Cauchy product

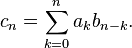

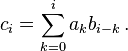

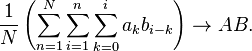

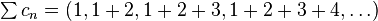

In mathematics, the Cauchy product, named after Augustin Louis Cauchy, of two sequences  ,

,  , is the discrete convolution of the two sequences, the sequence

, is the discrete convolution of the two sequences, the sequence  whose general term is given by

whose general term is given by

In other words, it is the sequence whose associated formal power series  is the product of the two series similarly associated to

is the product of the two series similarly associated to  and

and  .

.

Series

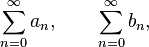

A particularly important example is to consider the sequences  to be terms of two strictly formal (not necessarily convergent) series

to be terms of two strictly formal (not necessarily convergent) series

usually, of real or complex numbers. Then the Cauchy product is defined by a discrete convolution as follows.

for n = 0, 1, 2, ...

"Formal" means we are manipulating series in disregard of any questions of convergence. These need not be convergent series. See in particular formal power series.

One hopes, by analogy with finite sums, that in cases in which the two series do actually converge, the sum of the infinite series

is equal to the product

just as would work when each of the two sums being multiplied has only finitely many terms. This is not true in general, but see Mertens' Theorem and Cesàro's theorem below for some special cases.

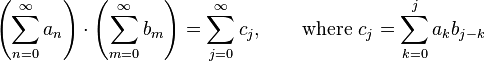

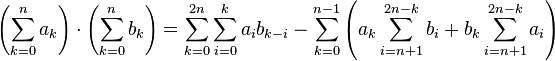

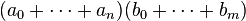

Finite summations

The product of two finite series ak and bk with k between 0 and n satisfies the equation:

Convergence and Mertens' theorem

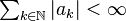

Let (an)n≥0 and (bn)n≥0 be real or complex sequences. It was proved by Franz Mertens that, if the series  converges to A and

converges to A and  converges to B, and at least one of them converges absolutely, then their Cauchy product converges to AB.

converges to B, and at least one of them converges absolutely, then their Cauchy product converges to AB.

It is not sufficient for both series to be convergent; if both sequences are conditionally convergent, the Cauchy product does not have to converge towards the product of the two series, as the following example shows:

Example

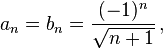

Consider the two alternating series with

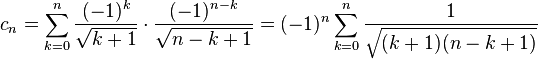

which are only conditionally convergent (the divergence of the series of the absolute values follows from the direct comparison test and the divergence of the harmonic series). The terms of their Cauchy product are given by

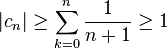

for every integer n ≥ 0. Since for every k ∈ {0, 1, ..., n} we have the inequalities k + 1 ≤ n + 1 and n – k + 1 ≤ n + 1, it follows for the square root in the denominator that √(k + 1)(n − k + 1) ≤ n +1, hence, because there are n + 1 summands,

for every integer n ≥ 0. Therefore, cn does not converge to zero as n → ∞, hence the series of the (cn)n≥0 diverges by the term test.

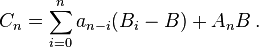

Proof of Mertens' theorem

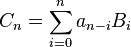

Assume without loss of generality that the series of the  converges absolutely.

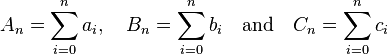

Define the partial sums

converges absolutely.

Define the partial sums

with

Then

by rearrangement, hence

-

(1)

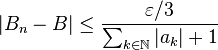

Fix ε > 0. Since  by absolute convergence, and since Bn converges to B as n → ∞, there exists an integer N such that, for all integers n ≥ N,

by absolute convergence, and since Bn converges to B as n → ∞, there exists an integer N such that, for all integers n ≥ N,

-

(2)

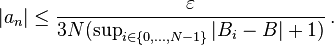

(this is the only place where the absolute convergence is used). Since the series of the (an)n≥0 converges, the individual an must converge to 0 by the term test. Hence there exists an integer M such that, for all integers n ≥ M,

-

(3)

Also, since An converges to A as n → ∞, there exists an integer L such that, for all integers n ≥ L,

-

(4)

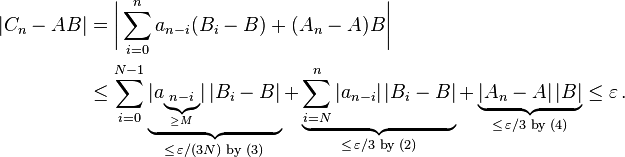

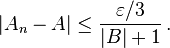

Then, for all integers n ≥ max{L, M + N}, use the representation (1) for Cn, split the sum in two parts, use the triangle inequality for the absolute value, and finally use the three estimates (2), (3) and (4) to show that

By the definition of convergence of a series, Cn → AB as required.

Examples

Finite series

Suppose  for all

for all  and

and  for all

for all  . Here the Cauchy product of

. Here the Cauchy product of  and

and  is readily verified to be

is readily verified to be  . Therefore, for finite series (which are finite sums), Cauchy multiplication is direct multiplication of those series.

. Therefore, for finite series (which are finite sums), Cauchy multiplication is direct multiplication of those series.

Infinite series

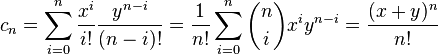

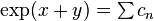

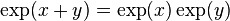

- For some

, let

, let  and

and  . Then

. Then

by definition and the binomial formula. Since, formally,  and

and  , we have shown that

, we have shown that  . Since the limit of the Cauchy product of two absolutely convergent series is equal to the product of the limits of those series, we have proven the formula

. Since the limit of the Cauchy product of two absolutely convergent series is equal to the product of the limits of those series, we have proven the formula  for all

for all  .

.

- As a second example, let

for all

for all  . Then

. Then  for all

for all  so the Cauchy product

so the Cauchy product  does not converge.

does not converge.

Cesàro's theorem

In cases where the two sequences are convergent but not absolutely convergent, the Cauchy product is still Cesàro summable. Specifically:

If  ,

,  are real sequences with

are real sequences with  and

and  then

then

This can be generalised to the case where the two sequences are not convergent but just Cesàro summable:

Theorem

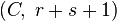

For  and

and  , suppose the sequence

, suppose the sequence  is

is  summable with sum A and

summable with sum A and  is

is  summable with sum B. Then their Cauchy product is

summable with sum B. Then their Cauchy product is  summable with sum AB.

summable with sum AB.

Generalizations

All of the foregoing applies to sequences in  (complex numbers). The Cauchy product can be defined for series in the

(complex numbers). The Cauchy product can be defined for series in the  spaces (Euclidean spaces) where multiplication is the inner product. In this case, we have the result that if two series converge absolutely then their Cauchy product converges absolutely to the inner product of the limits.

spaces (Euclidean spaces) where multiplication is the inner product. In this case, we have the result that if two series converge absolutely then their Cauchy product converges absolutely to the inner product of the limits.

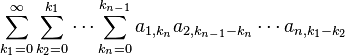

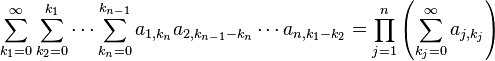

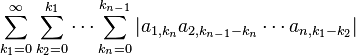

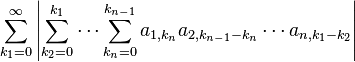

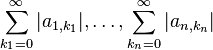

Products of finitely many infinite series

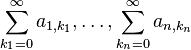

Let  such that

such that  (actually the following is also true for

(actually the following is also true for  but the statement becomes trivial in that case) and let

but the statement becomes trivial in that case) and let  be infinite series with complex coefficients, from which all except the

be infinite series with complex coefficients, from which all except the  th one converge absolutely, and the

th one converge absolutely, and the  th one converges. Then the series

th one converges. Then the series

converges and we have:

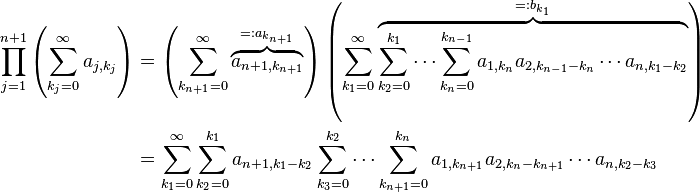

This statement can be proven by induction over  : The case for

: The case for  is identical to the claim about the Cauchy product. This is our induction base.

is identical to the claim about the Cauchy product. This is our induction base.

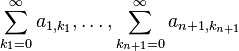

The induction step goes as follows: Let the claim be true for an  such that

such that  , and let

, and let  be infinite series with complex coefficients, from which all except the

be infinite series with complex coefficients, from which all except the  th one converge absolutely, and the

th one converge absolutely, and the  th one converges. We first apply the induction hypothesis to the series

th one converges. We first apply the induction hypothesis to the series  . We obtain that the series

. We obtain that the series

converges, and hence, by the triangle inequality and the sandwich criterion, the series

converges, and hence the series

converges absolutely. Therefore, by the induction hypothesis, by what Mertens proved, and by renaming of variables, we have:

Therefore, the formula also holds for  .

.

Relation to convolution of functions

One can also define the Cauchy product of doubly infinite sequences, thought of as functions on  . In this case the Cauchy product is not always defined: for instance, the Cauchy product of the constant sequence 1 with itself,

. In this case the Cauchy product is not always defined: for instance, the Cauchy product of the constant sequence 1 with itself,  is not defined. This doesn't arise for singly infinite sequences, as these have only finite sums.

is not defined. This doesn't arise for singly infinite sequences, as these have only finite sums.

One has some pairings, for instance the product of a finite sequence with any sequence, and the product  .

This is related to duality of Lp spaces.

.

This is related to duality of Lp spaces.

References

- Apostol, Tom M. (1974), Mathematical Analysis (2nd ed.), Addison Wesley, p. 204, ISBN 978-0-201-00288-1

- Hardy, G. H. (1949), Divergent Series, Oxford University Press, p. 227–229