Catacombs of Paris

| Catacombes de Paris | |

|---|---|

|

Entrance to the Catacombs | |

| Established | 1810 |

| Location | Place Denfert-Rochereau, 75014 Paris |

| Collections | Underground quarries of Paris in the late 18th century |

| Website | Les Catacombes de Paris |

The Catacombs of Paris or Catacombes de Paris are underground ossuaries in Paris, France. Located south of the former city gate (the "Barrière d’Enfer" at today's Place Denfert-Rochereau), the ossuaries hold the remains of about six million people[1] and fill a renovated section of caverns and tunnels that are the remains of historical stone mines, giving it its reputation as "The World's Largest Grave". Opened in the late 18th century, the underground cemetery became a tourist attraction on a small scale from the early 19th century, and has been open to the public on a regular basis from 1874. Following an incident of vandalism, it was closed to the public in September 2009 and reopened on 19 December of the same year.[2]

The Catacombs are one of the 14 City of Paris Museums that have been incorporated since January 1, 2013, in the public institution Paris Musées. The official name for the catacombs is l'Ossuaire Municipal. Although this cemetery covers only a small section of underground tunnels comprising "les carrières de Paris" ("the quarries of Paris"), Parisians today often refer to the entire tunnel network as "the catacombs".

History

Background

Cemeteries in Paris

Paris' earliest burial grounds were to the southern outskirts of the Roman-era Left Bank city. In ruins after the Roman empire's 5th-century fall and the ensuing Frankish invasions, Parisians eventually abandoned this settlement for the marshy Right Bank: from the 4th century, the first known settlement there was on higher ground around a Saint-Etienne church and burial ground (behind today's Hôtel de Ville), and Right Bank urban expansion began in earnest after other ecclesiastical landowners filled in the marshlands from the late 10th century. Thus, instead of burying its dead away from inhabited areas as per usual human customs, the Paris Right Bank settlement began its life with cemeteries at its very centre.

The most central of these cemeteries, a burial ground around the 5th-century Notre-Dame-des-Bois church, became the property of the Saint-Opportune parish after the original church was destroyed by the 9th-century Norman invasions. When it became its own parish under the 'Saints Innocents' church from 1130, this burial ground, filling the land between today's rue Saint-Denis, rue de la Ferronnerie, rue de la Lingerie and the rue Berger, had become the City's principal cemetery.

By the end of the same century 'Saints Innocents' was neighbour to the principal Parisan Les Halles marketplace, and already filled to overflowing. To make room for more burials, the long-dead were exhumed and their bones packed into the roofs and walls of 'charnier' galleries built to the inside of the cemetery walls. By the end of the 19th century, the central burial ground was a two metre high mound of earth filled with centuries of Parisian dead, disease, famine, wars, plus the remains from the Hôtel-Dieu hospital and the Morgue; other Parisian parishes had their own burial grounds, but the conditions in Les Innocents cemetery were by far the worst.

A series of ineffective decrees limiting the use of the cemetery did little to remedy the situation, and it wasn't until the late 18th century that it was decided to create three new large-scale suburban burial grounds on the outskirts of the city, and to condemn all existing parish cemeteries within city limits.

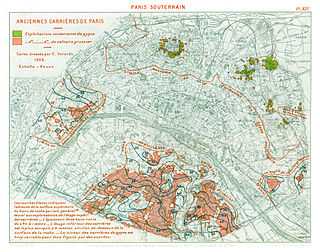

Former mines in Paris

The Left Bank is centered on rich limestone deposits. This stone built much of the city, but it was extracted in suburban locations away from any habitation. Because of the post 12th-century haphazard mining technique of digging wells down to the deposit and extracting it horizontally along the vein until depletion, many of these (often illicit) mines were uncharted, and when depleted, often abandoned and forgotten. Paris had annexed its suburbs many times over the centuries, and by the 18th century many of its arrondissements (administrative districts) were or included previously mined territories.

The undermined state of the Left Bank was known to architects as early as the early 17th-century construction of the Val-de-Grâce hospital (most of its building expenses were sunk into its foundations), but a series of mine cave-ins beginning in 1774 with the collapse of a house along the 'rue d'Enfer' (near today's crossing of the Avenue Denfert-Rochereau and the boulevard Saint-Michel) led King Louis XVI to name a commission to investigate the state of the Parisian underground. This led to the creation of the inspection Générale des Carrières (Inspection of Mines) service.

Creation, renovation

The need to eliminate Les Innocents gained urgency from the 30th of May 1780, when a basement wall in a property adjoining the cemetery gave way under the weight of the mass grave behind it. The cemetery was closed to the public and all intra muros (Latin for "within the walls", as of a city[3]) burials were definitely forbidden by the end of the same year, but the problem of what to do with the contents of intra muros cemeteries remained.

Mine consolidations were still under way that year, and the underground around the site of the 1777 collapse that had begun the project had already become a series of stone and masonry inspection passageways that ensured the solidity of the ground under the streets running above them. The mine renovation and cemetery closures were both questions within the jurisdiction of the Police Prefect of the time, Police Lieutenant-General Alexandre Lenoir, and since the Prefect had been directly involved in the creation of a mine inspection service, he was firmly behind an idea of moving Parisian dead to the newly renovated subterranean passageways that had been circulating since 1782. After deciding to further renovate the 'Tombe-Issoire' passageways for their future role as an underground sepulchre, the idea became law in late 1785.

A well within a walled property above one of the principal subterranean passageways was dug to receive Les Innocents' unearthed remains, and the property itself was transformed into a sort of museum for all the headstones, sculptures and other artifacts recuperated from the former cemetery. Beginning from an opening ceremony on the 7th of April the same year, the route between Les Innocents and the 'clos de la Tombe-Issoire' became a nightly procession of black cloth-covered wagons carrying the millions of Parisian dead. It would take two years to empty the majority of Paris cemeteries.[4]

The catacombs in their first years were a pell-mell bone repository, but Louis-Étienne Héricart de Thury, head of the Paris mine inspection service from 1810, undertook renovations that would transform the underground caverns into a visitable mausoleum. In addition to directing the stacking of skulls and femurs into the patterns seen in the catacombs today, he used the cemetery decorations he could find (formerly stored on the Tombe-Issoire property, many had disappeared following the 1789 Revolution) to complement the walls of bones. Also created were a room dedicated to the display of the various minerals found under Paris, and another showing various skeletal deformities found during the catacombs' creation and renovation. He also added monumental tablets and archways bearing inscriptions (that some found of questionable taste) that were warnings, descriptions or 'poetic light' about the nature of the ossuary, and, for the safety of eventual visitors, it was walled from the rest of the Paris Left Bank already-extensive underground tunnel network.

Visiting

The Catacombs of Paris became a 'curiosity' for more privileged Parisians from their creation, the first known visitor of note being the Count of Artois (later France's King Charles X) in 1787, but the first known public visits only began after its renovation into a proper ossuary and the 1814-1815 war. First allowed only a few times a year with the permission of an authorised Mines inspector, then frequently in visits led by any mine overseer, a flow of often unscrupulous visitors degraded the ossuary to a point where the permission-only rule was restored from 1830, and the catacombs were closed completely from 1833 because of church opposition to exposing 'sacred' human bones to public display. Open again for four visits a year from 1850, public demand moved the government to allow monthly visits from 1867, bi-weekly visits on the first and third Saturday of each month from 1874 (with an extra opening for the November 1 toussaint holiday), and weekly visits during the 1878, 1889 (the most visitors yet that year) and 1900 World's Fair Expositions.

The entry to the catacombs is in the western pavilion of the former Barrière d'Enfer city gate. After descending a narrow spiral stone stairwell of 19 meters to the darkness and silence broken only by the gurgling of a hidden aqueduct channeling local springs away from the area, and after passing through a long (about 1.5 km) and twisting hallway of mortared stone, visitors find themselves before a sculpture that existed from a time before this part of the mines became an ossuary, a model of France's Port-Mahon fortress created by a former Quarry Inspector. Soon after, they find themselves before a stone portal, the ossuary entry, with the inscription Arrête! C'est ici l'empire de la Mort ('Stop! This is the Empire of the Dead").

Beyond begin the halls and caverns of walls of carefully arranged bones. Some of the arrangements are almost artistic in nature, such as a heart-shaped outline in one wall formed with skulls embedded in surrounding tibias; another is a round room whose central pillar is also a carefully created 'keg' bone arrangement. Along the way one would find other 'monuments' created in the years before catacomb renovations, such as a source-gathering fountain baptised "La Samaritaine" because of later-added engravings. There are also rusty gates blocking passages leading to other 'unvisitable' parts of the catacombs – many of these are either un-renovated or were too un-navigable for regular tours.

Other events in the catacombs

- Bodies of the dead from the riots in the Place de Grève, the Hôtel de Brienne, and Rue Meslée were put in the catacombs on 28 and 29 August 1788.

- The tomb of the Val-de-Grâce hospital doorkeeper, Philibert Aspairt, lost in the catacombs in 1793 and found 11 years later, is located in the catacombs on the spot where his body was found.

- In 1871, communards killed a group of monarchists there.

- During World War II, Parisian members of the French Resistance used the tunnel system.

- The Nazis established an underground bunker below Lycée Montaigne, a high school in the 6th arrondissement.

- In 2004, police discovered a fully equipped movie theater in one of the caverns. It was equipped with a giant cinema screen, seats for the audience, projection equipment, film reels of recent thrillers and film noir classics, a fully stocked bar, and a complete restaurant with tables and chairs. The source of its electrical power and the identity of those responsible remain unknown.[5]

Disruption of surface structures

Although the catacombs offered space to bury the dead, they presented disadvantages to building structures; because the catacombs are directly under the Paris streets, large foundations cannot be built and cave-ins have destroyed buildings. For this reason, there are few tall buildings in this area.[6]

References

- ↑ "Catacombs A Timeless Journey". Les Catacombes de Paris [Catacombs of Paris]. Retrieved 2015-01-05.

- ↑ "Paris catacombs Vandalized, closed for repair". www.gadling.com. 2009-09-22. Retrieved 2011-02-09.

- ↑ "intra muros". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 2015-01-06.

- ↑ "Paris Catacombs Visitor Information". Retrieved 2011-02-25.

- ↑ "La Mexicaine De Perforation". Urban-Resources. 2004. Retrieved August 23, 2004.

- ↑ "Inside France's Empire of the Dead...". Daily Mail. 6 August 2012.

Further reading

- Quigley, Christine (2001) Skulls and skeletons: human bone collections and accumulations. McFarland, Jefferson, NC, USA. pp. 22–29

- Riordan, Rick (2008) The 39 Clues Book 1: The Maze of Bones. Scholastic Inc. pp. 169–176

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Catacombs of Paris. |

Coordinates: 48°50′02.43″N 2°19′56.36″E / 48.8340083°N 2.3323222°E