Castropignano

| Castropignano | ||

|---|---|---|

| Comune | ||

| Comune di Castropignano | ||

|

Castello d'Evoli by night | ||

| ||

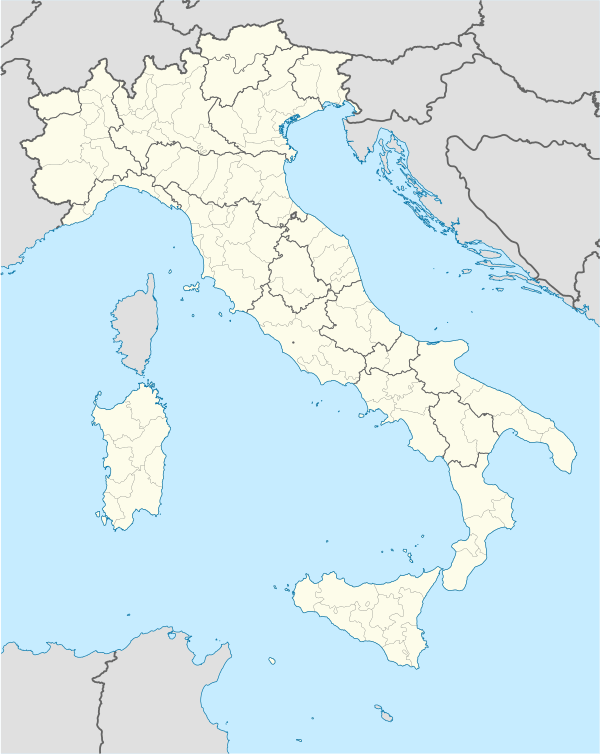

Castropignano Location of Castropignano in Italy | ||

| Coordinates: 41°37′N 14°34′E / 41.617°N 14.567°ECoordinates: 41°37′N 14°34′E / 41.617°N 14.567°E | ||

| Country | Italy | |

| Region | Molise | |

| Province | Campobasso (CB) | |

| Frazioni | Roccaspromonte | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor | Carmine Brunetti | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 27.0 km2 (10.4 sq mi) | |

| Elevation | 590 m (1,940 ft) | |

| Population (2007)[1] | ||

| • Total | 1,079 | |

| • Density | 40/km2 (100/sq mi) | |

| Demonym | Castropignanesi | |

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | |

| • Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | |

| Postal code | 86010 | |

| Dialing code | 0874 | |

| Website | www.castropignano.com | |

Castropignano is a comune (municipality) in the Province of Campobasso in the Italian region Molise, located about 10 kilometres (6 mi) northwest of Campobasso.

It is home to a medieval castle, the Castello d'Evoli, built in the mid-14th century, perhaps over the remains of a Samnite fortress.

Castropignano is a small town situated at an elevation of 620 metres (2,030 ft) above sea level in the Molise region in the Province of Campobasso. Because of its elevation it is often referred to as the "Balcony Over The Biferno River Valley". From the town one could see a picturesque panoramic view of the surrounding towns and hillsides. For comparison purposes, the Niagara Region is at an approximate elevation of 180 metres (600 ft) above sea level and thousands of miles from the sea, while Castropignano at an elevation of 620 metres (2,034 ft) is less than 32 kilometres (20 mi) from the sea.

The history book written by Raffaele Sardella states that the beginning of Castropignano occurred during the Iron Age (1000 BC) when two tribes occupied two hills because it provided better defense and security. The two initial tribes occupied the hills that are now called "Colle" and "Trivecchia". At the place of the castle was a fortress where the population would gather during perilous times or times when the defence requirements reached to an extreme level. It was quite common for the Italic peoples of this age to live in open villages, to which a fortress (usually a hill-top with a rough fence of pointed stakes) might be attached as a place of refuge. Two main branches of dialects developed, the "Umbrian" of the north and the "Oscan" of the southern Apennine districts.

During the time of the Roman Republic and the Samnites, Castropignano was surrounded by a wall with a primary and a secondary entrance. The Samnites were people of central southern Italy, a hardy race of shepherds and farmers with no marked differences in wealth and consequently without a distinct governing class. The Romans had at least three wars with these people of the mountains and they learned some hard lessons, in fact they had to reform their military methods in order to overtake and claim a victory in the year 290. The first Samnite war (343–341 BC) resulted in Roman control of northern Campania; the second (327–321, 316–304 BC) prevented Samnite control of Apulia, Lucania, and southern Campania; the third (298–290 BC) involved and decided the destiny of all peninsular Italy. The Samnites continued to fight in the Social War and the Civil against Sulla (138–78 BC), a Roman general, provincial governor and consul who was proclaimed dictator and was deposed three years later. He slaughtered all the Samnite he could. He, after having numerous battles observed that the Samnite, almost without exception, remained in one body, and with one sole intention, so that they had even marched upon Rome itself, given them battle under the walls, and as he had issued orders to take no prisoners, many of them were cut to pieces on the field, while the remainder, said to be about three to four thousand men, who threw up their arms, were led off to the Villa Publica in the Campus Martius, and were shut in; three days after soldiers were sent in who massacred the whole; and when Sulla drew up his conscription list, he did not rest satisfied until he had destroyed, or driven from Italy, every one who bore a Samnite name. To those who reproached him for his animosity, he replied that he had learned by experience that not a single Roman could rest in peace so long as any of the Samnites survived.

Written accounts in the history of the area make it clear that during the 80 years of war between the Samnites and the Romans the area around the location of the town was found to be at the centre of destruction and many bloody battles. During the year 294 BC the town had the Roman name, "Palumbinum" ( This reference was found in Book 10, Chapter 45 of the Story of Rome by, Tito Livio After unifying Italy Augustus ( 63 BC – 14 AD), Rome's first emperor divided it into eleven administrative districts. One of the districts [known today as eastern Campania, Molise; Abruzzo ] was inhabited by Samnites, Fretani, Marrucini, Marsi, Pelogni, Aequiculli, Vestini and Sabini. The Castropignano area was occupied by a Roman Consulate called Lucio Spurio Carvillo, whose Latin name was Castrum or Castra Pineani. The Romans brought slavery and taxes. For years after the coming of Jesus Christ, the Romans continued to bring fear to the Samnites and for that reason they frequently kept in hiding. This was powerfully demonstrated on the walls of the Roman Sepino (Atilia di Sepino). Except for the Samnites, no one was capable of an attack on Imperial Rome during the first century AD. A Samnite named Pentri, because of his strength and courage as a gladiator and later because of his military contribution to the extension of the Roman Empire, was made a citizen of Rome.

With all probability, our faith in Christ Jesus came through our ancestors directly from Rome because half of the Samnite and Roman legions had converted to the new religion. The barbaric states of Longobardy, Normans, and Bulgarians had difficulty attracting themselves to any union because of religious differences. Since the year 1000/1200 the Castropignano area was directly connected to the Holy See and as time passed it became a dependent member of the Diocese of Trivento.

After the fall of the Roman Empire (around 476 AD), Castropignano was inhabited by a colony of Bulgarians who were similar in behaviour and conduct to the Slavs and Czechs. During that time a Bulgarian chief priest lived in the town and this influence from outside the town created a new class of people. Whoever entered the town from a neighboring town was welcome and was exempted from punishment for no matter what offense that he had done in the other town. For this reason the Bulgarians dominated Castropignano and at that time people referred to the town as "Castropignano of the Bulgarians who triumph with all the bad habits of hoodlums". The result was that during the eight centuries to the year 1000 two languages were spoken in Castropignano, Italian dialect and Bulgarian.

In the year 1114 a person named Gulielmo became known. His last name was not known because in those days it was customary to drop the family name and then to become known by the place of origin. For example, Leonardo da Vinci meant Leonardo from the town of Vinci. Gulielmo's first male descendant was called "Vito di Castropignano" or Vito of Castropignano. Vito had two daughters. Tomasia was married to Petrillo Minutolo and the second daughter named Claricia was married to Giovanni d'Evoli, baron of Frosolone. An argument developed between Minutolo and d'Evoli. Eventually d'Evoli paid Minutolo off so that he could become the baron of Castropignano. The d'Evoli family had obtained the title of Duke of Castropignano. During the nine centuries of their tenure Castropignano was central to their control and exploitation of the tratturo transhumance passage of herds from Southern lowland winter pastures to upland Apennine pastures further North. Following the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy in 1815, the recognition of the communes established in the preceding Napoleonic period brought the d'Evoli to an end.[2]

Etymology

The name Castropignano appeared for the first time in a thesis written by Michelangelo Ziccardi, a Molisan archeologist. Ziccardi supports the theory that Castropignano as it is known today and the place Palombinum that is mentioned by Tito Livio in the Story of Rome where a war with the Samnites was described are the same place. Ziccardi also concluded in his thesis that Palombinum in the dialect day-to-day language of the Samnites at that time meant "a fortress". The fact that Castropignano was a fortified place is demonstrated by a natural defensive wall that exists with the rock "La Fata". The remains of this rock wall show that during the period of the Samnite wars, the natural position of the town and the North-West position of the castle was perfect for defensive purposes. Tito Livio described the conquest of Palombinum [Year 459 of Rome (294 AD)] with the words, "Carvilio has already occupied Velia (it is questionable whether Velia meant Torella del Sannio, Casalchiprano, or S. Angelo Limosano), Palumbino and Herculaneum (it is questionable whether Herculaneum could be Campobasso or Oratino). Velia was taken in a few days and within the end of this day the wall of Palombinum will be taken".

Tito Livio writes that Palombino (Castropignano) opened the door to the Romans without any resistance. So, Castropignano, even with its surrounding wall and with its natural position, could not fashion any absolute pressure during the one-day siege. It can be argued then, that the inhabitants were stopped without a battle because of the large number of deaths they had suffered in a previous war or because with the fall of Herculaneum and Velia, they felt that they had lost their support so it was futile to offer any resistance.

Other studies into the history have written that Castropignano was actually derived from "Castra Pinaria", others say that it was derived from "Castra Pugnarum". Casa Pinara indicated a fortress or a fortified place for defensive purposes and was governed by a Roman military family called Pinaria. Each of the two words in "Castra Pugnarium" has a special meaning. Castra meant "a fortified place" while Pugnarium meant "an area of bloody confrontations" between the Samnites and the Romans. Early writings of a woman called Carmela Ciamarra describe an early plan of Castropignano presented by a monk from Limosano called Zagomo Iacovone to a Roman consul named "Castrum Pineani".

It can be concluded then that Castropignano was called:

- "Palumbinum" during the time of the Samnite wars

- "Castrum Pineani" during the time occupied by the Romans

- "Castro Pignano" in the medieval time period

Finally, documentation in the parochial archives of Chiesa Madre, the main church of Castropignano, exists a baptismal registration signed by a Carlo Borsella, who was bursar and parish priest of the town "Castri Pineani" in the year 1840. Since the church always operated in the Latin language, all writings were in Latin and so the town was referred to as "Castri Pineani". The final reasoning that explains why Pineani appears in the parochial register is that he was born a Roman consul and it was highly probable that the Romans abolished the Palombinum name and adopted the name Castrum or Castra Pineani which meant the "Fortress of Pineano". Over the years Pineano transformed to Pagnano and finally "Castro Pignano". Members of an immigrant family with the surname "Castelpagnano", now residing in San Jose, California, are descendants of the Roman Consul Pineano.

Crest

The crest contains three towers encircled by a wall with one door. On each side of the fortress is a letter "C" and "P". The letters indicate the name "Castrum Pineani" the Roman Consul stationed in the area at that time.

An older design of the crest can be found in the church of San Salvatore, on the left side when you enter the church. The three towers indicate the three old fortresses that existed in the old days, Trivecchia, Colle, and Castello.

- NOTE: The history book by Raffaele Sardella makes no reference as to the origin and meaning of the crown above the three towers that is now present on the town crest.

References

- ↑ All demographics and other statistics: Italian statistical institute Istat.

- ↑ History of Naples

- The history book written by Raffaele Sardella