Catholic League (German)

| Catholic League Katholische Liga | |

.svg.png) | |

| Defence Confederation of Catholic States | |

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Members |

|

| Adversary | Protestant Union

|

| President | Duke of Bavaria (Maximilian I, 1609–35) Archbishop-Elector of Mainz (Johann Schweikhard von Kronberg, 1609–26; Georg Friedrich von Greiffenklau, 1626–29; Anselm Casimir Wambold von Umstadt, 1629–35) |

| Commander |

|

| Formation | July 10, 1609: Diet of Munich |

| Collapse | May 30, 1635: Peace of Prague |

The German Catholic League (German: Katholische Liga) was initially a loose confederation of Roman Catholic German states formed on July 10, 1609 to counteract the Protestant Union (formed 1608), whereby the participating states concluded an alliance "for the defence of the Catholic religion and peace within the Empire." Modelled loosely on the more intransigent ultra-Catholic French Catholic League (1576), the German Catholic league initially acted politically to negotiate issues with the slightly older Protestant Union.

Nevertheless, the league's founding, as had the founding of the Protestant Union, further exacerbated long standing tensions between the Protestant reformers and the members of the Catholic Church which thereafter began to get worse with ever more frequent episodes of civil disobedience, repression, and retaliations that would eventually ignite into the first phase of the Thirty Years' War roughly a decade later with the act of rebellion and calculated insult known as the Second Defenestration of Prague on 23 May 1618.

Background

In 1555, the Peace of Augsburg was signed, which confirmed the result of the Diet of Speyer (1526) and ended the violence between the Lutherans and the Catholics in Germany.

It stated that:

- German princes (numbering 225) could choose the religion (Lutheranism or Catholicism) for their realms according to their conscience (the principle of cuius regio, eius religio).

- Lutherans living in an ecclesiastical state (under the control of a Catholic prince-bishop) could remain Lutherans.

- Lutherans could keep the territory that they had captured from the Catholic Church since the Peace of Passau (1552).

- The ecclesiastical leaders of the Catholic Church (bishops) that converted to Lutheranism had to give up their territory (the principle called reservatum ecclesiasticum).

Those occupying a state that had officially chosen either Lutheranism or Catholicism could not practice the religion differing to that of the state.

Although the Peace created a temporary end to hostilities, the underlying bases of the religious conflict remained unsolved. Both parties interpreted it at their convenience, the Lutherans in particular considering it only a momentary agreement. Further, Calvinism spread quickly throughout Germany, adding a third major Christian worldview to the region, but its position was not supported in any way by the Augsburg terms, since Catholicism and Lutheranism were the only permitted creeds.

The foundation of the Catholic League

The best documented reason of the foundation of the Catholic League was an incident in the town of Donauwörth, a Free Imperial City within the territory of Bavaria. On April 25, 1606, the Lutheran majority of the town barred the Catholic residents of the town from holding an annual Markus procession, to show the rule of their confession over the town. The Catholics, led by five monks, wanted to pass through the town and on to the nearby village of Ausesheim, showing their flags and singing hymns. They were permitted to do so by the terms of the Peace of Augsburg. The city council would only allow them to re-enter town without flags and singing. The conflict ended in a brawl.

On protest of the bishop of Augsburg, Catholic Emperor Rudolf II of Habsburg threatened an Imperial ban in case of further violation of the rights of the Catholic citizens. Nevertheless, next year similar anti-Catholic incidents of civil disobedience took place, and the participants of the Markus procession were thrown out of town.

Emperor Rudolf then declared an Imperial ban on the town and ordered Maximilian I, Duke of Bavaria to execute the ban. Facing his army, the town surrendered. According to Imperial law, the disciplinary measures should not have been executed by the Catholic duke of Bavaria, but by the Protestant duke of Württemberg, who, like Donauwörth, was a member of the Swabian Imperial Circle. Maximilian de facto absorbed the former Free Imperial City, which was a violation of Imperial law as well.

In the same year, the Catholic majority of the Reichstag meeting in the Diet of Augsburg resolved that the renewal of the Peace of Augsburg of 1555 should be conditional on the restoration of all church land appropriated since 1552. Acting on these events, the Protestant princes formed a military alliance on May 14, 1608, the Protestant Union, whose leader was Frederick IV of Wittelsbach, the Elector Palatine.

To create a union of Catholic states as a counterpart to this Protestant Union, early in 1608 Maximilian started negotiations with other Catholic princes.[1] On July 5, 1608, the spiritual electors manifested a tendency in favour of the confederacy suggested by Maximilian. Opinions were even expressed as to the size of the confederate military forces to be raised.

In July 1609, the representatives of the Prince-Bishops of Augsburg, Constance, Passau, Regensburg, and Würzburg assembled at Munich. The Prince-Archbishop of Salzburg, having shown disapproval, was not invited, and the Prince-Bishop of Eichstädt hesitated. On July 10, 1609, the participating states concluded an alliance "for the defence of the Catholic religion and peace within the Empire." The most important regulation of the League was the prohibition of attacks on one another. Instead of fighting, conflicts had to be decided by the laws of the Empire or, if these failed to solve the conflict, by arbitration within the League. Should one member be attacked, it had to be helped with military or alternatively legal support. Duke Maximilian was to be the president, and the Prince-Bishops of Augsburg, Passau, and Würzburg his councillors. The League was to continue for nine years.

The Munich Diet failed to erect a substantial structure for the newly formed League. On June 18, 1609, the Electors of Mainz, Cologne, and Trier had proposed an army of 20,000 men. They had also considered making Maximilian president of the alliance, and on August 30 they announced their adhesion to the Munich agreement, provided that Maximilian accepted the Elector of Mainz, arch-chancellor of the Empire, as co-president.

To create a structure, several general meetings of the members were arranged. On February 10, 1610, the representatives of all the important Catholic states, except for Austria and Salzburg — and a great number of the smaller ones — met at Würzburg to decide the organization, funding and arming of the League. This was the real beginning of the Catholic League. The Pope, the Emperor and the King of Spain, who had been informed by Maximilian, were all favorably disposed towards the undertaking.

The main problem of the League was the unreadiness of its members. In April 1610, the contributions of all its members were not yet paid; Maximilian threatened to resign. To prevent him from doing so, Spain, which had made the giving of a subsidy dependent on Austria's enrollment in the League, waived this condition, and the pope promised a further contribution.

The conduct of the Union in the Jülich dispute and the warlike operations of the Union army in Alsace seemed to make a battle between League and Union inevitable.

In the year 1613 at Regensburg, Austria joined the League. The assembly now appointed no less than three war-directors: Duke Maximilian, and Archdukes Albert and Maximilian of Austria. The object of the League was now declared "a Christian legal defense" The membership of Austria made the League part of the struggles between the emperor and his Protestant vassals in Bohemia and Lower Austria, that would lead to the beginning of the Thirty Years' War.

Duke Maximilian refused to accept the resolutions of Ratisbon and even resigned the post as president, when Archduke Maximilian III of Austria, the Prince Elector of Mainz and the Prince Elector of Trier, protested the inclusion of the Bishop of Augsburg, and the Provost of Ellwangen in the Bavarian Directory. On May 27, 1617, with the Prince-Bishops of Bamberg, Eichstädt, Würzburg, and the Prince-Provost of Ellwangen, Bavaria formed a separate league for nine years.

At the end of 1618, the position of the Emperor in Bohemia as in Lower and Upper Austria gradually became critical. Searching for help, the Emperor tried to restore the League. A meeting of several of the ecclesiastical Princes decided to reconstruct the League on its original basis. It would consist of two groups: the Rhenish district under the presidency of Mainz, and the Oberland district, presided by Bavaria; the treasury and the military command were to be considered separate. Maximilian could only lead the whole of the troops when he had to appear in the Rhenish district. On 31 May, the Oberland both groups were established and bound themselves to render mutual help for six years.

After the death of Matthias, Holy Roman Emperor and king of Bohemia, the kingdom deprived his successor, Ferdinand II in 1618 of the Bohemian crown, and elected Frederick V, Elector Palatine as King, on August 26 and 27, 1619. After the election as Emperor, Ferdinand conferred with the spiritual electors at Frankfurt, asking for the support of the League.

Now the formation of a confederate army began. With 7,000 men, Bavaria supplied the largest contribution to the army, whose strength was fixed at Würzburg in December 1619, as 21,000 infantry and 4000 cavalry. Commander in chief was Johann Tserclaes, Count of Tilly, a descendant of a Catholic Brabantine family.

Facing the superiority of the League army of 30,000 men confronting the Protestant Union's army of 10,000, on July 3, 1620, the Union agreed to cease all hostilities between both parties during the war in Austria and Bohemia.

The League in War

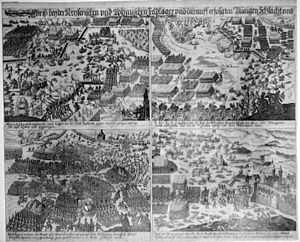

Without the risk of an attack the League could use all its military forces to support the emperor. The same month, the army was relocated to Upper Austria. Tilly won the Battle of White Mountain north of Prague on November 8, 1620, in which half of the enemy forces were killed or captured, losing only 700 men. The Emperor regained control over Bohemia and the first stage of the League's activity during the Thirty Years' War ended.

After the end of the Bohemian War, the League's army fought in central Germany, but was defeated at the Battle of Mingolsheim on April 27, 1622, after which they joined with the Spanish to fight and win the Battle of Wimpfen against the Margrave of Baden-Durlach on May 6. Following these victories, the army captured the city of Heidelberg, the capital of the leader of the Protestant Union, following an eleven-week siege on September 19. The Protestant prince Christian, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg, raised another army, but was defeated at the Battle of Stadtlohn where 13,000 out of his army of 15,000 were lost. This victory virtually ended all Protestant resistance in Germany. This caused Denmark's king Christian IV to enter the Thirty Years' War in 1625 to protect Protestantism and also in a bid to make himself the primary leader of Northern Europe.

The league's army fought and defeated the Danish on August 26–27, 1626 at the Battle of Lutter, destroying more than half the fleeing Danish army.

Because this and other victories by Wallenstein, Denmark was forced to sue for peace at the Treaty of Lübeck. Now, the Catholic League hit its peak. Almost the whole German territories were under their control. The danger of imperial hegemony, resulting from this success, made the Swedish King Gustavus Adolphus become involved in the conflict in 1630.

While Gustavus Adolphus landed his army in Pomerania and tried to make alliances with the leaders of Northern Germany, the League's army laid siege to the city of Magdeburg for two months from March 20, 1631, as the city had promised to support Sweden. On May 20, 40,000 successfully attacked Magdeburg. A massacre of the populace ensued in which 25,000 of the 30,000 inhabitants of the city perished while fires destroyed much of the city.

It is not clear whether the commander in chief of the League's forces, Count Tilly ordered the massacre. Magdeburg was a strategically vital city in the Elbe River region and was needed as a resupply center for the looming fight against the Swedes. Therefore, it would have been logical behavior, not to destroy, but to occupy the town with troops of the League.

In 1630, Ferdinand II dismissed his Generalissimus Wallenstein. Now, the Catholic League was in control of all the Catholic armed forces.

The end of the Catholic League

At the First Battle of Breitenfeld, the Catholic League led by General Tilly was defeated by the Swedish forces. A year later (1632), they met again in the Battle of Rain, and this time General Tilly was killed. The upper hand had now switched from the league to the union, led by Sweden, who were able to attack and capture or destroy the territories of the Catholic League. Even Munich, the capital of Bavaria, was conquered. Thereafter, the German Catholic League did not play a major role in later events.

The Peace of Prague of 30 May 1635, was a treaty between the Holy Roman Emperor, Ferdinand II, and most of the Protestant states of the Empire. It effectively ended the civil war aspect of the Thirty Years' War. The Edict of Restitution of 1629 was effectively revoked, with the terms of the Peace of Augsburg of 1555 being reestablished as at November 12, 1627.

One of the most important regulations was that formal alliances between states of the Empire were prohibited. The armies of the various states were to be unified with those of the Emperor as an army for the Empire as a whole. The result of this clause was the end of the Catholic League, a now prohibited alliance between states of the Empire.

As well as ending the fighting between the various states, the treaty also ended religion as a source of national conflict; the principle of cuius regio, eius religio was established for good within the Empire.

References

- ↑

"German (Catholic) League". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913.

"German (Catholic) League". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913.

| ||||||||