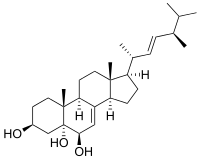

Cerevisterol

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

5α-Ergosta-7,22-diene-3β,5,6β-triol | |

| Other names

(22E)-Ergosta-7,22-diene-3β,5α,6β-triol;(22E)-5α-Ergosta-7,22-diene-3β,5,6β-triol;(22E,24R)-Ergosta-7,22-diene-3β,5α,6β-triol;(22E,24R)-5α-Ergosta-7,22-diene-3β,5,6β-triol;(22E,24R)-24-Methyl-5α-cholesta-7,22-diene-3β,5,6β-triol | |

| Identifiers | |

| 516-37-0 | |

| ChemSpider | 8356635 |

| Jmol-3D images | Image |

| PubChem | 10181133 |

| |

| Properties | |

| Molecular formula |

C26H46O3 |

| Molar mass | 406.64 g·mol−1 |

| Density | 1.086 g/ml |

| Melting point | 265.3 °C (509.5 °F; 538.5 K) |

| Except where noted otherwise, data is given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C (77 °F), 100 kPa) | |

| Infobox references | |

Cerevisterol (5α-ergosta-7,22-diene-3β,5,6β-triol) is a sterol. Originally described in the 1930s from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, it has since been found in several other fungi and, recently, in deep water coral. Cerevisterol has some in vitro bioactive properties, including cytotoxicity to some mammalian cell lines.

Discovery and properties

Cerevisterol was first discovered in 1928 as a component of crude yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) sterols remaining from the manufacture of the related ergosterol.[1] Chemists Edna M. Honeywell and Charles E. Bills purified the compound and reported some of its properties in a 1932 publication. They noted its high melting point (265.3 °C) relative to other sterols, and insolubility in the organic solvent hexane. These characteristics facilitated its purification, and they were able to obtain 10 grams (0.35 oz) of cerevisterol from 4,500 kilograms (9,900 lb) of dry yeast.[2] The following year, they determined its chemical formula to be C26H46O3, with two double bonds, and with two of the oxygen molecules occurring in hydroxyl groups.[3]

Its structure was determined in 1954 by comparison with a sample that was chemically synthesized from ergosterol.[4] Purified cerevisterol has the form of a white amorphous solid.[5] When crystallized in ethyl alcohol, it forms elongated prisms, while crystallization in acetone or ethyl acetate produces broad hexagonal prisms. Its UV absorption spectrum shows a maximum at about 248 nm. Cerevisterol is a stable molecule, showing no discoloration or change in melting point even after several weeks of exposure to light and air.[2]

Occurrence

Cerevisterol is widely distributed in the fungal kingdom. In the division Basidiomycota, it occurs in several members of the fungal family Boletaceae,[6] the edible mushrooms Cantharellus cibarius,[7] Volvariella volvacea,[8] Pleurotus sajor-caju,[9] Laetiporus sulphureus,[10] and Suillus luteus,[11] in the milk mushroom Lactarius hatsudake,[12] and the coral fungus Ramaria botrytis.[13] In the division Ascomycota, it has been reported in Auricularia polytricha,[14] Bulgaria inquinans,[15] Engleromyces goetzei,[16] Acremonium luzulae,[17] and Pencillium herquei,[18] as well as the lichens Ramalina hierrensis[19] and Stereocaulon azoreum.[20] It has also been found in the endophytes Alternaria brassicicola,[5] Fusarium oxysporum,[21] and a strain of Gliocladium,[22] and the deep-sea fungus Aspergillus sydowi.[23] In 2013, the sterol was reported in the South China Sea gorgonian coral Muriceoopsis flavida.[24] A 9-hydroxylated analogue of cerevisterol was found in R. botrytis.[13] A modified version of the compound, (22E, 24R)-cerevisterol, has been reported from the coral Subergorgia mollis. It was shown to be moderately cytotoxic to embryos of the zebrafish Danio rerio.[25]

Bioactivity

Cerevisterol inhibits the eukaryotic enzyme DNA polymerase alpha,[26] and it is also a potent inhibitor of NF-kappa B activation.[7] The sterol is cytotoxic to mouse P388 leukemia cells[23] and A549 human alveolar epithelial cells grown in culture.[24]

References

- ↑ Bills CE, Honeywell EM. (1928). "Antiricketic substances. VII. Studies on highly purified ergosterol and its esters" (PDF). Journal of Biological Chemistry 80: 15–23.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Honeywell EM, Bills CE. (1932). "Cerevisterol, a sterol accompanying ergosterol in yeast" (PDF). Journal of Biological Chemistry 99: 71–8.

- ↑ Honeywell EM, Bills CE. (1933). "Cerevisterol: New notes on composition, properties, and relation to other sterols" (PDF). Journal of Biological Chemistry 103: 515–20.

- ↑ Alt GN, Barton DHR. (1954). "The action of perphthalic acid on 5-dihydroergosteryl and ergosteryl acetates". Journal of the Chemical Society: 1356–61. doi:10.1039/JR9540001356.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Gu W. (2009). "Bioactive metabolites from Alternaria brassicicola ML-P08, an endophytic fungus residing in Malus halliana". World Journal of Microbiolal Biotechnology 25 (9): 1677–83. doi:10.1007/s11274-009-0062-y.

- ↑ Cherotch YP, Shivrina AN. (1973). "Cerevisterol in mushrooms of family Boletaceae". Doklady Akademii nauk SSSR (in Russian) 212 (4): 1015–6.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Kim JA, Tay D, de Blanco EC. (2008). "NF-κB inhibitory activity of compounds isolated from Cantharellus cibarius". Phytotherapy Research 22 (8): 1104–6. doi:10.1002/ptr.2467.

- ↑ Mallavadhani UV, Sudhakar AVS, Satyanarayana KVS, Mahapatra A, Li W, van Breemen RB. (2006). "Chemical and analytical screening of some edible mushrooms". Food Chemistry 95 (1): 58–64. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2004.12.018.

- ↑ Nieto IJ, Chegwin C. (2008). "Triterpenoids and fatty acids identified in the edible mushroom Pleurotus sajor-cajú". Journal of the Chilean Chemical Society 53 (2): 1515–7. doi:10.4067/S0717-97072008000200015.

- ↑ Coy ED, Nieto IJ. (2009). "Sterol composition of the macromycete fungus Laetiporus sulphureus". Chemistry of Natural Compounds 45 (2): 193–6. doi:10.1007/s10600-009-9301-6.

- ↑ Leon F, Brouard I, Torres F, Quintana J, Rivera A, Estevez F, Bermejo J. (2008). "A new ceramide from Suillus luteus and its cytotoxic activity against human melanoma cells". Chemistry and Biodiversity 5 (1): 120–5. doi:10.1002/cbdv.200890002.

- ↑ Gao JM, Wang M, Wei GH, Zhang AL, Draghici C, Konishi Y. (2007). "Ergosterol peroxides as phospholipase A2 inhibitors from the fungus Lactarius hatsudake". Phytomedicine 14 (12): 821–4. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2006.12.006.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Yaoita Y, Satoh Y, Kikuchi M. (2007). "A new ceramide from Ramaria botrytis (Pers.) Ricken". Journal of Natural Medicine 61 (2): 205–7. doi:10.1007/s11418-006-0121-8.

- ↑ Koyama K, Akiba M, Imaizumi T, Kinoshite K, Takahashi K, Suzuki A, Yano S, Horie S, Watanabe K. (2002). "Antinociceptive constituents of Auricularia polytricha". Planta Medica 68 (3): 284–5. doi:10.1055/s-2002-23141.

- ↑ Zhang P, Li M, Li N, Xu J, Li ZL, Wang Y, Wang JH. (2005). "Antibacterial constituents from fruit bodies of ascomycete Bulgaria inquinans". Archives of Pharmacal Research 28 (8): 889–91. doi:10.1007/BF02973872.

- ↑ Zhan ZJ, Sun HD, Wu HM, Yue JM. (2003). "Chemical components from the fungus Engleromyces goetzei". Acta Botanica Sinica 45 (2): 248–52.

- ↑ Ceccherelli P, Fringuelli R, Madruzza GF. (1975). "Cerevisterol and ergosterol peroxide from Acremonium luzulae". Phytochemistry 14 (5–6): 1434. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(00)98646-1.

- ↑ Marinho AMD, Marinho PSB, Rodrigues E. (2009). "Steroids produced by Penicillium herquei, an endophytic fungus isolated from the fruits of Melia azedarach (Meliaceae)". Quimica Nova (in Portuguese) 32 (7): 1710–2. doi:10.1590/s0100-40422009000700005.

- ↑ Gonzalez AG, Barrera JB, Perez EMR, Padron CEH. (1992). "Chemical constituents of the lichen Ramalina hierrensis". Planta Medica 58 (2): 214–8. doi:10.1055/s-2006-961433.

- ↑ Gonzalez AG, Perez EMR, Padron CEH, Barrera JB. (1992). "Chemical constituents of the lichen Sterocaulon azoreum". Zeitschrift für Naturforschung. C, Journal of biosciences 47 (7–8): 503–7.

- ↑ Wang QX, Li SF, Zhao F, Dai HQ, Bao L, Ding R, Gao H, Zhang LX, Wen HA, Liu HW. (2011). "Chemical constituents from endophytic fungus Fusarium oxysporum" (PDF). Fitoterapia 82 (5): 777–81. doi:10.1016/j.fitote.2011.04.002. PMID 21497643.

- ↑ Koolen HH, Soares ER, Silva FM, Souza AQ, Medeiros LS, Filho ER, Almeida RA, Ribeiro IA, Pessoa Cdo Ó, Morais MO, Costa PM, Souza AD. (2012). "An antimicrobial diketopiperazine alkaloid and co-metabolites from an endophytic strain of Gliocladium isolated from Strychnos cf. toxifera". Natural Products Research 26 (21): 2013–9. doi:10.1080/14786419.2011.639070. PMID 22117164.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Li D-H, Cai S-X, Tian L, Lin Z-J, Zhu T-J, Fang Y-C, Liu P-P, Gu Q-Q, Zhu W-M. (2007). "Two new metabolites with cytotoxicities from deep-sea fungus Aspergillus sydowi YH11-2". Archives of Pharmacal Research 30 (9): 1051–4. doi:10.1007/BF02980236.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Liu TF, Lu X, Tang H, Zhang MM, Wang P, Sun P, Liu ZY, Wang ZL, Li L, Rui YC, Li TJ, Zhang W. (2013). "3β,5α,6β-Oxygenated sterols from the South China Sea gorgonian Muriceopsis flavida and their tumor cell growth inhibitory activity and apoptosis-inducing function". Steroids 78 (1): 108–14. doi:10.1016/j.steroids.2012.10.003. PMID 23123740.

- ↑ Kong W-W, Shao C-L, Wang C-Y, Xu Y, Qian P-Y, Chen A-N, Huang H. (2012). "Diterpneoids and steroids from gorgonian Subergorgia mollis". Chemistry of Natural Compounds 48 (3): 512–5. doi:10.1007/s10600-012-0294-1.

- ↑ Mizushina Y, Takahashi N, Hanashima L, Koshino H, Esumi Y, Uzawa J J, Sugawara F, Sakaguchi K. (1999). "Lucidenic acid O and lactone, new terpene inhibitors of eukaryotic DNA polymerases from a basidiomycete, Ganoderma lucidum". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 7 (9): 2047–52. doi:10.1016/S0968-0896(99)00121-2.