Ceres (dwarf planet)

|

| |||||||||

| Discovery[1] | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discovered by | Giuseppe Piazzi | ||||||||

| Discovery date | 1 January 1801 | ||||||||

| Designations | |||||||||

| MPC designation | 1 Ceres | ||||||||

| Pronunciation | /ˈsɪəriːz/ | ||||||||

Named after | Cerēs | ||||||||

| A899 OF; 1943 XB | |||||||||

|

dwarf planet main belt | |||||||||

| Adjectives |

Cererian /sɨˈrɪəri.ən/, rarely Cererean /sɛrɨˈriːən/[2] | ||||||||

| Orbital characteristics[3] | |||||||||

|

Epoch 2014-Dec-09 (JD 2457000.5) | |||||||||

| Aphelion |

2.9773 AU (445410000 km) | ||||||||

| Perihelion |

2.5577 AU (382620000 km) | ||||||||

|

2.7675 AU (414010000 km) | |||||||||

| Eccentricity | 0.075823 | ||||||||

|

4.60 yr 1681.63 d | |||||||||

|

466.6 d 1.278 yr | |||||||||

Average orbital speed | 17.905 km/s | ||||||||

| 95.9891° | |||||||||

| Inclination |

10.593° to ecliptic 9.20° to invariable plane[4] | ||||||||

| 80.3293° | |||||||||

| 72.5220° | |||||||||

| Satellites | None | ||||||||

| Proper orbital elements[5] | |||||||||

Proper semi-major axis | 2.7670962 AU | ||||||||

Proper eccentricity | 0.1161977 | ||||||||

Proper inclination | 9.6474122° | ||||||||

Proper mean motion | 78.193318 deg / yr | ||||||||

Proper orbital period |

4.60397 yr (1681.601 d) | ||||||||

Precession of perihelion | 54.070272 arcsec / yr | ||||||||

Precession of the ascending node | −59.170034 arcsec / yr | ||||||||

| Physical characteristics | |||||||||

Mean radius | 476.2±1.7 km | ||||||||

Equatorial radius | 487.3±1.8 km[6] | ||||||||

Polar radius | 454.7±1.6 km[6] | ||||||||

| 2850000 km2 | |||||||||

| Mass |

(9.43±0.07)×1020 kg,[7] 9.47±?[8] 0.0128 Moons | ||||||||

Mean density | 2.077±0.036 g/cm3,[6] 2.09±?[8] | ||||||||

|

0.28 m/s2[8] 0.029 g | |||||||||

| 0.51 km/s[9] | |||||||||

Sidereal rotation period |

0.3781 d 9.074170±0.000002 h[10] | ||||||||

| ≈ 3°[6] | |||||||||

North pole right ascension |

19h 24m 291°[6] | ||||||||

North pole declination | 59°[6] | ||||||||

| Albedo | 0.090±0.0033 (V-band geometric)[11] | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Spectral type | C[14] | ||||||||

| 6.64[15] to 9.34[16] | |||||||||

| 3.36±0.02[11] | |||||||||

| 0.854″ to 0.339″ | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

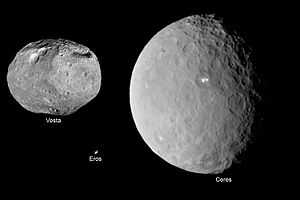

Ceres (/ˈsɪəriːz/;[17] minor-planet designation: 1 Ceres) is the largest object in the asteroid belt, which lies between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. It is composed of rock and ice, is 950 kilometers (590 miles) in diameter, and comprises approximately one third of the mass of the asteroid belt. It is the only dwarf planet in the inner Solar System and the only object in the asteroid belt known to be unambiguously rounded by its own gravity. It was the first asteroid to be discovered, on 1 January 1801 by Giuseppe Piazzi in Palermo, though at first it was considered a planet. From Earth, the apparent magnitude of Ceres ranges from 6.7 to 9.3, and hence even at its brightest it is too dim to be seen with the naked eye except under extremely dark skies.

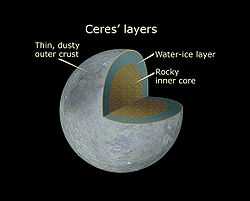

Ceres appears to be differentiated into a rocky core and icy mantle, and may harbor a remnant internal ocean of liquid water under the layer of ice.[18][19] The surface is probably a mixture of water ice and various hydrated minerals such as carbonates and clay. In January 2014, emissions of water vapor were detected from several regions of Ceres.[20] This was somewhat unexpected, because large bodies in the asteroid belt do not typically emit vapor, a hallmark of comets.

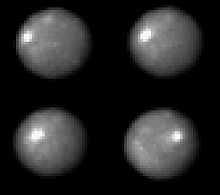

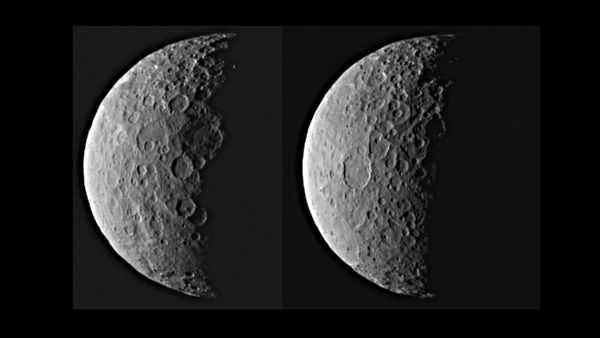

The robotic NASA spacecraft Dawn entered orbit around Ceres on 6 March 2015.[21][22][23] Pictures with previously unattained resolution were taken during imaging sessions starting in January 2015 as Dawn approached Ceres, showing a cratered surface. A bright spot seen in earlier Hubble images was resolved as two distinct high-albedo features inside a crater in a 19 February 2015 image, leading to speculation about a possible cryovolcanic origin[24][25][26] or outgassing.[27] On 3 March 2015, a NASA spokesperson said the spots are consistent with highly reflective materials containing ice or salts, but that cryovolcanism is unlikely.[28]

Discovery

Johann Elert Bode, in 1772, first suggested that an undiscovered planet could exist between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter.[29] Kepler had already noticed the gap between Mars and Jupiter in 1596.[29] Bode based his idea on the Titius–Bode law—a now-discredited hypothesis Johann Daniel Titius first proposed in 1766—observing that there was a regular pattern in the semi-major axes of the orbits of known planets, marred only by the large gap between Mars and Jupiter.[29][30] The pattern predicted that the missing planet ought to have an orbit with a semi-major axis near 2.8 astronomical units (AU).[30] William Herschel's discovery of Uranus in 1781[29] near the predicted distance for the next body beyond Saturn increased faith in the law of Titius and Bode, and in 1800, a group headed by Franz Xaver von Zach, editor of the Monatliche Correspondenz, sent requests to twenty-four experienced astronomers (dubbed the "celestial police"), asking that they combine their efforts and begin a methodical search for the expected planet.[29][30] Although they did not discover Ceres, they later found several large asteroids.[30]

One of the astronomers selected for the search was Giuseppe Piazzi at the Academy of Palermo, Sicily. Before receiving his invitation to join the group, Piazzi discovered Ceres on 1 January 1801.[31] He was searching for "the 87th [star] of the Catalogue of the Zodiacal stars of Mr la Caille", but found that "it was preceded by another".[29] Instead of a star, Piazzi had found a moving star-like object, which he first thought was a comet.[32] Piazzi observed Ceres a total of 24 times, the final time on 11 February 1801, when illness interrupted his observations. He announced his discovery on 24 January 1801 in letters to only two fellow astronomers, his compatriot Barnaba Oriani of Milan and Bode of Berlin.[33] He reported it as a comet but "since its movement is so slow and rather uniform, it has occurred to me several times that it might be something better than a comet".[29] In April, Piazzi sent his complete observations to Oriani, Bode, and Jérôme Lalande in Paris. The information was published in the September 1801 issue of the Monatliche Correspondenz.[32]

By this time, the apparent position of Ceres had changed (mostly due to Earth's orbital motion), and was too close to the Sun's glare for other astronomers to confirm Piazzi's observations. Toward the end of the year, Ceres should have been visible again, but after such a long time it was difficult to predict its exact position. To recover Ceres, Carl Friedrich Gauss, then 24 years old, developed an efficient method of orbit determination.[32] In only a few weeks, he predicted the path of Ceres and sent his results to von Zach. On 31 December 1801, von Zach and Heinrich W. M. Olbers found Ceres near the predicted position and thus recovered it.[32]

The early observers were only able to calculate the size of Ceres to within about an order of magnitude. Herschel underestimated its diameter as 260 km in 1802, whereas in 1811 Johann Hieronymus Schröter overestimated it as 2,613 km.[34][35]

Name

Piazzi originally suggested the name Cerere Ferdinandea for his discovery, after the goddess Ceres (Roman goddess of agriculture, Cerere in Italian, who was believed to have originated in Sicily and whose oldest temple was there) and King Ferdinand of Sicily.[29][32] "Ferdinandea", however, was not acceptable to other nations and was dropped. Ceres was called Hera for a short time in Germany.[36] In Greece, it is called Demeter (Δήμητρα), after the Greek equivalent of the Roman Cerēs;[lower-alpha 1] in English, that name is used for the asteroid 1108 Demeter.

The regular adjectival forms of the name are Cererian and Cererean,[37] derived from the Latin genitive Cereris,[2] but Ceresian is occasionally seen for the goddess (as in the sickle-shaped Ceresian Lake), as is the shorter form Cerean.

The old astronomical symbol of Ceres is a sickle, ⟨⚳⟩ (![]() ),[38] similar to Venus's symbol ⟨♀⟩ but with a break in the circle. It has a variant ⟨

),[38] similar to Venus's symbol ⟨♀⟩ but with a break in the circle. It has a variant ⟨ ![]() ⟩, reversed under the influence of the initial letter 'C' of 'Ceres'. These were later replaced with the generic asteroid symbol of a numbered disk, ⟨①⟩.[32][39]

⟩, reversed under the influence of the initial letter 'C' of 'Ceres'. These were later replaced with the generic asteroid symbol of a numbered disk, ⟨①⟩.[32][39]

The chemical element cerium, discovered in 1803, was named after Ceres.[40][lower-alpha 2] In the same year another element was also initially named after Ceres, but when cerium was named its discoverer changed the name to palladium, after the second asteroid, 2 Pallas.[42]

Classification

The categorization of Ceres has changed more than once and has been the subject of some disagreement. Johann Elert Bode believed Ceres to be the "missing planet" he had proposed to exist between Mars and Jupiter, at a distance of 419 million km (2.8 AU) from the Sun.[29] Ceres was assigned a planetary symbol, and remained listed as a planet in astronomy books and tables (along with 2 Pallas, 3 Juno, and 4 Vesta) for half a century.[29][32][43]

As other objects were discovered in the neighborhood of Ceres, it was realized that Ceres represented the first of a new class of objects.[29] In 1802, with the discovery of 2 Pallas, William Herschel coined the term asteroid ("star-like") for these bodies,[43] writing that "they resemble small stars so much as hardly to be distinguished from them, even by very good telescopes".[44] As the first such body to be discovered, Ceres was given the designation 1 Ceres under the modern system of minor-planet designations. By the 1860s, the existence of a fundamental difference between asteroids such as Ceres and the major planets was widely accepted, though a precise definition of "planet" was never formulated.[43]

The 2006 debate surrounding Pluto and what constitutes a planet led to Ceres being considered for reclassification as a planet.[45][46] A proposal before the International Astronomical Union for the definition of a planet would have defined a planet as "a celestial body that (a) has sufficient mass for its self-gravity to overcome rigid-body forces so that it assumes a hydrostatic equilibrium (nearly round) shape, and (b) is in orbit around a star, and is neither a star nor a satellite of a planet".[47] Had this resolution been adopted, it would have made Ceres the fifth planet in order from the Sun.[48] This never happened, however, and on 24 August 2006 a modified definition was adopted, carrying the additional requirement that a planet must have "cleared the neighborhood around its orbit". By this definition, Ceres is not a planet because it does not dominate its orbit, sharing it as it does with the thousands of other asteroids in the asteroid belt and constituting only about a third of the mass of the belt. Bodies that met the first proposed definition but not the second, such as Ceres, were instead classified as dwarf planets.

Ceres is the largest object in the asteroid belt.[14] It is sometimes assumed that Ceres has been reclassified as a dwarf planet, and that it is therefore no longer considered an asteroid. For example, a news update at Space.com spoke of "Pallas, the largest asteroid, and Ceres, the dwarf planet formerly classified as an asteroid",[49] whereas an IAU question-and-answer posting states, "Ceres is (or now we can say it was) the largest asteroid", though it then speaks of "other asteroids" crossing Ceres's path and otherwise implies that Ceres is still considered an asteroid.[50] The Minor Planet Center notes that such bodies may have dual designations.[51] The 2006 IAU decision that classified Ceres as a dwarf planet never addressed whether it is or is not an asteroid. Indeed, the IAU has never defined the word 'asteroid' at all, having preferred the term 'minor planet' until 2006, and preferring the terms 'small Solar System body' and 'dwarf planet' after 2006. Lang (2011) comments "the [IAU has] added a new designation to Ceres, classifying it as a dwarf planet. ... By [its] definition, Eris, Haumea, Makemake and Pluto, as well as the largest asteroid, 1 Ceres, are all dwarf planets", and describes it elsewhere as "the dwarf planet–asteroid 1 Ceres".[52] NASA continues to refer to Ceres as an asteroid,[53] as do various academic textbooks.[54][55]

Physical characteristics

The mass of Ceres has been determined by analysis of the influence it exerts on smaller asteroids. Results differ slightly between researchers.[56] The average of the three most precise values as of 2008 is 9.4×1020 kg.[7][56] With this mass Ceres comprises about a third of the estimated total 3.0 ± 0.2×1021 kg mass of the asteroid belt,[57] which is in turn about 4% of the mass of the Moon. The mass of Ceres is sufficient to give it a nearly spherical shape in hydrostatic equilibrium.[6] Among Solar System bodies, Ceres is intermediate in size between the smaller Orcus and 2002 MS4 and the larger Tethys. The surface area is approximately equal to the land area of India or Argentina.[58]

| Ceres - dwarf planet |

|---|

|

Internal structure

Ceres's oblateness is consistent with a differentiated body, a rocky core overlain with an icy mantle.[6] This 100-kilometer-thick mantle (23%–28% of Ceres by mass; 50% by volume)[59] contains 200 million cubic kilometers of water, which is more than the amount of fresh water on Earth.[60] This result is supported by the observations made by the Keck telescope in 2002 and by evolutionary modeling.[7][18] Also, some characteristics of its surface and history (such as its distance from the Sun, which weakened solar radiation enough to allow some fairly low-freezing-point components to be incorporated during its formation), point to the presence of volatile materials in the interior of Ceres.[7] It has been suggested that a remnant layer of liquid water may have survived to the present under a layer of ice.[18][19]

Alternatively, the shape and dimensions of Ceres may be explained by an interior that is porous and either partially differentiated or completely undifferentiated. The presence of a layer of rock on top of ice would be gravitationally unstable. If any of the rock deposits sank into a layer of differentiated ice, salt deposits would be formed. Such deposits have not been detected. Thus it is possible that Ceres does not contain a large ice shell, but was instead formed from low-density asteroids with an aqueous component. The decay of radioactive isotopes may not have produced sufficient heat to cause differentiation.[61]

Surface

The surface composition of Ceres is broadly similar to that of C-type asteroids.[14] Some differences do exist. The ubiquitous features in Ceres's IR spectrum are those of hydrated materials, which indicate the presence of significant amounts of water in its interior. Other possible surface constituents include iron-rich clay minerals (cronstedtite) and carbonate minerals (dolomite and siderite), which are common minerals in carbonaceous chondrite meteorites.[14] The spectral features of carbonates and clay minerals are usually absent in the spectra of other C-type asteroids.[14] Sometimes Ceres is classified as a G-type asteroid.[62]

The Cererian surface is relatively warm. The maximum temperature with the Sun overhead was estimated from measurements to be 235 K (about −38 °C, −36 °F) on 5 May 1991.[13] Ice is unstable at this temperature. Material left behind by the sublimation of surface ice could explain the dark surface of Ceres compared to the icy moons of the outer Solar System.

Observations prior to Dawn

Prior to the Dawn mission, only a few surface features had been unambiguously detected on Ceres. High-resolution ultraviolet Hubble Space Telescope images taken in 1995 showed a dark spot on its surface, which was nicknamed "Piazzi" in honor of the discoverer of Ceres.[62] This was thought to be a crater. Later near-infrared images with a higher resolution taken over a whole rotation with the Keck telescope using adaptive optics showed several bright and dark features moving with Ceres's rotation.[7][63] Two dark features had circular shapes and are presumably craters; one of them was observed to have a bright central region, whereas another was identified as the "Piazzi" feature.[7][63] Visible-light Hubble Space Telescope images of a full rotation taken in 2003 and 2004 showed 11 recognizable surface features, the natures of which are yet undetermined.[11][64] One of these features corresponds to the "Piazzi" feature observed earlier.[11]

These last observations also determined that the north pole of Ceres points in the direction of right ascension 19 h 24 min (291°), declination +59°, in the constellation Draco. This means that Ceres's axial tilt is very small—about 3°.[6][11]

Observations by Dawn

Dawn revealed a large number of craters with low relief, indicating that they lie over a relatively soft surface, probably of water ice. One crater, with extremely low relief, is 270 km in diameter,[65] reminiscent of large, flat craters on Tethys and Iapetus. Several bright spots have been observed by Dawn; the brightest of them was already known from earlier Hubble images. When Dawn entered orbit around Ceres, the brightest spot was still too small to be resolved (meaning that it was less than one pixel, or 4 km, across), but Dawn was able to discern a second, somewhat dimmer spot located next to it. It was also revealed that the brightest spot was sitting in the middle of an 80 km crater, with its dimmer companion located towards this crater's eastern rim. In images not released to the public, these bright spots could already be seen when the crater rim should still be in the line of sight. This would mean that they are located above the craters, suggesting some kind of outgassing. Moreover, the spots brighten during the day and get fainter at dusk.[66] These bright features have an albedo of about 40%.[67]

| Ceres - dwarf planet |

|---|

region "1" (top row) ("cooler" than surroundings); region "5" (bottom) ("similar in temperature" as surroundings) (April 2015). |

| Ceres - bright spots - region "5" |

|---|

from 22,000 km (14,000 mi) on 14 April 2015 |

Atmosphere

There are indications that Ceres may have a tenuous atmosphere and water frost on the surface.[68] Surface water ice is unstable at distances less than 5 AU from the Sun,[69] so it is expected to sublime if it is exposed directly to solar radiation. Water ice can migrate from the deep layers of Ceres to the surface, but escapes in a very short time. As a result, it is difficult to detect water vaporization. Water escaping from polar regions of Ceres was possibly observed in the early 1990s but this has not been unambiguously demonstrated. It may be possible to detect escaping water from the surroundings of a fresh impact crater or from cracks in the subsurface layers of Ceres.[7] Ultraviolet observations by the IUE spacecraft detected statistically significant amounts of hydroxide ions near the Cererean north pole, which is a product of water-vapor dissociation by ultraviolet solar radiation.[68]

In early 2014, using data from the Herschel Space Observatory, it was discovered that there are several localized (not more than 60 km in diameter) mid-latitude sources of water vapor on Ceres, which each give off about 1026 molecules (or 3 kg) of water per second.[70][71][lower-alpha 3] Two potential source regions, designated Piazzi (123°E, 21°N) and Region A (231°E, 23°N), have been visualized in the near infrared as dark areas (Region A also has a bright center) by the W. M. Keck Observatory. Possible mechanisms for the vapor release are sublimation from about 0.6 km2 of exposed surface ice, or cryovolcanic eruptions resulting from radiogenic internal heat[70] or from pressurization of a subsurface ocean due to growth of an overlying layer of ice.[19] Surface sublimation would be expected to decline as Ceres recedes from the Sun in its eccentric orbit, whereas internally powered emissions should not be affected by orbital position. The limited data available are more consistent with cometary-style sublimation.[70] The spacecraft Dawn is approaching Ceres at aphelion, which may constrain Dawn's ability to observe this phenomenon.[70]

Potential habitability

Although not as actively discussed as a potential home for microbial extraterrestrial life as Mars, Titan, Europa or Enceladus, the presence of water ice has led to speculation that life may exist there,[74][75][76] and that hypothesized ejecta could have come from Ceres to Earth.[77]

Orbit

| Element type | a (in AU) | e | i | Period (in days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proper[5] | 2.7671 | 0.116198 | 9.647435 | 1681.60 |

| Osculating[3] (Epoch 2010-Jul-23) | 2.7653 | 0.079138 | 10.586821 | 1679.66 |

| Difference | 0.0018 | 0.03706 | 0.939386 | 1.94 |

Ceres follows an orbit between Mars and Jupiter, within the asteroid belt, with a period of 4.6 Earth years.[3] The orbit is moderately inclined (i = 10.6° compared to 7° for Mercury and 17° for Pluto) and moderately eccentric (e = 0.08 compared to 0.09 for Mars).[3]

The diagram illustrates the orbits of Ceres (blue) and several planets (white and gray). The segments of orbits below the ecliptic are plotted in darker colors, and the orange plus sign is the Sun's location. The top left diagram is a polar view that shows the location of Ceres in the gap between Mars and Jupiter. The top right is a close-up demonstrating the locations of the perihelia (q) and aphelia (Q) of Ceres and Mars. In this diagram (but not in general), the perihelion of Mars is on the opposite side of the Sun from those of Ceres and several of the large main-belt asteroids, including 2 Pallas and 10 Hygiea. The bottom diagram is a side view showing the inclination of the orbit of Ceres compared to the orbits of Mars and Jupiter.

Ceres was once thought to be a member of an asteroid family.[78] The asteroids of this family share similar proper orbital elements, which may indicate a common origin through an asteroid collision some time in the past. Ceres was later found to have spectral properties different from other members of the family, which is now called the Gefion family after the next-lowest-numbered family member, 1272 Gefion.[78] Ceres appears to be merely an interloper in the Gefion family, coincidentally having similar orbital elements but not a common origin.[79]

The rotational period of Ceres (the Cererian day) is 9 hours and 4 minutes.[80]

Ceres is in a near-1:1 mean-motion orbital resonance with Pallas (their proper orbital periods differ by 0.2%).[81] However, a true resonance between the two would be unlikely; due to their small masses relative to their large separations, such relationships among asteroids are very rare.[82] Nevertheless, Ceres is able to capture other asteroids into temporary 1:1 resonant orbital relationships (for periods up to 2 million years or more); 51 such objects have been identified.[83]

Transits of planets from Ceres

Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars can all appear to cross the Sun, or transit it, from a vantage point on Ceres. The most common transits are those of Mercury, which usually happen every few years, most recently in 2006 and 2010. The most recent transit of Venus was in 1953, and the next will be in 2051; the corresponding dates are 1814 and 2081 for transits of Earth, and 767 and 2684 for transits of Mars.[84]

Origin and evolution

Ceres is probably a surviving protoplanet (planetary embryo), which formed 4.57 billion years ago in the asteroid belt.[18] Although the majority of inner Solar System protoplanets (including all lunar- to Mars-sized bodies) either merged with other protoplanets to form terrestrial planets or were ejected from the Solar System by Jupiter,[85] Ceres is believed to have survived relatively intact.[18] An alternative theory proposes that Ceres formed in the Kuiper belt and later migrated to the asteroid belt.[86] Another possible protoplanet, Vesta, is less than half the size of Ceres; it suffered a major impact after solidifying, losing ~1% of its mass.[87]

The geological evolution of Ceres was dependent on the heat sources available during and after its formation: friction from planetesimal accretion, and decay of various radionuclides (possibly including short-lived isotopes such as the cosmogenic nuclide aluminium-26). These are thought to have been sufficient to allow Ceres to differentiate into a rocky core and icy mantle soon after its formation.[11][18] This process may have caused resurfacing by water volcanism and tectonics, erasing older geological features.[18] Due to its small size, Ceres would have cooled early in its existence, causing all geological resurfacing processes to cease.[18][88] Any ice on the surface would have gradually sublimated, leaving behind various hydrated minerals like clay minerals and carbonates.[14]

Today, Ceres appears to be a geologically inactive body, with a surface sculpted only by impacts.[11] The presence of significant amounts of water ice in its composition[6] raises the possibility that Ceres has or had a layer of liquid water in its interior.[18][88] This hypothetical layer is often called an ocean.[14] If such a layer of liquid water exists, it is believed to be located between the rocky core and ice mantle like that of the theorized ocean on Europa.[18] The existence of an ocean is more likely if solutes (i.e. salts), ammonia, sulfuric acid or other antifreeze compounds are dissolved in the water.[18]

Observation

When Ceres has an opposition near the perihelion, it can reach a visual magnitude of +6.7.[15] This is generally regarded as too dim to be seen with the naked eye, but under exceptional viewing conditions a very sharp-sighted person may be able to see it. Ceres was at its brightest (6.73) on 18 December 2012.[16] The only other asteroids that can reach a similarly bright magnitude are 4 Vesta, and, during rare oppositions near perihelion, 2 Pallas and 7 Iris.[89] At a conjunction Ceres has a magnitude of around +9.3, which corresponds to the faintest objects visible with 10×50 binoculars. It can thus be seen with binoculars whenever it is above the horizon of a fully dark sky.

Some notable observations and milestones for Ceres include:

- 1984 November 13: An occultation of a star by Ceres observed in Mexico, Florida and across the Caribbean .[90]

- 1995 June 25: Ultraviolet Hubble Space Telescope images with 50 km resolution.[62][91]

- 2002: Infrared images with 30 km resolution taken with the Keck telescope using adaptive optics.[63]

- 2003 and 2004: Visible light images with 30 km resolution (the best prior to the Dawn mission) taken using Hubble.[11][64]

- 2012 December 22: Ceres occulted the star TYC 1865-00446-1 over parts of Japan, Russia, and China.[92] Ceres's brightness was magnitude 6.9 and the star, 12.2.[92]

- 2014: Ceres was found to have an atmosphere with water vapor, confirmed by the Herschel space telescope.[93]

- 2015: The NASA Dawn spacecraft approached and orbited Ceres.

Exploration

In 1981, a proposal for an asteroid mission was submitted to the European Space Agency (ESA). Named the Asteroidal Gravity Optical and Radar Analysis (AGORA), this spacecraft was to launch some time in 1990–1994 and perform two flybys of large asteroids. The preferred target for this mission was Vesta. AGORA would reach the asteroid belt either by a gravitational slingshot trajectory past Mars or by means of a small ion engine. However, the proposal was refused by ESA. A joint NASA–ESA asteroid mission was then drawn up for a Multiple Asteroid Orbiter with Solar Electric Propulsion (MAOSEP), with one of the mission profiles including an orbit of Vesta. NASA indicated they were not interested in an asteroid mission. Instead, ESA set up a technological study of a spacecraft with an ion drive. Other missions to the asteroid belt were proposed in the 1980s by France, Germany, Italy, and the United States, but none were approved.[94] Exploration of Ceres by fly-by and impacting penetrator was the second main target of the second plan of the multiaimed Soviet Vesta mission, developed in cooperation with European countries for realisation in 1991–1994 but canceled due to the Soviet Union disbanding.

In the early 1990s, NASA initiated the Discovery Program, which was intended to be a series of low-cost scientific missions. In 1996, the program's study team recommended as a high priority a mission to explore the asteroid belt using a spacecraft with an ion engine. Funding for this program remained problematic for several years, but by 2004 the Dawn vehicle had passed its critical design review.[95]

It was launched on 27 September 2007, as the space mission to make the first visits to both Vesta and Ceres. On 3 May 2011, Dawn acquired its first targeting image 1.2 million kilometers from Vesta.[96] After orbiting Vesta for 13 months, Dawn used its ion engine to depart for Ceres, with gravitational capture occurring on 6 March 2015[97] at a separation of 61,000 km,[98] four months prior to the New Horizons flyby of Pluto.

Dawn's mission profile calls for it to study Ceres from a series of circular polar orbits at successively lower altitudes. It will enter its first observational orbit ("RC3") around Ceres at an altitude of 13,500 km on 23 April 2015, staying for only about one orbit (fifteen days).[23][99] The spacecraft will subsequently reduce its orbital distance to 4,400 km for its second observational orbit ("survey") for three weeks,[100] then down to 1,470 km ("HAMO") for two months[101] and then down to its final orbit at 375 km ("LAMO") for at least three months.[102] The spacecraft instrumentation includes a framing camera, a visual and infrared spectrometer, and a gamma-ray and neutron detector. These instruments will examine Ceres's shape and elemental composition.[103] On January 13, 2015, Dawn took the first images of Ceres at near-Hubble resolution, revealing impact craters and a small high-albedo spot on the surface, near the same location as that observed previously. Additional photo sessions, at increasingly better resolution took place on 25 January, 4, 12, 19, and 25 February, 1 March, and 10 and 15 April.[104]

Dawn 's arrival in a stable orbit around Ceres was delayed after, close to reaching Ceres, it was hit by a cosmic ray, making it take another, longer route around Ceres in back, instead of a direct spiral towards it.

The Chinese Space Agency is designing a sample retrieval mission from Ceres that would take place during the 2020s.[105]

Gallery

|

|

-

Color image of Ceres by the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) in 2004

-

Ceres by Dawn

25 January 2015 -

Ceres by Dawn

4 February 2015 -

Ceres by Dawn

19 February 2015 -

Ceres by Dawn

10 April 2015 -

Ceres by Dawn

14 April 2015 -

Ceres by Dawn

26 April 2015

(anaglyph; image2; image3).

Animations

-

Animated Dawn composite of Ceres,

4 February 2015 -

Animated Dawn composite of Ceres,

19 February 2015 -

Animated Dawn composite of Ceres 33,000 km (21,000 mi),

10 April 2015 -

Animated Dawn composite of Ceres 22,000 km (14,000 mi),

14 April 2015

See also

- Ceres in fiction

- Colonization of Ceres

- Former classification of planets

- List of notable asteroids

Notes

- ↑ All other languages but one use a variant of Ceres/Cerere: Russian Tserera, Persian Seres, Japanese Keresu. The exception is Chinese, which uses 'grain-god(dess) star' (穀神星 gǔshénxīng). Note that this is unlike the goddess Ceres, where Chinese does use the Latin name (刻瑞斯 kèruìsī).

- ↑ In 1807 Klaproth tried to change the name to the more etymologically justified "cererium", but it did not catch on.[41]

- ↑ This emission rate is modest compared to those calculated for the tidally driven plumes of Enceladus (a smaller body) and Europa (a larger body), 200 kg/s[72] and 7000 kg/s,[73] respectively.

References

- ↑ Schmadel, Lutz (2003). Dictionary of minor planet names (5th ed.). Germany: Springer. p. 15. ISBN 978-3-540-00238-3.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Simpson, D. P. (1979). Cassell's Latin Dictionary (5th ed.). London: Cassell Ltd. p. 883. ISBN 978-0-304-52257-6.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 "1 Ceres". JPL Small-Body Database Browser. Archived from the original on 4 August 2012. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- ↑ "The MeanPlane (Invariable plane) of the Solar System passing through the barycenter". 3 April 2009. Archived from the original on 14 May 2009. Retrieved 10 April 2009. (produced with Solex 10 written by Aldo Vitagliano; see also Invariable plane)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "AstDyS-2 Ceres Synthetic Proper Orbital Elements". Department of Mathematics, University of Pisa, Italy. Archived from the original on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 1 October 2011.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 6.9 Thomas, P. C.; Parker, J. Wm.; McFadden, L. A. et al. (2005). "Differentiation of the asteroid Ceres as revealed by its shape". Nature 437 (7056): 224–226. Bibcode:2005Natur.437..224T. doi:10.1038/nature03938. PMID 16148926.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 Carry, Benoit et al. (2007). "Near-Infrared Mapping and Physical Properties of the Dwarf-Planet Ceres" (PDF). Astronomy & Astrophysics 478 (1): 235–244. arXiv:0711.1152. Bibcode:2008A&A...478..235C. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078166.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 "Ceres". NASA fact sheet. NASA. 2 April 2014. Retrieved 4 May 2014.

- ↑ Calculated based on the known parameters

- ↑ Chamberlain, Matthew A.; Sykes, Mark V.; Esquerdo, Gilbert A. (2007). "Ceres lightcurve analysis – Period determination". Icarus 188 (2): 451–456. Bibcode:2007Icar..188..451C. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2006.11.025.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 Li, Jian-Yang; McFadden, Lucy A.; Parker, Joel Wm. (2006). "Photometric analysis of 1 Ceres and surface mapping from HST observations". Icarus 182 (1): 143–160. Bibcode:2006Icar..182..143L. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2005.12.012. Retrieved 8 December 2007.

- ↑ Angelo, Joseph A., Jr (2006). Encyclopedia of Space and Astronomy. New York: Infobase. p. 122. ISBN 0-8160-5330-8.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Saint-Pé, O.; Combes, N.; Rigaut F. (1993). "Ceres surface properties by high-resolution imaging from Earth". Icarus 105 (2): 271–281. Bibcode:1993Icar..105..271S. doi:10.1006/icar.1993.1125.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 14.6 Rivkin, A. S.; Volquardsen, E. L.; Clark, B. E. (2006). "The surface composition of Ceres:Discovery of carbonates and iron-rich clays" (PDF). Icarus 185 (2): 563–567. Bibcode:2006Icar..185..563R. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2006.08.022. Retrieved 8 December 2007.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Menzel, Donald H.; and Pasachoff, Jay M. (1983). A Field Guide to the Stars and Planets (2nd ed.). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. p. 391. ISBN 978-0-395-34835-2.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 APmag and AngSize generated with Horizons (Ephemeris: Observer Table: Quantities = 9,13,20,29) Archived 5 October 2011 at WebCite

- ↑ "Ceres". Dictionary.com. Random House, Inc. Archived from the original on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2007.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 18.5 18.6 18.7 18.8 18.9 18.10 McCord, T. B.; Sotin, C. (2005-05-21). "Ceres: Evolution and current state". Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets 110 (E5): E05009. doi:10.1029/2004JE002244. Retrieved 2015-03-07.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 O'Brien, D. P.; Travis, B. J.; Feldman, W. C.; Sykes, M. V.; Schenk, P. M.; Marchi, S.; Russell, C. T.; Raymond, C. A. (March 2015). "The Potential for Volcanism on Ceres due to Crustal Thickening and Pressurization of a Subsurface Ocean" (PDF). 46th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference. p. 2831. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- ↑ NASA Science News: Water Detected on Dwarf Planet Ceres , by Production editor: Dr. Tony Phillips | Credit: Science@NASA (22 January 2014)

- ↑ Landau, Elizabeth; Brown, Dwayne (6 March 2015). "NASA Spacecraft Becomes First to Orbit a Dwarf Planet". NASA. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ↑ "Dawn Spacecraft Begins Approach to Dwarf Planet Ceres". Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Rayman, Marc (6 March 2015). "Dawn Journal: Ceres Orbit Insertion!". Planetary Society. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ↑ O'Neill, I. (25 February 2015). "Ceres' Mystery Bright Dots May Have Volcanic Origin". Discovery Communications. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- ↑ Landau, E. (25 February 2015). "'Bright Spot' on Ceres Has Dimmer Companion". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- ↑ Lakdawalla, E. (26 February 2015). "At last, Ceres is a geological world". Planetary Society. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ↑

- ↑ Atkinson, Nancy (3 March 2015). "Bright Spots on Ceres Likely Ice, Not Cryovolcanoes". Universe Today. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 29.4 29.5 29.6 29.7 29.8 29.9 29.10 Hoskin, Michael (26 June 1992). "Bode's Law and the Discovery of Ceres". Observatorio Astronomico di Palermo "Giuseppe S. Vaiana". Archived from the original on 18 January 2010. Retrieved 5 July 2007.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 Hogg, Helen Sawyer (1948). "The Titius-Bode Law and the Discovery of Ceres". Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada 242: 241–246. Bibcode:1948JRASC..42..241S.

- ↑ Hoskin, Michael (1999). The Cambridge Concise History of Astronomy. Cambridge University press. pp. 160–161. ISBN 978-0-521-57600-0.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 32.4 32.5 32.6 Forbes, Eric G. (1971). "Gauss and the Discovery of Ceres". Journal for the History of Astronomy 2: 195–199. Bibcode:1971JHA.....2..195F.

- ↑ Clifford J. Cunningham (2001). The first asteroid: Ceres, 1801–2001. Star Lab Press. ISBN 978-0-9708162-1-4.

- ↑ Hilton, James L. "Asteroid Masses and Densities" (PDF). U.S. Naval Observatory. Retrieved 23 June 2008.

- ↑ Hughes, D. W. (1994). "The Historical Unravelling of the Diameters of the First Four Asteroids". R.A.S. Quarterly Journal 35 (3): 331. Bibcode:1994QJRAS..35..331H.(Page 335)

- ↑ Foderà Serio, G.; Manara, A.; Sicoli, P. (2002). "Giuseppe Piazzi and the Discovery of Ceres". In W. F. Bottke Jr., A. Cellino, P. Paolicchi, and R. P. Binzel. Asteroids III (PDF). Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona Press. pp. 17–24. Retrieved 25 June 2009.

- ↑ Rüpke, Jörg (2011). A Companion to Roman Religion. John Wiley and Sons. pp. 90–. ISBN 978-1-4443-4131-7.

- ↑ Unicode value U+26B3

- ↑ Gould, B. A. (1852). "On the symbolic notation of the asteroids". Astronomical Journal 2 (34): 80. Bibcode:1852AJ......2...80G. doi:10.1086/100212.

- ↑ "Cerium: historical information". Adaptive Optics. Retrieved 27 April 2007.

- ↑ "Cerium". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005.

- ↑ "Amalgamator Features 2003: 200 Years Ago". 30 October 2003. Archived from the original on 7 February 2006. Retrieved 21 August 2006.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 Hilton, James L. (17 September 2001). "When Did the Asteroids Become Minor Planets?". Archived from the original on 18 January 2010. Retrieved 16 August 2006.

- ↑ Herschel, William (6 May 1802). "Observations on the two lately discovered celestial Bodies.". Archived from the original on 5 October 2011.

- ↑ Battersby, Stephen (16 August 2006). "Planet debate: Proposed new definitions". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2007.

- ↑ Connor, Steve (16 August 2006). "Solar system to welcome three new planets". NZ Herald. Archived from the original on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2007.

- ↑ Gingerich, Owen et al. (16 August 2006). "The IAU draft definition of "Planet" and "Plutons"". IAU. Archived from the original on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2007.

- ↑ "The IAU Draft Definition of Planets And Plutons". SpaceDaily. 16 August 2006. Archived from the original on 18 January 2010. Retrieved 27 April 2007.

- ↑ Geoff Gaherty, "How to Spot Giant Asteroid Vesta in Night Sky This Week", 3 August 2011 How to Spot Giant Asteroid Vesta in Night Sky This Week | Asteroid Vesta Skywatching Tips | Amateur Astronomy, Asteroids & Comets | Space.com Archived 5 October 2011 at WebCite

- ↑ "Question and answers 2". IAU. Archived from the original on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 31 January 2008.

- ↑ Spahr, T. B. (7 September 2006). "MPEC 2006-R19: EDITORIAL NOTICE". Minor Planet Center. Archived from the original on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 31 January 2008.

the numbering of "dwarf planets" does not preclude their having dual designations in possible separate catalogues of such bodies.

- ↑ Lang, Kenneth (2011). The Cambridge Guide to the Solar System. Cambridge University Press. pp. 372, 442.

- ↑ NASA/JPL, Dawn Views Vesta, 2 August 2011 Archived 5 October 2011 at WebCite ("Dawn will orbit two of the largest asteroids in the Main Belt").

- ↑ de Pater; Lissauer (2010). Planetary Sciences (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85371-2.

- ↑ Mann; Nakamura; Mukai (2009). Small bodies in planetary systems. Lecture Notes in Physics 758. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-540-76934-7.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Kovacevic, A.; Kuzmanoski, M. (2007). "A New Determination of the Mass of (1) Ceres". Earth, Moon, and Planets 100 (1–2): 117–123. Bibcode:2007EM&P..100..117K. doi:10.1007/s11038-006-9124-4.

- ↑ Pitjeva, E. V. (2005). "High-Precision Ephemerides of Planets—EPM and Determination of Some Astronomical Constants". Solar System Research 39 (3): 176. Bibcode:2005SoSyR..39..176P. doi:10.1007/s11208-005-0033-2.

- ↑ about forty percent that of Australia, a third the size of the US or Canada, 12× that of the UK

- ↑ 0.72–0.77 anhydrous rock by mass, per William B. McKinnon (2008) "On The Possibility Of Large KBOs Being Injected Into The Outer Asteroid Belt". American Astronomical Society, DPS meeting No. 40, #38.03 Archived 5 October 2011 at WebCite

- ↑ Carey, Bjorn (7 September 2005). "Largest Asteroid Might Contain More Fresh Water than Earth". SPACE.com. Archived from the original on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 16 August 2006.

- ↑ Zolotov, M. Yu. (2009). "On the Composition and Differentiation of Ceres". Icarus 204 (1): 183–193. Bibcode:2009Icar..204..183Z. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2009.06.011.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 62.2 Parker, J. W.; Stern, Alan S.; Thomas Peter C. et al. (2002). "Analysis of the first disk-resolved images of Ceres from ultraviolet observations with the Hubble Space Telescope". The Astrophysical Journal 123 (1): 549–557. arXiv:astro-ph/0110258. Bibcode:2002AJ....123..549P. doi:10.1086/338093.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 63.2 "Keck Adaptive Optics Images the Dwarf Planet Ceres". Adaptive Optics. 11 October 2006. Archived from the original on 18 January 2010. Retrieved 27 April 2007.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 "Largest Asteroid May Be 'Mini Planet' with Water Ice". HubbleSite. 7 September 2005. Archived from the original on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 16 August 2006.

- ↑

- ↑ LPSC 2015: First results from Dawn at Ceres: provisional place names and possible plumes

- ↑ Rayman, Marc (April 8, 2015). Now Appearing At a Dwarf Planet Near You: NASA's Dawn Mission to the Asteroid Belt (Speech). Silicon Valley Astronomy Lectures. Foothill College, Los Altos, CA.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 A'Hearn, Michael F.; Feldman, Paul D. (1992). "Water vaporization on Ceres". Icarus 98 (1): 54–60. Bibcode:1992Icar...98...54A. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(92)90206-M.

- ↑ Jewitt, D; Chizmadia, L.; Grimm, R.; Prialnik, D (2007). "Water in the Small Bodies of the Solar System". In Reipurth, B.; Jewitt, D.; Keil, K. Protostars and Planets V (PDF). University of Arizona Press. pp. 863–878. ISBN 0-8165-2654-0.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 70.2 70.3 Küppers, M.; O'Rourke, L.; Bockelée-Morvan, D.; Zakharov, V.; Lee, S.; Von Allmen, P.; Carry, B.; Teyssier, D.; Marston, A.; Müller, T.; Crovisier, J.; Barucci, M. A.; Moreno, R. (23 January 2014). "Localized sources of water vapour on the dwarf planet (1) Ceres". Nature 505 (7484): 525–527. Bibcode:2014Natur.505..525K. doi:10.1038/nature12918. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 24451541.

- ↑ Campins, H.; Comfort, C. M. (2014-01-23). "Solar system: Evaporating asteroid". Nature 505 (7484): 487–488. doi:10.1038/505487a. PMID 24451536.

- ↑ Hansen, C. J.; Esposito, L.; Stewart, A. I.; Colwell, J.; Hendrix, A.; Pryor, W.; Shemansky, D.; West, R. (2006-03-10). "Enceladus' Water Vapor Plume". Science 311 (5766): 1422–1425. doi:10.1126/science.1121254. PMID 16527971.

- ↑ Roth, L.; Saur, J.; Retherford, K. D.; Strobel, D. F.; Feldman, P. D.; McGrath, M. A.; Nimmo, F. (26 November 2013). "Transient Water Vapor at Europa's South Pole" (PDF). Science 343 (6167): 171–174. doi:10.1126/science.1247051. PMID 24336567. Retrieved 2014-01-26.

- ↑ O'Neill, Ian (5 March 2009). "Life on Ceres: Could the Dwarf Planet be the Root of Panspermia". Universe Today. Retrieved 30 January 2012.

- ↑ Catling, David C. (2013). Astrobiology: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 99. ISBN 0-19-958645-4.

- ↑ Boyle, Alan (22 January 2014). "Is There Life on Ceres? Dwarf Planet Spews Water Vapor". NBC. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- ↑ "Glaciopanspermia: Seeding the Terrestrial Planets with Life?" Joop M. Houtkooper, Institute for Psychobiology and Behavioral Medicine, Justus-Liebig-University, Giessen, Germany

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 Cellino, A. et al. (2002). "Spectroscopic Properties of Asteroid Families". Asteroids III (PDF). University of Arizona Press. pp. 633–643 (Table on p. 636). Bibcode:2002aste.conf..633C.

- ↑ Kelley, M. S.; Gaffey, M. J. (1996). "A Genetic Study of the Ceres (Williams #67) Asteroid Family". Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society 28: 1097. Bibcode:1996BAAS...28R1097K.

- ↑ Williams, David R. (2004). "Asteroid Fact Sheet". Archived from the original on 18 January 2010.

- ↑ Kovačević, A. B. (2011). "Determination of the mass of Ceres based on the most gravitationally efficient close encounters". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 419 (3): 2725–2736. arXiv:1109.6455. Bibcode:2012MNRAS.419.2725K. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2011.19919.x.

- ↑ Christou, A. A. (2000). "Co-orbital objects in the main asteroid belt". Astronomy and Astrophysics 356: L71–L74. Bibcode:2000A&A...356L..71C.

- ↑ Christou, A. A.; Wiegert, P. (January 2012). "A population of Main Belt Asteroids co-orbiting with Ceres and Vesta". Icarus 217 (1): 27–42. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2011.10.016. ISSN 0019-1035.

- ↑ "Solex numbers generated by Solex". Archived from the original on 29 April 2009. Retrieved 3 March 2009.

- ↑ Petit, Jean-Marc; Morbidelli, Alessandro (2001). "The Primordial Excitation and Clearing of the Asteroid Belt" (PDF). Icarus 153 (2): 338–347. Bibcode:2001Icar..153..338P. doi:10.1006/icar.2001.6702. Retrieved 25 June 2009.

- ↑ About a 10% chance of the asteroid belt acquiring a Ceres-mass KBO. William B. McKinnon, 2008, "On The Possibility Of Large KBOs Being Injected Into The Outer Asteroid Belt". American Astronomical Society, DPS meeting No. 40, #38.03 Archived 5 October 2011 at WebCite

- ↑ Thomas, Peter C.; Binzel, Richard P.; Gaffey, Michael J. et al. (1997). "Impact Excavation on Asteroid 4 Vesta: Hubble Space Telescope Results". Science 277 (5331): 1492–1495. Bibcode:1997Sci...277.1492T. doi:10.1126/science.277.5331.1492.

- ↑ 88.0 88.1 Castillo-Rogez, J. C.; McCord, T. B.; and Davis, A. G. (2007). "Ceres: evolution and present state" (PDF). Lunar and Planetary Science. XXXVIII: 2006–2007. Retrieved 25 June 2009.

- ↑ Martinez, Patrick, The Observer's Guide to Astronomy, page 298. Published 1994 by Cambridge University Press

- ↑ Millis, L. R.; Wasserman, L. H.; Franz, O. Z. et al. (1987). "The size, shape, density, and albedo of Ceres from its occultation of BD+8°471". Icarus 72 (3): 507–518. Bibcode:1987Icar...72..507M. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(87)90048-0.

- ↑ "Observations reveal curiosities on the surface of asteroid Ceres". Archived from the original on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 16 August 2006.

- ↑ 92.0 92.1 "Asteroid Occultation Updates". Asteroidoccultation.com. 22 December 2012. Archived from the original on 2012-07-12. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- ↑ "Water Detected on Dwarf Planet Ceres". Science.nasa.gov. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ↑ Ulivi, Paolo; Harland, David (2008). Robotic Exploration of the Solar System: Hiatus and Renewal, 1983–1996. Springer Praxis Books in Space Exploration. Springer. pp. 117–125. ISBN 0-387-78904-9.

- ↑ Russell, C. T.; Capaccioni, F.; Coradini, A. et al. (October 2007). "Dawn Mission to Vesta and Ceres" (PDF). Earth, Moon, and Planets 101 (1–2): 65–91. Bibcode:2007EM&P..101...65R. doi:10.1007/s11038-007-9151-9. Retrieved 13 June 2011.

- ↑ Cook, Jia-Rui C.; Brown, Dwayne C. (11 May 2011). "NASA's Dawn Captures First Image of Nearing Asteroid". NASA/JPL. Retrieved 14 May 2011.

- ↑ Schenk, P. (15 January 2015). "Year of the 'Dwarves': Ceres and Pluto Get Their Due". Planetary Society. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- ↑ Rayman, Marc (1 December 2014). "Dawn Journal: Looking Ahead at Ceres". Planetary Society. Retrieved 2015-03-02.

- ↑ Rayman, Marc (3 March 2014). "Dawn Journal: Maneuvering Around Ceres". Planetary Society. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ↑ Rayman, Marc (30 April 2014). "Dawn Journal: Explaining Orbit Insertion". Planetary Society. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ↑ Rayman, Marc (30 June 2014). "Dawn Journal: HAMO at Ceres". Planetary Society. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ↑ Rayman, Marc (31 August 2014). "Dawn Journal: From HAMO to LAMO and Beyond". Planetary Society. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ↑ Russel, C. T.; Capaccioni, F.; Coradini, A. et al. (2006). "Dawn Discovery mission to Vesta and Ceres: Present status". Advances in Space Research 38 (9): 2043–2048. Bibcode:2006AdSpR..38.2043R. doi:10.1016/j.asr.2004.12.041.

- ↑ Rayman, Marc (30 January 2015). "Dawn Journal: Closing in on Ceres". Planetary Society. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- ↑ China's Deep-space Exploration to 2030 by Zou Yongliao Li Wei Ouyang Ziyuan Key Laboratory of Lunar and Deep Space Exploration, National Astronomical Observatories, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing

- ↑ Krummheuer, B. (25 February 2015). "Dawn: Two new glimpses of dwarf planet Ceres". Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ↑ Rayman, Marc (25 February 2015). "Dawn Journal: Ceres' Deepening Mysteries". Planetary Society. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ceres (dwarf planet). |

- Dawn mission home page at JPL

- A simulation of the orbit of Ceres

- JPL Ephemeris

- How Gauss determined the orbit of Ceres from keplersdiscovery.com

- Hilton, James L. (1999). "U.S. Naval Observatory Ephemerides of the Largest Asteroids". The Astronomical Journal 117 (2): 1077. Bibcode:1999AJ....117.1077H. doi:10.1086/300728.

- Map of Ceres based on Dawn's 19 February 2015 images (NASA/JPL/UCLA/MPS/DLR/IDA/"Gerald"/Phil Stooke) – from forum post by Phil Stooke

- Northern and southern hemisphere maps – polar azimuthal projections (NASA/JPL/UCLA/MPS/DLR/IDA/"Gerald"/Phil Stooke) – from forum posts by Phil Stooke

- Animated reprojected colorized map of Ceres (NASA/JPL-Caltech/UCLA/MPS/DLR/IDA/HST/Phil Stooke/"Gerald") uploaded 22 February 2015 (larger version here)

- Colorized map of Ceres(NASA/JPL-Caltech/UCLA/MPS/DLR/IDA/HST/"Gerald"/Phil Stooke/"Herobrine") from forum post by "Herobrine"

- Animated Ceres map (NASA/JPL-Caltech/UCLA/MPS/DLR/IDA/"Gerald") showing changes as a function of solar time, from forum post by "Gerald"

- Pairs of Ceres images for cross-eyed stereo, from forum post by "algorimancer"

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||