Casus irreducibilis

In algebra, casus irreducibilis (Latin for "the irreducible case") is one of the cases that may arise in attempting to solve a cubic equation with integer coefficients with roots that are expressed with radicals. Specifically, if a cubic polynomial is irreducible over the rational numbers and has three real roots, then in order to express the roots with radicals, one must introduce complex-valued expressions, even though the resulting expressions are ultimately real-valued.

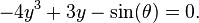

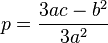

One can decide whether a given irreducible cubic polynomial is in casus irreducibilis using the discriminant D, via Cardano's formula.[1] Let the cubic equation be given by

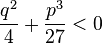

Then the discriminant D appearing in the algebraic solution is given by

- If D < 0, then the polynomial has two complex roots, so casus irreducibilis does not apply.

- If D = 0, then there are three real roots, and two of them are equal and can be found by the Euclidean algorithm and the quadratic formula. All roots are real and expressible by real radicals. The polynomial is not irreducible.

- If D > 0, then there are three distinct real roots. Either a rational root exists and can be found using the rational root test, in which case the cubic polynomial can be factored into the product of a linear polynomial and a quadratic polynomial, the latter of which can be solved via the quadratic formula; or no such factorization can occur, so the polynomial is casus irreducibilis: all roots are real, but require complex numbers to express them in radicals.

Formal statement and proof

More generally, suppose that F is a formally real field, and that p(x) ∈ F[x] is a cubic polynomial, irreducible over F, but having three real roots (roots in the real closure of F). Then casus irreducibilis states that it is impossible to find any solution of p(x) = 0 by real radicals.

To prove this, note that the discriminant D is positive. Form the field extension F(√D). Since this is F or a quadratic extension of F (depending in whether or not D is a square in F), p(x) remains irreducible in it. Consequently, the Galois group of p(x) over F(√D) is the cyclic group C3. Suppose that p(x) = 0 can be solved by real radicals. Then p(x) can be split by a tower of cyclic extensions

At the final step of the tower, p(x) is irreducible in the penultimate field K, but splits in K(∛α) for some α. But this is a cyclic field extension, and so must contain a primitive root of unity.

However, there are no primitive 3rd roots of unity in a real closed field. Indeed, suppose that ω is a primitive 3rd root of unity. Then, by the axioms defining an ordered field, ω, ω2, and 1 are all positive. But if ω2>ω, then cubing both sides gives 1>1, a contradiction; similarly if ω>ω2.

Solution in non-real radicals

The equation  can be depressed to a monic trinomial by dividing by

can be depressed to a monic trinomial by dividing by  and substituting

and substituting  (the Tschirnhaus transformation), giving the equation

(the Tschirnhaus transformation), giving the equation

where

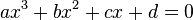

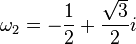

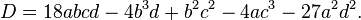

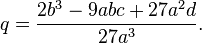

Then regardless of the number of real roots, by Cardano's solution the three roots are given by

where  (k=1, 2, 3) is a cube root of 1:

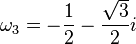

(k=1, 2, 3) is a cube root of 1:  ,

,  , and

, and  , where i is the imaginary unit.

, where i is the imaginary unit.

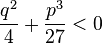

Casus irreducibilis occurs when none of the roots is rational and when all three roots are distinct and real; the case of three distinct real roots occurs if and only if  , in which case Cardano's formula involves first taking the square root of a negative number, which is imaginary, and then taking the cube root of a complex number (which cannot itself be placed in the form

, in which case Cardano's formula involves first taking the square root of a negative number, which is imaginary, and then taking the cube root of a complex number (which cannot itself be placed in the form  with specifically given expressions in real radicals for

with specifically given expressions in real radicals for  and

and  , since doing so would require independently solving the original cubic). Note that even in the reducible case in which one of three real roots is rational and hence can be factored out by polynomial long division, Cardano's formula (unnecessarily in this case) expresses that root (and the others) in terms of non-real radicals.

, since doing so would require independently solving the original cubic). Note that even in the reducible case in which one of three real roots is rational and hence can be factored out by polynomial long division, Cardano's formula (unnecessarily in this case) expresses that root (and the others) in terms of non-real radicals.

Non-algebraic solution in terms of real quantities

While casus irreducibilis cannot be solved in radicals in terms of real quantities, it can be solved trigonometrically in terms of real quantities.[2] Specifically, the depressed monic cubic equation  is solved by

is solved by

These solutions are in terms of real quantities if and only if  — i.e., if and only if there are three real roots.

— i.e., if and only if there are three real roots.

Relation to angle trisection

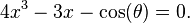

The distinction between the reducible and irreducible cubic cases with three real roots is related to the issue of whether or not an angle with rational cosine or rational sine is trisectible by the classical means of compass and unmarked straightedge. If the cosine of an angle  is known to have a particular rational value, then one third of this angle has a cosine that is one of the three real roots of the equation

is known to have a particular rational value, then one third of this angle has a cosine that is one of the three real roots of the equation

Likewise, if the sine of  is known to have a particular rational value, then one third of this angle has a sine that is one of the three real roots of the equation

is known to have a particular rational value, then one third of this angle has a sine that is one of the three real roots of the equation

In either case, if the rational root test reveals a real root of the equation, x or y minus that root can be factored out of the polynomial on the left side, leaving a quadratic that can be solved for the remaining two roots in terms of a square root; then all of these roots are classically constructible since they are expressible in no higher than square roots, so in particular  or

or  is constructible and so is the associated angle

is constructible and so is the associated angle  . On the other hand, if the rational root test shows that there is no real root, then casus irreducibilis applies,

. On the other hand, if the rational root test shows that there is no real root, then casus irreducibilis applies,  or

or  is not constructible, the angle

is not constructible, the angle  is not constructible, and the angle

is not constructible, and the angle  is not classically trisectible.

is not classically trisectible.

Generalization

Casus irreducibilis can be generalized to higher degree polynomials as follows. Let p ∈ F[x] be an irreducible polynomial which splits in a formally real extension R of F (i.e., p has only real roots). Assume that p has a root in  which is an extension of F by radicals. Then the degree of p is a power of 2, and its splitting field is an iterated quadratic extension of F.[3]

which is an extension of F by radicals. Then the degree of p is a power of 2, and its splitting field is an iterated quadratic extension of F.[3]

Casus irreducibilis for quintic polynomials is discussed by Dummit.[4]:p.17

Notes

References

- Cox, David A. (2012), Galois Theory, Pure and Applied Mathematics (2nd ed.), John Wiley & Sons, doi:10.1002/9781118218457, ISBN 978-1-118-07205-9. See in particular Section 1.3 Cubic Equations over the Real Numbers (pp. 15–22) and Section 8.6 The Casus Irreducibilis (pp. 220–227).

- van der Waerden, Bartel Leendert (2003), Modern Algebra I, F. Blum, J.R. Schulenberg, Springer, ISBN 978-0-387-40624-4

![F\sub F(\sqrt{\Delta})\sub F(\sqrt{\Delta}, \sqrt[p_1]{\alpha_1}) \sub\cdots \sub K\sub K(\sqrt[3]{\alpha})](../I/m/452c86bdcc253a4fda23893449131056.png)

![t_k = \omega_k \sqrt[3]{-{q\over 2}+ \sqrt{{q^{2}\over 4}+{p^{3}\over 27}}} + \omega_k^2 \sqrt[3]{-{q\over 2}- \sqrt{{q^{2}\over 4}+{p^{3}\over 27}}}](../I/m/6e8b6d327924f18c60b9dd64a7a3ac50.png)