Carboniferous Limestone

The Carboniferous Limestone is a collective term for the succession of limestones occurring widely throughout Great Britain and Ireland that were deposited during the Dinantian Epoch of the Carboniferous Period. These rocks formed between 363 and 325 million years ago. Within England and Wales, the entire limestone succession, which includes subordinate mudstones and some thin sandstones, is known as the Carboniferous Limestone Supergroup.

Depositional basins

Within Great Britain the suite of rocks known traditionally as the Carboniferous Limestone Series was deposited as marine sediments in three distinct ‘provinces’ separated by contemporary landmasses. One of these landmasses was the Wales-London-Brabant Massif, an east-west aligned belt of land stretching through central Wales and the English Midlands to East Anglia and on into Belgium. The limestones deposited to its south form a distinct South Wales-Mendip province which extends from Pembrokeshire in the west through southern Carmarthenshire, Glamorgan and south Powys to Monmouthshire, Gloucestershire and north Somerset. These rocks continue eastwards at depth beneath Oxfordshire. The Carboniferous Limestone sequence of South Wales and the Bristol area is currently (2012) subdivided thus:

- Pembroke Limestone Group (uppermost/youngest)

- Oystermouth Formation

- Oxwich Head Limestone Formation

- Penderyn Oolite Member

- Honeycombed Sandstone Member

- Dowlais Limestone Formation

- Abercriban Oolite Subgroup & Clydach Valley Subgroup

- Avon Group

- Cwmyniscoy Mudstone Formation

- Castell Coch Limestone Formation (lowermost/oldest)

The limestone found north of the Wales-London-Brabant Massif and south of the emergent Southern Uplands block is identified as a separate northern province. It is characterised by the presence of numerous ‘blocks’ and ‘basins’ each with its own particular depositional style.

To the north of the Southern Uplands are the limestones of the Scottish Midland Valley stretching from Ayrshire and Arran in the west to Fife, Lothian and Berwickshire in the east. Though of Carboniferous age, the limestones of this Scottish province are not assigned to the Carboniferous Limestone Supergroup.[1]

The Carboniferous Limestone is widespread throughout Ireland.

Geographical extent

The Carboniferous Limestone is a significant landscape-forming rock unit in each of the depositional provinces of Great Britain within which it is found.

South Wales and Bristol area

Within Pembrokeshire the Carboniferous Limestone forms the spectacular coastal cliffs at St Govan’s Head along from which are features such as Huntsman's Leap and the Green Bridge of Wales, a natural arch. It forms prominent headlands such as those of Stackpole Head and Lydstep Point and the cliffs at Tenby .[2] A narrow, intensely quarried outcrop runs inland from Carmarthen Bay through Carmarthenshire from Kidwelly, entering the Brecon Beacons National Park at Llandyfan and extending westwards through the Black Mountain to Cribarth above the upper Swansea Valley . It is here referred to as the ‘north crop’ as distinct from a sub-parallel outcrop, the ‘south crop’ which defines the southern rim of the South Wales Coalfield. The outcrop continues through Ystradfellte to Pontneddfechan, Penderyn and Pontsticill.[3] It then runs near the southern margin of the national park via Trefil and the Llangattock escarpment to Blorenge where it turns southwards. A very narrow ‘east crop’ and ‘south crop’ run by Cwmbran and north of Cardiff.[4] It turns west again to meet Swansea Bay at Porthcawl. West of the bay, the rock forms the renowned southern coast of Gower between Mumbles Head and Worms Head .[5] There are further occurrences in the Vale of Glamorgan, both inland and on the coast.[6]

An important outlier is that of the Forest of Dean basin which forms the cliffs of the Wye Valley, straddling the England/Wales border and extends southwestwards through Chepstow to Undy.

The larger part of the Mendip Hills are formed from Carboniferous Limestone, showing notable geomorphological features, including Cheddar Gorge, Burrington Combe and the showcave of Wookey Hole. The Avon Gorge west of Bristol and the coastal cliffs at Clevedon and Weston-super-Mare are cut in this rock. The limestone islands of Flat Holm and Steep Holm are prominent in views across the mouth of the Severn Estuary.

The Northern Province

There are limited outcrops on the Isle of Man[7] and more extensive ones in Anglesey notably along the Menai Strait, around Benllech and towards Puffin Island.[8] The Carboniferous Limestone belt extends eastwards to from the Great Orme at Llandudno, the neighbouring Little Orme and a zone of country in inland Denbighshire running through Denbigh and Ruthin. A broader belt forms high ground immediately east of the Clwydian Hills extending south to form the impressive west-facing Eglwyseg escarpment north of Llangollen and continuing as a broken outcrop southwards beyond Oswestry.[9] There are a few outcrops in Shropshire such as Titterstone Clee Hill and at Little Wenlock.

The White Peak is named for the limestone which characterises the heart of the Peak District and through which deep gorges have been cut by rivers such as the Wye, Dove and Manifold.[10] The limestone is concealed beneath younger rocks to the east and west and to the north through the South Pennines.

To the north the limestone is exposed once again in east Lancashire and in the Yorkshire Dales.[11] There are numerous limestone hills in the Arnside and Silverdale AONB and in the southern Lake District e.g. Whitbarrow Scar with coastal exposures around the northern margins of Morecambe Bay such as Humphrey Head.[12] An outcrop extends from Kirkby Stephen along the western side of the Vale of Eden and wraps around the northern margin of the Lake District as far as Cleator Moor.[13]

North again, it is a major landscape forming feature in the North Pennines and thence through Northumberland to the Northumberland Coast where it extends to the Scottish border at Berwick-upon-Tweed. There are scattered outcrops along the north coast of the Solway Firth.

Midland Valley of Scotland

Limestones occur in southern Ayrshire and in a very broken band running northeastwards through the Pentland Hills towards Edinburgh. There are limited outcrops on the coasts of East Lothian and Berwickshire, isolated outcrops in Fife and Stirlingshire and further occurrences around Greenock and Dumbarton.[14]

Ireland

Carboniferous Limestone occurs most famously around The Burren in County Clare, western Ireland where it produces one of western Europe's most important karst landscapes.

Characteristics

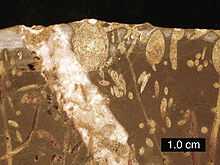

Carboniferous Limestone is a sedimentary rock made of calcium carbonate. It is generally light-grey in colour, and is hard. It was formed in warm, shallow tropical seas teeming with life. The rock is made up of the shells and hard parts of millions of sea creatures, some up to 30 cm in length, encased in carbonate mud. Fossil corals, brachiopods and crinoids are very much in evidence as components of Carboniferous Limestone; indeed the rock is full of fossils.

Carboniferous Limestone has horizontal layers (beds) with bedding planes, and vertical joints. These joints are weaknesses in the rock, which are exploited by agents of both denudation and weathering. They also lead to the most important characteristic of Carboniferous Limestone – its permeability. Water seeps through the joints in the limestone. This creates a landscape geologists call karst, which lacks surface drainage but which has all manner of characteristic surface and subsurface features. The Carboniferous Limestone has been folded and faulted by massive Earth movements which can be seen by the fact that the rocks are now above sea-level and no longer horizontal. The rocks generally dip (slope) gently eastwards and, in some places, clear folds in the rock can be seen especially at the Great Orme and Bryn Alyn (Denbighshire).

Surface features

The 'classic limestone walk' is a circular 10 km route from the field centre on the north side of Malham Tarn to the village of Malham, UK via Watlowes Valley and back again via Gordale Scar.

Small surface depressions called shakeholes, which are 1–3 m deep and 3–5 m across, form as a result of the subsurface collapse of limestone. Shakeholes are very common throughout the Yorkshire Dales. Larger depressions are called dolines.

Streams flowing from higher impermeable slopes sink into the ground when they reach permeable limestone. During dry spells all water sinks very quickly on reaching the limestone, through sinkholes. In wetter conditions water flows a greater distance across the limestone as underground channels and chambers fill up. Large sinkholes are called 'swallowholes' or 'potholes'. Gaping Gill, Alum Pot and the Buttertubs are well-known examples.

Dry valleys are valleys without streams. Watlowes Valley is an excellent example. It was formed originally by a subglacial meltwater stream which existed during the last major Ice Age. After the ice retreated, the valley was further developed by a meltwater stream flowing across the limestone while it was frozen solid. Watlowes Valley is a particularly good example of a dry valley because it has a textbook profile - the south-facing side is less steep than the north-facing side. This results from the weathering and mass movement processes that have operated in the post-glacial period.

A limestone pavement is an area of almost bare, flat rock and is arguably the most fascinating feature of any area of carboniferous limestone. They develop after the rock has been exposed by the scouring action of an ice sheet or glacier. Existing joints are subsequently exploited by the action of chemical weathering carbonation to form deep grykes and rounded blocks called clints. Grykes have a habitat of their own, which encourages the growth of shade-loving ferns such as hart's tongue and dog's mercury. During the last Ice Age, a stream is thought to have poured over Malham Cove - the most spectacular feature in the Yorkshire Dales. At the end of the Ice Age the limestone, which had been frozen solid, once again became permeable, allowing the water to disappear through its joints. Now Malham Cove is a high cliff (83 m high) – it is completely dry, and a great attraction to rock climbers.

A gorge is a steep-sided valley, often formed in a limestone area as the result of the collapse of a roof above a cave system. Gordale Scar is an excellent example.

Subsurface features

Caves are common subsurface features in limestone landscapes. In the Yorkshire Dales, there are numerous caves, three of which – Ingleborough Cave, White Scar Caves and Stump Cross Caverns – are now show caves for the public.

In Ireland there is a large amount of show caves open to visitors - Crag Cave, Ailwee Cave and Marble Arch Caves.

The stalagmite and stalactite are the two main subsurface features in a Carboniferous Limestone area. These are formed when rainwater - a weak carbonic acid capable of dissolving limestone - percolates through it via the grykes and joints underground. This means the limestone is pervious. As this happens the limestone is dissolved and removed in solution. Caverns are often found below the surface in the limestone and as the lime-rich water finds its way underground it begins to drip from the roof of the cavern. It is cold underground so there is little evaporation but some does take place leaving a trace of limestone on the roof. Over thousands of years a stalactite forms from the ceiling as the water continues to drip. When the water drips on to the floor of the cavern some evaporation occurs here also leaving a trace of limestone. Again over thousands of years a stalagmite is formed. A stone pillar is formed when a stalagmite and stalactite meet.

Economics

Because it is brittle, the use of Carboniferous Limestone for building stone tends to be limited to those areas where it is the most abundantly available rock. However it is extensively quarried for other purposes:

- It is crushed for roadstone and aggregate wherever it outcrops, particularly in the Mendips and north Wales.

- It is burned for lime in many places. In certain places (e.g. Tunstead in the Peak District, and Horton in Ribblesdale in the Pennines), it is sufficiently pure for production of chemical-grade lime.

- It is used in cement manufacture at plants in England (4), Wales (2), Scotland (1) and Ireland (4).

- In ground form, it is used for power industry flue-gas desulphurisation.

- In many places it is metalliferous, and has yielded lead (in the Peak District and Weardale), and copper (in North Wales, where important Bronze Age mines are to be found).

- It was important in the early Industrial Revolution when, following the inventions of Abraham Darby, it was used in combination with nearby coal and ironstone from the Coal Measures in the iron industry.

See also

References

- ↑ Cossey P.J. & Adams A.E. (2004). "British Lower Carboniferous Stratigraphy". Geological Conservation Review series 29: 1–12.

- ↑ British Geological Survey 1:50,000 scale map series sheet E244/5 Pembroke & Linney Head

- ↑ British Geological Survey 1:50,000 scale map series sheet E229 Carmarthen, 230 Ammanford & 231 Merthyr Tydfil

- ↑ British Geological Survey 1:50,000 scale map series sheet E232 Abergavenny, 249 Newport

- ↑ British Geological Survey 1:50,000 scale map series sheets E246 Worms Head & 247 Swansea

- ↑ British Geological Survey 1:50,000 scale map series sheet E261/2 Bridgend

- ↑ British Geological Survey 1:50,000 scale special map sheet Isle of Man

- ↑ British Geological Survey 1:50,000 scale special map sheet Anglesey

- ↑ British Geological Survey 1:50,000 scale maps E94 Llandudno, E95 Rhyl, E96 Liverpool, E107 Denbigh, E108 Flint, E121 Wrexham, E137 Oswestry

- ↑ British Geological Survey 1:50,000 scale map E99 Chapel en le Frith, E111 Buxton, E124 Ashbourne

- ↑ British Geological Survey 1:50,000 scale map E40 Kirkby Stephen, E50 Hawes, E60 Settle

- ↑ British Geological Survey 1:50,000 scale map E48 Ulverston

- ↑ British Geological Survey 1:50,000 scale map E28 Whitehaven

- ↑ British Geological Survey 1:625,000 scale geological map Bedrock Geology UK North NERC 2007