Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament (Sacramento, California)

| Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament | |

|---|---|

|

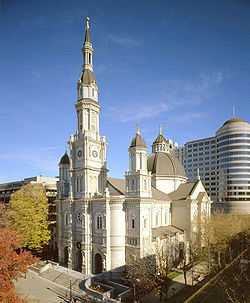

The Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament from the intersection of K and 11th Streets in Downtown Sacramento | |

| |

| 38°34′44.4″N 121°29′31.52″W / 38.579000°N 121.4920889°W | |

| Location |

1017 11th St. Sacramento, California |

| Country | United States |

| Denomination | Roman Catholic Church |

| Website |

www |

| History | |

| Founded | 1886 |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | Bryan J. Klinch[1] |

| Style | Italian Renaissance[2] |

| Completed | June 12, 1889[3] |

| Construction cost | $250,000 (1889 estimate)[4] |

| Specifications | |

| Capacity | 1,400 seats |

| Length | 200 feet (61 m) |

| Width | 100 feet (30 m) |

| Number of domes | One |

| Dome height (outer) | 175 feet (53 m) |

| Number of spires | Three |

| Spire height | Tallest: 215 feet (66 m)[5] |

| Materials | brick, mortar, wood, reinforced concrete, steel frame[6] |

| Administration | |

| Diocese | Diocese of Sacramento |

| Clergy | |

| Bishop(s) | Most Rev. Jaime Soto |

| Rector | Rev. Michael O'Reilly |

Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament in Sacramento is a cathedral of the Roman Catholic Church in the United States. It is the mother church and seat of Jaime Soto, the ordinary bishop of the Diocese of Sacramento. The Cathedral is located downtown at the intersection of 11th and K Streets.

Currently, the cathedral is considered both a religious and civic landmark. It is the mother church of the diocese, which stretches from the southern edge of Sacramento County north to the Oregon border and serves approximately 975,000 Catholics. The diocese encompasses 99 churches in a 42,000 square mile region.[7] The Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament is one of the largest cathedrals west of the Mississippi River.[3] Because of its size, it has sometimes been used as the site of final funeral masses for former Governors of California, most recently that of Pat Brown in 1996.

History

With construction beginning in 1887, Sacramento’s Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament is an example of the strength and history in Sacramento’s architecture. Since many of the buildings date back to the mid-19th century, Sacramento is home to the largest concentration of buildings dating back to the California Gold Rush era in the United States.[8] With a recent restoration project that loops together the Catholic culture, the legacy of gold miners, visions of a vibrant downtown and the sentiments of Sacramentans who spent some of life’s most memorable moments within the church’s walls. The Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament combines Sacramento’s history with its modern day life.

Among the first of thousands to seek his fortune in the Sacramento region during the California Gold Rush, Patrick Manogue had aspirations that differed from many of his fellow fortune seekers. His goal was to earn enough money to finance a trip to Paris, where he planned to enroll in seminary college and become a Roman Catholic priest.

While studying in Paris in 1860, Manogue became enchanted by the cathedrals and their role in a city’s community life. In 1886, Manogue was appointed as Sacramento’s first bishop. Inspired by churches he’d seen in European plazas, Manogue worked to secure property just one block away from the capitol building, with a dream of building a cathedral in Sacramento. Manogue modeled the cathedral after L'Eglise de la Sainte-Trinite (The Church of the Holy Trinity) in Paris. Once completed, there was no cathedral equal in size west of the Mississippi River. The building is a modified basilica form approximately 200 feet (61 m) long and 100 feet (30 m) wide, and it seats 1400 people. The central bell tower rises 215 feet (66 m).[5]

Recent renovation

The architectural style of the church is Italian Renaissance on the exterior and Victorian on the interior.[2] The church has been updated for modern use, but designers tried to keep the church in the original style. Over the years, with repairs, changes in color schemes and changes to the liturgy, the Church lost its stylistic unity.

From August 2003 until November 2005, the Cathedral closed for extensive remodeling to unify the church’s décor from the numerous renovations throughout the years. In this renovation were significant additions, including a Eucharistic chapel, two side chapels, and a large crucifix below the domed crossing. But the largest change was the re-opening of the dome, which was closed in the 1930s for acoustic reasons.[9] The Eucharistic chapel (or Blessed Sacrament Chapel) pays an architectural homage to the chancel screens of medieval churches. It allows for the tabernacle to remain in plain view of the congregation and be in line with the High Altar while also allowing for a private devotional space outside of the celebration of the Mass. The words of the Eucharistic hymn Pange Lingua Gloriosi are inscribed in gold lettering on the screen.

Every part of the cathedral was updated in the restoration ranging from expanded pews to better lighting with decorative painting on the interior walls and ceiling. The massive stained glass windows in the building were cleaned and releaded. The church includes a new bishop’s cathedra (episcopal chair) and ambo of mahogany.

Above the altar hangs a 13-foot (4.0 m) crucifix with a crown overhead that is 14 feet (4.3 m) in diameter. Combined they weigh almost 2,000 lb (910 kg) and are held in place with aircraft cables.

The interior dome of the cathedral, which stands 110 feet (34 m) high, was rebuilt, some 70 years after the original one was blocked from view. The dove in the oculus, with a wingspan of 7 ft (2.1 m), is “a dramatic reminder of the Holy Spirit’s presence in the life of the church, especially in the celebration of the Eucharist,” according to Father James Murphy who was the Rector of the cathedral during its renovation.[5] Sixteen large rondels, each 5 ft (1.5 m) in diameter, decorate the new dome, portraying Eucharistic scenes from Scripture.

An octagonal marble baptismal font with a decorative mosaic is at the entrance to the cathedral. Two side chapels — the Martyrs Chapel and the Chapel of Our Lady and Saints of the Americas — provide a space for private devotion to the saints. Two 20-foot (6.1 m) high murals, painted by artists from EverGreene Painting Studios in New York, adorn the chapels.

The large, weight-bearing columns of the cathedral were hollowed and workers installed 320 LT (330,000 kg) of steel to reinforce the masonry of the cathedral walls. Workers used a powerful epoxy with the steel to bond components to the structure and enable the building to withstand an earthquake measuring 8.0 on the Richter scale.[6]

The cathedral's original organ was removed in 1970 and in 1977 it was replaced with a small nine-rank instrument that was inadequate to serve the cathedral's needs. The Reuter Organ Company constructed and installed a new organ with 15-ranks that incorporates the pipes from the earlier instrument.

The restoration is the largest financial project the diocese has ever undertaken, with the $34 million cost coming from various sources. The diocese’s 2002 capital campaign provided $10 million and another $10 came from diocesan investments. An additional $2 million was raised by cathedral parishioners. Diocesan officials are now conducting a campaign for the remaining $12 million (January 2005 estimate).[2]

Gallery

-

Interior

-

Interior view from the altar

-

The new crucifix after the cathedral's 2004-2005 renovation

-

The cathedral facade from street level.

External links

- A pictoral tour of the recent renovation. The pictoral tour is narrated by Rev. James Murphy, Rector of the Cathedral.

- Inside the Cathedral Renovations (282k PDF)

- The Cathedral Website

Coordinates: 38°34′44″N 121°29′32″W / 38.5790°N 121.49209°W

Notes

- ↑ Diocese of Sacramento: The Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament, page 8. Editions Du Signe, 2005.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Jennifer Garza (17 November 2005). "Cathedral to unveil shiny new face". Sacramento Bee (CSUS.edu). Retrieved 2011-12-29.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "The Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament". Diocese of Sacramento. Retrieved 2011-12-29.

- ↑ Diocese of Sacramento: The Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament, page 28. Editions Du Signe, 2005.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 "Restoration of the Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament Tour Notecards" (PDF). CathedralSacramento.org. Retrieved 2011-12-29.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Sacbee.com

- ↑ "Diocesan Statistics and Counties Map". Diocese of Sacramento. 2009. Retrieved 2011-12-29.

- ↑ "The History of Old Sacramento". Old Sacramento Business Association. Retrieved 2011-12-29.

- ↑ Brian Libby (29 March 2006). "Sacramental Restoration". Architecture Week. Architectureweek.com. Retrieved 2011-12-29.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||