Casey at the Bat

"Casey at the Bat: A Ballad of the Republic Sung in the Year 1888" is a baseball poem written in 1888 by Ernest Thayer. First published in The San Francisco Examiner on June 3, 1888, it was later popularized by DeWolf Hopper in many vaudeville performances.[1] It has become one of the best-known poems in American literature. The poem was originally published anonymously (under the pen name "Phin", based on Thayer's college nickname, "Phineas").[2]

Synopsis

A baseball team from the fictional town of Mudville (implied to be the home team) is losing by two runs in their last inning. Both the team and its fans (a crowd of 5,000, according to the poem) believe they can win if Mighty Casey, Mudville's star player, gets up to bat. However, Casey is scheduled to be the fifth batter of the inning, and the first two batters (Cooney and Barrows) fail to get on base. The next two batters (Flynn and Jimmy Blake) are perceived to be weak hitters with little chance of reaching base to allow Casey a chance to bat.

Surprisingly, Flynn hits a single, and Blake follows with a double that allows Flynn to reach third base. Both runners are now in scoring position and Casey represents the potential winning run. Casey is so sure of his abilities that he does not swing at the first two pitches, both called strikes. On the last pitch, the overconfident Casey strikes out swinging, ending the game and sending the crowd home unhappy.

Text

The text is filled with references to baseball as it was in 1888, which in many ways is not far removed from today's version. As a work, the poem encapsulates much of the appeal of baseball, including the involvement of the crowd. It also has a fair amount of baseball jargon that can pose challenges for the uninitiated.

This is the complete poem as it originally appeared in The San Francisco Examiner, with commentary. After publication, various versions with minor changes were produced.

- The outlook wasn't brilliant for the Mudville Nine that day;

- The score stood four to two, with but one inning more to play,

- And then when Cooney died at first, and Barrows did the same,

- A sickly silence fell upon the patrons of the game.

"No one imagines that 'Casey' is great in the sense that the poetry of Shakespeare or Dante is great; a comic ballad obviously must be judged by different standards. One doesn’t criticize a slice of superb apple pie because it fails to taste like crepes suzette. Thayer was only trying to write a comic ballad, with clanking rhymes and a vigorous beat, that could be read quickly, understood at once, and laughed at by any newspaper reader who knew baseball. Somehow, in harmony with the curious laws of humor and popular taste, he managed to produce the nation’s best-known piece of comic verse—a ballad that began a native legend as colorful and permanent as that of Johnny Appleseed or Paul Bunyan."[2]

- A straggling few got up to go in deep despair. The rest

- Clung to that hope which springs eternal in the human breast;

- They thought, if only Casey could get but a whack at that –

- They'd put up even money, now, with Casey at the bat.

- But Flynn preceded Casey, as did also Jimmy Blake,

- And the former was a lulu and the latter was a fake

- So upon that stricken multitude grim melancholy sat,

- For there seemed but little chance of Casey's getting to the bat.

- But Flynn let drive a single, to the wonderment of all,

- And Blake, the much despised, tore the cover off the ball;

- And when the dust had lifted, and the men saw what had occurred,

- There was Jimmy safe at second and Flynn a-hugging third.

- Then from 5,000 throats and more there rose a lusty yell;

- It rumbled through the valley, it rattled in the dell;

- It knocked upon the mountain and recoiled upon the flat,

- For Casey, mighty Casey, was advancing to the bat.

- There was ease in Casey's manner as he stepped into his place;

- There was pride in Casey's bearing and a smile on Casey's face.

- And when, responding to the cheers, he lightly doffed his hat,

- No stranger in the crowd could doubt 'twas Casey at the bat.

- Ten thousand eyes were on him as he rubbed his hands with dirt;

- Five thousand tongues applauded when he wiped them on his shirt.

- Then while the writhing pitcher ground the ball into his hip,

- Defiance gleamed in Casey's eye, a sneer curled Casey's lip.

- And now the leather-covered sphere came hurtling through the air,

- And Casey stood a-watching it in haughty grandeur there.

- Close by the sturdy batsman the ball unheeded sped-

- "That ain't my style," said Casey. "Strike one," the umpire said.

- From the benches, black with people, there went up a muffled roar,

- Like the beating of the storm-waves on a stern and distant shore.

- "Kill him! Kill the umpire!" shouted someone on the stand;

- And it's likely they'd a-killed him had not Casey raised his hand.

- With a smile of Christian charity great Casey's visage shone;

- He stilled the rising tumult; he bade the game go on;

- He signaled to the pitcher, and once more the spheroid flew;

- But Casey still ignored it, and the umpire said, "Strike two."

- "Fraud!" cried the maddened thousands, and echo answered fraud;

- But one scornful look from Casey and the audience was awed.

- They saw his face grow stern and cold, they saw his muscles strain,

- And they knew that Casey wouldn't let that ball go by again.

- The sneer is gone from Casey's lip, his teeth are clenched in hate;

- He pounds with cruel violence his bat upon the plate.

- And now the pitcher holds the ball, and now he lets it go,

- And now the air is shattered by the force of Casey's blow.

- Oh, somewhere in this favored land the sun is shining bright;

- The band is playing somewhere, and somewhere hearts are light,

- And somewhere men are laughing, and somewhere children shout;

- But there is no joy in Mudville — mighty Casey has struck out.

Inspiration

In 1887, National League star Mike "King" Kelly became famous—arguably the first baseball player to become so overnight—when Boston paid Chicago a record $10,000 for him. He had a personality that fans liked to cheer or jeer. He also is associated with "Casey at the Bat," and a once well-known song and expression for avoiding danger, such as being tagged out: "Slide, Kelly, Slide!" In 1927, an MGM silent movie with a baseball theme was called Slide, Kelly, Slide.

As of 1887, Kelly was especially known as the "$10,000 Beauty." In 1881, actress Louise Montague had been so dubbed after winning a $10,000 contest for handsomest woman in the world.[3]

After the 1887 season, Kelly went on a playing tour to San Francisco. Thayer, who would write "Casey" in 1888, covered the San Francisco leg for the San Francisco Examiner. Although Thayer said he literally chose the name "Casey" after a non-player of Irish ancestry he once knew, open to debate is who, if anyone, he modeled Casey's baseball situations after. The best big league candidate is Kelly, the most colorful, top player of the day of Irish ancestry. Thayer, in a letter he wrote in 1905, singles out Kelly as showing "impudence" in claiming to have written the poem. If he still felt offended, Thayer may have steered later comments away from connecting Kelly to it. The author of the 2004 definitive bio of Kelly – which included a close tracking of his vaudeville career—did not find Kelly claiming to have been the author.[4]

Before the playing tour, Kelly's plans to go on it had drawn colorful comment in San Francisco. In August, the San Francisco Call said, "My, what a time the small boy will have following him around the streets, styling their nines the 'Only Kells,' and asking him how he liked [new National Leaguer George Van Haltren, who was living in the offseason in San Francisco]. But it is a great thing to be distinguished, you know.'"[5]

Also, while Kelly was in San Francisco on the tour, the $10,000 check arrived with which Boston had bought him. It will "at once be placed on exhibition in a prominent show window," the San Francisco Chronicle said. "The check bears the names of [Boston club President] A.H. Soden of Boston as payer and [Chicago club President] A.G. Spalding of Chicago as payee."[5]

Plagiarism

A month after the poem was published, it was reprinted as "Kelly at the Bat" in the New York Sporting Times.[6] Aside from leaving off the first five verses, the only changes from the original are substitutions of Kelly for Casey, and Boston for Mudville. Kelly, then of the Boston Beaneaters, was one of baseball's two biggest stars at the time (along with Cap Anson).[4]

In 1897, "Current Literature" noted the two versions and said, "The locality, as originally given, is Mudville, not Boston; the latter was substituted to give the poem local color."[7]

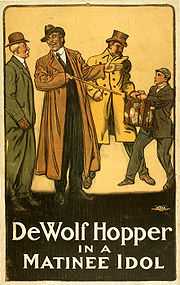

Live performances

DeWolf Hopper gave the poem's first stage recitation on August 14, 1888, at New York's Wallack Theatre as part of the comic opera Prinz Methusalem in the presence of the Chicago and New York baseball teams, the White Stockings and the Giants; August 14, 1888 was also Thayer's 25th birthday. Hopper became known as an orator of the poem, and recited it more than 10,000 times (by his count—some tabulations are as much as four times higher) before his death.[2]

"It is as perfect an epitome of our national game today as it was when every player drank his coffee from a mustache cup. There are one or more Caseys in every league, bush or big, and there is no day in the playing season that this same supreme tragedy, as stark as Aristophanes for the moment, does not befall on some field."[2]

On stage in the early 1890s, baseball star Kelly recited the original "Casey" a few dozen times and not the parody. For example, in a review of a variety show he was in, in 1893, the Indianapolis News said, "Many who attended the performance had heard of Kelly's singing and his reciting, and many had heard De Wolf Hopper recite 'Casey at the Bat' in his inimitable way. Kelly recited this in a sing-song, school-boy fashion." Upon Kelly's death, a writer would say he gained “considerable notoriety by his ludicrous rendition of 'Casey at the Bat,' with which he concluded his `turn’ [act] at each performance.”[8]

During the 1980s, the magic/comedy team Penn & Teller performed a version of "Casey at the Bat" with Teller (the "silent" partner) struggling to escape a straitjacket while suspended upside-down over a platform of sharp steel spikes. The set-up was that if Penn Jillette reached the end of the poem before Teller's escape, he would leap off his chair, releasing the rope which supported Teller, and send his partner to a gruesome death. The drama of the performance was taken up a notch after the third or fourth stanza, when Penn Jillette began to read out the rest of the poem much faster than the opening stanzas, greatly reducing the time that Teller had left to work free from his bonds.

On July 4, 2008, Jack Williams recited the poem accompanied by the Boston Pops during the annual Boston Pops Fireworks Spectacular at Boston's 4 July Celebration.

On July 14, 2013, the jam rock band Furthur performed the poem as part of a second-set medley in center field of Doubleday Field in Cooperstown, New York.[9]

Recordings

|

Casey at the Bat

Recited by DeWolf Hopper, c. 1920. |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

The first recorded version of "Casey at the Bat" was made by Russell Hunting, speaking in a broad Irish accent, in 1893; an 1898 cylinder recording of the text made for the Columbia Graphophone label by Hunting can be accessed from the Cylinder Preservation and Digitization Project at the University of California, Santa Barbara Library.

DeWolf Hopper's more famous recorded recitation was released in October 1906.

In 1946, Walt Disney released a recording of the narration of the poem by Jerry Colonna, which accompanied the studio's animated cartoon adaptation of the poem (see below).

In 1973, the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra commissioned its former Composer-in-Residence, Frank Proto, to create a work to feature Baseball Hall-of-Famer Johnny Bench with the orchestra. The result "Casey At The Bat - an American Folk Tale for Narrator and Orchestra" was an immediate hit and recorded by Bench and the orchestra. It has since been performed over 800 times by nearly every Major and Metropolitan orchestra in the U.S. and Canada.

In 1980, baseball pitcher Tug McGraw recorded Casey at The Bat by Frank Proto with Peter Nero and the Philly Pops.

In 1996, film star James Earl Jones recorded the poem with Arranger/Composer Steven Reineke and the Cincinnati Pops Orchestra.[10][11]

Mudville

A rivalry of sorts has developed between two cities claiming to be the Mudville described in the poem.

Residents of Holliston, Massachusetts, where there is a neighborhood called Mudville, claim it as the Mudville described in the poem. Thayer grew up in nearby Worcester, Massachusetts, where he wrote the poem in 1888; his family owned a woolen mill less than a mile from Mudville's baseball field.

However, residents of Stockton, California — which was known for a time as Mudville prior to incorporation in 1850—also lay claim to being the inspiration for the poem. In 1887, Thayer covered baseball for The San Francisco Examiner—owned by his Harvard classmate William Randolph Hearst—and is said to have covered the local California League team, the Stockton Ports. For the 1902 season, after the poem became popular, Stockton's team was renamed the Mudville Nine. The team reverted to the Mudville Nine moniker for the 2000 and 2001 seasons. The Visalia Rawhide, another California League team, currently keep Mudville alive by playing in Mudville jerseys on June 3 each year.[12]

Despite the towns' rival claims, Thayer himself told the Syracuse Post-Standard that "the poem has no basis in fact."[2]

Residents of Marshalltown, Iowa (home of Hall of Famer Cap Anson) often refer to their town as Mudville, though possibly for reasons of irreverence having little to do with Anson's former residency.

Adaptations

The poem has been adapted to diverse types of media, including books, film, television, music, etc. Examples include:

Books

- Ralph Andreano's 1965 book, No Joy in Mudville laments the dearth of heroes in modern baseball.

- In the book Faithful by Steward O'Nan and Stephen King, describing the 2004 season of the Boston Red Sox, there is a chapter contributed by King, named "The Gloom is gone from Mudville".

- Wallace Tripp illustrated a popular 1978 book of the poem.

- Kurtis Scaletta's 2009 children's novel, Mudville is about a town where it has been raining for 22 years, delaying a baseball game between two rival towns.

- Christopher Bing's 2000 children's book, an illustrated version of the original poem by Thayer, won a Caldecott Honor for its amazing line drawing illustrations made to look like newspaper articles from 1888.

Comics

- MAD published a Spoof in October 1960, in the 58th issue of "Mad", "'Cool' Casey at the Bat", an interpretation of the poem in beatnik style, with artwork by Don Martin.

- Marvel Comics published a Spoof in August 1969, in the 9th issue of "Not Brand Echh", featuring parodies of their popular Heroes and Villains, and the Bulk (parody of the Hulk) as Casey.

Film

- In 1922, Lee De Forest recorded DeWolf Hopper reciting the poem in DeForest's Phonofilm sound-on-film process.[13]

- In 1927, a feature-length silent film Casey at the Bat was released, starring Wallace Beery, Ford Sterling, and ZaSu Pitts—the first film adaptation of the poem.

- There have been two animated film adaptations of the poem by Walt Disney: "Casey at the Bat" (1946), which uses the original text (but set in 1902 according to the opening song's lyrics, instead of 1888). This version is recited by Jerry Colonna (as well as its sequel from 1954 called Casey Bats Again but this time not narrated by Jerry Colonna). It was later released as an individual short on July 16, 1954.

- The poem is cited in Frederic Wiseman's documentary High School (1968) by a teacher in a class room.

- In 1986, Elliott Gould starred as "Casey" in the Shelley Duvall's Tall Tales and Legends adaptation of the story, which also starred Carol Kane, Howard Cosell, Bob Uecker, Bill Macy and Rae Dawn Chong. The screenplay, adapted from the poem, was written by Andy Borowitz and the production was directed by David Steinberg.

- In The Dream Team (1989), Michael Keaton's character announces that "there is no joy in Mudville" after giving a fellow mental patient three "strikes" for psychotic behavior.

- A reference to the poem occurs in Short Cuts (1993).

- In the film What Women Want (2000), Mel Gibson's character tries to block out his daughter's thoughts by muttering the poem under his breath.

- The poem is shortly cited in the revised version of Bad News Bears.

Television

- Jackie Gleason in his "Reginald Van Gleason III" persona (in full Mudville baseball uniform) performed a recitation of the poem on his And Awaaaay We Go! album

- Season 1: Episode 35 of The Twilight Zone, "The Mighty Casey", concerns a baseball player who is actually a robot. June 17, 1960

- In the Northern Exposure episode "The Graduate" Chris Stevens gains his Masters degree in Comparative Literature by subjecting his assessors to a spirited re-enactment of the poem.

- An episode of The Simpsons entitled "Homer at the Bat" which takes its title from the poem.

- An episode of Tiny Toon Adventures features a retelling of the poem with Buster Bunny in the title role. However, instead of striking out at the end, he hits a walk off home run.

- An episode of "Animaniacs" entitled "Jokahontas/Boids on the Hood/Mighty Wakko at the Bat" includes a parody of the poem.

- An episode of "The Cleveland Show" entitled "How Cleveland Got His Groove Back" features the main character, Cleveland Brown, striking out in a game. The following scene cuts to a storybook featuring the lines "But there is no joy in Stoolbend, mighty Cleveland has struck out," a play on the last line of the poem.

- An episode of the television series The Adventures of Jimmy Neutron: Boy Genius entitled "Return of the Nanobots" has Cindy Vortex reciting a poem that ends with the lines "But there is no joy in Retroville, 'cause Jimmy is an idiot."

- In the fourth season of "Garfield and Friends" the episode entitled "Mind Over Matter/Orson at the Bat/Multiple Choice Cartoon" features Wade Duck narrating a parody of the poem as Orson Pig experiences it in a dream sequence.

- A third-season episode of American television show Storm Chasers was titled "Sean Casey At Bat". The episode featured Casey (a chaser) intercepting a tornado for the first time in TIV 2.

- In How I Met Your Mother, the episode Bedtime Stories (which is done entirely in rhymes) features a subplot called "Mosby At The Bat". The subplot consists of Ted, the main character, going on a date with a girl, who reveals that she once dated a New York Yankee. However, when Ted asks, it turns out that the player was just his friend Barney. The start of that section of the episode begins with "The outlook wasn't brilliant for poor Ted's romantic life", a line based on the opening of the original poem.[14]

Music

- Art-song composer Sidney Homer turned the poem into a song. Sheet music was published by G. Schirmer in 1920 as part of Six Cheerful Songs to Poems of American Humor.

- William Schuman composed an opera, The Mighty Casey (1953), based on the poem.

- The song No Joy in Mudville from Death Cab for Cutie's album We Have the Facts and We're Voting Yes directly references the poem.

- The song "Rocky Mountain Way" by Joe Walsh includes the line, "The bases are loaded and Casey's at bat, playing it play by play. Time to change the batter."

- The song "Felicia" on the Straight On till Morning album by Blues Traveler includes the line "I wouldn't feel so much like Casey who never got to bat."

- The song "Centerfield" by John Fogerty includes the line "Well, I spent some time in the Mudville Nine, watchin' it from the bench. You know I took some lumps when the Mighty Case struck out."

- The song "To the Dogs or Whoever" by Josh Ritter includes the stanza "Was it Casey Jones or Casey at the Bat who died out of pride and got famous for that? Killed by a swerve, laid low by the curve, do you ever think they ever thought they got what they deserved?"

- The song "No Joy In Pudville" by Steroid Maximus is a reference to this poem.

- Randol Alan Bass composed Casey at the Bat for the Dallas Symphony Orchestra. At the premier in April 2001, Pat Sajak was the narrator.[15]

- Columbus, Ohio based pop/rock band Casey At The Bat, formed in 2012.

Theatre

- "Casey at the Bat" was adapted into a 1953 opera by American composer William Schuman. Allen Feinstein composed an adaptation for orchestra with a narrator. An orchestral version was composed by Stephen Simon in 1976 for the bicentennial; Maestro Classics' has recorded it with the London Philharmonic Orchestra, Stephen Simon conducting with Yadu (Dr. Konrad Czynski) narrating. An orchestral adaptation by composer Frank Proto has been recorded by the Cincinnati Pops orchestra conducted by Erich Kunzel with baseball star Johnny Bench narrating. The Dallas Symphony commissioned an arrangement of "Casey" by Randol Alan Bass in 2001 which he later arranged for concert band. A version for wind band and narrator by Donald Shirer based on "Take Me Out to the Ball Game" had its world premiere in July 2008.

- The last verse of the poem is quoted in the musical Cabaret – Cliff recites it to Sally when they first meet.

Derivations

For a relatively short poem apparently dashed off quickly (and denied by its author for years), "Casey at the Bat" had a profound effect on American popular culture. It has been recited, re-enacted, adapted, dissected, parodied and subjected to just about every other treatment one could imagine.[2]

Sequels

"Casey's Revenge", by Grantland Rice (1907), gives Casey another chance against the pitcher who had struck him out in the original story. It was written in 1906, and its first known publication was in the quarterly magazine The Speaker in June 1907, under the pseudonym of James Wilson.[16] In this version, Rice cites the nickname "Strike-Out Casey", hence the influence on Casey Stengel's name. Casey's team is down three runs by the last of the ninth, and once again Casey is down to two strikes—with the bases full this time. However, he connects, hits the ball so far that it is never found. Here is the original version of the poem:

- There were saddened hearts in Mudville for a week or even more;

- There were muttered oaths and curses- every fan in town was sore.

- "Just think," said one, "how soft it looked with Casey at the bat,

- And then to think he'd go and spring a bush league trick like that!"

- All his past fame was forgotten- he was now a hopeless "shine."

- They called him "Strike-Out Casey," from the mayor down the line;

- And as he came to bat each day his bosom heaved a sigh,

- While a look of hopeless fury shone in mighty Casey's eye.

- He pondered in the days gone by that he had been their king,

- That when he strolled up to the plate they made the welkin ring;

- But now his nerve had vanished, for when he heard them hoot

- He "fanned" or "popped out" daily, like some minor league recruit.

- He soon began to sulk and loaf, his batting eye went lame;

- No home runs on the score card now were chalked against his name;

- The fans without exception gave the manager no peace,

- For one and all kept clamoring for Casey's quick release.

- The Mudville squad began to slump, the team was in the air;

- Their playing went from bad to worse – nobody seemed to care.

- "Back to the woods with Casey!" was the cry from Rooters' Row.

- "Get some one who can hit the ball, and let that big dub go!"

- The lane is long, some one has said, that never turns again,

- And Fate, though fickle, often gives another chance to men;

- And Casey smiled; his rugged face no longer wore a frown-

- The pitcher who had started all the trouble came to town.

- All Mudville had assembled – ten thousand fans had come

- To see the twirler who had put big Casey on the bum;

- And when he stepped into the box, the multitude went wild;

- He doffed his cap in proud disdain, but Casey only smiled.

- "Play ball!" the umpire's voice rang out, and then the game began.

- But in that throng of thousands there was not a single fan

- Who thought that Mudville had a chance, and with the setting sun

- Their hopes sank low- the rival team was leading "four to one."

- The last half of the ninth came round, with no change in the score;

- But when the first man up hit safe, the crowd began to roar;

- The din increased, the echo of ten thousand shouts was heard

- When the pitcher hit the second and gave "four balls" to the third.

- Three men on base – nobody out – three runs to tie the game!

- A triple meant the highest niche in Mudville's hall of fame;

- But here the rally ended and the gloom was deep as night,

- When the fourth one "fouled to catcher" and the fifth "flew out to right."

- A dismal groan in chorus came; a scowl was on each face

- When Casey walked up, bat in hand, and slowly took his place;

- His bloodshot eyes in fury gleamed, his teeth were clenched in hate;

- He gave his cap a vicious hook and pounded on the plate.

- But fame is fleeting as the wind and glory fades away;

- There were no wild and woolly cheers, no glad acclaim this day;

- They hissed and groaned and hooted as they clamored: "Strike him out!"

- But Casey gave no outward sign that he had heard this shout.

- The pitcher smiled and cut one loose – across the plate it sped;

- Another hiss, another groan. "Strike one!" the umpire said.

- Zip! Like a shot the second curve broke just below the knee.

- "Strike two!" the umpire roared aloud; but Casey made no plea.

- No roasting for the umpire now – his was an easy lot;

- But here the pitcher whirled again- was that a rifle shot?

- A whack, a crack, and out through the space the leather pellet flew,

- A blot against the distant sky, a speck against the blue.

- Above the fence in center field in rapid whirling flight

- The sphere sailed on – the blot grew dim and then was lost to sight.

- Ten thousand hats were thrown in air, ten thousand threw a fit,

- But no one ever found the ball that mighty Casey hit.

- O, somewhere in this favored land dark clouds may hide the sun,

- And somewhere bands no longer play and children have no fun!

- And somewhere over blighted lives there hangs a heavy pall,

- But Mudville hearts are happy now, for Casey hit the ball.

In response to the popularity of the 1946 Walt Disney animated adaptation, Disney made a sequel, "Casey Bats Again" (1954), in which Casey's nine daughters redeem his reputation.

In 1988, on the 100th anniversary of the poem, Sports Illustrated writer Frank Deford constructed a fanciful story (later expanded to book form) which posited Katie Casey, the subject of the song "Take Me Out to the Ball Game", as being the daughter of the famous slugger from the poem.

In 2010, Ken Eagle wrote “The Mudville Faithful,” covering a century of the Mudville nine's ups and downs since Casey struck out. Faithful fans still root for the perpetually losing team, and are finally rewarded by a trip to the World Series, led by Casey's great-grandson who is also named Casey.

Parodies

Of the many parodies made of the poem, some of the notable ones include:

- Mad republished the original version of the poem in the 1950s with artwork by Jack Davis and no alterations to the text. Later lampoons in Mad included "'Cool' Casey at the Bat" (1960), an interpretation of the poem in beatnik style, with artwork by Don Martin; "Casey at the Dice" in 1969, about a professional gambler; "Casey at the Talks" in 1977, a "modern" version of the famed poem in which Mudville tries unsuccessfully to sign free agent Casey[the last line of which is "Mighty Casey has held out"]; "Baseball at the Bat", a satire on baseball itself, "Howard at the Mike," about Howard Stern; "Casey at the Byte" (1985), a tale of a cocky young computer expert who accidentally erases the White House Budget Plan; "Clooney as the Bat", a mockery of George Clooney's role as Batman in Batman and Robin; and in 2006 as "Barry at the Bat", poking fun at Barry Bonds' alleged involvement in the BALCO scandal, and in 2001, "Jordan at the Hoop", satirizing Michael Jordan's return to the NBA and his time with the Washington Wizards. Another parody takes place in Russia, which ends with "Kasey" in a gulag prison. A "Poetry Round Robin" where famous poems are rewritten in the style of the next poet in line, featured Casey at the Bat as written by Edgar Allan Poe.

- Foster Brooks ("the Lovable Lush") wrote "Riley on the Mound", which recounts the story from the pitcher's perspective.

- Radio performer Garrison Keillor's parodic version of the poem[17] reimagines the game as a road game, instead of a home game, for the Mudville team. The same events occur with Casey striking out in the ninth inning as in the original poem, but with everything told from the perspective of other team.

- An episode of Tiny Toon Adventures featured a short titled "Buster at the Bat", where Sylvester provides narration as Buster goes up to bat. The poem was parodied again for an episode of Animaniacs, this time with Wakko as the title character and Yakko narrating.

- In the Adventures of Jimmy Neutron: Boy Genius episode "The Return of the Nanobots", Cindy's poem is identical to the ending of "Casey at the Bat" but replaces Mudville with Retroville and the last famed line with "cause Jimmy is an idiot!"

- An episode of the show U.S. Acres was titled "Orson at the Bat".

- The New York Times published a parody by Hart Seely and Frank Cammuso in which the poem was narrated by Phil Rizzuto, a New York Yankees announcer who was known to veer off on tangents while calling the game. The poem was later published in Seely and Cammuso's book, 2007 Eleven And Other American Comedies.

- Issue #92 of the comic Fables employs a paraphrased version of "Casey at the Bat" appropriating the character names to those of the Fable players. It is preceded by a mock apology to Ernest Thayer for the mangling of "his beloved poem".

- David Pogue penned a parody version titled 'A Desktop Critic: Steven Saves the Mac' for Macworld magazine that ran in their October 1999 issue.[18] It tells the story of Steve Jobs' triumphant return to a struggling Apple Inc and his early efforts to reverse the company's fortunes.

- Dick Flavin wrote a version titled Teddy at the Bat, after Boston Red Sox legend Ted Williams died in July, 2002. Flavin performed the poem at Fenway Park during the night-long tribute to Williams done at the park later that month. The poem replaced Flynn and Blake with Bobby Doerr and Johnny Pesky, the batters who preceded Williams in the 1946 Red Sox lineup.

- In 2000, Michael J. Farrand adapted the rhyming scheme, tone, and theme of the poem—while reversing the outcome—to create his poem "The Man Who Gave All the Dreamers in Baseball Land Bigger Dreams to Dream" about Kirk Gibson's home run off Dennis Eckersley in Game 1 of the 1988 World Series. The poem appears at the Baseball Almanac.

Translations

There are three known translations of the poem into a foreign language, one in French, written in 2007 by French Canadian linguist Paul Laurendeau, with the title Casey au bâton, and two in Hebrew. One by the sports journalist Menachem Less titled "התור של קייסי לחבוט" [Hator Shel Casey Lachbot],[19] and the other more recent and more true to the original cadence and style by Jason H. Elbaum called קֵיסִי בַּמַּחְבֵּט [Casey BaMachbayt].[20]

Names

Casey Stengel describes, on page 11 of his autobiography Casey at the Bat: The Story of My Life in Baseball (Random House, 1962), how his nickname of "K.C." (for his hometown, Kansas City, Missouri) evolved into "Casey". It was influenced not just by the name of the poem, which was widely popular in the 1910s, but also because he tended to strike out frequently in his early career so fans and writers started calling him "strikeout Casey".

Contemporary Culture

Games

The poem is referenced in the Super Nintendo Entertainment System game EarthBound, where a weapon is named the Casey Bat, which is the strongest weapon in the game, but will only hit 25% of the time.

Theme parks

- Casey's Corner is a baseball-themed restaurant in Walt Disney World's Magic Kingdom, which serves primarily hotdogs. Pictures of Casey and the pitcher from the Disney animated adaptation are hanging on the walls, and a life-size statue of a baseball player identified as "Casey" stands just outside the restaurant. Additionally, the scoreboard in the restaurant shows that Mudville lost to the visitors by two runs.

- A hot dog restaurant featuring the Disney character can be found at Disneyland Paris since its opening in 1992, under the name Casey's Corner.

- A game called Casey at the Bat is in the Games of the Boardwalk at the Disneyland Resort's Disney California Adventure.

Postage stamp

On July 11, 1996, the United States Postal Service issued a commemorative stamp depicting "Mighty Casey." The stamp was part of a set commemorating American folk heroes. Other stamps in the set depicted Paul Bunyan, John Henry, and Pecos Bill.

References

- ↑ Baseball Almanac

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Gardner, Martin (October 1967). "Casey At The Bat". American Heritage 18 (6). Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- ↑ Rosenberg, Howard W. (2004). Cap Anson 2: The Theatrical and Kingly Mike Kelly: U.S. Team Sport's First Media Sensation and Baseball's Original Casey at the Bat. Tile Books. p. 438. ISBN 0-9725574-1-5., p. 121-122.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Rosenberg. Cap Anson 2., p. 9.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Rosenberg. Cap Anson 2., p. 2.

- ↑ "Ernest Lawrence Thayer and "Casey at the Bat"". Joslin Hall Rare Books News List. Retrieved June 2, 2009.

- ↑ Rosenberg. Cap Anson 2., p. 9, citing Current Literature 21 (January 1897): 96, which, in part, referred to "T. J. M." to Current Literature, undated, in Current Literature 20 (December 1896): 576; Current Literature 21 (February 1897): 129; and Jim Moore and Natalie Vermilyea, Ernest Thayer's 'Casey at the Bat': Background and Characters of Baseball's Most Famous Poem (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 1994), pp. 2, 234, 235 and 240.

- ↑ Rosenberg. Cap Anson 2., p. 229.

- ↑ https://archive.org/details/furthur2013-07-14.AKGc1000s

- ↑ "Casey At The Bat". Casey at the Bat – James Earl Jones. YouTube. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ↑ 1998 CD: Play Ball! – Erich Kunzel – Cincinnati Pops Orchestra, Recorded 1996 with Arranger/Composer Steven Reineke and the Cincinnati Pops Orchestra (insert credits) – http://www.amazon.com/dp/B0000064U5

- ↑ baseball-reference.com, accessed June 7, 2008

- ↑ SilentEra entry with photo of Hopper

- ↑ "How I Met Your Mother Episode Bedtime Stories Scripts". springfieldspringfield.co.uk. Retrieved 7 December 2014.

- ↑ "Randol Alan Bass – Casey at the Bat".

- ↑ Gardner, Martin (1995). The Annotated Casey at the Bat: A Collection of Ballads About the Mighty Casey. Dover Publications. p. 38. ISBN 0-486-28598-7.

- ↑ Casey at the Bat (Road Game) by Garrison Keillor on Baseball Almanac

- ↑ Pogue, David. "The Desktop Critic: Steven Saves the Mac", "Macworld", October, 1999, accessed May 30, 2011.

- ↑ הספורט הגדולה מכולן!

- ↑ Casey at the Bat – in Hebrew

Sources

- Gardner, Martin, "The Annotated Casey at the Bat: A Collection of Ballads about the Mighty Casey", New York: Clarkson Potter. 1967 (Revised edition: Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984 [ISBN 0-226-28263-5]; 3rd edition: New York: Dover, 1995 [ISBN 0-486-28598-7]).

- Rosenberg, Howard W, "Cap Anson 2: The Theatrical and Kingly Mike Kelly: U.S. Team Sport's First Media Sensation and Baseball's Original Casey at the Bat", Arlington, VA: Tile Books, 2004 [ISBN 0-9725574-1-5]

- "Mudville Journal; In 'Casey' Rhubarb, 2 Cities Cry 'Foul!'" by Katie Zezima, The New York Times, March 31, 2004.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- "Casey at the Bat" on MLB.com.

- Hear Hopper recite the poem.

- Library of Congress essay on its inclusion into the National Recording Registry.

- Casey at the Bat cylinder recording by Russell Hunting, from the Cylinder Preservation and Digitization Project at the University of California, Santa Barbara Library.

- "Casey at the Bat" Web site with biographical details on Thayer, Hopper, Mike "King" Kelly and chronology of the poem's publication.

- "Casey at the Bat" as told in baseball cards

- Poems about Casey's later life, including another by Grantland Rice, and one by Garrison Keillor