Cetacea

| Cetaceans[1] Temporal range: 55–0Ma Early Eocene – Present | |

|---|---|

| |

| Humpback whale breaching | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Clade: | Cetancodontamorpha |

| Suborder: | Whippomorpha |

| Infraorder: | Cetacea Brisson, 1762 |

| Parvorders | |

|

Mysticeti | |

| Diversity | |

| Around 88 species. | |

The infraorder[2] Cetacea /sɨˈteɪʃⁱə/ includes the marine mammals commonly known as whales, dolphins, and porpoises. Cetus is Latin and is used in biological names to mean 'whale'. Its original meaning, 'large sea animal', was more general. It comes from Ancient Greek κῆτος (kētos), used for whales and other huge fish or sea monsters. Cetology is the branch of marine science associated with the study of cetaceans. An ancient ancestor of the whale, Basilosaurus was thought to be a reptile until vestigial parts were recognized.[3] Traditionally Cetacea was treated as an order, but it has become increasingly aware based on physiological data that cetaceans are not only a clade of even-toed ungulates, but that Cetacea might be recognized as an infraorder.[2]

Fossil evidence suggests that the cetaceans share a common ancestor with hippopotamuses that began living in marine environments around 50 million years ago.[4][5][6][7] Today, they are the mammals best adapted to aquatic life. The body of a cetacean is fusiform (spindle-shaped). The forelimbs are modified into flippers. The tiny hindlimbs are vestigial; they do not attach to the backbone and are hidden within the body. The tail has horizontal flukes. Cetaceans are nearly hairless, and are insulated from the cooler water they inhabit by a thick layer of blubber.

Some species are attributed with high levels of intelligence. At the 2012 meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, support was reiterated for a cetacean bill of rights, listing cetaceans as non-human persons.[8]

The collective noun "pod"[9] is often used for a herd or school of marine mammals, especially a small herd or family group of whales or dolphins.

Physical characteristics

Respiration

Cetaceans breathe air, and surface periodically to exhale carbon dioxide and inhale a fresh supply of oxygen. During diving, a muscular action closes the blowholes (nostrils), which remain closed until the cetacean returns to the surface; when it surfaces, the muscles open the blowholes and warm air is exhaled.

Cetaceans' blowholes have evolved to a position at the top of the head, simplifying breathing in sometimes rough seas. When the stale air, warmed from the lungs, is exhaled, it condenses as it meets colder external air. As with a terrestrial mammal breathing out on a cold day, a small cloud of 'steam' appears. This is called the 'blow' or 'spout' and varies by species in terms of shape, angle, and height. Species can be identified at a distance using this characteristic.

Cetaceans can remain under water for much longer periods than most other mammals, (about seven to 120 minutes, varying by species) due to large physiological differences. Two studied advantages of cetacean physiology let this order (and other marine mammals) forage underwater for extended periods without breathing:

- Mammalian myoglobin concentrations in skeletal muscle have much variation. New Zealand white rabbits have 0.08 to 0.60% myoglobin by weight in wet muscle,[10] whereas a northern bottlenose whale has 6.34 grams (0.224 oz) myoglobin per 100 grams wet muscle.[11] Myoglobin, by nature, has a higher oxygen affinity than hemoglobin. The higher the myoglobin concentration in skeletal muscle, the longer the animal can stay underwater.

- Increased body size also increases maximum dive duration. Greater body size implies increased muscle mass and increased oxygen stores. Cetaceans also obey Kleiber's law, which states that mass and metabolic rate are inversely related, i.e., larger animals consume less oxygen than smaller animals per unit mass.

Vision, hearing and echolocation

Cetacean eyes are set on the sides rather than the front of the head. This means only cetaceans with pointed 'beaks' (such as dolphins) have good binocular vision forward and downward. Tear glands secrete greasy tears, which protect the eyes from the salt in the water. The lens is almost spherical, which is most efficient at focusing the minimal light that reaches deep water. Cetaceans make up for their generally poor vision (with the exception of the dolphin) with excellent hearing.

The external ear of cetaceans has lost the pinna (visible ear), but still retains an extremely narrow external auditory meatus. To register sounds, instead, the posterior part of the mandible has a thin lateral wall (the pan bone) behind which a concavity houses a large fat pad. The fat pad passes anteriorly into the greatly enlarged mandibular foramen to reach in under the teeth, and posteriorly to reach the thin lateral wall of the ectotympanic. The ectotympanic only offers a reduced attachment area for the tympanic membrane and the connection between this auditory complex and the rest of the skull is reduced in cetaceans — to a single, small cartilage in oceanic dolphins. In odontocetes, the complex is surrounded by spongy tissue filled with air spaces, while in mysticetes it is integrated into the skull similar to land mammals. In odontocetes, the tympanic membrane (or ligament) has the shape of a folded-in umbrella that stretches from the ectotympanic ring and narrows off to the malleus (quite unlike the flat, circular membrane found in land mammals.) In mysticetes, it also forms a large protrusion (known as the "glove finger"), which stretches into the external meatus, and the stapes are larger than in odontocetes. In some small sperm whales, the malleus is fused with the ectotympanic. The ear ossicles are pachyosteosclerotic (dense and compact) in cetaceans and very different in shape compared to land mammals (other aquatic mammals, such as sirenians and earless seals, have also lost their pinnae). In modern cetaceans, the semicircular canals are much smaller relative to body size than in other mammals.[12]

In modern cetaceans, the auditory bulla is separated from the skull and composed of two compact and dense bones (the periotic and tympanic) referred to as the tympano-periotic complex. This complex is located in a cavity in the middle ear, which, in Mysticeti, is divided by a bony projection and compressed between the exoccipital and squamosal but, in Odontoceti, is large and completely surrounds the bulla (hence called "peribullar"), which is therefore not connected to the skull except in physeterids. In odontoceti, the cavity is filled with a dense foam in which the bulla hangs suspended in five or more sets of ligaments. The pterygoid and peribullar sinuses that form the cavity tend to be more developed in shallow water and riverine species than in pelagic mysticeti. In odontoceti, the composite auditory structure is thought to serve as an acoustic isolator, analogous to the lamellar construction found in the temporal bone in bats.[13]

Odontoceti (toothed whales, which includes dolphins and porpoises) are generally capable of echolocation.[14] From this, Odontoceti can discern the size, shape, surface characteristics, distance and movement of an object. With this ability, cetaceans can search for, chase and catch fast-swimming prey in total darkness.[15] Echolocation is so advanced in most Odontoceti, they can distinguish between prey and nonprey (such as humans or boats); captive Odontoceti can be trained to distinguish between, for example, balls of different sizes or shapes. Mysticeti (baleen whales) have exceptionally thin, wide basilar membranes in their cochleae without stiffening agents, making their ears adapted for processing low to infrasonic frequencies.[16]

Cetaceans also use sound to communicate, whether it be groans, moans, whistles, clicks, or the complex 'singing' of the humpback whale. Besides hearing and vision, at least one species, the tucuxi or Guiana dolphin, is able to use electroreception to sense prey.[17]

Tails

All cetaceans have tails containing (or known as) flukes. These lobes are horizontally oriented and the tail moves up and down, unlike fish tails. The feature evolved by the time of basilosauridae and dorudontinae.

Feeding

The toothed whales, such as the sperm whale, beluga, dolphins, and porpoises, have teeth for catching fish, squid or other marine life. When a killer whales catch a seal, they bite off and swallow one chunk at a time.

Instead of teeth, the Mysticeti (Baleen whale) have baleen plates made of keratin (the same substance as human fingernails), which hang from the upper jaw. These plates filter small animals (such as krill and fish) from the seawater. Not all Mysticeti feed on plankton.

The larger Cetaceans, like the blue, humpback, bowhead, and minke whales, eat small shoaling fish, such as herring and sardines, called micronecton. The gray whale (Eschrichtius robustus), is a benthic feeder, primarily eating sea-floor crustaceans. Instead of preying on few species, Beluga whales are opportunistic feeders. They prey on about 100 different kinds of primarily bottom-dwelling animals. They eat octopus, squid, crabs, snails, sandworms, and fishes such as capelin, cod, herring, smelt, and flounder.

In terms of food intake, a blue whale eats up to 3,600 kg (8,000 lb) of krill each day for about 120 days while it is estimated to take 1,000 kg (2,200 lb) of food to fill a blue whale's stomach. Gray whales eat about 150,000 kg (340,000 lb) of food during a 130 to 140 day feeding period - a daily average intake of about 1,089 kg (2,400 lb.). It is estimated to take 300 kg (660 lb.) of food to fill a gray whale's stomach. Gray whales gain about 16% to 30% of their total body weight during a feeding season.[18]

Sexual Reproduction

Cetaceans evolved from land-dwelling ancestors and lost external hind limbs. They evolved significantly reduced pelvic bones that seemed to serve no other function except to anchor muscles that maneuver the penis. Cetacean pelvic bones are unique because they are no longer constrained by sacral and hind limb attachments or by hind limb locomotion.[19]

Cetacean pelvic bones were often thought of as “useless vestiges” of their land-dwelling ancestors.[20] However, they are a critical component of male reproductive fitness.

The paired pelvic bones anchor the genitalia and the paired ischiocavernosus muscles that control the penis.[21][22] In male cetaceans, the paired ischiocavernosus muscles insert deeply toward the distal end of the penis, while proximally encapsulating the paired crus of the penis that anchor to each pelvic bone.[23][24] The ischiocavernosus muscles appear to maneuver the penis by pulling it to one side or the other[25] and may also maintain erection by compressing the corpus cavernosusm proximally.[26] The ischiocavernosus muscles may work in coordination with other soft tissue innovacations to control the penis, which suggests the importance of ischiocavernosus muscles in penis movement.

Both size and shape of pelvic bones are evolutionary correlated to relative testes mass, which is a strong indication of postcopulatory sexual selection.[27][28] Male cetacean with relatively intense sexual selection tend to evolve larger penises and pelvic bones compared to their body length. The relative size of pelvic bones increases with relative testes mass. With PGLS (Phlogenetic generalized least squares) methodology, relative pelvic size was positively correlated with relative testes mass (phylogenetically controlled, P = 0.0006, r = 0.55), a pattern not observed in ribs.[19] Sexual Selection also appears to favor divergence in shape. Pelvic bone shape diverges more rapidly among species that have diverged in inferred mating system. According to analysis on pelvic and rib bones, pelvic bone shape divergence (independent of size) was positively correlated (Pearson’s correlation P = 0.003, r = 0.82). However such a relationship did not help explaining rib bones (Pearson’s correlation P = 0.98, r = -0.009).[19]

Taxonomy

Cetacea contains about 90 species, all marine except for four species of freshwater dolphins. Cetaceans can be divided into two further groups: Mysticeti (baleen whales) and Odontoceti (toothed whales, which includes dolphins, porpoises, and the Sperm Whale). The species range in size from Commerson's dolphin, smaller than a human, to the blue whale, the largest animal ever known to have lived.

Traditionally Cetacea was recognized as a unique order of mammals. However based on the molecular research and recent fossil discoveries show that cetaceans are nested within an other order of mammals, Artiodactyla, with a close relationship with the family Hippopotamidae[4][5][6][7][29][30][31][32][33][34] At least one author believes that Cetacea should be best recognized as an infraorder in the suborder Whippomorpha in Artiodactyla.[2]

| Artiodactyla |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

Mammalian characteristics include warm-bloodedness, breathing air through their lungs, suckling their young, and growing hair, although in the case of cetaceans, very little of it.

Another way of distinguishing a cetacean from a fish is the shape and orientation of the tail. Fish tails are vertical and move from side to side when the fish swims. A cetacean's tail — called a fluke — is horizontal and moves up and down, because cetacean spines bend in the same manner as a human spine.

Evolution

Cetacean (whales, dolphins and porpoises) evolution has one of the most complete fossil records, which makes tracking the intermediates between families easier. They are marine mammal relatives of the artiodactyl family Raoellidae, a group of land mammals characterized by an even-toed ungulate skull, slim limbs, and an ear with significant similarities to that of early whales.[35] One of these in particular, Indohyus, was characterized by a long snout and osteosclerosis, the second of which suggests that "Indohyus" was aquatic.[36] The terrestrial origins of cetaceans are indicated first by their need to breathe air from the surface, the bones of their fins, which resemble the limbs of land mammals, and by the vestigial remains of hind legs inherited from their four-legged ancestors. Loss of external hind limbs is particularly well documented and had been investigated to further explore the evolution of the families Pakicetidae, Ambulocetidae, Remingtonocetidae, Protocetidae, and Basilosauridae.

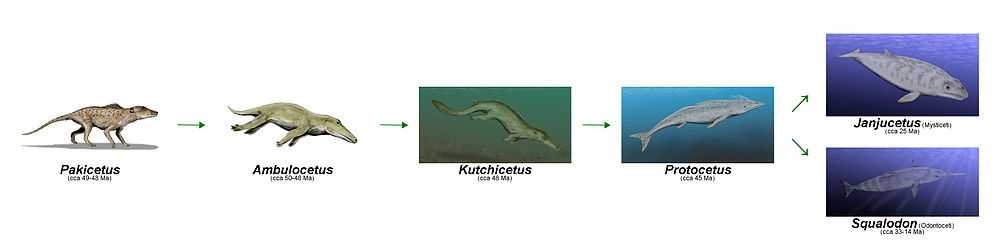

The question of how land animals became ocean-going was a mystery until discoveries starting in the late 1970s in Pakistan revealed several stages in the transition of cetaceans from land to sea:[37]

This image does not capture the true phylogenetic evolution of a particular species, but it is an illustrative representation of the evolution of cetaceans from terrestrial four-legged mammals, from their probable ancestor, through different stages of adaptation to aquatic life to modern cetaceans type, hydrodynamic body shape, fully developed caudal fin and vestigial hind legs. Although Pakicetidae still had weight supporting hind limbs, they are considered to be the first cetaceans and are not included in Artiodactylia.[38] This gave rise to Ambulocetidae whose strong tail suggested a life of more swimming.[39] Remingtonocetidae remained able to support its own weight but also developed a strong base for foot-powered swimming.[40] Protoceids were the first cetaceans to be found all over the world instead of simply Pakistan and India indicating more advanced aquatic locomotion. Two main genera are known: "Artiocetus" and "Georgiacetus." The first had reduced hind limbs but was still able to bear weight, while "Georgiacetus" had a pelvis which was completely disconnected from the spine, meaning it could not support its own weight and thus spent all of its time in water.[36] Basilosauridae were the first fully aquatic cetaceans. There were two main types, "Basilosaurus" and dorudontids. Both were characterized by tiny hind limbs, tail flukes, and an elongated vertebral column. This provided the foundation for the modern cetaceans mysticeti and odontoceti, respectively the suborders of baleen whales and toothed whales, a separation that occurred during the Oligocene (Janjucetus and Squalodon represent the early forms of their suborders).

Mysticeti vs Odontoceti

Fossils indicate, before evolving baleen, the Mysticeti also had teeth, so defining the Odontoceti by teeth alone is problematic. Instead, paleontologists have identified other features uniting fossil and modern odontocetes that are not shared by Mysticeti. It was also assumed that toothed whales evolved their asymmetrical skulls as an adaptation to their echolocation, but newer discoveries indicate the common ancestor of the present whales actually had a contorted skull, as well. Cranial asymmetry is now known to have evolved in ancient whales as part of a set of traits linked to directional hearing, including pan-bone thinning of the lower jaws, the development of mandibular fat pads, and the isolation of the ear region.[41] This likely means, while the asymmetry in the Odontoceti skull has increased over time, the Mysticeti skull has evolved from asymmetrical to symmetrical.[42]

| Characteristic | Odontoceti | Mysticeti |

| Feeding | Echolocation, fast | Filter feeder, not fast |

| Size | Smaller (except Sperm whale and beaked whale) | Larger (except pygmy right whale) |

| Blowhole | One | Two |

| Dentition | Teeth | Baleen plates |

| Melon | Ovoid, in anterior facial region | Vestigial or none |

| Skull and facial tissue | Dorsally asymmetric | Symmetric |

| Sexual dimorphism | Some species have larger males | Females always larger |

| Mandible | Symphyseal (fused anteriorly) | Nonsymphyseal |

| Pan bone of lower jaw | Yes | No |

| Maxillae projection | Outward over expanded supraorbital processes | Under eye orbit, with bony protuberance anterior to eye orbit |

| Olfactory nerve and bulb | Absent[43] | Vestigial[44] |

| Periotic bone | External to skull, fused with tympanic bulla | Fused with skull[45] |

Classification

The classification here closely follows Dale W. Rice, Marine Mammals of the World: Systematics and Distribution (1998), which has become the standard taxonomy reference in the field. There is very close agreement between this classification and that of Mammal Species of the World: 3rd Edition (Wilson and Reeder eds., 2005). Any differences are noted using the abbreviations "Rice"[46] and "MSW3"[1] respectively. Further differences due to recent discoveries are also noted.

Discussion of synonyms and subspecies are relegated to the relevant genus and species articles.

- ORDER CETACEA

- Suborder Mysticeti: Baleen whales

- Family Balaenidae: Right whales and bowhead whale

- Genus Balaena

- Bowhead whale, Balaena mysticetus

- Genus Eubalaena – Rice considered the three right whales as subspecies of Balaena glacialis

- North Atlantic right whale, Eubalaena glacialis

- North Pacific right whale, Eubalaena japonica

- Southern right whale, Eubalaena australis

- Genus Balaena

- Family Balaenopteridae: Rorquals

- Subfamily Balaenopterinae

- Genus Balaenoptera

- Common minke whale, Balaenoptera acutorostrata

- Antarctic minke whale, Balaenoptera bonaerensis

- Sei whale, Balaenoptera borealis

- Bryde's whale, Balaenoptera brydei

- Eden's whale Balaenoptera edeni – Rice lists this as a separate species, MSW3 does not

- Omura's whale – Balaenoptera omurai - MSW3 lists this is a synonym of Bryde's whale but suggests this may be temporary.

- Blue whale, Balaenoptera musculus

- Fin whale, Balaenoptera physalus

- Genus Balaenoptera

- Subfamily Megapterinae

- Genus Megaptera

- Humpback whale, Megaptera novaeangliae

- Genus Megaptera

- Subfamily Balaenopterinae

- Family Eschrichtiidae

- Genus Eschrichtius

- Gray whale, Eschrichtius robustus

- Genus Eschrichtius

- Family Cetotheriidae

- Genus Caperea

- Pygmy right whale, Caperea marginata

- Genus Caperea

- Family Balaenidae: Right whales and bowhead whale

- Suborder Odontoceti: toothed whales

- Family Delphinidae: Dolphin

- Genus Cephalorhynchus

- Commerson's dolphin, Cephalorhyncus commersonii

- Chilean dolphin, Cephalorhyncus eutropia

- Heaviside's dolphin, Cephalorhyncus heavisidii

- Hector's dolphin, Cephalorhyncus hectori

- Genus Delphinus

- Long-beaked common dolphin, Delphinus capensis

- Short-beaked common dolphin, Delphinus delphis

- Arabian common dolphin, Delphinus tropicalis. Rice recognises this as a separate species. MSW3 does not.

- Genus Feresa

- Pygmy killer whale, Feresa attenuata

- Genus Globicephala

- Short-finned pilot whale, Globicephala macrorhyncus

- Long-finned pilot whale, Globicephala melas

- Genus Grampus

- Risso's dolphin, Grampus griseus

- Genus Lagenodelphis

- Fraser's dolphin, Lagenodelphis hosei

- Genus Lagenorhynchus

- Atlantic white-sided dolphin, Lagenorhynchus acutus

- White-beaked dolphin, Lagenorhynchus albirostris

- Peale's dolphin, Lagenorhynchus australis

- Hourglass dolphin, Lagenorhynchus cruciger

- Pacific white-sided dolphin, Lagenorhynchus obliquidens

- Dusky dolphin, Lagenorhynchus obscurus

- Genus Lissodelphis

- Northern right whale dolphin, Lissodelphis borealis

- Southern right whale dolphin, Lissodelphis peronii

- Genus Orcaella

- Irrawaddy dolphin, Orcaella brevirostris

- Australian snubfin dolphin, Orcaella heinsohni A 2005 discovery, thus it is not recognized by Rice or MSW3 and subject to revision.

- Irrawaddy dolphin, Orcaella brevirostris

- Genus Orcinus

- Killer whale, Orcinus orca

- Genus Peponocephala

- Melon-headed whale, Peponocephala electra

- Genus Pseudorca

- False killer whale, Pseudorca crassidens

- Genus Sotalia

- Genus Sousa

- Pacific humpback dolphin, Sousa chinensis

- Indian humpback dolphin, Sousa plumbea

- Atlantic humpback dolphin, Sousa teuszii

- Genus Stenella

- Pantropical spotted dolphin, Stenella attenuata

- Clymene dolphin, Stenella clymene

- Striped dolphin, Stenella coeruleoalba

- Atlantic spotted dolphin, Stenella frontalis

- Spinner dolphin, Stenella longirostris

- Genus Steno

- Rough-toothed dolphin, Steno bredanensis

- Genus Tursiops – Rice and MSW3 tentatively agree on this classification

- Indian Ocean bottlenose dolphin, Tursiops aduncus

- Burrunan dolphin, Tursiops australis

- Common bottlenose dolphin, Tursiops truncatus

- Genus Cephalorhynchus

- Family Monodontidae

- Genus Delphinapterus

- Beluga, Delphinapterus leucas

- Genus Monodon

- Narwhal, Monodon monoceros

- Genus Delphinapterus

- Family Phocoenidae: Porpoises

- Genus Neophocaena

- Finless porpoise, Neophocaena phocaenoides

- Genus Phocoena

- Spectacled porpoise, Phocoena dioptrica

- Harbour porpoise, Phocoena phocaena

- Vaquita, Phocoena sinus

- Burmeister's porpoise, Phocoena spinipinnis

- Genus Phocoenoides

- Dall's porpoise, Phocoenoides dalli

- Genus Neophocaena

- Family Physeteridae: Sperm whale family

- Genus Physeter

- Sperm whale, Physeter catodon (syn. P. macrocephalus)

- Genus Physeter

- Family Kogiidae – MSW3 treats Kogia as a member of Physeteridae

- Genus Kogia

- Pygmy sperm whale, Kogia breviceps

- Dwarf sperm whale, Kogia sima

- Genus Kogia

- Superfamily Platanistoidea: River dolphins

- Family Iniidae

- Genus Inia

- Amazon river dolphin, Inia geoffrensis

- Bolivian river dolphin, Inia boliviensis (considered a sub-species of I. geoffrensis by much of the scientific community)

- Araguaian river dolphin. Inia araguaiaensis. A 2014 discovery, thus it is not recognized by Rice or MSW3 and subject to revision.

- Genus Inia

- Family Lipotidae – MSW3 treats Lipotes as a member of Iniidae

- Genus Lipotes

- Baiji, Lipotes vexillifer

- Genus Lipotes

- Family Pontoporiidae – MSW3 treats Pontoporia as a member of Iniidae

- Genus Pontoporia

- La Plata dolphin, Pontoporia blainvillei

- Genus Pontoporia

- Family Platanistidae

- Genus Platanista

- South Asian river dolphin, Platanista gangetica. MSW3 treats Platanista minor as a separate species, with common names Ganges River dolphin and Indus River dolphin, respectively.

- Genus Platanista

- Family Iniidae

- Superfamily Ziphioidea: Beaked whales

- Family Ziphidae,

- Genus Berardius

- Arnoux's beaked whale, Berardius arnuxii

- Baird's beaked whale (North Pacific bottlenose whale), Berardius bairdii

- Subfamily Hyperoodontidae

- Genus Hyperoodon

- Northern bottlenose whale, Hyperoodon ampullatus

- Southern bottlenose whale, Hyperoodon planifrons

- Genus Indopacetus

- Indo-Pacific beaked whale (Longman's beaked whale), Indopacetus pacificus

- Genus Mesoplodon, Mesoplodont whale

- Sowerby's beaked whale, Mesoplodon bidens

- Andrews' beaked whale, Mesoplodon bowdoini

- Hubbs' beaked whale, Mesoplodon carlhubbsi

- Blainville's beaked whale, Mesoplodon densirostris

- Gervais' beaked whale, Mesoplodon europaeus

- Ginkgo-toothed beaked whale, Mesoplodon ginkgodens

- Gray's beaked whale, Mesoplodon grayi

- Hector's beaked whale, Mesoplodon hectori

- Strap-toothed whale, Mesoplodon layardii

- True's beaked whale, Mesoplodon mirus

- Perrin's beaked whale, Mesoplodon perrini, recognized in 2002 and as such is listed by MSW3 but not Rice.

- Pygmy beaked whale, Mesoplodon peruvianus

- Stejneger's beaked whale, Mesoplodon stejnegeri

- Spade-toothed whale, Mesoplodon traversii

- Deraniyagala's beaked whale, Mesoplodon hotaula, recognized in 2014

- Genus Hyperoodon

- Genus Tasmacetus

- Shepherd's beaked whale, Tasmacetus shepherdi

- Genus Ziphius

- Cuvier's beaked whale, Ziphius cavirostris

- Genus Berardius

- Family Ziphidae,

- Family Delphinidae: Dolphin

- Suborder Mysticeti: Baleen whales

†Recently extinct

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Mead, J. G.; Brownell, R. L., Jr. (2005). "Order Cetacea". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. Mammal Species of the World (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 723–743. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Groves, Colin, and Peter Grubb. Ungulate taxonomy. JHU Press, 2011.

- ↑ "Whale Evolution".

- ↑ 4.0 4.1

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Boisserie, Jean-Renaud; Lihoreau, Fabrice and Brunet, Michel (2005). "The position of Hippopotamidae within Cetartiodactyla". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 102 (5): 1537–1541. Bibcode:2005PNAS..102.1537B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0409518102. PMC 547867. PMID 15677331.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Scientists find missing link between the dolphin, whale and its closest relative, the hippo". Science News Daily. 2005-01-25. Retrieved 2011-01-08.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "National Geographic – Hippo: Africa's River Beast". National Geographic. Retrieved 2007-07-18.

- ↑ "Dolphins deserve same rights as humans, say scientists". BBC News Online. 21 Feb 2012. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- ↑ "pod". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005.

- ↑ Castellini, Michael A.; Somero, George N. (1981). "Buffering capacity of vertebrate muscle: Correlations with potentials for anaerobic function". Journal of comparative physiology 143 (2): 191–198. doi:10.1007/BF00797698 (inactive 2015-03-30).

- ↑ Scholander, Per Fredrik (1940). "Experimental investigations on the respiratory function in diving mammals and birds". Hvalraadets Skrifter (Oslo: Norske Videnskaps-Akademi) 22.

- ↑ Thewissen, J. g. m. (2002). "Hearing". In Perrin, William R.; Wiirsig, Bernd; Thewissen, J. G. M. Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. Academic Press. pp. 570–2. ISBN 0-12-551340-2.

- ↑ Ketten, Darlene R. (1992). "The Marine Mammal Ear: Specializations for Aquatic Audition and Echolocation". In Webster, Douglas B.; Fay, Richard R.; Popper, Arthur N. The Evolutionary Biology of Hearing (PDF). Springer Verlag. pp. 717–50. Retrieved March 2013. Pages 725–7 used here.

- ↑ Hooker, Sascha K. (2009). Perrin, William F.; Wursig, Bernd; Thewissen, J. G. M., eds. Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals (2 ed.). 30 Corporate Drive, Burlington Ma. 01803: Academic Press. p. 1176. ISBN 978-0-12-373553-9.

- ↑ Sayigh, L.S. (2014). Cetacean Acoustic Communication. In: Witzany G (ed). Biocommunication of Animals. Springer. 275-297. ISBN 978-94-007-7413-1

- ↑ Ketten, Darlene R. (1997). "Structure and function in whale ears" (PDF). The International Journal of Animal Sound and its Recording 8 (1–2): 103–135. doi:10.1080/09524622.1997.9753356. Retrieved December 2013.

- ↑ Morell, Virginia (July 2011). "Guiana Dolphins Can Use Electric Signals to Locate Prey". Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). Retrieved December 2013.

- ↑ "Baleen Whales Diet & Eating Habits." Sea World. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Nov. 2014.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Dines, J. P., E. Otárola-Castillo, P. Ralph, J. Alas, T. Daley, A. D. Smith, and M. D. Dean. "Sexual Selection Targets Cetacean Pelvic Bones." Evolution (2014): N/a. Web.

- ↑ Curtis, H., and N. S. Barnes. 1989. Biology. 5th ed. Worth Publishers, New York.

- ↑ Struthers, J. 1881. On the bones, articulations, and muscles of the rudimentary hind limb of the Greenland Right-Whale (Balaena mysticetus). J. Anat. Physiol. 15:141–176

- ↑ Delage, Y. 1885. Histoire du Balaenoptera musculus echou e sur la Plage de Lagrune. Arch. Zool. Exp. Gen. (2me S ´ erie) 3:1–152.

- ↑ Ommanney, F. D. 1932. The urino-genital system in the fin whale. Discov.Rep. 5:363–466.

- ↑ Arvy, L. 1978. Le penis de C etac es. Mammalia 42:491–509.———. 1979. The abdominal bones of cetaceans. Invest. Cetacea 10:215– 227.

- ↑ Delage, Y. 1885. Histoire du Balaenoptera musculus echou e sur la Plage de Lagrune. Arch. Zool. Exp. Gen. (2me S ´ erie) 3:1–152.

- ↑ Ommanney, F. D. 1932. The urino-genital system in the fin whale. Discov. Rep. 5:363–466.

- ↑ Harcourt, A. H.; Harvey, P. H.; Larson, S. G.; Short, R. V. (1981). "Testis weight, body weight and breeding system in primates". Nature 293 (5827): 55–57. Bibcode:1981Natur.293...55H. doi:10.1038/293055a0. PMID 7266658.

- ↑ Kenagy, G. J., and S. C. Trombulak. 1986. Size and function of mammalian testes in relation to body size. J. Mammal. 67:1–22.

- ↑ University Of Michigan (2001, September 20). "New Fossils Suggest Whales And Hippos Are Close Kin". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 2007-12-21.

- ↑ Northeastern Ohio Universities Colleges of Medicine and Pharmacy (2007, December 21). "Whales Descended From Tiny Deer-like Ancestors". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 2007-12-21.

- ↑ Spaulding, M.; O'Leary, MA.; Gatesy, J. (2009). "Relationships of Cetacea (Artiodactyla) Among Mammals: Increased Taxon Sampling Alters Interpretations of Key Fossils and Character Evolution". PLoS ONE 4 (9): e7062. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.7062S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007062. PMC 2740860. PMID 19774069.

- ↑ Agnarsson, I.; May-Collado, LJ. (2008). "The phylogeny of Cetartiodactyla: the importance of dense taxon sampling, missing data, and the remarkable promise of cytochrome b to provide reliable species-level phylogenies.". Mol Phylogenet Evol. 48 (3): 964–985. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2008.05.046. PMID 18590827.

- ↑ Price, SA.; Bininda-Emonds, OR.; Gittleman, JL. (2005). "A complete phylogeny of the whales, dolphins and even-toed hoofed mammals (Cetartiodactyla).". Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 80 (3): 445–473. doi:10.1017/s1464793105006743. PMID 16094808.

- ↑ Montgelard, C.; Catzeflis, FM.; Douzery, E. (1997). "Phylogenetic relationships of artiodactyls and cetaceans as deduced from the comparison of cytochrome b and 12S RNA mitochondrial sequences". Molecular Biology and Evolution 14 (5): 550–559. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025792. PMID 9159933.

- ↑ Thewissen, JGM; Cooper, LN; Clementz, MT; Bajpai, S; Tiwari, BN (2007). "Whales originated from aquatic artiodactyls in the Eocene epoch of India" (PDF). Nature 450 (7173): 1190–4. Bibcode:2007Natur.450.1190T. doi:10.1038/nature06343. PMID 18097400. Retrieved February 2013.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Thewissen, J. G. M.; Cooper, Lisa Noelle; George, John C.; Bajpai, Sunil (16 April 2009). "From Land to Water: the Origin of Whales, Dolphins, and Porpoises". Evolution: Education and Outreach 2 (2): 272–288. doi:10.1007/s12052-009-0135-2.

- ↑ Gingerich, P.D. (Sep 2012). [<Go to ISI>://WOS:000315425000005 "Evolution of Whales from Land to Sea"]. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 156 (3). Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- ↑ Thewissen, J. G. M.; Williams, E. M.; Roe, L. J.; Hussain, S. T. (September 20, 2001). [<Go to ISI>://WOS:000171040500030 http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v413/n6853/pdf/413277a0.pdf "Skeletons of terrestrial cetaceans and the relationship of whales to artiodactyls"] (PDF). Nature 413 (6853): 277–81. Bibcode:2001Natur.413..277T. doi:10.1038/35095005. PMID 11565023. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ↑ Thewissenltos>

- ↑ Bebej, R. M.; ul-Haq, M.; Zalmout, I. S.; Gingerich, P. D. (June 2012). [Go to ISI>://WOS:000302697700001 "Morphology and Function of the Vertebral Column in Remingtonocetus domandaensis (Mammalia, cetacea) from the Middle Eocene Domanda Formation of Pakistan"]. Journal of Mammalian Evolution 19 (2): 77–104. doi:10.1007/S10914-011-9184-8. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ↑ Fahlke, Julia M.; Gingerich, Philip D.; Welsh, Robert C.; Wood, Aaron R. (2011). "Cranial asymmetry in Eocene archaeocete whales and the evolution of directional hearing in water". PNAS 108 (35): 14545–14548. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10814545F. doi:10.1073/pnas.1108927108. PMID 21873217.

- ↑ "Ancient Whales Had Twisted Skulls". LiveScience.com.

- ↑ "Dolphin Senses".

- ↑ SeaWorld Parks & Entertainment. "Baleen Whales: Senses".

- ↑ Hooker, Sascha K. (2009). "Toothed Whales. Overview". In Perrin, William F.; Wursig, Bernd; Thewissen, J. G. M. Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals (2 ed.). Burlington Ma. 01803: Academic Press. p. 1174. ISBN 978-0-12-373553-9.

- ↑ Rice, Dale W. (1998). Marine mammals of the world: systematics and distribution. Society of Marine Mammalogy, Special Publication No. 4. ISBN 1891276034.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to: Cetacea |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cetacea. |

| The Wikibook Dichotomous Key has a page on the topic of: Cetacea |

| Look up Cetacea in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- "Cetaceans". Encyclopedia of Earth. Retrieved February 2011.

- Scottish Cetacean Research & Rescue – see page on Taxonomy

- "Dolphin and Whale News". Science Daily. Retrieved March 2010.

- Futuyma, Douglas J. (1998). "Cetacea Evolution". Retrieved 2010.

- EIA Cetacean campaign: Reports and latest info.

- EIA in USA: reports etc.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||