Centrifuge

A centrifuge is a piece of equipment that puts an object in rotation around a fixed axis (spins it in a circle), applying a potentially strong force perpendicular to the axis of spin (outward). The centrifuge works using the sedimentation principle, where the centripetal acceleration causes denser substances and particles to move outward in the radial direction. At the same time, objects that are less dense are displaced and move to the center. In a laboratory centrifuge that uses sample tubes, the radial acceleration causes denser particles to settle to the bottom of the tube, while low-density substances rise to the top.[1]

There are many types of centrifuge designed for different applications. Industrial scale centrifuges are commonly used in manufacturing and waste processing to sediment suspended solids, or to separate immiscible liquids. An example is the cream separator found in dairies. Very high speed centrifuges and ultracentrifuges able to provide very high accelerations can separate fine particles down to the nano-scale, and molecules of different masses.

Large centrifuges are used to simulate high gravity or acceleration environments (for example, high-G training for test pilots). Medium-sized centrifuges are used in washing machines and at some swimming pools to wring water out of fabrics.

Gas centrifuges are used for isotope separation, such as to enrich nuclear fuel for fissile isotopes.

History and predecessors

English military engineer Benjamin Robins (1707–1751) invented a whirling arm apparatus to determine drag. In 1864, Antonin Prandtl proposed the idea of a dairy centrifuge to separate cream from milk. The idea was subsequently put into practice by his brother, Alexander Prandtl, who made improvements to his brother's design, and exhibited a working butterfat extraction machine in 1875.[2]

Types

There are multiple types of centrifuge, which can be classified by intended use or by rotor design:

Types by rotor design: [3][4][5][6]

- Fixed-angle centrifuges are designed to hold the sample containers at a constant angle relative to the central axis.

- Swinging head (or swinging bucket) centrifuges, in contrast to fixed-angle centrifuges, have a hinge where the sample containers are attached to the central rotor. This allows all of the samples to swing outwards as the centrifuge is spun.

- Continuous tubular centrifuges do not have individual sample vessels and are used for high volume applications.

Types by intended use:

- Laboratory centrifuges, are general-purpose instruments of several types with distinct, but overlapping, capabilities. These include clinical centrifuges, superspeed centrifuges and preparative ultracentrifuges.

- Analytical ultracentrifuges are designed to perform sedimentation analysis of macromolecules using the principles devised by Theodor Svedberg.

- Haematocrit centrifuges are used to measure the volume percentage of red blood cells in whole blood.

- Gas centrifuges, including Zippe-type centrifuges, for isotopic separations in the gas phase.

Industrial centrifuges may otherwise be classified according to the type of separation of the high density fraction from the low density one:

- Screen centrifuges, where the centrifugal acceleration allows the liquid to pass through a screen of some sort, through which the solids cannot go (due to granulometry larger than the screen gap or due to agglomeration). Common types are:

- Screen/scroll centrifuges

- Pusher centrifuges

- Peeler centrifuges

- Decanter centrifuges, in which there is no physical separation between the solid and liquid phase, rather an accelerated settling due to centrifugal acceleration.

- Continuous liquid; common types are:

Uses

Laboratory separations

A wide variety of laboratory-scale centrifuges are used in chemistry, biology, biochemistry and clinical medicine for isolating and separating suspensions and immiscible liquids. They vary widely in speed, capacity, temperature control, and other characteristics. Laboratory centrifuges often can accept an range of different fixed-angle and swinging bucket rotors able to carry different numbers of centrifuge tubes and rated for specific maximum speeds. Controls vary from simple electrical timers to programmable models able to control acceleration and deceleration rates, running speeds, and temperature regimes. Ultracentrifuges spin the rotors under vacuum, eliminating air resistance and enabling exact temperature control. Zonal rotors and continuous flow systems are capable of handing bulk and larger sample volumes, respectively, in a laboratory-scale instrument.[1]

Isotope separation

Other centrifuges, the first being the Zippe-type centrifuge, separate isotopes, and these kinds of centrifuges are in use in nuclear power and nuclear weapon programs.

Gas centrifuges are used in uranium enrichment. The heavier isotope of uranium (uranium-238) in the uranium hexafluoride gas tends to concentrate at the walls of the centrifuge as it spins, while the desired uranium-235 isotope is extracted and concentrated with a scoop selectively placed inside the centrifuge. It takes many thousands of centrifugations to enrich uranium enough for use in a nuclear reactor (around 3.5% enrichment), and many thousands more to enrich it to weapons-grade (above 90% enrichment) for use in nuclear weapons.

Aeronautics and astronautics

Human centrifuges are exceptionally large centrifuges that test the reactions and tolerance of pilots and astronauts to acceleration above those experienced in the Earth's gravity.

The US Air Force at Holloman Air Force Base, New Mexico operates a human centrifuge. The centrifuge at Holloman AFB is operated by the aerospace physiology department for the purpose of training and evaluating prospective fighter pilots for high-g flight in Air Force fighter aircraft.[7]

The use of large centrifuges to simulate a feeling of gravity has been proposed for future long-duration space missions. Exposure to this simulated gravity would prevent or reduce the bone decalcification and muscle atrophy that affect individuals exposed to long periods of freefall. [7] [8]

The first centrifuges used for human research were used by Erasmus Darwin, the grandfather of Charles Darwin. The first largescale human centrifuge designed for Aeronautical training was created in Germany in 1933.[9]

Geotechnical centrifuge modeling

Geotechnical centrifuge modeling is used for physical testing of models involving soils. Centrifuge acceleration is applied to scale models to scale the gravitational acceleration and enable prototype scale stresses to be obtained in scale models. Problems such as building and bridge foundations, earth dams, tunnels, and slope stability, including effects such as blast loading and earthquake shaking.[10]

Commercial applications

- Centrifuges with a batch weight of up to 2,200 kg per charge are used in the sugar industry to separate the sugar crystals from the mother liquor.[11]

- Standalone centrifuges for drying (hand-washed) clothes – usually with a water outlet.

- Washing machines

- Centrifuges are used in the attraction Mission: SPACE, located at Epcot in Walt Disney World, which propels riders using a combination of a centrifuge and a motion simulator to simulate the feeling of going into space.

- In soil mechanics, centrifuges utilize centrifugal acceleration to match soil stresses in a scale model to those found in reality.

- Large industrial centrifuges are commonly used in water and wastewater treatment to dry sludges. The resulting dry product is often termed cake, and the water leaving a centrifuge after most of the solids have been removed is called centrate.

- Large industrial centrifuges are also used in the oil industry to remove solids from the drilling fluid.

- Disc-stack centrifuges used by some companies in the oil sands industry to separate small amounts of water and solids from bitumen

- Centrifuges are used to separate cream (remove fat) from milk; see Separator (milk).

Mathematical description

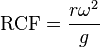

Protocols for centrifugation typically specify the amount of acceleration to be applied to the sample, rather than specifying a rotational speed such as revolutions per minute. This distinction is important because two rotors with different diameters running at the same rotational speed will subject samples to different accelerations. During circular motion the acceleration is the product of the radius and the square of the angular velocity  , and the acceleration relative to "g" is traditionally named "relative centrifugal force" (RCF). The acceleration is measured in multiples of "g" (or × "g"), the standard acceleration due to gravity at the Earth's surface, a dimensionless quantity given by the expression:

, and the acceleration relative to "g" is traditionally named "relative centrifugal force" (RCF). The acceleration is measured in multiples of "g" (or × "g"), the standard acceleration due to gravity at the Earth's surface, a dimensionless quantity given by the expression:

where

is earth's gravitational acceleration,

is earth's gravitational acceleration, is the rotational radius,

is the rotational radius, is the angular velocity in radians per unit time

is the angular velocity in radians per unit time

This relationship may be written as

where

is the rotational radius measured in millimeters (mm), and

is the rotational radius measured in millimeters (mm), and is rotational speed measured in revolutions per minute (RPM).

is rotational speed measured in revolutions per minute (RPM).

To avoid having to perform a mathematical calculation every time, one can find nomograms for converting RCF to rpm for a rotor of a given radius. A ruler or other straight edge lined up with the radius on one scale, and the desired RCF on another scale, will point at the correct rpm on the third scale.[12] Based on automatic rotor recognition, modern centrifuges have a button for automatic conversion from RCF to rpm and vice versa.

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Susan R. Mikkelsen & Eduardo Cortón. Bioanalytical Chemistry, Ch. 13. Centrifugation Methods. John Wiley & Sons, Mar 4, 2004, pp. 247-267.

- ↑ Vogel-Prandtl,Johanna Ludwig Prandtl: A Biographical Sketch, Remembrances and Documents, English trans. V. Vasanta Ram. The International Centre for Theoretical Physics Trieste, Italy, pub. August 14, 2004. pp. 10-11.

- ↑ "Basics of Centrifugation". Cole-Parmer. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- ↑ "Plasmid DNA Separation: Fixed-Angle and Vertical Rotors in the Thermo Scientific Sorvall Discovery™ M120 & M150 Microultracentrifuges" (Thermo Fischer publication)

- ↑ http://uqu.edu.sa/files2/tiny_mce/plugins/filemanager/files/4250119/lectures/1._instr.pdf

- ↑ Heidcamp, Dr. William H. "Appendix F". Cell Biology Laboratory Manual. Gustavus Adolphus College,. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "The Pull of HyperGravity - A NASA researcher is studying the strange effects of artificial gravity on humans.". NASA. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- ↑ Hsu, Jeremy. "New Artificial Gravity Tests in Space Could Help Astronauts". Space.com. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- ↑ http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a236267.pdf

- ↑ C. W. W. Ng, Y. H. Wang, L. M. Zhang (2006). Physical Modelling in Geotechnics: proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Physical Modelling in Geotechnics. Taylor & Francis. p. 135. ISBN 0-415-41586-1.

- ↑ article on centrifugal controls, retrieved on June 5, 2010

- ↑ Nomogram example

Further reading

See also

- Lamm equation

- Sedimentation

- Centrifugal force

- Centrifugation

- Sedimentation coefficient

- Clearing factor

- Hydroextractor

- Honey extractor

- Separation process (includes list of techniques)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Centrifuges. |

| Look up centrifuge in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- RCF Calculator and Nomograph

- Centrifugation Rotor Calculator

- Selection of historical centrifuges in the Virtual Laboratory of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science