Categorification

In mathematics, categorification is the process of replacing set-theoretic theorems by category-theoretic analogues. Categorification, when done successfully, replaces sets by categories, functions with functors, and equations by natural isomorphisms of functors satisfying additional properties. The term was coined by Louis Crane.

Categorification is the reverse process of decategorification. Decategorification is a systematic process by which isomorphic objects in a category are identified as equal. Whereas decategorification is a straightforward process, categorification is usually much less straightforward, and requires insight into individual situations.

Examples of categorification

One form of categorification takes a structure described in terms of sets, and interprets the sets as isomorphism classes of objects in a category. For example, the set of natural numbers can be seen as the set of cardinalities of finite sets (and any two sets with the same cardinality are isomorphic). In this case, operations on the set of natural numbers, such as addition and multiplication, can be seen as carrying information about products and coproducts of the category of finite sets. Less abstractly, the idea here is that manipulating sets of actual objects, and taking coproducts (combining two sets in a union) or products (building arrays of things to keep track of large numbers of them) came first. Later, the concrete structure of sets was abstracted away – taken "only up to isomorphism", to produce the abstract theory of arithmetic. This is a "decategorification" – categorification reverses this step.

Other examples include homology theories in topology. See also Khovanov homology as a knot invariant in knot theory.

An example in finite group theory is that the ring of symmetric functions is categorified by the category of representations of the symmetric group. The decategorification map sends the Specht module indexed by partition  to the schur function indexed by the same partition:

to the schur function indexed by the same partition:

(essentially following the character map from a favorite basis of the associated Grothendieck group to a representation-theoretic favorite basis of the ring of symmetric functions). This map reflects much of the parallels in structure; for example

![[\mathrm{Ind}_{S_m \otimes S_n}^{S_{n+m}}(S^{\mu} \otimes S^{\nu})] \qquad \text{ and } \qquad s_\mu s_\nu](../I/m/42de676b6612ae7133477baf367da810.png)

have the same decomposition numbers over their respective bases, both given by Littlewood-Richardson coefficients.

Abelian categorifications

For a category  , let

, let  be the Grothendieck group of

be the Grothendieck group of  .

.

Let  be a ring which is free as an abelian group, and let

be a ring which is free as an abelian group, and let  be a basis of

be a basis of  such that the multiplication is positive in

such that the multiplication is positive in  , i.e.

, i.e.

with

Let  be an

be an  -module. Then a (weak) abelian categorification of

-module. Then a (weak) abelian categorification of  consists of an abelian category

consists of an abelian category  , an isomorphism

, an isomorphism  , and exact endofunctors

, and exact endofunctors  such that

such that

- the functor

lifts the action of

lifts the action of  on the module

on the module  , i.e.

, i.e. ![\varphi [F_i] = a_i \varphi](../I/m/1ffda6c5d29f9fe5c885d90b8140ff85.png) , and

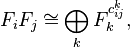

, and - there are isomorphisms

, i.e. the composition

, i.e. the composition  decomposes as the direct sum of functors

decomposes as the direct sum of functors  in the same way that the product

in the same way that the product  decomposes as the linear combination of basis elements

decomposes as the linear combination of basis elements  .

.

See also

- Combinatorial proof, the process of replacing number theoretic theorems by set-theoretic analogues.

- Categorical ring

Further reading

- Baez, John; Dolan, James (1998), "Categorification", in Getzler, Ezra; Kapranov, Mikhail, Higher Category Theory, Contemp. Math. 230, Providence, Rhode Island: American Mathematical Society, pp. 1–36, arXiv:math.QA/9802029.

- Crane, Louis; Yetter, David N. (1998), "Examples of categorification", Cahiers de Topologie et Géométrie Différentielle Catégoriques 39 (1): 3–25.

- Mazorchuk, Volodymyr, Lectures on Algebraic Categorification, QGM Master Class Series, European Mathematical Society.

- Savage, Alistair, Introduction to Categorification.

- Khovanov, Mikhail; Mazorchuk, Volodymyr; Stroppel, Catharina (2009), "A brief review of abelian categorifications", Theory Appl. Categ. 22 (19): 479–508, arXiv:math.RT/0702746.