Case analysis

Case analysis is one of the most general and applicable methods of analytical thinking, depending only on the division of a problem, decision or situation into a sufficient number of separate cases. Analysing each such case individually may be enough to resolve the initial question. The principle of case analysis is invoked in the celebrated remark of Sherlock Holmes, to the effect that when one has eliminated the impossible, what remains must be true, however unlikely it seems.

The logical roots of the Holmes remark speak to the principle of excluded middle. That indicates the importance to case analysis of logical disjunction: stringing together propositions with the logical connective "or". Medical diagnosis can indeed follow the Holmes pattern, with a patient's symptom possibly caused by a number of conditions: the patient suffers from A or B or ... or illness I; see differential diagnosis. Deductive logic is applied to reducing the number of cases; see case-based reasoning.

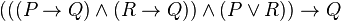

A canonical statement of case analysis in the sentential calculus is this:

"If a statement P implies a statement Q, and a statement R also implies Q, and either P or R is true, then Q must be true."

Exhaustive analysis

The most important issue in this style of case analysis is that the cases should be collectively exhaustive: everything is covered. The condition that they should be exclusive, while convenient, is not to be assumed lightly; for example a patient's liver problem might be caused by hepatitis and abuse of alcohol, with one factor not ruling out the other. This points up the distinction between exclusive or, and logical disjunction which is the default meaning of 'or' (in logic, mathematics and science) and which is non-exclusive. Case analysis of the non-overlapping kind is a special case, only.

That being said, in computer programming, case analysis presents itself in a form best adapted to exclusive cases. In simple terms, the requirement is to have a list of actions, so that 'if X = 1 do P, if X = 2 do Q, if X = 3 do R' can be given as quite unambiguous instructions. The value of X here is computed according to what case one is in.

Other terminology

Case-by-case analysis is a more specific term for such a pinning-down of cases. It assumes a situation in which a thorough-going case analysis can be completed: all cases covered and resolved. This is not always realistic. Other forms of case analysis are best case analysis and worst case analysis, scenarios for the optimist and pessimist, respectively.

Two names for approaches that take complete case-by-case analysis as not meeting the needs of the topic under consideration are casuistry, most often in ethics, and the case study method used in business schools.

See also

- Mutually exclusive

- Collectively exhaustive

- Pattern matching

- Proof by exhaustion