳内大街81号) |

| Town or city | Beijing |

| Country | China |

| Coordinates | 39°55′25″N 116°25′24″E / 39.92355°N 116.42329°ECoordinates: 39°55′25″N 116°25′24″E / 39.92355°N 116.42329°E |

| Completed | 1910 |

| Owner | Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Beijing |

| Technical details | |

| Material | Brick, stone |

| Floor count | 3 |

Chaonei No. 81 (simplified Chinese: 朝内81号; traditional Chinese: 朝內81號; pinyin: Cháo nèi bāshí lī hào, short for simplified Chinese: 朝阳门内大街81号; traditional Chinese: 朝陽門內大街81號; pinyin: Chāoyáng mén nèi dàjiē bāshí lī hào or Chaoyangmen Inner Street No. 81), sometimes referred to as Chaonei Church,[1] is a house located in the Chaoyangmen neighborhood of the Dongcheng District in Beijing, China. It is a brick structure in the French Baroque architectural style built in the early 20th century, with a larger outbuilding. The municipality of Beijing has designated it a historic building.[2]

It is best known for the widespread belief that it is haunted, and it has been described as "Beijing's most celebrated 'haunted house'". Stories associated with the house include ghosts, usually of a suicidal woman, and mysterious disappearances. It has become a popular site for urban exploration by Chinese youth, especially after a popular 2014 3D horror film, The House That Never Dies, was set there.[3]

Due to incomplete historical records, there is disagreement about who built the house and for what purpose; however it is accepted that, contrary to one frequently cited legend, the house was never the property of a Kuomintang officer who left a woman, either his wife or a mistress, behind there when he fled to Taiwan in 1949. Since the establishment of the People's Republic of China (PRC) that year, records are more consistent. It was used as offices for various government agencies for most of the PRC's early years. During the Cultural Revolution, in the late 1960s, it was briefly occupied by the Red Guards; their hasty departure from the property has been cited as further evidence of the haunting. It is currently owned by the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Beijing, which in the late 1990s raised the possibility that it might one day serve as the Vatican embassy as a reason for not demolishing it.[2]

Buildings and grounds

The house is located along the north side of the street, about 250 metres (820 ft) west of the Second Ring Road intersection, the former site of the Chaoyangmen gate for which the neighborhood is named. It is in the Chaoyangmen Subdistrict of Beijing's Dongcheng District, near the boundary with the neighboring Chaoyang District. The property is midway between the intersections with Douban and Nanshuiguan hutongs to its east and Chaoyangmen Alley to its west.[4]

Chaoyangmen Inner is a four-lane road at that point, divided in the center by a concrete median with a metal fence. Separate local lanes exist on either side. Scattered around the intersection with the Ring Road are exits and entrances to the Chaoyangmen station on Lines 2 and 6 of the Beijing Subway. A pedestrian overpass crosses the street a short distance east of the property; another two cross the Chaoyangmen Alley intersection to the west.[5]

The neighborhood is urban and densely developed. At the intersection with the ring road is the distinctively shaped headquarters of the China National Offshore Oil Corporation; other high-rises are on the neighboring corners. Further west are lower-height mixed-use buildings with stores at street level and apartments above. Short driveways and narrow alleys lead to two-story residential buildings in the interior of the block, separated by occasional rows of trees.[5]

A concrete wall surrounds the property, with a gate of opaque metal doors allowing entrance from the street. Mature deciduous trees along the inside screen the property. There are three buildings on the 750-square-metre (8,100 sq ft) parcel—the main house, a larger second house, and a garage. The land surrounding them is not planted or landscaped and is usually bare dirt or gravel. Cars are frequently parked here. Some small scrubby deciduous trees grow at various points on the lot.[5]

Main house

The main house is located east of the entrance. It is a two-and-a-half-story structure of brick laid in Flemish bond with stone trim topped by a shingled mansard roof that further rises to a tiled hipped peak in the middle, pierced by a brick chimney. Part of an exposed stone basement can be seen below the first floor. It consists of a three-by-three-bay main block with a three-by-two-bay north wing.[6]

On the west (front) elevation the southernmost bay projects on all levels, creating a small pavilion. Stone water tables set off the basement and the second story. a third along the top of the windows on the latter marks the middle of the plain stone frieze below the damaged modillioned cornice from which some trees sprout. On the first story a second course caps a stone face; it is higher on the north side of the main entrance than the south. All corners are quoined in stone. Metal drainpipes fed by older pipes run down the facade on both sides of the pavilion and just south of the north corner.[6]

Stone steps lead up to the centrally located main entrance. It is sheltered by a stone balcony supported by two smooth rectangular columns in front with inverse-stepped capitals supporting a similar cornice, whose stonework also has been damaged. A wider section in the rear of the balcony is supported by slightly larger pilasters with similar treatment. Both columns and pilasters are in turn resting on tall plinth blocks. Atop the balcony is a stone balustrade.[6]

Fenestration is regular in placement, with one window per bay on each story, and treatment, with all windows in quoined stone surrounds and splayed stones with a keystone atop the lintel. Otherwise it is irregular, with each opening set differently. The southern pavilion has a wooden French door topped with a two-light transom. A small step protrudes at floor level. The side quoining continues up to the mid-facade water table, enclosing a slightly raised stone panel with a carved foliate design.[6]

A similar stone panel, with a different foliate design but likewise flanked by the window quoining, is located below the window on the north side of the entrance. Within is a deeply recessed double six-pane casement window topped by a four-pane transom. Most panes are gone.[6]

On the second story, behind the balcony, the opening is empty. It seems to have been meant to hold another French door and transom combination. The south window has a six-pane double casement like the northern window on the story below, but with elongated middle pane. It, too, is topped with a four-pane transom similar to the one below it. Most of its panes remain. The northern window is elliptical, with its window another six-pane casement with longer middle pane cut to fit. All of its panes are gone.[6]

Above the roofline, three dormer windows pierce the mansard. They are brick with stone trim at the corners, plain rectangular forms that echo the more ornate front entrance balcony below. Atop each is a gently curved round arched pediment of stone, revealing brick in their minimal entablatures. Set within the dormer is a deeply recessed double three-pane casement window. Most of the panes are missing, and only the wooden support frame remains in the southern window.[6]

The south facade faces the street. On it, the courses and water tables continue as they do on the west; however the facade is entirely brick except for the basement. The north bay of the first story has a French door similar to the one around the corner, but more ornate. It is flanked by two casement windows with elongate middle panes topped by a two-pan transom of almost the same height as the door. Atop it the quoins continue, enclosing yet another foliated stone panel. There are two holes punched in the facade near the east corner, one at the top of each story.[6]

East of the blind middle bay is a one-story bay window with stone facing covering most of the brick. Its central facet has another, more deeply recessed French door with alternating long and short panes topped by a similar transom; the flanking facets have similar windows, shorter and narrower. Beneath them the brick is exposed. Another balustraded balcony rises above a damaged cornice; a French door, no longer present, provides access. In the middle bay is an elliptical window identical to the one in the second story of the west facade; the west bay has an intact casement with elongated middle and transom. Two dormers pierce the mansard on the attic level.[6]

On the east (rear) facade, the south bay projects to form a pavilion as well. The water tables, course and roof cornice continue here. On its first level it has a tripartite French door (mostly gone with only shards of glass remaining) with the same treatment as the one on the west corner of the south side, save for the stone panel being plain. Above it is a deeply recessed casement window with elongated middle pane and a dormer identical to the others. A single drainpipe, similar to the ones on the opposite side, runs down the pavilion facade on the south side.[6]

The other windows, on both stories, are all set with the same transomed casement. They are topped with stone panels, all with the same foliate design. Above, the dormers continue to the northern corner, set instead with a small stone chimney. A modern brick wing, occupied, protrudes from the first floor near the north end. Its roof receives one of the two drainpipes on this face.[6]

Outbuildings

A larger six-by-five-bay outbuilding, three stories high with a single-bay tower on the southeast corner, is located to the northwest. It is similar in style to the main house but in worse condition. The exposed brick facade is covered with discoloring brownish dust that makes it appear the same color as the stone, and most of the windows are completely gone, leaving only openings. With the main house it shares the water tables, course and modillioned cornice at the same positions on its facades, and the quoined window surrounds.[6]

The entrance is on the easternmost bay of the house, wide enough for a double door. Above it is a window opening displaced upward so that its lintel is the water table between the two lower stories. All the bays to the west are similar in size to the casement window bays on the main house, with the fifth having two openings. The second story is similar, with the eastern bay holding a smaller eyebrow window displaced upward, like the one below. The east profile has a single side entrance in its middle bay topped by a window on the second story. Four dormers, with the same treatment as those on the main house, pierce the mansard.[6]

The eastern tower is heavily overgrown with vines. It consists of three stages. On the lower, brick pilasters with plain stone capitals connected by a plain frieze frame a single casement window frame with its four transom panes remaining. The east side is blind.[6]

Above it the middle stage is an engaged stone balustrade similar to those on the main house. It is topped with the final stage, plain stone-faced shallow-pitched gable-roofed portion with overhanging eaves. A single window opens on the south side.[6]

In the southwest corner of the lot is the last building, a small one-story brick gable-roofed structure. It, too, is in a state of disrepair, with half the roof tiles missing and the brickwork crumbling in some areas; however it is in use. A wooden paneled door opens into the structure on the north side of its three-bay east (front) elevation; to its south are two windows, both set with double three-pane casement windows over two lower fixed panes.[6]

History

"The history is very difficult to get straight," Xu Wen, one of the property's groundskeepers, told The New York Times in 2014, as building records predating the 1949 establishment of the People's Republic of China are inconsistent or missing. Most commonly, it is believed to have been built around 1910 as the North China Union Language School, to teach Mandarin Chinese to missionaries from the West. Two decades later, it broadened its educational mandate and welcomed businessmen, diplomats and scholars to its classes, as the California College in China, part of the system that became today's Claremont Colleges. Among those who studied there was John K. Fairbank, later a Harvard professor and China Hand at the middle of the century.[2]

This is the account given by the current owner, the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Beijing. It is not universally accepted. Other historians of Beijing believe that the California College building was in a different building, and that the building was actually a house for the manager of the Beijing–Hankou Railway at that time, who happened to be French.[2] Still other accounts suggest the building was older, dating to at least 1900, and built by the Imperial Chinese government at that time as a gift to either the British government or the Catholic Church, for some religious purpose, either to house missionaries or use as a church.[1][7][8]

By the late 1930s it had become the property of a Catholic organization, possibly an American Benedictine group. An Irish-born priest may have attempted to use it in 1937, after which, the diocese claims, it was used by a group of Belgian Augustinian nuns as a clinic during World War II and until at least 1946.[9] At the time of the Communist victory in the Chinese Civil War three years later, it was being run by the Irish Presbyterian Mission. Shi Hongxi, secretary general of the Beijing chapter of the Chinese Patriotic Catholic Association (CPCA), which oversees the property's current owner, the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Beijing, says there is no record of a Kuomintang officer living there, the basis for the most common story of the house's alleged haunting, at that time in history.[2]

After 1949, ownership and use records are available. The new Communist government took control, and used the buildings intermittently throughout the 1950s and early 1960s to house various government departments and agencies. By the time of the Cultural Revolution it had remained unused for some time, and according to a local resident it was briefly occupied by a group of Red Guards who left because they were frightened.[2] Since then it does not appear to have been used by anyone either as a residence or workplace, and fell into disrepair.[2]

In 1980, the State Administration for Religious Affairs and United Front Work Department, in conjunction with other government agencies, issued an order requiring that anyone using a property that had been used for religious purposes prior to 1949 leave it and returning all those properties to the religious organizations that had previously owned them. In the case of Chaonei No. 81, this was difficult due to the incomplete records of ownership from that time. Neglected, the house continued to deteriorate.[10]

The property was finally transferred to the CPCA in 1994 when it was able to prove the Catholic Church's past use to the government's satisfaction. By that time Beijing's real estate market was booming as reforms by Deng Xiaoping liberalized the Chinese economy, and the buildings had reached the point where they were close to being demolished. The archdiocese suggested that the complex would be ideal for use as the Vatican embassy should relations between it and China improve to the point that ambassadors were exchanged.[2]

However, the diocese did not have the resources to do the needed renovations. Between 2003 and 2005 it listed the project as one of its top priorities, but then Fu Tieshan, the CPCA secretary who had been instrumental in saving the property, died and it was put on hold. In 2009 the municipal government listed the property as historic, since it had changed very little in a century.[11]

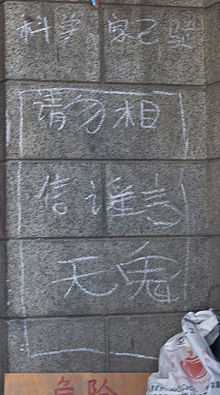

While the heritage listing prevented the buildings from being torn down, it also made it difficult to renovate since strict historic preservation rules have to be followed. In 2010 the diocese started the approval process again.[12] During the preceding years legends about the old deteriorated, overgrown house in the middle of an otherwise modern, developing neighborhood being haunted spread, and local teenagers flocked to it out of curiosity. Despite the diocese's ban on entering the house due to its structural deficiencies, and graffiti warning of the haunting, many entered the house anyway, for urban exploration or just to have parties, the latter group leaving empty beer bottles and cigarette butts behind, further contributing to the house's decrepitude.[2]

In 2011, Hong Kong filmmakers Raymond Yip and Manfred Wong began what would ultimately be three years of preproduction for The House That Never Dies, a horror film set at Chaonei No. 81. While they ultimately used another house in Beijing and locations in Wuxi instead of the real property, they and their cast visited the house, and Yip reviewed 3,000 pages of data on the house in preparation for directing the film.[13] Prior to its 2014 release, at the request of the diocese, they changed the film's Chinese title from the name of the house to 京城81号 (Chinese: 京城81號; pinyin: Jing Cheng 81 Hao, or Capital City No. 81) and left the number out for its English title.[14]

Wong and Yip decided to shoot the movie in 3D, the first time the 21st-century version of that technique had been used for a Chinese production. Upon release in late July, the film was a huge success, grossing CN¥154 million (US$24.9 million) on its opening weekend, not only the best ever for a horror film in China but enough to make it the highest-grossing Chinese horror film ever.[15] Youths who saw the film flocked to see the actual house, in some cases mere blocks from theaters showing it. As many as 500 showed up to visit on a single day; some engaging in cosplay with the house as a backdrop. The diocese decided to close the gates and allow only a few into the house at a time due to its structural issues.[3]

Haunting and other reported paranormal phenomena

"Even in the 1970s, people thought the house was haunted... As children, we would play hide-and-seek in the house, but we didn't dare come in by ourselves," Li Jongyie, who grew up in one of the nearby hutong, the traditional alleyways of central Beijing, recalled to The New York Times in 2013. The Red Guards who moved into the house during the previous decade's Cultural Revolution supposedly left after a few days because they were frightened, he said.[2]

The ghost most commonly claimed to be haunting the house is that of a woman. She has been described as either the wife or lover of an officer in the National Revolutionary Army, the military arm of the Kuomintang (KMT), during the Chinese Civil War in the late 1940s. When he fled to Taiwan with his compatriots in advance of the Communist victory at the end of the war, she was left behind. Despondent, she hung herself from the rafters. Some other accounts suggest the war's outcome had nothing to do with her suicide; she was simply lonely as he was rarely home due to the war.[16] While the archdiocese says that story is completely false, as no record has ever been found suggesting that a KMT officer lived there or owned the house,[2] local lore has it that she can be heard screaming from the empty house during thunderstorms.[1] However, it has also been suggested that the screaming comes from people who sneak in at night expressly to do so.[17]

There have also been allegations of inexplicable disappearances connected to the house. The first claims that a British priest who had built the property, supposedly to be used as a church, went missing before it was finished. Investigators sent to look for him supposedly discovered instead a secret tunnel in the crypt that led to the Dashanzi neighborhood to the northeast.[16] In the second, three construction workers in the basement of a neighboring building got drunk on the job, and decided to break through the thin wall between where they were and No. 81. After going through it they have reportedly never been seen again.[1] It is claimed that this incident, rather than the diocese's interest in the building, is what led the government to cancel its plans to demolish the buildings in the late 1990s.[7]

Other paranormal phenomena have been associated with the house. One claim is that anyone who walks by experiences a feeling of unease or dread while they do so.[16] It is also said that during summers, it is always cooler in the mansion's doorway than another shaded entryway of a modern house just 20 metres (66 ft) away.[1]

The rumors and legends may have practical effects, making the property impossible to sell or lease despite the otherwise liquid real-estate market in the area. Although the diocese estimates that repairs to the house would cost at least US$1.5 million, that would be unlikely to deter buyers since similar properties nearby have been sold for several times that amount.[18] The Chinese avoid things associated with death, sometimes avoiding the use of the number 4 just because the Chinese word for it is pronounced almost identically to the Chinese word for "death".[2] A chalked notice next to the main entrance states, however, that there are no ghosts inside.

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Ge, Wang (June 15, 2011). "Chaonei Church: A church and supposedly haunted house". Time Out Beijing. Retrieved October 13, 2014.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 2.10 2.11 Qin, Amy (September 25, 2013). "Dilapidated Mansion Has Had Many Occupants, Maybe Even a Ghost". The New York Times. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Qin, Amy (July 22, 2014). "Film Has Crowds Swarming to Beijing House, Haunted or Not". The New York Times. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

- ↑ ACME Mapper (Map). Cartography by Google Maps. ACME Laboratories. Retrieved October 14, 2014.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 ACME Mapper (Map). Cartography by Google Maps. ACME Laboratories. Retrieved October 14, 2014.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 6.9 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 6.14 6.15 See accompanying photos

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Horn, Leslie (September 26, 2013). "This Amazing Chinese Mansion Is Abandoned Because It's Haunted". Gizmodo.com.au. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- ↑ Liu, Ke (August 8, 2014). 北京朝内81号是“鬼宅”为虚构. Sina.com (in Chinese). Retrieved October 17, 2014.

坊间流传的皇帝赐给英国人教堂、外国夫妻合开医院、军阀宅院等不同版本均不属实。

- ↑ Liu, "1933年美国天主教本笃会总部内部调整,将在北京的所有产业交给了天主教其他机构管理。1937年,爱尔兰天主教味增爵会孔文德神父将朝内81号改作教堂使用。1946年,比利时天主教奥斯定修女会曾在此设立普德诊所直至北平解放。新中国成立后,此处宗教教产被北京市民政局使用,后成为北京市民政工业公司办公地。"

- ↑ Liu, "1980年,由中央统战部、国家宗教局等部委联合发布188号文件,要求各单位无条件腾退新中国成立后占用的宗教房产。“朝内81号就属于被占的宗教房产。”石洪喜说,由于缺乏历史资料佐证,收回工作进展缓慢。"

- ↑ Liu, "'100多年了,外观和内部结构几乎没有变化。'石洪喜说 ... 据石洪喜介绍,修缮朝内81号院被列入教会的重要日程,从2003年至2005年,所有手续基本办齐,但由于傅铁山逝世等原因,修缮工作又被搁置 ... 2009年,朝内81号被列为北京市东城区文物保护单位。计划征集史料 年底有望开工修缮"

- ↑ Liu, "其实早在2010年,北京市天主教会就准备重启朝内81号的修缮工作,但由于被列为文保单位,依据相关法律法规,修缮必须重新审批。"

- ↑ 《朝內81號》曝海報 林心如上演冥婚. Sina Beijing (in Chinese). February 25, 2014. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

據了解,該片以近億元的投資,長達三年的籌備期,一年的製作期,成為二人合作以來的“最大手筆”。

- ↑ Liu, "教会立即向有关部门提出异议,虽然后来电影更名为《京城81号》,但电影里的建筑外观一看就能让人联想到朝内81号。"

- ↑ Ma, Jack (July 22, 2014). "Tiny Times 3 dazzles at China box office". Film Business Asia. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 "Top 8 Haunted Places in Beijing". China Daily. July 26, 2013. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- ↑ "'Haunted house' in Beijing: Chaonei No. 81". China Daily. August 4, 2012. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- ↑ Hickman, Matt (October 28, 2013). "In Beijing, a ghost-plagued fixer-upper that eludes renovation". Mother Nature Network. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

External links

Media related to Chaonei No. 81 at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Chaonei No. 81 at Wikimedia Commons