Centre Party (Finland)

| Centre Party | |

|---|---|

.png) | |

| Finnish name | Suomen Keskusta |

| Swedish name | Centern i Finland |

| Leader | Juha Sipilä |

| Founded | 1906 |

| Headquarters |

Apollonkatu 11 A 00100 Helsinki |

| Student wing | Finnish Centre Students |

| Youth wing | Finnish Centre Youth |

| Membership (2011) | 163,000[1] |

| Ideology |

Nordic agrarianism Liberalism |

| Political position | Centre[2] |

| International affiliation | Liberal International |

| European affiliation | Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe |

| European Parliament group | Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe |

| Colours | Green |

| Parliament |

49 / 200 |

| European Parliament |

3 / 13 |

| Municipalities |

3,077 / 9,674 |

| Website | |

|

www | |

|

Politics of Finland Political parties Elections | |

The Centre Party of Finland (Finnish: Suomen Keskusta, Kesk; Swedish: Centern i Finland) is a centrist,[3] agrarian,[3][4][5][6] and liberal[4][5][7] political party in Finland. It is one of the four largest political parties in the country, along with the National Coalition Party, the Social Democratic Party and The Finns Party, and currently has 35 seats in the Finnish Parliament. The Centre Party chairman is Juha Sipilä, who was elected in June 2012 to follow Mari Kiviniemi, the ex-Prime Minister of Finland.

Founded in 1906 as the Agrarian League, the party represented rural communities and supported decentralisation of political power from Helsinki. In the 1920s, the party emerged as the main rivals to the Social Democratic Party, and the party's first Prime Minister, Kyösti Kallio, held the office four times between 1922 and 1937. After World War II, the party settled as one of the four major political parties in Finland. Urho Kekkonen served as President of Finland from 1956 to 1982: by far the longest period of any President. The name 'Centre Party' was adopted in 1965, and 'Centre of Finland' in 1988. The Centre Party was the largest party in Parliament from 2003 to 2011, during which time Matti Vanhanen was Prime Minister for seven years. Following the 2011 election, the party was reduced in parliamentary representation from the largest party to the fourth largest.

The Centre Party's political influence is greatest in small and rural municipalities, where it often holds a majority of the seats in the municipal councils. Decentralisation is the policy that is most characteristic of the Centre Party. The Centre has been the ruling party in Finland a number of times since Finnish independence. 12 of the Prime Ministers of Finland, three of the Presidents and a former European Commissioner for Economic and Financial Affairs have been from the party. The Finnish Centre Party is the mother organisation of Finnish Centre Youth, Finnish Centre Students, and Finnish Centre Women.

History

Founding of the party

The party was founded in 1906 as a movement of citizens in the Finnish countryside. Before Finnish independence, political power in Finland was centralised in the capital and to the estates of the realm. The centralisation gave space for a new political movement. In 1906 two agrarian movements were founded. They merged in 1908 to become one political party known as the Agrarian League or Maalaisliitto. An older, related movement was the temperance movement, which had overlapping membership and which gave future Agrarian League activists experience in working in an organisation.[8]

Santeri Alkio's ideology

Soon the ideas of humanity, education, the spirit of the land, peasant-like freedom, decentralisation, "the issue of poor people", progressivism,[9] and later the "green wave" became the main political phrases used to describe the ideology of the party. Santeri Alkio was the most important ideological father of the party.

Defending the republic against monarchists

At the dawn of Finnish independence conservative social forces made an attempt to establish the Kingdom of Finland. The Agrarian League opposed monarchism fiercely[9] even though monarchists claimed that a new king from the German Empire and Hohenzollern would have safeguarded Finnish foreign relations. At this time, anti-anarchist peasants threatened the existence of the party.[10][11]

Because around 40 Social Democratic members of the Parliament had escaped to Russia after the Finnish Civil War and about 50 others had been arrested, the Agrarian League members of the Parliament became the only republicans in Parliament in 1918. Nevertheless, the news about the problems of the German Empire from German liberals encouraged the fight of Agrarian League in the Parliament.[12]

The Agrarian League managed to maintain the republican voices in the Parliament until the fall of the German Empire, which ruined the dreams of the monarchists.[13]

The relentless opposition to the monarchy was rewarded in the parliamentary election 1919 and the party became the biggest non-socialist party in Finland with 19.7% of the votes.

Moderate force in post-war Finland

After the 1919 election, the centrist and progressive forces, including the Agrarian League, were constant members in Finnish governments. Their moderate attitude in restless post-war Finland secured a steady growth in following elections. The Party formed many centrist minority governments with National Progressive Party and got its first Prime Ministers Kyösti Kallio 1922 and Juho Sunila 1927.

Conciliatory power between the extreme right and left

For the Agrarian League, the centrist governments were just a transitional period towards an era, which would integrate the "red" and "white" sides of the Civil War into one nation. Nevertheless, not everyone were happy with the conciliatory politics of centrist governments. The extreme right Lapua Movement grew bigger and bigger in the Agrarian League strongholds in the countryside. Many party members joined the new radical movement. The Lapua Movement organised assaults and kidnappings in Finland between 1929 and 1932. In 1930, after the kidnapping of progressive president Kaarlo Juho Ståhlberg, the Agrarian League broke off all its ties to the movement and got a new political enemy in the countryside - The Patriotic People's Movement (IKL), which was founded after the Lapua Movement was outlawed.[14]

In the parliamentary election 1933 the main campaign issues were the differing attitudes towards democracy and the rule of law between the Patriotic Electoral Alliance (National Coalition Party and Patriotic People's Movement) and the Legality Front (Social Democrats, Agrarian League, Swedish People's Party and Progressives). The Patriotic Electoral Alliance favoured continuing the search for suspected Communists - the Communist Party and its affiliated organizations in the spirit of the Lapua Movement. The Legality Front did not want to spend any significant time on searching suspected Communists, but rather wanted to concentrate on keeping the far-right in check. The Legality Front won the elections, but the Agrarian League lost a part of its support.[15][16]

Cooperation with the Social Democrats before World War II

Because of fierce opposition of the President Pehr Evind Svinhufvud the Social Democrats remained outside the government and the Agrarian League was part of the centre-right governments until 1937. In 1937 Presidential election the Agrarian League candidate Kyösti Kallio was elected president with the votes of centrist (Agrarian and Progressive) and social-democratic coalition which wanted to ensure that President Svinhufvud would not be re-elected. The new president allowed the first centre-left government to be formed in Finland. A new era had begun.

World War II

With the outbreak of the Winter War a government of national unity was formed. President Kallio died shortly after the war.

Kekkonen, the centrist statesman

In 1956, Urho Kekkonen, the candidate of the Agrarian League, was elected President of Finland, after serving as Prime Minister several times. Kekkonen remained President until 1982. Kekkonen continued the “active neutrality” policy of his predecessor President Juho Kusti Paasikivi, a doctrine which came to be known as the “Paasikivi–Kekkonen line”. Under it, Finland retained its independence while being able to trade with both NATO members and those of the Warsaw Pact.

Pressure of populism

Veikko Vennamo, a vocal Agrarian politician, ran into serious disagreement particularly with Arvo Korsimo, then Party Secretary of the Agrarian Union, and was excluded from the parliamentary group. As a result, Vennamo immediately started building his own organization and founded a new party, the Finnish Rural Party (Suomen maaseudun puolue, SMP) in 1959. Vennamo was a populist and became a critic of Kekkonen and political corruption within the "old parties", particularly the Centre Party. Although this party had minor successes, it was essentially tied to Veikko Vennamo's person. His son Pekka Vennamo was able to raise the party to new success in 1983, but after this the Rural Party's support declined steadily and eventually the party went bankrupt in 1995. However, immediately after this, the right-wing populist party True Finns (Perussuomalaiset) was founded by former members of SMP.

From Agrarian League to Centre Party

In 1965, the party changed its name to "Centre Party" or Keskustapuolue and in 1988 took its current name Suomen Keskusta (literally Centre of Finland). Despite urbanisation of Finland and a temporary nadir in support, the party managed to continue to attract voters.

The Liberal People's Party (LKP) became a 'member party' of the Centre Party in 1982. The two separated again after the success of the Liberal People's Party in Sweden in 1985.[17]

EU membership - a divisive issue within the party

The Centre Party was a key player in making the decision to apply for Finnish EU membership in 1992. As the leading governing party its support for the application was crucial. The party itself, both leadership and supporters, was far from united on the issue. In the parliament 22 out of 55 Centre MPs voted against the application. In June 1994 the party congress decided to support EU membership (by 1607 votes to 834), but only after the Prime Minister and party chairman Esko Aho threatened to resign if the party were to oppose the membership.

The centrist tradition of defending equal political and economic rights for peripheral areas was reflected in the internal resistance that opposed chairman Aho's ambitions to lead Finland to the EU.[18] The Centre Party was in opposition 1995—2003 and opposed adopting the euro as Finland's currency. However, after regaining power in 2003, the party accepted the euro.

Recent developments

The party congress in June 2012 elected the newcomer Juha Sipilä to replace Mari Kiviniemi as the party's chair. Sipilä defeated young deputy chairman Tuomo Puumala and a well known veteran politician Paavo Väyrynen in the voting.

The previous chairman, Mari Kiviniemi, succeeded Matti Vanhanen as Prime Minister in 2010, serving in the office for one year. At the time she was the third Centre Party Prime Minister of Finland in succession. Anneli Jäätteenmäki preceded Vanhanen and she was the first woman as a Prime Minister of Finland. She did not seek another term as party chair.

Olli Rehn, a member of the party, served in the European Commission for ten years between 2004 and 2014, and was the European Commissioner for Economic and Financial Affairs in 2010–2014.

The Centre Party was the biggest loser of the 2011 parliamentary election, losing 16 seats and going from largest party to fourth place. The party's support was lower than in any parliamentary election since 1917.

Stance

The ideology of the party is unusual in the European context. Unlike many other large parties in Europe its ideology is not primarily based on economic systems. Rather the ideas of humanity, education, the spirit of the land, peasant-like freedom, decentralization, "the issue of poor people", environmentalism and progressivism play a key role in Centrist politician speeches and writings.[9] From the very beginning of its presence, the party has supported the idea of decentralisation.[9]

Despite belonging to the Liberal International, the Centre Party does not play quite the same role in Finnish politics as do liberal parties in other countries, because the party evolved from agrarian roots. The party has a more conservative wing, and prominent conservatives within the party, such as Paavo Väyrynen, have criticised overt economic and social liberalism.[19] In addition, in 2010 the party congress voted to oppose same-sex marriage.[20] When the Finnish Parliament voted on same-sex marriage in 2014, 30 of the 36 Centre MPs voted against it.[21]

The party is also divided on the issue of deepening European integration,[22] and contains a notable eurosceptic faction based on its more rural interests. The party expressly rejects a federal Europe. The party was originally opposed to Finland's membership in the Euro currency, but later stated that it would not seek to withdraw from the Economic and Monetary Union once Finland had entered.

In Finland, there is no large party that supports liberalism per se. Instead, liberalism is found in most major parties including the Centre Party, which supports decentralisation, free will, free and fair trade, and small enterprise. The Centre Party characteristically supports decentralisation, particularly decreasing the central power, increasing the power of municipalities and populating the country evenly. During the party's premierships 2003—2011 these policies were also manifested as transferrals of certain government agencies from the capital to smaller cities in the regions.

Throughout the period of Finland's independence the Centre Party has been the party most often represented in the government. The country's longest-serving president, Urho Kekkonen, was a member of the party, as were two other presidents.

Today, only a small portion of the votes given to the party come from farmers and the Centre Party draws support from a wide range of professions. However, even today rural Finland and small towns form the strongest base of support for the party, although it has strived for a breakthrough in the major southern cities as well. In the 2011 parliamentary election the party received only 4.5 per cent of votes cast in the capital Helsinki, compared to 33.4 per cent in the largely rural electoral district of Oulu.[23]

Organisation

Party structure

In the organisation of the Centre Party, local associations dominate the election of party leaders, the selection of local candidates and drafting of policy. The Headquarters in Apollonkatu, Helsinki leads financing and organisation of elections.

The party has 2.500 local associations,[24] which have 160.000 individual members.[25] The local associations elect their representatives to the Party Congress, which elects the party leadership and decide on policy. The local associations form also 21 regional organisations, which have also their representatives in the Party Congress.

The Party Congress is the highest decision making body of the party. It elects the Chairman, three Deputy Chairmen, the Secretary General and the Party Council.

The Party Council with 135 members is the main decision making body between the Party Congresses. The Party Council elects the Party Government (excluding the leaders elected by the Party Congress) and the Working Committee. The Party Council, the Party Government and the Working Committee must have at least 40% representation of both sexes.

The Finnish Centre Youth, Finnish Centre Students and Finnish Centre Women have their own local and regional organisations, which also name their representatives to the Party Congress.

People

-

Juha Sipilä, Chairman of the Centre Party

-

Annika Saarikko, Deputy Chairman

-

Riikka Manner, Deputy Chairman

-

Juha Rehula, Deputy Chairman

-

Kimmo Tiilikainen, Chairman of the Parliamentary Group

-

Anne Kalmari, Deputy Chairman of the Parliamentary Group

-

Tuomo Puumala, Deputy Chairman of the Parliamentary Group

Chairman

- Juha Sipilä, (Born in Veteli 25 April 1961)

Deputy Chairmen

- Annika Saarikko, (Born in Oripää 10 November 1983), Member of Parliament

- Riikka Manner, (Born in Varkaus 24 August 1981), Member of European Parliament

- Juha Rehula (Born in Hollola 3 June 1963), Member of Parliament

Party Secretary

- Timo Laaninen, (Born in Kaustinen 1 July 1954)

Chairman of the Parliamentary Group

- Kimmo Tiilikainen, (Born in Ruokolahti 17 August 1966)

Deputy Chairmen of the Parliamentary Group

- Anne Kalmari, (Born in Kivijärvi 20 April 1968)

- Tuomo Puumala, (Born in Kaustinen 3 April 1982)

Other famous Centrist politicians today

-

.jpg)

Olli Rehn, European Commissioner for Economic and Financial Affairs

-

Simo Rundgren, Member of Finnish Parliament

-

Janne Seurujärvi, First Sami in the Finnish Parliament

-

Laura Kolbe, Member of Helsinki City Council

-

Timo Kalli, Member of Finnish Parliament, ex-Speaker of Finnish Parliament

-

Sirkka-Liisa Anttila, Member of Finnish Parliament, ex-Minister of Agriculture and Forestry

-

Esko Kiviranta, Member of Finnish Parliament

-

Abdirahim Hussein Mohamed, Vice Chairman of Helsinki Centre

-

Anneli Jäätteenmäki, Member of European Parliament, ex-Prime Minister

-

Mikko Alatalo, Member of Finnish Parliament

-

.jpg)

Lasse Hautala, Member of Finnish Parliament

-

Antti Kaikkonen, Member of Finnish Parliament

-

Seppo Kääriäinen, Member of Finnish Parliament, ex-Minister (many ministerial positions), ex-Speaker of Finnish Parliament

-

Mauri Pekkarinen, Member of Finnish Parliament, ex-Minister (many ministerial positions)

-

Paavo Väyrynen, Three-time presidential candidate, honorary Chairman, ex-Minister (many ministerial positions)

International organisations

The party is a member of the Liberal International and the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe Party and subscribes to the liberal manifestos of these organisations. Its members in the European Parliament are members of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe Group. The Centre Party has been a full member of the Liberal International since 1988, having first joined as an observer member in 1983.[26]

Prominent party leaders

-

Santeri Alkio, political ideologist

-

Lauri Kristian Relander, President 1925-1931

-

Kyösti Kallio, Prime Minister four times 1922-1937, President 1937-1940

-

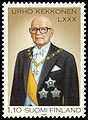

Urho Kekkonen, Prime Minister twice 1950-1956, President 1956-1981

-

Ahti Karjalainen, Prime Minister twice 1962-1963 and 1970–1971

-

Johannes Virolainen, Prime Minister 1964-1966

-

Esko Aho, Prime Minister 1991-1995, Executive Vice President of Nokia

-

Anneli Jäätteenmäki, first female Prime Minister 2003

-

Matti Vanhanen, Prime Minister 2003-2010

-

Mari Kiviniemi, Prime Minister 2010-2011

List of party presidents

| President | Term begin | Term end |

|---|---|---|

| Otto Karhi | 1906 | 1909 |

| Kyösti Kallio | 1909 | 1917 |

| Filip Saalasti | 1917 | 1918 |

| Santeri Alkio | 1918 | 1919 |

| Pekka Heikkinen | 1919 | 1940 |

| Viljami Kalliokoski | 1940 | 1945 |

| Vieno Johannes Sukselainen | 1945 | 1964 |

| Johannes Virolainen | 1964 | 1980 |

| Paavo Väyrynen | 1980 | 1990 |

| Esko Aho (first time) | 1990 | 2000 |

| Anneli Jäätteenmäki (first time) | 2000 | 2001 |

| Esko Aho (second time) | 2001 | 2002 |

| Anneli Jäätteenmäki (second time) | 2002 | 2003 |

| Matti Vanhanen | 2003 | 2010 |

| Mari Kiviniemi | 2010 | 2012 |

| Juha Sipilä | 2012- | present day |

Elections

Below is a chart of the results of the Centre Party in Finnish parliamentary elections.

Parliamentary elections

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Municipal elections

|

European parliament

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Presidential elections

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

Sources

- Vares, Vesa; Mikko Uola; Mikko Majander (2006). Demokratian haasteet 1907–1919, article in the book Kansanvalta koetuksella. Helsinki: Edita. ISBN 951-37-4543-0.

- Vares, Vesa (1998). Kuninkaan tekijät: Suomalainen monarkia 1917–1919. Myytti ja todellisuus. Porvoo-Helsinki-Juva: WSOY. ISBN 951-0-23228-9.

References

- ↑ Niemelä, Mikko (13 March 2011). "Perussuomalaisilla hurja tahti: "Jäseniä tulee ovista ja ikkunoista"". Kauppalehti. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ↑ Josep M. Colomer (25 July 2008). Political Institutions in Europe. Routledge. p. 260. ISBN 978-1-134-07354-2.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Nanna Kildal; Stein Kuhnle (7 May 2007). Normative Foundations of the Welfare State: The Nordic Experience. Routledge. p. 74–. ISBN 978-1-134-27283-9.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Svante Ersson; Jan-Erik Lane (28 December 1998). Politics and Society in Western Europe. SAGE. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-7619-5862-8. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 T. Banchoff (28 June 1999). Legitimacy and the European Union. Taylor & Francis. p. 123–. ISBN 978-0-415-18188-4. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ↑ Emil J. Kirchner (3 November 1988). Liberal Parties in Western Europe. Cambridge University Press. p. 408–. ISBN 978-0-521-32394-9. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ↑ Norman Schofield; Gonzalo Caballero (11 June 2011). Political Economy of Institutions, Democracy and Voting. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 319. ISBN 978-3-642-19519-8.

- ↑ Mickelsson, Rauli. Suomen puolueet — historia, muutos ja nykypäivä. Vastapaino, 2007.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Mylly, Juhani. Maalaisliitto-Keskustan historia II. http://www.hs.fi/kirjat/artikkeli/Suomen+keskustanv%C3%A4kev%C3%A4+nuoruusMaalaisliiton+historian+toinen+osa+on+j%C3%A4rjest%C3%B6historian+eliitti%C3%A4/900525165

- ↑ Vares 2006, p. 113.

- ↑ Vares 2006, p. 108

- ↑ Vares 2006, p. 122-126

- ↑ Vares 1998, p. 288-289

- ↑ Siltala, Juha: Lapuan liike ja kyyditykset 1930, 1985, Otava

- ↑ Seppo Zetterberg et al., eds., A Small Giant of the Finnish History / Suomen historian pikkujättiläinen, Helsinki: WSOY, 2003

- ↑ Sakari Virkkunen, Finland's Presidents I / Suomen presidentit I, Helsinki: WSOY, 1994

- ↑ Arter, David (1988). "Liberal parties in Finland". In Kirchner, Emil Joseph. Liberal Parties in Western Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 326–327. ISBN 978-0-521-32394-9.

- ↑ Raunio, Tapio. Department of Political Science and International Relations, University of Tampere, The difficult task of opposing EU in Finland http://www.essex.ac.uk/ECPR/events/jointsessions/paperarchive/turin/ws25/RAUNIO.pdf

- ↑ "Väyrynen ryöpyttää keskustan liberaaleja". Kaleva.fi. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ↑ "Homoliitot: Nämä puolueet sanovat ei". Uusi Suomi. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ↑ Cracking open the numbers in the same-sex marriage vote, YLE 28 November 2014, accessed 5 November 2014.

- ↑ http://www.hs.fi/paakirjoitus/artikkeli/Keskusta+sai+mahdollisuuden+uusiutua/1135265789055

- ↑ "Vaalit 2011". Yle Uutiset. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ↑ "Paikallisyhdistykset". Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ↑ http://www.keskusta.fi/Suomeksi/Keskusta/Keskustan_ihmiset.iw3

- ↑ Steed, Michael; Humphreys, Peter (1988). "Identifying liberal parties". In Kirchner, Emil Joseph. Liberal Parties in Western Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 411. ISBN 978-0-521-32394-9.

External links

- Official website (Finnish)

- Centre Party: Swedish-speaking section (Swedish)

- Website in English (English)

- Youth organizations official website (Finnish)

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||