Carlson's theorem

- Not to be confused with Carleson's theorem

In mathematics, in the area of complex analysis, Carlson's theorem is a uniqueness theorem which was discovered by Fritz David Carlson. Informally, it states that two different analytic functions which do not grow very fast at infinity can not coincide at the integers. The theorem may be obtained from the Phragmén–Lindelöf theorem, which is itself an extension of the maximum-modulus theorem.

Carlson's theorem is typically invoked to defend the uniqueness of a Newton series expansion. Carlson's theorem has generalized analogues for other expansions.

Statement of theorem

Assume that f satisfies the following three conditions: the first two conditions bound the growth of f at infinity, whereas the third one states that f vanishes on the non-negative integers.

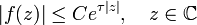

- f(z) is an entire function of exponential type, meaning that

- for some C, τ < ∞

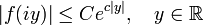

- There exists c < π such that

- f(n) = 0 for any non-negative integer n.

Then f is identically zero.

Sharpness

First condition

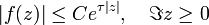

The first condition may be relaxed: it is enough to assume that f is analytic in Re z > 0, continuous in Re z ≥ 0, and satisfies

for some C,τ < ∞

Second condition

To see that the second condition is sharp, consider the function f(z) = sin(πz). It vanishes on the integers; however, it grows exponentially on the imaginary axis with a growth rate of c = π, and indeed it is not identically zero.

Third condition

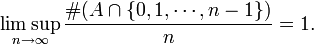

A result, due to Rubel (1956), relaxes the condition that f vanish on the integers. Namely, Rubel showed that the conclusion of the theorem remains valid if f vanishes on a subset A ⊂ {0,1,2,...} of upper density 1, meaning that

This condition is sharp, meaning that the theorem fails for sets A of upper density smaller than 1.

Applications

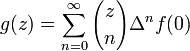

Suppose f(z) is a function that possess all finite forward differences  . Consider then the Newton series

. Consider then the Newton series

with  is the binomial coefficient and

is the binomial coefficient and  is the n 'th forward difference. By construction, one then has that f(k)=g(k) for all non-negative integers k, so that the difference h(k)=f(k)-g(k)=0. This is one of the conditions of Carlson's theorem; if h obeys the others, then h is identically zero, and the finite differences for f uniquely determine its Newton series. That is, if a Newton series for f exists, and the difference satisfies the Carlson conditions, then f is unique.

is the n 'th forward difference. By construction, one then has that f(k)=g(k) for all non-negative integers k, so that the difference h(k)=f(k)-g(k)=0. This is one of the conditions of Carlson's theorem; if h obeys the others, then h is identically zero, and the finite differences for f uniquely determine its Newton series. That is, if a Newton series for f exists, and the difference satisfies the Carlson conditions, then f is unique.

See also

- Newton series

- Table of Newtonian series

References

- F. Carlson, Sur une classe de séries de Taylor, (1914) Dissertation, Uppsala, Sweden, 1914.

- M. Riesz, "Sur le principe de Phragmén–Lindelöf", Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 20 (1920) 205–107, cor 21(1921) p. 6.

- G.H. Hardy, "On two theorems of F. Carlson and S. Wigert", Acta Mathematica, 42 (1920) 327–339.

- E.C. Titchmarsh, The Theory of Functions (2nd Ed) (1939) Oxford University Press (See section 5.81)

- R. P. Boas, Jr., Entire functions, (1954) Academic Press, New York.

- R. DeMar, "Existence of interpolating functions of exponential type", Trans. Amer. Math. Soc., 105 (1962) 359–371.

- R. DeMar, "Vanishing Central Differences", Proc. Amer. math. Soc. 14 (1963) 64–67.

- Rubel, L. A. (1956), "Necessary and sufficient conditions for Carlson's theorem on entire functions", Trans. Amer. Math. Soc. 83: 417–429, doi:10.1090/s0002-9947-1956-0081944-8, JSTOR 1992882, MR 0081944