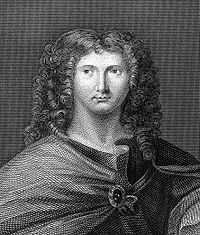

Carey Dillon, 5th Earl of Roscommon

Carey or Cary Dillon, 5th Earl of Roscommon (1627-1689) was an Irish nobleman and professional soldier of the seventeenth century. He held several Court offices under King Charles II and his successor King James II but after the Glorious Revolution went over to the Williamite side, and was attainted as a traitor by James II's Irish Parliament in 1689, shortly before his death. He was a friend of Samuel Pepys, who in the great Diary followed with interest Dillon's abortive love affair with a mutual friend, the celebrated beauty Frances Butler.[1]

Background

He was a younger son of Robert Dillon, 2nd Earl of Roscommon (died 1642), by his third wife Anne Strode, daughter of Sir William Strode of Somerset.[2] His mother, who died about 1650, was the widow of Henry Folliott, 1st Baron Folliott, by whom she had several children. As a younger son in the war-torn Ireland of the 1640s and 1650s, a military career was an obvious choice for him: he was a Captain by the age of seventeen. Although Pepys always called him "Colonel Dillon" he was apparently only a Lieutenant until 1684, when he became Major and subsequently Colonel. His father in the 1630s had been a supporter of Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Strafford, the Lord Deputy of Ireland, as was his half-brother James Dillon, 3rd Earl of Roscommon, and a family tie was created when James married Strafford's sister Elizabeth.[3] During the English Civil War, both brothers were staunch Royalists: James, who died in 1649, was posthumously listed in the Act for the Settlement of Ireland 1652 as one of the ten leaders of the Royalist cause in Ireland, and thus liable to forfeiture of his estates.

Duel

Following the Restoration of Charles II, Dillon entered politics, sitting in the Irish House of Commons as MP for Banagher in the Parliament of 1661-1666.[4] His career was almost ruined in 1662 when he acted as second to Colonel Thomas Howard in his notorious duel with Henry Jermyn, 1st Baron Dover (Howard and Dover being rivals for the affections of Anna Talbot, Countess of Shrewsbury). Howard left Lord Dover for dead, and Dillon killed Dover's second, Giles Rawlings.[5] He and Howard initially fled, but later returned to stand their trials, and as was usual at the time in an affair of honour, they were both acquitted, as killing a man in a duel was generally regarded as self-defence.

Political Career

Any check to his career was temporary, and after 1670 his rise in Irish politics was rapid. He was sworn a member of the Privy Council of Ireland in 1673, and also became Master of the Irish Mint, Commissary-General of the Horse of Ireland, Surveyor-General for Customs and Excise in Ireland, and a Governor of the Royal Hospital Kilmainham.[6] In 1685, on the death of his nephew, the poet Wentworth Dillon, 4th Earl of Roscommon, he succeeded to the Earldom.[7]

Williamite

Having served the Stuart dynasty with seeming loyalty both during the Civil War and after the Restoration, Lord Roscommon abruptly changed sides after the downfall and flight to France of James II in 1688. While James attempted to reconquer England by occupying Ireland, Roscommon offered his services to King William III of England. He was commissioned to raise troops on William's behalf, and was present at the taking of Carrickfergus, the crucial first step in William's campaign to wrest control of Ireland from James's invading army, in August 1689. In consequence he was attainted by King James II's Patriot Parliament held in Dublin in the summer of 1689. He died the following November.[8]

Family

He married Katherine Werden (died 1683), daughter of John Werden of Chester, by whom he had a son and heir, Robert Dillon, 6th Earl of Roscommon (died 1715), who is said still to have been a young child when his father died.[9] The 5th Earl also had two daughters, Anne, who married Sir Thomas Nugent in about 1675, and Catherine (died 1674), who married Hugh Montgomery, 2nd Earl of Mount Alexander. The sisters were so many years older than their brother that it is possible they were children of an earlier marriage: if so, their mother must have died before 1660, since it is clear from the Diary of Samuel Pepys that Dillon was free to marry between 1660 and 1668.

In Pepys's Diary

Pepys evidently liked Dillon, whom he first seems to have met in 1660, calling him "a very merry and witty companion".[10] At the start of the Diary period one of Pepys's closest friends was a young clergyman called Butler (nicknamed "Monsieur l'Impertinent", apparently because he never stopped talking), who was probably, like Dillon, an Irishman.[11] Pepys admired both of Butler's sisters, especially Frances ("la belle Boteler"), whom he thought one of the greatest beauties in London. Dillon courted Frances, and matters proceeded as far as an engagement, but this was broken off in 1662, apparently after a violent quarrel between Dillon and Frances's brother "Monsiuer l'Impertinent", who complained of Dillon's "knavery" to him.[12] In the summer of 1668 Dillon apparently renewed his proposal of marriage- Pepys saw him and Frances riding in a carriage together- but was clearly not successful. It is not known whether Frances ever married.[13]

References

- ↑ Diary of Samuel Pepys 28 July 1660

- ↑ Burke Extinct Peerages Reprinted Baltimore 1978 p.172

- ↑ Wedgwood, C.V. "Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Strafford 1593-1641- a Revaluation" Phoenix Press reissue 2000 p.324

- ↑ Latham, Robert and Matthews, William The Diary of Samuel Pepys Bell and Hyman 1983 Vol. X Companion p. 92

- ↑ Pepys's Diary 19 August 1660

- ↑ Pepys's Diary Companion p.92

- ↑ Pepys's Diary Companion p.92

- ↑ Journal of John Stevens, containing a brief account of the war in Ireland 1689-1691 Folio 75A p.110

- ↑ Burke Extinct Peerages p.172

- ↑ Pepys's Diary 8 August 1660

- ↑ Bryant, Arthur Samuel Pepys- the Man in the Making Reprint Society London 1952 p.65. Bryant thought that he was an impoverished member of the Butler dynasty.

- ↑ Pepys's Diary 31 December 1662

- ↑ Pepys's Diary 20 September 1668