Causes of World War I

The underlying causes of World War I, which began in the The Balkans in late July 1914, are several. Among these causes were political, territorial, and economic conflicts among the great European powers in the four decades leading up to the war. Additional causes were militarism, a complex web of alliances, imperialism, and nationalism. The immediate origins of the war, however, lay in the decisions taken by statesmen and generals during the July Crisis of 1914 caused by the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie by Gavrilo Princip, an ethnic Serb and Yugoslav nationalist from the group Young Bosnia, which was supported by the Black Hand, a nationalist organization in Serbia.[1]

The crisis came after a long and difficult series of diplomatic clashes among the Great Powers (Italy, France, Germany, Britain, Austria-Hungary and Russia) over European and colonial issues in the decade before 1914 that had left tensions high. In turn these public clashes can be traced to changes in the balance of power in Europe since 1867.[2] The more immediate cause for the war was tensions over territory in the Balkans. Austria-Hungary competed with Serbia and Russia for territory and influence in the region and they pulled the rest of the Great Powers into the conflict through their various alliances and treaties.

Some of the most important long term or structural factors were the growth of nationalism across Europe, unresolved territorial disputes, an intricate system of alliances, the perceived breakdown of the balance of power in Europe,[3][4] convoluted and fragmented governance, the arms races of the previous decades, previous military planning,[5] imperial and colonial rivalry for wealth, power and prestige, and economic and military rivalry in industry and trade – e.g., the Pig War between Austria-Hungary and Serbia. Other causes that came into play during the diplomatic crisis that preceded the war included misperceptions of intent (e.g., the German belief that Britain would remain neutral) and delays and misunderstandings in diplomatic communications. Historians in recent years have downplayed economic rivalries and have portrayed the international business community as a force for peace. War would hurt business.[6]

The various categories of explanation for World War I correspond to different historians' overall methods. Most historians and popular commentators include causes from more than one category of explanation to provide a rounded account of the causes of the war. The deepest distinction among these accounts is between stories that see it as the inevitable and predictable outcome of certain factors, and those that describe it as an arbitrary and unfortunate mistake. In attributing causes for the war, historians and academics had to deal with an unprecedented flood of memoirs and official documents, released as each country involved tried to avoid blame for starting the war. Early releases of information by governments, particularly those released for use by the "Commission on the Responsibility of the Authors of the War" were shown to be incomplete and biased. In addition some documents, especially diplomatic cables between Russia and France, were found to have been doctored.

Background

In November 1912, Russia, which had been humiliated because of its inability to support Serbia during the Bosnian crisis of 1908 or the First Balkan War, announced a major reconstruction of its military.

On November 29, German Foreign Secretary Gottlieb von Jagow told the Reichstag (the German parliament), that "If Austria is forced, for whatever reason, to fight for its position as a Great Power, then we must stand by her."[7] As a result, British Foreign Secretary Sir Edward Grey responded by warning Prince Karl Lichnowsky, the German Ambassador in London, that if Germany offered Austria a "blank cheque" for war in the Balkans, then "the consequences of such a policy would be incalculable." To reinforce this point, R. B. Haldane, the Lord Chancellor, met with Prince Lichnowsky to offer an explicit warning that if Germany were to attack France, Britain would intervene in France's favour.[7]

With the recently announced Russian military reconstruction and certain British communications, the possibility of war was a leading topic at the German Imperial War Council of 8 December 1912 in Berlin, an informal meeting of some of Germany's top military leadership called on short notice by Kaiser Wilhelm II.[7] Attending the conference were the Kaiser, Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz – the Naval State Secretary, Admiral Georg Alexander von Müller, the Chief of the German Imperial Naval Cabinet (Marinekabinett), General Helmuth von Moltke – the Army's Chief of Staff, Admiral August von Heeringen – the Chief of the Naval General Staff and General Moriz von Lyncker, the Chief of the German Imperial Military Cabinet.[7] The presence of the leaders of both the German Army and Navy at this War Council attests to its importance. However, Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg and General Josias von Heeringen, the Prussian Minister of War, were not invited.[8]

Wilhelm II called British balance of power principles "idiocy," but agreed that Haldane's statement was a "desirable clarification" of British policy.[7] His opinion was that Austria should attack Serbia that December, and if "Russia supports the Serbs, which she evidently does ... then war would be unavoidable for us, too," [7] and that would be better than going to war after Russia completed the massive modernization and expansion of their army that they had just begun. Moltke agreed. In his professional military opinion "a war is unavoidable and the sooner the better".[7] Moltke "wanted to launch an immediate attack".[9]

Both Wilhelm II and the Army leadership agreed that if a war were necessary it were best launched soon. Tirpitz, however, asked for a "postponement of the great fight for one and a half years"[7] because the Navy was not ready for a general war that included Britain as an opponent. He insisted that the completion of the construction of the U-boat base at Heligoland and the widening of the Kiel Canal were the Navy's prerequisites for war.[7] As the British historian John Röhl has commented, the date for completion of the widening of the Kiel Canal was the summer of 1914.[9] Though Moltke objected to the postponement of the war as unacceptable, Wilhelm sided with Tirpitz.[7] Moltke "agreed to a postponement only reluctantly."[9]

Historians more sympathetic to the government of Wilhelm II often reject the importance of this War Council as only showing the thinking and recommendations of those present, with no decisions taken. They often cite the passage from Admiral Müller's diary, which states: "That was the end of the conference. The result amounted to nothing."[9] Certainly the only decision taken was to do nothing.

Historians more sympathetic to the Entente, such as Röhl, sometimes rather ambitiously interpret these words of Admiral Müller (an advocate of launching a war soon) as saying that "nothing" was decided for 1912–13, but that war was decided on for the summer of 1914.[9] Röhl is on safer ground when he argues that even if this War Council did not reach a binding decision—which it clearly did not—it did nonetheless offer a clear view of their intentions,[9] or at least their thoughts, which were that if there was going to be a war, the German Army wanted it before the new Russian armaments program began to bear fruit.[9] Entente sympathetic historians such as Röhl see this conference, in which "The result amounted to nothing,"[9] as setting a clear deadline for a war to begin, namely the summer of 1914.[9]

With the November 1912 announcement of the Russian Great Military Programme, the leadership of the German Army began clamoring even more strongly for a "preventive war" against Russia.[7][10] Moltke declared that Germany could not win the arms race with France, Britain and Russia, which she herself had begun in 1911, because the financial structure of the German state, which gave the Reich government little power to tax, meant Germany would bankrupt herself in an arms race.[7] As such, Moltke from late 1912 onwards was the leading advocate for a general war, and the sooner the better.[7]

Throughout May and June 1914, Moltke engaged in an "almost ultimative" demand for a German "preventive war" against Russia in 1914.[9] The German Foreign Secretary, Gottlieb von Jagow, reported on a discussion with Moltke at the end of May 1914:

"Moltke described to me his opinion of our military situation. The prospects of the future oppressed him heavily. In two or three years Russia would have completed her armaments. The military superiority of our enemies would then be so great that he did not know how he could overcome them. Today we would still be a match for them. In his opinion there was no alternative to making preventive war in order to defeat the enemy while we still had a chance of victory. The Chief of the General Staff therefore proposed that I should conduct a policy with the aim of provoking a war in the near future."[9]

The new French President Raymond Poincaré, who took office in 1913, was favourable to improving relations with Germany.[11] In January 1914 Poincaré became the first French President to dine at the German Embassy in Paris.[11] Poincaré was more interested in the idea of French expansion in the Middle East than a war of revenge to regain Alsace-Lorraine. Had the Reich been interested in improved relations with France before August 1914, the opportunity would have been available, but the leadership of the Reich lacked such interests, and preferred a policy of war to destroy France. Because of France's smaller economy and population, by 1913 French leaders had largely accepted that France by itself could never defeat Germany.[12]

In May 1914, Serbian politics were polarized between two factions, one headed by the Prime Minister Nikola Pašić, and the other by the radical nationalist chief of Military Intelligence, Colonel Dragutin Dimitrijević, known by his codename Apis.[13] In that month, due to Colonel Dimitrigjevic's intrigues, King Peter dismissed Pašić's government.[13] The Russian Minister in Belgrade intervened to have Pašić's government restored.[13] Pašić, though he often talked tough in public, knew that Serbia was near-bankrupt and, having suffered heavy casualties in the Balkan Wars and in the suppression of a December 1913 Albanian revolt in Kosovo, needed peace.[13] Since Russia also favoured peace in the Balkans, from the Russian viewpoint it was desirable to keep Pašić in power.[13] It was in the midst of this political crisis that politically powerful members of the Serbian military armed and trained three Bosnian students as assassins and sent them into Austria-Hungary.[14]

Domestic political factors

German domestic politics

Left-wing parties, especially the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) made large gains in the 1912 German election. German government at the time was still dominated by the Prussian Junkers who feared the rise of these left-wing parties. Fritz Fischer famously argued that they deliberately sought an external war to distract the population and whip up patriotic support for the government.[15] Indeed, one German military leader said that a war was ‘desirable in order to escape from difficulties at home and abroad’ and a Prussian conservative leader even argued that ‘a war would strengthen patriarchal order’.[16] Russia was in the midst of a large-scale military build-up and reform that they intended to complete in 1916–1917.

Other authors argue that German conservatives were ambivalent about a war, worrying that losing a war would have disastrous consequences, and even a successful war might alienate the population if it were lengthy or difficult.[17]

French domestic politics

The situation in France was quite different from that in Germany; in France, war appeared to be a gamble. Forty years after the loss of Alsace-Lorraine a vast number of French were still angered by it, as well as by the humiliation of being compelled to pay a large reparation to Germany. The diplomatic alienation of France orchestrated by Germany prior to World War I caused further resentment in France. Nevertheless, the leaders of France recognized Germany's military advantage, as Germany had nearly twice the population and a better equipped army. At the same time, the episodes of the Tangier Crisis in 1905 and the Agadir Crisis in 1911 had given France an indication that war with Germany could come if Germany continued to oppose French colonial expansionism.

France was politically polarized; the left-wing socialists led by Jean Jaurès pushed for peace against nationalists on the right like Paul Déroulède who called for revenge against Germany. France in 1914 had never been so prosperous and influential in Europe since 1870, nor its military so strong and confident in its leaders, emboldened by its success in North Africa and the overall pacification of its vast colonial empire. The Entente Cordiale of 1904 with Britain held firm, and was supported by mutual interests abroad and strong economic ties. Russia had fled the triple crown alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary because of disagreements with Austria-Hungary over policy in the Balkans. Russia also hoped that large French investments in its industry and infrastructures coupled with an important military partnership would prove themselves profitable and durable.

The foreign ministry was filled with expert diplomats, but there was great turnover at the top. In the 18 months before the war there were six foreign ministers. The leadership was prepared to fight Germany and attempt to gain back the provinces of Alsace and Lorraine lost in 1871. It is important to note however, that France could never have permitted itself to initiate a war with Germany, as its military pact with Britain was only purely defensive. The assumption that Germany would not violate neutral Belgium was a serious blunder in French planning.[18]

Austrian Empire and Austria-Hungary

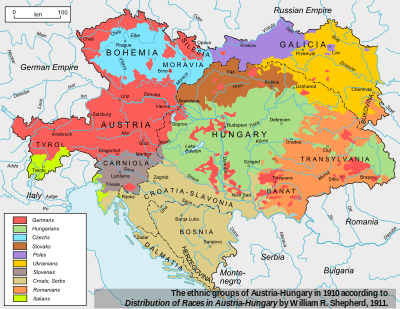

In 1867, the Austrian Empire fundamentally changed its governmental structure, becoming the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary. For hundreds of years, the empire had been run in an essentially feudal manner with a German-speaking aristocracy at its head. However, with the threat represented by an emergence of nationalism within the empire's many component ethnicities, some elements, including Emperor Franz Joseph, decided that a compromise was required to preserve the power of the German aristocracy. In 1867, the Ausgleich was agreed on, which made the Hungarian elite in Hungary almost equal partners in the government of Austria-Hungary.

This arrangement fostered a high degree of dissatisfaction amongst many in the traditional German-speaking ruling classes.[19] Some of them considered the Ausgleich to have been a calamity because it often frustrated their intentions in the governance of Austria-Hungary.[20] For example, it was extremely difficult for Austria-Hungary to form a coherent foreign policy that suited the interests of both the German and Hungarian elite.[21]

As a result, there was widespread advocacy of a war with Serbia in leading circles both at Vienna and at Budapest.

Some reasoned that dealing with political deadlock required that more Slavs be brought into Austria-Hungary to dilute the power of the Hungarian elite. With more Slavs, the South Slavs of Austria-Hungary could force a new political compromise in which the Germans could play the Hungarians against the South Slavs.[22] Other variations on this theme existed, but the essential idea was to cure internal stagnation through external conquest.

Another fear was that the South Slavs, primarily under the leadership of Serbia, were organizing for a war against Austria-Hungary, and even all of Germanic civilization. Some leaders, such as Conrad von Hötzendorf, argued that Serbia must be dealt with before it became too powerful to defeat militarily.[23]

A powerful contingent within the Austro-Hungarian government was motivated by these thoughts and advocated war with Serbia long before the war began. Prominent members of this group included Leopold von Berchtold, Alexander von Hoyos, and Johann von Forgách. Although many other members of the government, notably Franz Ferdinand, Franz Joseph, and many Hungarian politicians did not believe that a violent struggle with Serbia would necessarily solve any of Austria-Hungary's problems, the hawkish elements did exert a strong influence on government policy, holding key positions.[22]

Samuel R. Williamson has emphasized the role of Austria-Hungary in starting the war. Convinced Serbian nationalism and Russian Balkan ambitions were disintegrating the Empire, Austria-Hungary hoped for a limited war against Serbia and that strong German support would force Russia to keep out of the war and weaken its Balkan prestige.[24]

International relations

Imperialism

Marxists typically attributed the start of the war to imperialism. "Imperialism," argued Lenin, "is the monopoly stage of capitalism." He thought the monopoly capitalists went to war to control markets and raw materials.[25]

Britain especially with its vast worldwide British Empire was a main example, although it entered the war later than the other key players on the issue of Belgium. Britain also had an "informal empire" based on trade in neutral countries. It grew rich in part from its success in trade in foreign resources, markets, territories, and people, and Germany was jealous because its much smaller empire was much poorer. John Darwin argues the British Empire was distinguished by the adaptability of its builders. Darwin says, "The hallmark of British imperialism was its extraordinary versatility in method, outlook and object." The British tried to avoid military action in favour of reliance on networks of local elites and businessmen who voluntarily collaborated and in turn gained authority (and military protection) from British recognition.[26] France, Germany, the Netherlands, and Italy all hoped to emulate the British model, and the United States became a latecomer in 1898. In all countries the quest for national prestige strengthened imperial motives. Their frustrated ambitions, and British policies of strategic exclusion created tensions. Commercial interests contributed substantially to rivalries during the Scramble for Africa after 1880. Africa became the scene of sharpest conflict between certain French, German and British imperial interests.

Rivalries for not just colonies, but colonial trade and trade routes developed between the emerging economic powers and the incumbent great powers. Although still argued differently according to historical perspectives on the path to war, this rivalry was illustrated in the Berlin-Baghdad Railway, which would have given German industry access[27] to Mesopotamia's suspected "rich oil fields, and [known] extensive asphalt deposits",[28] as well as German trade a southern port in the Persian Gulf. A history of this railroad describes the German interests in countering the British Empire at a global level, and Turkey's interest in countering their Russian rivals at a regional level.[29] As stated by a contemporary 'man on the ground' at the time, Jastrow wrote, "It was felt in England that if, as Napoleon is said to have remarked, Antwerp in the hands of a great continental power was a pistol leveled at the English coast, Baghdad and the Persian Gulf in the hands of Germany (or any other strong power) would be a 42-centimetre gun pointed at India." [30] On the other side, "Public opinion in Germany was feasting on visions of Cairo, Baghdad, and Tehran, and the possibility of evading the British blockade through outlets to the Indian Ocean."[31] Britain's initial strategic exclusion of others from northern access to a Persian Gulf port in the creation of Kuwait by treaty as a protected, subsidized client state showed political recognition of the importance of the issue.[32] On June 15, 1914, Britain and Germany signed an agreement on the issue of the Baghdad Railway, which Britain had earlier signed with Turkey, to open access to its use, to add British representation on the Board of the Railway, and restrict access by rail to the Persian Gulf.[33][34][35]

The Railway issue did not play a role in the failed July 1914 negotiations.[36]

Germany's leader Otto von Bismarck disliked the idea of an overseas empire, but pursued a colonial policy in response to domestic political demands. Bismarck supported French colonization in Africa because it diverted government attention and resources away from continental Europe and revanchism. After 1890 Bismarck's successor, Leo von Caprivi, was the last German Chancellor who was successful in calming Anglo-German tensions. After Caprivi left office in 1894, Germany's bellicose "New Course" in foreign affairs controlled by Kaiser Wilhelm. Bombastic and impetuous, the Kaiser made tactless pronouncements on sensitive topics without consulting his ministers, culminating in a disastrous Daily Telegraph interview that cost him most of his power inside the German government in 1908. Langer et al. (1968) emphasize the negative international consequences of Wilhelm's erratic personality:

- He believed in force, and the 'survival of the fittest' in domestic as well as foreign politics... William was not lacking in intelligence, but he did lack stability, disguising his deep insecurities by swagger and tough talk. He frequently fell into depressions and hysterics... William's personal instability was reflected in vacillations of policy. His actions, at home as well as abroad, lacked guidance, and therefore often bewildered or infuriated public opinion. He was not so much concerned with gaining specific objectives, as had been the case with Bismarck, as with asserting his will. This trait in the ruler of the leading Continental power was one of the main causes of the uneasiness prevailing in Europe at the turn-of-the-century.[37]

The status of Morocco had been guaranteed by international agreement, and when France attempted to greatly expand its influence there without the assent of all the other signatories Germany opposed it prompting the Moroccan Crises, the Tangier Crisis of 1905 and the Agadir Crisis of 1911. The intent of German policy was to drive a wedge between the British and French, but in both cases produced the opposite effect and Germany was isolated diplomatically, most notably lacking the support of Italy despite Italian membership in the Triple Alliance. The French protectorate over Morocco was established officially in 1912.

In 1914, however, the African scene was peaceful. The continent was almost fully divided up by the imperial powers (with only Liberia and Ethiopia still independent). There were no major disputes there pitting any two European powers against each other.[38]

Social Darwinism

By the late 19th century a new school of thought, later known as Social Darwinism became popular among intellectuals and political leaders. It emphasized that competition was natural in a biological sense. In nature there was the 'survival of the fittest organism' and so too in political geography the fittest nation would win out. Nationalism made it a competition between peoples, nations or races rather than kings and elites.[39] Social Darwinism carried a sense of inevitability to conflict and downplayed the use of diplomacy or international agreements to end warfare. It tended to glorify warfare, taking the initiative and the warrior male role.[40] Social Darwinism played an important role across Europe, but J. Leslie has argued that it played a critical and immediate role in the strategic thinking of some important, hawkish members of the Austro-Hungarian government.[41]

Web of alliances

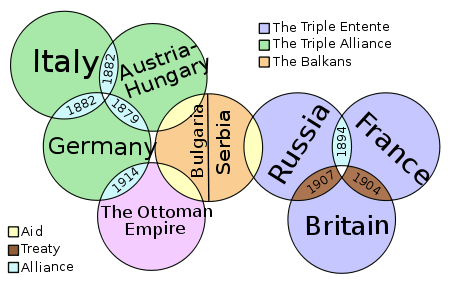

A loose web of alliances around the European nations existed (many of them requiring participants to agree to collective defense if attacked):

- Treaty of London, 1839, about the neutrality of Belgium

- German-Austrian treaty (1879) or Dual Alliance

- Italy joining Germany and Austria in 1882

- Franco-Russian Alliance (1894)

- The "Entente Cordiale" between Britain and France (1904), which left the northern coast of France undefended, and the separate "entente" between Britain and Russia (1907) that formed the Triple Entente

This complex set of treaties binding various players in Europe together before the war sometimes is thought to have been misunderstood by contemporary political leaders. The traditionalist theory of "Entangling Alliances" has been shown to be mistaken. The Triple Entente between Russia, France and the United Kingdom did not in fact force any of those powers to mobilize because it was not a military treaty. Mobilization by a relatively minor player would not have had a cascading effect that could rapidly run out of control, involving every country. The crisis between Austria-Hungary and Serbia could have been a localized issue.

The chain of events

- June 28, 1914: Serbian irredentists assassinate Archduke Franz Ferdinand of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

- June 28–29: Anti-Serb riots in Sarajevo

- July 23: Austria-Hungary, following their own secret enquiry, sends an ultimatum to Serbia, containing several very severe demands. In particular, they gave only forty-eight hours to comply. While both Great Britain and Russia sympathized with many of the demands, both agreed the timescale was far too short. Both nevertheless advised Serbia to comply.

- July 24: Germany officially declares support for Austria's position.

- July 24: Sir Edward Grey, speaking for the British government, asks that Germany, France, Italy and Great Britain, "who had no direct interests in Serbia, should act together for the sake of peace simultaneously."[42]

- July 25: The Serbian government replies to Austria, and agrees to most of the demands. However, certain demands brought into question her survival as an independent nation. On these points they asked that the Hague Tribunal arbitrate.

- July 25: Russia enters a period preparatory to war and mobilization begins on all frontiers. Government decides on a partial mobilization in principle to begin on July 29.

- July 25: Serbia mobilizes its army; responds to Austro-Hungarian démarche with less than full acceptance; Austria-Hungary breaks diplomatic relations with Serbia.

- July 26: Serbia reservists accidentally violate Austro-Hungarian border at Temes-Kubin.[43]

- July 26: Russia having agreed to stand aside whilst others conferred, a meeting is organised to take place between ambassadors from Great Britain, Germany, Italy and France to discuss the crisis. Germany declines the invitation.

- July 27: Sir Edward Grey meets the German ambassador independently. A telegram to Berlin after the meeting states, "Other issues might be raised that would supersede the dispute between Austria and Serbia ... as long as Germany would work to keep peace I would keep closely in touch."

- July 28: Austria-Hungary, having failed to accept Serbia's response of the 25th, declares war on Serbia. Mobilisation against Serbia begins.

- July 29: Russian general mobilization is ordered, and then changed to partial mobilization.

- July 29: Sir Edward Grey appeals to Germany to intervene to maintain peace.

- July 29: The British Ambassador in Berlin, Sir Edward Goschen, is informed by the German Chancellor that Germany is contemplating war with France, and furthermore, wishes to send its army through Belgium. He tries to secure Britain's neutrality in such an action.

- July 30: Russian general mobilization is reordered at 5:00 P.M.

- July 31: Austrian general mobilization is ordered.

- July 31: Germany enters a period preparatory to war.

- July 31: Germany sends an ultimatum to Russia, demanding that they halt military preparations within twelve hours.

- July 31: Both France and Germany are asked by Britain to declare their support for the ongoing neutrality of Belgium. France agrees to this. Germany does not respond.

- July 31: Germany asks France, whether it would stay neutral in case of a war Germany vs. Russia

- August 1 (3 A.M.): King George V of Great Britain personally telegraphs Tsar Nicholas II of Russia.

- August 1: French general mobilization is ordered, deployment Plan XVII chosen.

- August 1: German general mobilization is ordered, deployment plan 'Aufmarsch II West' chosen.

- August 1: Germany declares war against Russia.

- August 1: The Tsar responds to the king's telegram, stating, "I would gladly have accepted your proposals had not the German ambassador this afternoon presented a note to my Government declaring war."

- August 2: Germany and the Ottoman Empire sign a secret treaty[44] entrenching the Ottoman–German Alliance.

- August 3: Germany, after France declines (See Note) its demand to remain neutral,[45] declares war on France. Germany states to Belgium that she would "treat her as an enemy" if she did not allow free passage of German troops across her lands.

- August 3: Britain, expecting German naval attack on the northern French coast, states that Britain would give "... all the protection in its powers."

- August 4: Germany implements offensive operation inspired by Schlieffen Plan.

- August 4 (midnight): Having failed to receive notice from Germany assuring the neutrality of Belgium, Britain declares war on Germany.

- August 6: Austria-Hungary declares war on Russia.

- August 23: Japan, honouring the Anglo-Japanese Alliance, declares war on Germany.

- August 25: Japan declares war on Austria-Hungary.

Note: French Prime Minister René Viviani merely replied to the German ultimatum that, "France will act in accordance with her interests."[45] Had the French agreed to remain neutral, the German Ambassador was authorized to ask the French to temporarily surrender the Fortresses of Toul and Verdun as a guarantee of neutrality.

Arms race

By the 1870s or 1880s all the major powers were preparing for a large-scale war, although none expected one. Britain focused on building up its Royal Navy, already stronger than the next two navies combined. Germany, France, Austria, Italy and Russia, and some smaller countries, set up conscription systems whereby young men would serve from 1 to three years in the army, then spend the next 20 years or so in the reserves with annual summer training. Men from higher social statuses became officers. Each country devised a mobilisation system whereby the reserves could be called up quickly and sent to key points by rail. Every year the plans were updated and expanded in terms of complexity. Each country stockpiled arms and supplies for an army that ran into the millions. Germany in 1874 had a regular professional army of 420,000 with an additional 1.3 million reserves. By 1897 the regular army was 545,000 strong and the reserves 3.4 million. The French in 1897 had 3.4 million reservists, Austria 2.6 million, and Russia 4.0 million. The various national war plans had been perfected by 1914, albeit with Russia and Austria trailing in effectiveness. Recent wars (since 1865) had typically been short—a matter of months. All the war plans called for a decisive opening and assumed victory would come after a short war; no one planned for or was ready for the food and munitions needs of a long stalemate as actually happened in 1914–18.[46][47]

As David Stevenson has put it, "A self-reinforcing cycle of heightened military preparedness ... was an essential element in the conjuncture that led to disaster ... The armaments race ... was a necessary precondition for the outbreak of hostilities." David Herrmann goes further, arguing that the fear that "windows of opportunity for victorious wars" were closing, "the arms race did precipitate the First World War." If Archduke Franz Ferdinand had been assassinated in 1904 or even in 1911, Herrmann speculates, there might have been no war. It was "... the armaments race ... and the speculation about imminent or preventive wars" that made his death in 1914 the trigger for war.[48]

One of the aims of the First Hague Conference of 1899, held at the suggestion of Emperor Nicholas II, was to discuss disarmament. The Second Hague Conference was held in 1907. All the signatories except for Germany supported disarmament. Germany also did not want to agree to binding arbitration and mediation. The Kaiser was concerned that the United States would propose disarmament measures, which he opposed. All parties tried to revise international law to their own advantage.[49]

Anglo–German naval race

Historians have debated the role of the German naval build-up as the principal cause of deteriorating Anglo-German relations. In any case Germany never came close to catching up with Britain.

Supported by Wilhelm II's enthusiasm for an expanded German navy, Grand Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz championed four Fleet Acts from 1898 to 1912, and, from 1902 to 1910, the Royal Navy embarked on its own massive expansion to keep ahead of the Germans. This competition came to focus on the revolutionary new ships based on the Dreadnought, which was launched in 1906, and which gave Britain a battleship that far outclassed any other in Europe.[50][51]

| The naval strength of the powers in 1914 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Personnel | Large Naval Vessels (Dreadnoughts) |

Tonnage |

| Russia | 54,000 | 4 | 328,000 |

| France | 68,000 | 10 | 731,000 |

| Britain | 209,000 | 29 | 2,205,000 |

| TOTAL | 331,000 | 43 | 3,264,000 |

| Germany | 79,000 | 17 | 1,019,000 |

| Austria-Hungary | 16,000 | 4 | 249,000 |

| TOTAL | 95,000 | 21 | 1,268,000 |

| (Source: Ferguson 1999, p. 85) | |||

The overwhelming British response proved to Germany that its efforts were unlikely to equal the Royal Navy. In 1900, the British had a 3.7:1 tonnage advantage over Germany; in 1910 the ratio was 2.3:1 and in 1914, 2.1:1. Ferguson argues that, "So decisive was the British victory in the naval arms race that it is hard to regard it as in any meaningful sense a cause of the First World War."[52] This ignores the fact that the Kaiserliche Marine had narrowed the gap by nearly half, and that the Royal Navy had long intended to be stronger than any two potential opponents; the United States Navy was in a period of growth, making the German gains very ominous.

In Britain in 1913, there was intense internal debate about new ships due to the growing influence of John Fisher's ideas and increasing financial constraints. In early-mid-1914 Germany adopted a policy of building submarines instead of new dreadnoughts and destroyers, effectively abandoning the race, but kept this new policy secret to delay other powers following suit.[53]

Though the Germans abandoned the naval race, as such, before the war broke out, it had been one of the chief factors in Britain's decision to join the Triple Entente and therefore important in the formation of the alliance system as a whole.

Russian interests in Balkans and Ottoman Empire

The main Russian goals included strengthening its role as the protector of Eastern Christians in the Balkans (such as the Serbians).[54] Although Russia enjoyed a booming economy, growing population, and large armed forces, its strategic position was threatened by an expanding Turkish military trained by German experts using the latest technology. The start of the war renewed attention of old goals: expelling the Turks from Constantinople, extending Russian dominion into eastern Anatolia and Persian Azerbaijan, and annexing Galicia. These conquests would assure Russian predominance in the Black Sea and access to the Mediterranean.[55]

Technical and military factors

Over by Christmas

When the war began both sides believed, and publicly stated, that the war would end soon. The Kaiser told his troops that they would be "... home before the leaves have fallen from the trees", and one German officer said he expected to be in Paris by Sedantag, about six weeks away. Germany only stockpiled enough potassium nitrate for gunpowder for six months;[56] without the just-developed Haber process, Germany might have collapsed by 1916.[57] Russian officers similarly expected to be in Berlin in six weeks, and those who suggested that the war would last for six months were considered pessimists. Von Moltke and his French counterpart Joseph Joffre were among the few who expected a long war, but neither formally adjusted his nation's military plans accordingly. The new British Secretary of State for War Lord Kitchener was the only leading official on either side to both expect a long war ("three years" or longer, he told an amazed colleague) and acted accordingly, immediately building an army of millions of soldiers who would fight for years.[56]

Some authors such as Niall Ferguson argue that the belief in a swift war has been greatly exaggerated since the war.[17] He argues that the military planners, especially in Germany, were aware of the potential for a long war, as shown by the Willy–Nicky telegraphic correspondence between the emperors of Russia and Germany. He also argues that most informed people considered a swift war unlikely. However, it was in the belligerent governments' interests to convince their populaces, through skillful propaganda, that the war would be brief. Such a message encouraged men to join the offensive, made the war seem less serious, and promoted general high spirits.

Primacy of the offensive and war by timetable

Military theorists of the time generally held that seizing the offensive was extremely important. This theory encouraged all belligerents to strike first to gain the advantage. This attitude shortened the window for diplomacy. Most planners wanted to begin mobilization as quickly as possible to avoid being caught on the defensive.

Some historians assert that mobilization schedules were so rigid that once it was begun, they could not be cancelled without massive disruption of the country and military disorganization and so diplomatic overtures conducted after the mobilizations had begun were ignored.[58] However in practice these timetables were not always decisive. The Tsar ordered general mobilization canceled on July 29 despite his chief of staff's objections that this was impossible.[59] A similar cancellation was made in Germany by the Kaiser on August 1 over the same objections,[60] although in theory Germany should have been the country most firmly bound by its mobilization schedule. Barbara Tuchman offers another explanation in the Guns of August—that the nations involved were concerned about falling behind their adversaries in mobilization. According to Tuchman, war pressed against every frontier. Suddenly dismayed, governments struggled and twisted to fend it off. It was no use. Agents at frontiers were reporting every cavalry patrol as a deployment to beat the mobilization gun. General staffs, goaded by their relentless timetables, were pounding the table for the signal to move lest their opponents gain an hour's head start. Appalled on the brink, the chiefs of state ultimately responsible for their country's fate attempted to back away, but the pull of military schedules dragged them forward.[61]

Schlieffen Plan

Germany, in contrast to Austria-Hungary, had by 1905 no real territorial goals within Europe. But Germany's military-strategic situation was poor as Austria-Hungary was a weak ally and France and Russia grew closer. Neither Germany nor Austria-Hungary were able to increase spending upon their armed forces due to deadlock in their countries' legislatures. This meant that Germany's strategic situation worsened as both France and Russia continually increased their military spending throughout this period. Accordingly, the improvement of the Franco-Russian forces is not considered to be part of an 'arms race'.

The German General Staff under Count & General Alfred von Schlieffen devised three different deployment plans and operational-guides for war. Two addressed the case of a war with a Franco-Russian alliance and reconciled a defensive strategy with counter-offensive operations. Aufmarsch II West favoured a counter-offensive against the French offensive before moving to deal with the Russian and Aufmarsch I Ost favoured defeating the Russian offensive before moving to deal with the French. The greater density of railway-infrastructure in the west meant that Schlieffen himself favoured Aufmarsch II West as it would allow a greater force to be deployed there and thus a greater victory to be won over the French attackers.[62]

But the third plan, Aufmarsch I West or 'The Schlieffen Plan', detailed an offensive operation. This plan catered for an isolated Franco-German war in which Italy and Austria-Hungary would side with Germany but Russia would remain neutral. This deployment plan was made with an offensive operation through the southern Netherlands and northern Belgium in mind, with Italian and Austro-Hungarian forces being expected to defend Germany itself during this operation. Ideally the French Army would stand fast against the German army and have a large part of its force enveloped and forced to surrender. But if the French retreated then the German army could pursue and breach France's 'second defensive area', reducing its defensive value.[63]

However, Aufmarsch I West became increasing unsuitable as it became clear that an isolated Franco-German war was an impossibility. With Russia and Britain both expected to participate, Italian and Austro-Hungary troops could not be used to defend Germany as per the plan. Moreover, East Prussia and the north-German coastline would be completely undefended as the entire German army would be deployed west of the Rhine. Accordingly, Aufmarsch I West was effectively retired shortly after Schlieffen himself did so in 1905.

Schlieffen's successor, Helmuth von Moltke the Younger, did not think that a defensive strategy suited Germany's strategic needs. He decided that the offensive operation of Aufmarsch I West could be applied to the plan Aufmarsch II West, even though no Italian or Austro-Hungarian help would be forthcoming and at least a fifth of the German Army would have to be deployed elsewhere to defend against British raids and a Russian offensive against East Prussia. Holmes is of the opinion that this force was too weak to breach the French 'second fortified area', meaning that if the French Army chose to retreat rather than stand its ground then the entire operation would fail to appreciably improve Germany's strategic situation (as per Schlieffen's goals for such an operation, albeit following on from the Aufmarsch I West deployment).[64]

The significance of German War Planning is that despite having a number of alternatives Moltke chose to launch an offensive that he should have known could not achieve its nominal objectives[65] - though Tuchman has noted that Moltke was one of the few senior military figures to consider a long war, and despite the failure of the offensive German forces did manage to occupy economically important Franco-Belgian territory.[56] Most of the deployments and operations available to him, including Aufmarsch II Ost which was of his own devising, were both defensive and could decisively alter the strategic balance in Germany's power (if executed successfully) through the destruction of the Franco-Russian Entente's attacking forces. Moltke's choice was particularly dangerous given that the main French deployment plan, Plan XVII, was designed specifically to counter the Schlieffen Plan. Plan XVII deployed the bulk of the French Army on the Franco-Belgian border, allowing an offensive operation through southern Belgium and into Germany. If successful, this would have trapped the German Army in northern Belgium. The adoption of Plan XVII in 1913 was combined with a diplomatic initiative to ensure that the Russians would launch an invasion of East Prussia to coincide with it. Accordingly, the first battles of the war were fought in Germany, southern Belgium, and East Prussia.

British security issues

In explaining why neutral Britain went to war with Germany, Paul Kennedy, in The Rise of the Anglo-German Antagonism, 1860–1914, claimed that it was critical for war that Germany become economically more powerful than Britain, but he played down the disputes over economic trade imperialism, the Baghdad Railway, confrontations in Eastern Europe, high-charged political rhetoric and domestic pressure-groups. Germany's reliance time and again on sheer power, while Britain increasingly appealed to moral sensibilities, played a role, especially in seeing the invasion of Belgium as a necessary military tactic or a profound moral crime. The German invasion of Belgium was not important because the British decision had already been made and the British were more concerned with the fate of France.[66] Kennedy argues that by far the main reason was London's fear that a repeat of 1870—when Prussia and the German states smashed France—would mean Germany, with a powerful army and navy, would control the English Channel, and northwest France. British policy makers insisted that would be a catastrophe for British security.[67]

Specific events

Franco-German tensions

Some of the distant origins of World War I can be seen in the results and consequences of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870–71, over four decades before. The Germans won decisively and set up a powerful Empire, while France went into chaos and military decline for years. A legacy of animosity grew between France and Germany following the German annexation of Alsace-Lorraine. The annexation caused widespread resentment in France, giving rise to the desire for revenge, known as revanchism. French sentiments wanted to avenge military and territorial losses and the displacement of France as the pre-eminent continental military power. French defeat in the war had sparked political instability, culminating in a revolution and the formation of the French Third Republic.

Bismarck was wary of French desire for revenge; he achieved peace by isolating France and balancing the ambitions of Austria-Hungary and Russia in the Balkans. During his later years he tried to placate the French by encouraging their overseas expansion. However, anti-German sentiment remained. A Franco-German colonial entente that was made in 1884 in protest of an Anglo-Portuguese agreement in West Africa proved short-lived after a pro-imperialist government under Jules Ferry in France fell in 1885.

France eventually recovered from its defeat, paid its war indemnity, and rebuilt its military strength again. But it was smaller than Germany in terms of population, and thus felt insecure next to its more powerful neighbor.

Austrian-Serbian tensions and Bosnian Annexation Crisis

One night between 10/11 June 1903, a group of Serbian officers assassinated unpopular King Alexander I of Serbia. The Serbian parliament elected Peter Karađorđević as the new king of Serbia. The consequence of this dynastic change had Serbia relying on Russia and France rather than on Austria-Hungary, as had been the case during rule of the Obrenović dynasty. Serbian desire to relieve itself of Austrian influence provoked the Pig War, an economic conflict, from which Serbia eventually came out as the victor.

Austria-Hungary, desirous of solidifying its position in Bosnia-Herzegovina, annexed the provinces on 6 October 1908.[68] The annexation set off a wave of protests and diplomatic manoeuvres that became known as the Bosnian crisis, or annexation crisis. The crisis continued until April 1909, when the annexation received grudging international approval through amendment of the Treaty of Berlin. During the crisis, relations between Austria-Hungary, on the one hand, and Russia and Serbia, on the other, were permanently damaged.

After an exchange of letters outlining a possible deal, Russian Foreign Minister Alexander Izvolsky and Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister Alois Aehrenthal met privately at Buchlau Castle in Moravia on 16 September 1908. At Buchlau the two agreed that Austria-Hungary could annex the Ottoman provinces of Bosnia and Herzegovina, which Austria-Hungary occupied and administered since 1878 under a mandate from the Treaty of Berlin. In return, Austria-Hungary would withdraw its troops from the Ottoman Sanjak of Novibazar and support Russia in its efforts to amend the Treaty of Berlin to allow Russian war ships to navigate the Straits of Constantinople during times of war. The two jointly agreed not to oppose Bulgarian independence.

While Izvolsky moved slowly from capital to capital vacationing and seeking international support for opening the Straits, Bulgaria and Austria-Hungary moved swiftly. On 5 October, Bulgaria declared its independence from the Ottoman Empire. The next day, Austria-Hungary annexed Bosnia-Herzegovina. On 7 October, Austria-Hungary announced its withdrawal from the Sanjak of Novi Pazar. Russia, unable to obtain Britain's assent to Russia's Straits proposal, joined Serbia in assuming an attitude of protest. Britain lodged a milder protest, taking the position that annexation was a matter concerning Europe, not a bilateral issue, and so a conference should be held. France fell in line behind Britain. Italy proposed that the conference be held in Italy. German opposition to the conference and complex diplomatic maneuvering scuttled the conference. On 20 February 1909, the Ottoman Empire acquiesced to the annexation and received ₤2.2 million from Austria-Hungary.[69]

Austria-Hungary began releasing secret documents in which Russia, since 1878, had repeatedly stated that Austria-Hungary had a free hand in Bosnia-Herzegovina and the Sanjak of Novibazar. At the same time, Germany stated it would only continue its active involvement in negotiations if Russia accepted the annexation. Under these pressures, Russia agreed to the annexation,[70] and persuaded Serbia to do the same. The Treaty of Berlin then was amended by correspondence between capitals from 7 April to 19 April 1909, to reflect the annexation.

The Balkan Wars (1912–13)

The Balkan Wars in 1912–1913 increased international tension between the Russian Empire and Austria-Hungary. It also led to a strengthening of Serbia and a weakening of the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria, who might otherwise have kept Serbia under control, thus disrupting the balance of power in Europe in favor of Russia.

Russia initially agreed to avoid territorial changes, but later in 1912 supported Serbia's demand for an Albanian port. An international conference was held in London in 1912–1913 where it was agreed to create an independent Albania, however both Serbia and Montenegro refused to comply. After an Austrian, and then an international naval demonstration in early 1912 and Russia's withdrawal of support Serbia backed down. Montenegro was not as compliant and on May 2, the Austrian council of ministers met and decided to give Montenegro a last chance to comply and, if it would not, then to resort to military action. However, seeing the Austrian military preparations, the Montenegrins requested the ultimatum be delayed and complied.[71]

The Serbian government, having failed to get Albania, now demanded that the other spoils of the First Balkan War be reapportioned and Russia failed to pressure Serbia to back down. Serbia and Greece allied against Bulgaria, which responded with a preemptive strike against their forces beginning the Second Balkan War.[72] The Bulgarian army crumbled quickly when Turkey and Romania joined the war.

The Balkan Wars strained the German/Austro-Hungarian alliance. The attitude of the German government to Austrian requests of support against Serbia was initially both divided and inconsistent. After the German Imperial War Council of 8 December 1912, it was clear that Germany was not ready to support Austria-Hungary in a war against Serbia and her likely allies.

In addition, German diplomacy before, during, and after the Second Balkan War was pro-Greek and pro-Romanian and in opposition to Austria-Hungary's increasingly pro-Bulgarian views. The result was tremendous damage to Austro-German relations. Austrian foreign minister Leopold von Berchtold remarked to German ambassador Heinrich von Tschirschky in July 1913 that "Austria-Hungary might as well belong 'to the other grouping' for all the good Berlin had been".[73]

In September 1913, it was learned that Serbia was moving into Albania and Russia was doing nothing to restrain it, while the Serbian government would not guarantee to respect Albania's territorial integrity and suggested there would be some frontier modifications. In October 1913, the council of ministers decided to send Serbia a warning followed by an ultimatum: that Germany and Italy be notified of some action and asked for support, and that spies be sent to report if there was an actual withdrawal. Serbia responded to the warning with defiance and the Ultimatum was dispatched on October 17 and received the following day. It demanded that Serbia evacuate Albanian territory within eight days. Serbia complied, and the Kaiser made a congratulatory visit to Vienna to try to fix some of the damage done earlier in the year.[74]

The conflicts demonstrated that a localized war in the Balkans could alter the balance of power without provoking general war and reinforced the attitude in the Austrian government. This attitude had been developing since the Bosnian annexation crisis that ultimatums were the only effective means of influencing Serbia and that Russia would not back its refusal with force. They also dealt catastrophic damage to the Habsburg economy.

Historiography

During the period immediately following the end of hostilities, Anglo-American historians argued that Germany was solely responsible for the start of the war. However, academic work in the English-speaking world in the later 1920s and 1930s blamed participants more equally.

Since the 1960s, the tendency has been to reassert the guilt of Germany, although some historians continue to argue for collective responsibility.

Discussion over which country "started" the war, and who bears the blame continues to this day.[75]

See also

- American entry into World War I

- Causes of World War II

- European Civil War

- History of the Balkans

- International relations (1814–1919)

References

- ↑ Henig (2002). The origins of the First World War. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-26205-4.

- ↑ Lieven, D. C. B. (1983). Russia and the origins of the First World War. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-69608-6.

- ↑ Van Evera, Stephen. "The Cult of the Offensive and the Origins of the First World War." (Summer 1984), p. 62.

- ↑ Fischer, Fritz. "War of Illusions: German Policies from 1911 to 1914." trans. (1975), p. 69.

- ↑ Sagan, Scott D. 1914 Revisited: Allies, Offense, and Instability (1986)

- ↑ William Mulligan, "The Trial Continues: New Directions in the Study of the Origins of the First World War." English Historical Review (2014) 129#538 pp: 639-666 at p 641.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 7.9 7.10 7.11 7.12 Fromkin, David. Europe's last summer: who started the Great War in 1914?. New York : Knopf : 2004. pp. 88–92. ISBN 978-0-375-41156-4.

- ↑ The Kaiser and His Court: Wilhelm II and the Government of Germany by John C. G. Röhl; Translated by Terence F. Cole, Cambridge University Press; 288 pages. p. 257.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 9.8 9.9 9.10 Röhl, John C G. 1914: Delusion or Design. Elek. pp. 29–32. ISBN 0-236-15466-4.

- ↑ Fromkin, David. Europe's last summer: who started the Great War in 1914?. New York : Knopf : 2004. pp. 260–62. ISBN 978-0-375-41156-4.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Fromkin, David. Europe's last summer: who started the Great War in 1914?. New York : Knopf : 2004. pp. 80–82. ISBN 978-0-375-41156-4.

- ↑ Howard, Michael "Europe on the Eve of the First World War" pages 21–34 from The Outbreak of World War I edited by Holger Herwig, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1997 page 26

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 Fromkin, David. Europe's last summer: who started the Great War in 1914?. New York : Knopf : 2004. pp. 124–25. ISBN 978-0-375-41156-4.

- ↑ Dedijer, Vladimir. The Road to Sarajevo, Simon and Schuster, New York, 1966, p 398

- ↑

- Fischer, Fritz Germany's Aims in the First World War, W. W. Norton; 1967 ISBN 0-393-05347-4

- ↑ I.Hull, ‘The Entourage of Kaiser Wilhelm II’ p259; M.Neiberg, ‘The World War 1 Reader’ p309

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Ferguson, Niall The Pity of War Basic Books, 1999 ISBN 0-465-05712-8

- ↑ Christopher Clark, The Sleepwalkers (2013) pp 132–6, 190–97, 301-13498-506

- ↑ Wank, Soloman (1997). "The Habsburg Empire". In Karen Barkey and Mark von Hagen. After Empire: Multiethnic Societies and Nation-Building. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Garland, John (1997). "The Strength of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy in 1914 (Part 1)". New Perspective. Retrieved May 15, 2010.

- ↑ Williamson, Samuel R. (1991). Austria-Hungary and the Origins of the First World War. St. Martin's Press. p. 15. ISBN 0-312-05239-1.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Leslie, John (1993). Elisabeth Springer and Leopold Kammerhofer, ed. "The Antecedents of Austria-Hungary's War Aims". Wiener Beiträge zur Geschichte der Neuzeit 20: 307–394.

- ↑ Sked, Alan (1989). The Decline and Fall of the Habsburg Empire 1815–1918. Burnt Mill: Longman Group. p. 254.

- ↑ Williamson, Samuel R. (1991). Austria-Hungary and the Origins of the First World War. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-05239-1.

- ↑ William Mulligan (2010). The Origins of the First World War. Cambridge UP. p. 7.

- ↑ John Darwin, Unfinished Empire: The Global Expansion of Britain, (2012) p 388.

- ↑ See: Turkish Petroleum Company

- ↑ Jastrow, p.150, p.160

- ↑ Sean McMeekin, 'The Berlin-Baghdad Express: The Ottoman Empire and Germany's bid for world power. 2010, ISBN 978-0-674-05739-5

- ↑ "Jastrow, 1917. page 97 in 'The War and the Baghdad Railway'". Archive.org. Retrieved 2013-10-28.

- ↑ "AF Pollard, 1919. 'A Short History of the Great War' accessible at" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-10-28.

- ↑ "Kuwait". State.gov. 2012-10-24. Retrieved 2013-10-28.

- ↑ Greg Cashman; Leonard C. Robinson (2007). An Introduction to the Causes of War: Patterns of Interstate Conflict from World War I to Iraq. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 71.

- ↑ FO 373/5/2, p.33.

- ↑ Bilgin. p 127-8. http://dergiler.ankara.edu.tr/dergiler/19/1273/14662.pdf

- ↑ Christopher Clark, The Sleepwalkers (2013) p 338

- ↑ William L. Langer, et al. Western Civilization (1968), p. 528

- ↑ C. L. Mowat, ed., The New Cambridge Modern History, Vol. 12: The Shifting Balance of World Forces, 1898-1945 (1968) pp 151-52

- ↑ Weikart, Richard (2004). From Darwin to Hitler: Evolutionary ethics, Eugenics and Racism in Germany. ISBN 1-4039-6502-1.

- ↑ Hamilton, Richard F.; Herwig, Holger H. (2003). The Origins of World War I. Cambridge University Press. p. 26.

- ↑ Leslie, JD (1993). "The Antecedents of Austria-Hungary's War Aims". In E Springer and L Kammerhofer. Archiv und Forschung das Haus-, Hof- und Staats-Archiv in Seiner Bedeutung für die Geschichte Österreichs und Europas. R. Oldenburg, Munich. pp. 307–394.

- ↑ H E Legge, How War Came About Between Great Britain and Germany

- ↑ Albertini, Luigi. Origins of the War of 1914, Oxford University Press, London, 1953, Vol II pp 461–462, 465

- ↑ The Treaty of Alliance Between Germany and Turkey August 2, 1914

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Taylor, A. J. P. (1954). The Struggle For Mastery in Europe 1848–1918. Oxford University Press. p. 524. ISBN 0-19-881270-1.

- ↑ F. H. Hinsley, ed. The New Cambridge Modern History, Vol. 11: Material Progress and World-Wide Problems, 1870–98 (1962) pp 204–42, esp 214-17

- ↑ Mulligan, "The Trial Continues" (2014) pp 643-49

- ↑ Ferguson 1999, p. 82.

- ↑ Mulligan, "The Trial Continues" (2014) pp 646-47

- ↑ Angus Ross, "HMS Dreadnought (1906)—A Naval Revolution Misinterpreted or Mishandled?" The Northern Mariner (April 2010) 20#2 pp: 175-198

- ↑ Robert J. Blyth et al. eds. The Dreadnought and the Edwardian Age (2011)

- ↑ Ferguson 1999, pp. 83–85.

- ↑ Lambert, Nicholas A. "British Naval Policy, 1913–1914: Financial Limitation and Strategic Revolution" The Journal of Modern History, 67, no.3 (1995), pages 623–626.

- ↑ Barbara Jelavich. Russia's Balkan Entanglements, 1806–1914 (2004) p 10

- ↑ Sean McMeekin, The Russian Origins of the First World War (Harvard University Press, 2011).

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 56.2 Tuchman, Barbara (1962). The Guns of August. New York: Random House. pp. 158–159.

- ↑ Kolbert, Elizabeth (2013-10-21). "Head Count". The New Yorker. Retrieved 14 October 2013.

- ↑ Taylor, A. J. P. "War by Timetable: How the First World War Began" (London, 1969)

- ↑ Trachtenberg, Marc "The Meaning of Mobilization in 1914" International Security Vol. 15, No. 3 (1990–1991), 141.

- ↑ Stevenson, David "War by Timetable? The Railway Race before 1914" Past and Present, 162 (1999), 192. Also see Williamson Samuel R. Jr. and Ernest R. May "An Identity of Opinion: Historians and July 1914" The Journal of Modern History 79, (June 2007), 361–362, or Trachtenberg, Marc "The Meaning of Mobilization in 1914" International Security Vol. 15, No. 3 (1990–1991), 140–141.

- ↑ Tuchman, Barbara (1989) [1962]. The Guns of August. New York: Macmillan. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-02-620311-1.

- ↑ Zuber 2010, pp. 95–97, 116–133.

- ↑ Zuber 2010, pp. 116–131.

- ↑ Holmes 2014, pp. 194, 211.

- ↑ Holmes 2014, p. 213.

- ↑ Kennedy, Paul The Rise of the Anglo-German Antagonism, 1860–1914, Allen & Unwin, 1980 ISBN 0-04-940060-6, pp 457–62.

- ↑ Paul M. Kennedy, The Rise of the Anglo-German Antagonism, 1860–1914 (1980) pp 464–70

- ↑ Albertini, Luigi. Origins of the War of 1914, Enigma Books, New York, 2005, Vol I, p 218–219

- ↑ Albertini, Luigi. Origins of the War of 1914, Enigma Books, New York, 2005, Vol I, p 277

- ↑ Albertini, Luigi. Origins of the War of 1914, Enigma Books, New York, 2005, Vol I, p 287

- ↑ Williamson, Samuel R. Jr., Austria-Hungary and the Origins of the First World War, 125–140.

- ↑ Williamson, Samuel R. Jr., Austria-Hungary and the Origins of the First World War, 143–145.

- ↑ Williamson, Samuel R. Jr., Austria-Hungary and the Origins of the First World War, 147–149.

- ↑ Williamson, Samuel R. Jr., Austria-Hungary and the Origins of the First World War, 151–154.

- ↑ "World War One: 10 interpretations of who started WW1". BBC News. 12 February 2014. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

Further reading

- Albertini, Luigi. The Origins of the War of 1914, trans. Isabella M. Massey, 3 vols., London, Oxford University Press, 1952 OCLC 168712

- Barnes, Harry Elmer. In Quest of Truth And Justice: De-bunking The War Guilt Myth, New York: Arno Press, 1972, 1928 ISBN 0-405-00414-1 OCLC 364103

- Carter, Miranda Three Emperors: Three Cousins, Three Empires and the Road to the First World War. London, Penguin, 2009. ISBN 978-0-670-91556-9

- Clark, Christopher. The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914 (2012) excerpt and text search

- Evans, R. J. W. and Hartmut Pogge von Strandman, eds. The Coming of the First World War (1990), essays by scholars from both sides ISBN 0-19-822899-6

- Evera, Stephen Van, "The Cult of the Offensive and the Origins of the First World War," in International Security 9 #1 (1984)

- Fay, Sidney, The Origins of the World War, New York: Macmillan, 1929, 1928 OCLC 47080822.

- Ferguson, Niall The Pity of War Basic Books, 1999 ISBN 0-465-05712-8

- Fischer, Fritz, Germany's Aims In the First World War, W. W. Norton; 1967 ISBN 0-393-05347-4

- Fischer, Fritz, War of Illusions:German policies from 1911 to 1914 Norton, 1975 ISBN 0-393-05480-2

- Fromkin, David, Europe's Last Summer: Who Started The Great War in 1914?, Knopf 2004 ISBN 0-375-41156-9

- Gilpin, Robert, War and Change in World Politics Cambridge University Press, 1981 ISBN 0-521-24018-2

- Hamilton, Richard and Herwig, Holger, Decisions for War, 1914–1917 Cambridge University Press, 2004 ISBN 0-521-83679-4

- Henig, Ruth, The Origins of the First World War (2002) ISBN 0-415-26205-4

- Herrmann, David G., The Arming of Europe and the Making of the First World War (1997). Princeton Studies in International History and Politics, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0691015958

- Hillgruber, Andreas Germany and the Two World Wars, Harvard University Press, 1981 ISBN 0-674-35321-8

- Hobson, Rolf, Imperialism at Sea: Naval Strategic Thought, the Ideology of Sea Power, and the Tirpitz Plan (2002) ISBN 0-391-04105-3

- Joll, James, The Origins of the First World War (1984) ISBN 0-582-49016-2

- Keiger, John F. V., France and the Origins of the First World War, St. Martin's Press, 1983 ISBN 0-312-30292-4

- Kennedy, Paul, The Rise of the Anglo-German Antagonism, 1860–1914, Allen & Unwin, 1980 ISBN 0-04-940060-6.

- Kennedy, Paul M. (ed.), The War Plans of the Great Powers, 1880–1914. (1979) ISBN 0-04-940056-8

- Knutsen, Torbjørn L., The Rise and Fall of World Orders Manchester University Press, 1999 ISBN 0-7190-4057-4

- Kuliabin A. Semin S.Russia – a counterbalancing agent to the Asia. "Zavtra Rossii", #28, 17 July 1997

- Lee, Dwight E. ed. The Outbreak of the First World War: Who Was Responsible? (1958) OCLC 66082903, readings from, multiple points of view

- Lenin, Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism Progress Publishers, Moscow, (1978) OCLC 14695433

- Leslie, John, The Antecedents of Austria-Hungary's War Aims, (Wiener Beiträge zur Geschichte der Neuzeit) Elisabeth Springer and Leopold Kammerhofer (eds.), 20 (1993): 307–394.

- Lieven, D. C. B Russia and the Origins of the First World War, St. Martin's Press, 1983 ISBN 0-312-69608-6

- Lowe, C. J. and Michael L. Dockrill, Mirage of Power: 1902–14 v. 1: British Foreign Policy (1972); Mirage of Power: 1914–22 v. 2: British Foreign Policy (1972); Mirage of Power: The Documents v. 3: British Foreign Policy (1972); vol 1–2 are text, vol 3 = primary sources

- Lynn-Jones, Sean M., and Stephen Van Evera (eds.), Military Strategy and the Origins of the First World War (2nd ed., Princeton UP, 1991) ISBN 0-691-02349-2

- MacMillan, Margaret, The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914 (Random House, 2013) ISBN 1-400-06855-X OCLC 833381194

- McMeekin, Sean, The Russian Origins of the First World War (Harvard University Press, 2011) ISBN 0-674-06210-8 OCLC 709670289

- Mayer, Arno The Persistence of the Old Regime: Europe to the Great War Croom Helm, 1981 ISBN 0-394-51141-7

- Neiberg, Michael S. Dance of the Furies: Europe and the Outbreak of World War I (Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2011) ISBN 0-674-04954-3 OCLC 676725362; role of public opinion

- Ponting, Clive, Thirteen Days. (Chatto & Windus, 2002) ISBN 0-701-17293-2 OCLC 49872036

- Remak, Joachim, The Origins of World War I, 1871–1914, 1967 ISBN 0-03-082839-2

- Snyder, Jack, "Civil—Military Relations and the Cult of the Offensive, 1914 and 1984," International Security 9 No. 1 (1984)

- Steiner, Zara, Britain and the Origins of the First World War Macmillan Press, 1977 ISBN 0-312-09818-9

- Stevenson, David, Cataclysm: The First World War As Political Tragedy (2004) major reinterpretation ISBN 0-465-08184-3

- Stevenson, David, The First World War and International Politics (Oxford University Press, 1998)ISBN 0-198-20281-4 OCLC 16833256

- Strachan, Hew. The First World War: Volume I: To Arms (2004): the major scholarly synthesis. Thorough coverage of 1914; Also: The First World War (2004) ISBN 0-670-03295-6 OCLC 53075929: a 385pp version of his multivolume history

- Taylor, A. J. P., War by Time-Table: How The First World War Began, Macdonald & Co., 1969 ISBN 0-356-04206-5

- Tuchman, Barbara, The Guns of August, New York. The Macmillan Company, 1962. Heavily reprinted since 1962. ISBN 0-553-13959-2 OCLC 16673067Describes the opening diplomatic and military manoeuvres.

- Tucker, Spencer, ed., European Powers in the First World War: An Encyclopedia (1999) ISBN 0-815-33351-X OCLC 40417794

- Turner, L. C. F. Origins of the First World War, New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1970. ISBN 0-393-09947-4

- Wehler, Hans-Ulrich The German Empire, 1871–1918, Berg Publishers, 1985 ISBN 0-907582-22-2

- Williamson, Samuel R. Austria-Hungary and the Origins of the First World War, St. Martin's Press, 1991 ISBN 0-312-05239-1

Historiography

- Cohen, Warren I. American Revisionists: The Lessons of Intervention in World War One (1967) OCLC 466464

- D'Agostino, Anthony. "The Revisionist Tradition in European Diplomatic History," Journal of the Historical Society, (Spring 2004) 4#2 pp: 255–287 doi:10.1111/j.1529-921X.2004.00098.x

- Gillette, Aaron. "Why Did They Fight the Great War? A Multi-Level Class Analysis of the Causes of the First World War," History Teacher, (2006) 40#1 pp 45–58 in JSTOR

- Hewitson, Mark. Germany and the causes of the First World War (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2014)

- Iriye, Akira. "The Historiographic Impact of the Great War." Diplomatic History (Sept. 2014) 38#4 online

- Jones, Heather. "As the Centenary Approaches: The Regeneration of First World War Historiography," Historical Journal (2013) 56#4 pp: pp 857–878 doi:10.1017/S0018246X13000216

- Keiger, J. F. V. "The Fischer Controversy, the War Origins Debate and France: A Non-History." Journal of Contemporary History (2013) 48#2 pp 363–375. DOI: 10.1177/0022009412472715

- Kramer, Alan. "Recent Historiography of the First World War-Part I." Journal of Modern European History (2014) 12#1 pp: 5-27. online; "Recent Historiography of the First World War (Part II)." ibid. (2014) 12#2 pp: 155-174. online

- Marczewski, Jerzy. "German Historiography and the Problem of Germany's Responsibility for World War I," Polish Western Affairs, (1977) 12#2 pp 289–309

- Mombauer, Annika. "The First World War: Inevitable, Avoidable, Improbable Or Desirable? Recent Interpretations On War Guilt and the War's Origins," German History, (2007) 25#1 pp 78–95, online

- Mulligan, William. "The Trial Continues: New Directions in the Study of the Origins of the First World War." English Historical Review (2014) 129#538 pp: 639-666 online

- Nugent, Christine. "The Fischer Controversy: Historiographical Revolution or Just Another Historians' Quarrel?," Journal of the North Carolina Association of Historians, (April 2008), Vol. 16, pp 77–114

- Ritter, Gerhard "Anti-Fischer: A New War-Guilt Thesis?" pages 135–142 from The Outbreak of World War One: Causes and Responsibilities, edited by Holger Herwig, 1997; originally published 1962

- Schroeder, Paul W. (2000) Embedded Counterfactuals and World War I as an Unavoidable War (PDF file)

- Seipp, Adam R. "Beyond the 'Seminal Catastrophe': Re-imagining the First World War," Journal of Contemporary History, October 2006, Vol. 41 Issue 4, pp 757–766 in JSTOR

- Showalter, Dennis. "The Great War and Its Historiography," Historian, Winter 2006, Vol. 68 Issue 4, pp 713–721 online

- Smith, Leonard V. "The 'Culture De Guerre' and French Historiography of the Great War of 1914–1918," History Compass, (November 2007) 5#6 pp 1967–1979 online

- Strachan, Hew. "The origins of the First World War." International Affairs (2014) 90#2 pp: 429-439. online

- Waite, Robert G. "The dangerous and menacing war psychology of hatred and myth". American Historians and the Outbreak of the First World War 1914. An Overview." Berliner Gesellschaft für Faschismus und Weltkriegsforschung (2014): 1-15.

- Williamson, Jr., Samuel R. and Ernest R. May. "An Identity of Opinion: Historians and July 1914," Journal of Modern History, June 2007, Vol. 79 Issue 2, pp 335–387 in JSTOR comprehensive historiography

Primary sources

- French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, The French Yellow Book: Diplomatic Documents (1914)

- Reichstag speeches,

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to World War I origins. |

- Overview of Causes and Primary Sources

- Russia – Getting Too Strong for Germany by Norman Stone

- The Origins of World War One: An article by Dr. Gary Sheffield at the BBC History site.

- What caused World War I: Timeline of events and origins of WWI

- Kuliabin A. Semine S. Some of aspects of state national economy evolution in the system of the international economic order.- USSR ACADEMY OF SCIENCES FAR EAST DIVISION INSTITUTE FOR ECONOMIC & INTERNATIONAL OCEAN STUDIES Vladivostok, 1991

- The Evidence in the Case: A Discussion of the Moral Responsibility for the War of 1914, as Disclosed by the Diplomatic Records of England, Germany, Russia by James M. Beck

- Concept Map of the Causes of WWI

- 'World War One and 100 Years of Counter-Revolution' by Mark Kosman (on the domestic causes of war)