Capture of Lesboeufs

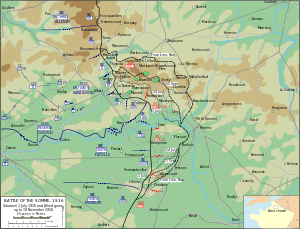

Lesbœufs (French pronunciation: [lebø]) is a village on the D 74 between Gueudecourt and Morval, about 30 miles (48 km) north-east of Amiens; Le Transloy lies to the north-west and Bapaume is to the north. French territorials fought the II Bavarian Corps on the north bank of the Somme in late September 1914, after which the front line moved west past Lesbœufs. Little military activity occurred round the village until the beginning of the Battle of the Somme, when German troops passed through the village in the first weeks of the battle. During the Battle of Flers–Courcelette (15–22 September), advances by the right flank corps of the British Fourth Army, brought the front line forward to the Gallwitz Riegel trenches west of Lesbœufs but exhaustion prevented the British from reaching their third objective, a line east of Morval, Lesbœufs and Gueudecourt.

A combined offensive was prepared by the Fourth Army and the French Sixth Army but was postponed several times because of inclement weather and the Battle of Morval took place from 25–26 September. In the British sector, the final objectives of the Battle of Flers–Courcelette were captured, the 52nd Reserve Division garrison in Gallwitz Riegel (Gird Trench and Gird Support Trench) and Lesbœufs being overwhelmed by brigades of the 6th Division and the Guards Division. No German troops were available to counter-attack and the village was consolidated. The capture of Gueudecourt next day, linked the new front line between the villages.

Lesbœufs was transferred to the control of the Sixth Army a few days later to enable the French to attack Sailly-Saillisel from the west. British attacks in the vicinity continued during the Battle of Le Transloy (1–28 October). During the rest of the winter of 1916–1917, offensive operations in the area diminished to shelling, sniper fire and trench raiding; the area became quiet after the German retreat to the Hindenburg Line in March 1917. The village was captured in March 1918 by the Germans during Operation Michael, the German spring offensive and reoccupied for the final time on 29 August, by the 38th Division, during the Second Battle of Bapaume.

Background

1914

On 25 September, during the Race to the Sea a French attack north of the Somme against the II Bavarian Corps (General Karl Ritter von Martini), forced a hurried withdrawal. As more Bavarian units arrived in the north, the 3rd Bavarian Division advanced along the north bank of the Somme, through Bouchavesnes, Leforest and Hardecourt until held up at Maricourt. The 4th Bavarian Division further to the north, defeated French Territorial divisions and then attacked westwards in the vicinity of Gueudecourt, towards Albert, through Sailly, Combles, Guillemont and Montauban, leaving a flank guard on the northern flank.[1] The II Bavarian Corps and XIV Reserve Corps (Generalleutnant Hermann von Stein) pushed back a French Territorial division from the area around Bapaume and advanced towards Bray-sur-Somme and Albert, as part of an offensive down the Somme valley to reach the sea.[2] The German offensive was confronted north of the Somme by the northern corps of the French Second Army east of Albert.[3] The XIV Reserve Corps attacked on 28 September, along the Roman road from Bapaume to Albert and Amiens, intending to reach the Ancre and then continue westwards along the Somme valley. The 28th (Baden) Reserve Division advanced close to Fricourt, against scattered resistance from French infantry and cavalry.[4]

1916

During the Battle of Albert (1–13 July), troops of Bavarian Infantry Regiment 16 of the 10th Bavarian Division, had lost many casualties in the fighting around Mametz and Trônes Wood, III Battalion having been reduced to 236 men by the time of the beginning of the Battle of Bazentin Ridge (14–17 July). The 7th Company, having been based in the south-east of Longueval, retreated at 8:00 a.m. through artillery and machine-gun fire to Gueudecourt. The survivors saw that the way through Ginchy and Lesbœufs was open to the British but by evening reinforcements had arrived and closed the gap either side of Foureaux (High) Wood.[5] On 27 August, Delville Wood had fallen and a counter-attack was planned for 31 August by three regiments of the 56th Division and the 4th Bavarian Division. Infantry Regiment 88 advanced through Le Transloy, Lesbœufs and Flers, where there were still fields with standing crops, towards the front line.[6]

On 14 September, field gunners behind the line saw British artillery bombardments falling on German defences along the Ginchy–Gueudecourt road and Gallwitz Riegel (the Gird Trenches). On 15 September, the British used tanks for the first time in the Battle of Flers–Courcelette and an extraordinary vehicle was engaged by Field Artillery Regiment 78, which hit the vehicle and then shot down the crew as they emerged. From the gun positions of Field Artillery Regiment 77, German infantry were seen to retire towards Lesbœufs, which left the road towards the artillery unprotected. British infantry were engaged but they reached Flers and by 11:30 a.m., outflanked the gunners who retired to Gueudecourt, as the British emerged from Ginchy, Delville Wood and Flers and advanced towards Lesbœufs but the efforts of the artillery with remaining field guns managed to prevent the British from overrunning Gallwitz Riegel.[7]

Small parties from the Guards Division, advanced on Lesbœufs and eventually took cover in a trench for several hours, before falling back during a German counter-attack. For several hours the village had been unoccupied but no British reserves were left, after the great number of casualties inflicted on the 56th, 6th and Guards divisions earlier in the day, many caused by a decision to leave tank lanes in the British barrage, which left several German machine-gun nests undamaged. Few lanes were used by the tanks, most of which broke down early or were knocked out. The Guards Division eventually dug in short of the final objective, west of the Gird Trenches in front of Lesbœufs.[8]

Prelude

British offensive preparations

The 6th Division (Major-General Charles Ross), was relieved from 16–20 September, then returned to the line on 21 September and began to dig assembly trenches. The most advanced position was in a captured trench The most forward portion of the line taken over by the Division consisted of part of the third objective attacked in the Battle of Flers–Courcelette, 250 yards (230 m) of a trench held by the Germans on both flanks. Several prisoners were taken when ration parties blundered into the occupied part of the trench, who gave useful information. A German attack on 24 September, against both flanks of the trench under cover of a mist, was driven back except on the extreme right, where a bombing post was entered but the Germans were then forced out, eleven being killed and a prisoner being taken.[9]

The Guards Division (Major-General G. P. T. Feilding) was withdrawn from the front line by 17 September for three days, to reorganise after the Battle of Flers–Courcelette. Replacement of the 4,964 casualties incurred from 10–17 September was easier than in other divisions as plenty of trained Guards reserves were available. At a conference on 19 September, the commander Major-General Feilding stressed the importance of maintaining direction during the attack despite the difficulties and that the 1st and 3rd Guards brigades should make special arrangements for attacking Germans troops in the cellars and dug-outs of Lesbœufs. Jumping-off trenches were to be dug in sheltered areas and battalions in reserve were to be ready behind the jumping-off points, to forestall a German counter-barrage and to engage a German counter-attack, if the attacking battalions were repulsed. By 21 September, the 1st Guards Brigade had relieved the 60th Brigade on the right and the 59th Brigade on the left was relieved by the 3rd Guards Brigade.[10]

British plan of attack

The 6th Division was to take the ground from the north side of Morval to a road through the centre of Lesbœufs, with the 16th Brigade on the right and the 18th Brigade on the left flank.[11] Because of the advanced position in Gird Trench (Gallwitz Riegel), no artillery bombardment was to be fired, instead a massed machine-gun and Stokes mortar bombardment was to begin at zero hour.[12][Note 1] Objectives for the Guards Division were set at the green line (first objective) a 1,500 yards (1,400 m) line north from 500 yards (460 m) west of Lesbœufs along a road from Ginchy to the village. The brown line (second objective) ran from a cross-roads south of the village along the western fringe and the blue line (final objective) ran from the Lesbœufs–Le Transloy road east of the village to the Lesbœufs–Gueudecourt road. A flow of troops was to be maintained to keep up the momentum of the advance up to the final objective and three tanks allotted to the division were to assemble at Trônes Wood, move up to Ginchy after the attack commenced and then advance to the divisional headquarters at Minden Post. The divisional artillery was split into two groups, one for each brigade and were to begin a bombardment of the German positions from 7:00 a.m.–6:00 p.m. During the attack, half of the guns were to place standing barrages and half to fire a creeping barrage. At zero hour a barrage was to stand on the green line and then jump to the second and third objectives as the creeping barrage, beginning 100 yards (91 m) in front of the jumping-off trenches was to move at 50 yards (46 m) per minute and then stop 200 yards (180 m) beyond the green line. One hour after zero hour the creeper was to move on, halting beyond the brown line and then moving after another hour to the brown line.[16]

German defensive preparations

Afer the sacking of Erich von Falkenhayn, the German Chief of the General Staff on 29 August, his successors General Paul von Hindenburg and General Erich von Ludendorff visited the Western Front and ordered an end to offensive operations at the Battle of Verdun and the reinforcement of the Somme front. Tactics were reviewed and a more "elastic" defence was advocated, to replace the defence of tactically unimportant ground and the routine counter-attacking of Allied advances. After the Battle of Flers–Courcelette, all of the divisions from Combles to Thiepval had to be relieved and the defences around Lesbœufs were taken over by the 52nd Reserve Division.[17] Gird Trench and Gird Support Trench (Gallwitz Riegel), 500 yards (460 m) apart, had been dug by the Germans against an attack from the south-west. The Gird trenches ran north-west to south-east, behind the Butte de Warlencourt. Seven Dials and Factory Corner protected the village against attacks from Eaucourt l'Abbay to the west. On the road north-west to Ligny–Thilloy, Luisenhof Farm had been fortified.[18]

Battle

25 September

The weather dawned fine and the ground was much drier than on 15–16 September.[19] The 6th Division attacked at 12:35 p.m., from the left of the 5th Division north of Morval, to the road through the middle of Lesbœufs. The first objective was taken by one battalion of the 16th Brigade on the right and two battalions of the 18th Brigade on the left. The final objective east of the Morval–Lesbœufs road was captured by two battalions leap-frogging through on the right and one on the left, to clear the south end of Lesbœufs, where the Guard Division was met as it occupied the north end. Two battalions of Reserve Infantry Regiment 239 were overrun and 500 prisoners were taken.[20] The 6th Division consolidated on spurs east and north-east of Morval, in touch with the 5th Division on the right. At 6:00 p.m. the adjoining brigades advanced another 200 yards (180 m) east of Morval and also put posts on a line from Morval Mill north to Lesbœufs.[21]

The Guards Division attacked with two brigades in line, each brigade having two battalions forward and two in support. The infantry of the 1st Guards Brigade advanced in waves 75 yards (69 m) apart, on a line from the Ginchy–Lesbœufs road to a point 500 yards (460 m) to the north-west. On the left, the 3rd Guards Brigade attacked on another 500 yards (460 m) front to the 20th Division boundary, against the infantry of Reserve Infantry Regiment 240 of the 52nd Reserve Division.[22] A German counter-barrage began on the 1st Guards Brigade front line as soon as the infantry advance began, causing many casualties to the support battalions. The foremost waves moved fast enough to avoid the bombardment and were close to the German front line, when the standing barrage lifted. Uncut wire and fire from dug-outs along a sunken road delayed the right-hand battalion; the wire was cut by the officers, who were sniped at by the defenders and had many casualties. The men provided covering fire, then rushed the first objective at about 12:40 p.m. The green line was captured by both battalions by 1:20 p.m. The advance to the next objective at 1:35 p.m. took ten minutes, against "slight" opposition and contact was made with the 18th Brigade of the 6th Division and the 3rd Guards Brigade on the left. At 2:35 p.m. the advance to the final objective began was conducted against little resistance, many Germans surrendering. The 1st Guards Brigade battalions began to dig in on the east side of Lesbœufs by 3:30 p.m.[23]

The 3rd Guards Brigade advanced on time behind the creeping barrage and the right-hand battalion reached the green line easily with few casualties. on the left an undamaged German trench was found to be full of infantry who made a determined defence and caused many casualties; about 150 Germans were killed. The battalion reorganised and reached the first objective at 1:35 p.m. and then found that the left flank was open, due to the 64th Brigade on the right of the 21st Division had been delayed short of Gird Trench by uncut wire. A defensive flank was formed and the remaining troops advanced to the second objective. Two companies were sent forward from a supporting battalion to reinforce the flank and the second objective (green line) was reached by the remaining troops of the leading battalions. The second supporting battalion passed through the foremost troops at the second line and reached the brown line at 3:30 p.m. Touch was gained with the 6th Division north of Lesbœufs; a further advance in the evening was postponed due to the vulnerable northern flank, although the disarray seen among the German defenders further south led local commanders to call for cavalry, to exploit the "rout" they believed was occurring south of Gueudecourt, where British artillery inflicted many casualties on retreating parties of Germans.[24]

Aftermath

Analysis

The attack by XIV Corps had captured the last prepared German defences on a 2,000 yards (1,800 m) front, forced a swift retirement on the German field artillery and took many prisoners, some so demoralised that 100 men gave up to one soldier. A German bombardment began on Lesbœufs as soon as it was occupied but the area was mostly avoided during the consolidation and few casualties were caused. All of the objectives on the Guards Division front had been taken and the two brigades dug in from the Lesbœufs–Le Transloy road to Windy Trench. Touch was gained with the 6th Division but a gap on the left next to the 21st Division was covered by a defensive flank. The uncertainty about the left flank led Fielding and the corps commander to decide not to attempt to exploit the victory at Lesbœufs, despite the disarray observed among the German survivors, who were seen retreating without weapons.[22]

The failure to take Gueudecourt to the north constricted the front from which an exploitation could be mounted and night was soon to fall. T. O. Marden the 6th Division historian and commander of the 114th Brigade, 38th Division in 1916, called the attack one of the most successful on the Somme and that good weather, good observation, a carefully arranged creeping barrage and an effective preliminary bombardment contributed to the victory.[11] Parts of the 51st and 52nd Reserve divisions counter-attacked to recapture Morval further south but were only able to advance a short distance and cover the withdrawal of their artillery, eventually forming new a line along the Le Transloy road, 1,000 yards (910 m) east of Morval but no troops were available to counter-attack at Lesbœufs. The village and Morval were later handed over to the French Sixth Army, to assist with the attack on Sailly-Saillisel.[25]

Casualties

The 6th Division took 500 prisoners, six machine-guns and four heavy trench mortars.[11] The division lost 5,000 casualtiesfrom 14–30 September.[26] The Guards Division had 2,340 casualties from 18–30 September, about 90% being suffered on 25 September.[27]

Subsequent operations

After the Battle of Morval, the Fourth Army began attacks northwards, against the German defences beyond Flers, up the Flers and Gird lines but communication trenches between them, were used as improvised defences by the Germans. Attacks by XIV and XV corps beyond Lesbœufs and Gueudecourt were only able to advance a few hundred yards/metres. The German defence of the fourth main defensive line along Transloy Ridge during the Battle of Le Transloy in October succeeded, despite a mixture of general and local attacks. By attacking in the area from Lesbœufs to Le Sars, the British pushed into lower boggy ground overlooked by the Germans on the Transloy Ridge.[28] On 2 November, Rupprecht wrote in his diary that the British were digging in west of Delville Wood to Martinpuich and Courcelette, which suggested that winter quarters were being built and that only minor operations were contemplated. Infantry attacks diminished but British artillery fire was constant, against which the large number of German guns in the area could only make a limited reply, due to a chronic shortage of ammunition. German counter-attacks were cancelled because of troop shortages.[29] During the winter lull of 1916–1917, sniping, trench raiding and artillery exchanges continued until the German retreat to the Hindenburg Line in March 1917.[30]

1918

Lesbœufs was lost on 24 March 1918, during the retreat of the 47th Division and the 63rd Division during Operation Michael, the German spring offensive.[31][Note 2] The village was recaptured for the last time on 29 August, by the 10th South Wales Borderers of the 38th Division, during the Second Battle of Bapaume.[34][35]

Notes

- ↑ The British plan was for an advance of 1,200–1,500 yards (1,100–1,400 m) to reach the final objective which had been set for the attacks of 15–22 September, during the Battle of Flers–Courcelette. The ground to be taken was on the east side of Bazentin ridge, which ran north-west from the Somme to a hollow facing north-east with Combles at the west end, the hollow running towards Rocquigny beyond the Péronne–Bapaume road. North of the hollow lay Morval, Lesbœufs and Gueudecourt, then the Albert–Bapaume road, west of Le Sars to Thiepval. Spurs ran down the eastern slope, generally to the north-east in the direction of the Péronne–Bapaume road, before the ground rose again from St Pierre Vaast Wood to Sailly-Saillisel, Le Transloy, Beaulencourt and Thilloy.[13] An advance on the main front of the British attack of 1,200–1,500 yards (1,100–1,400 m), was to be made in three stages. The first stage was an advance to the third of the objective lines set for 15 September and to the Gird Trenches (Gallwitz Riegel) south of Gueudecourt, beginning at 12:35 p.m., the second objective was a line along the sunken road running from Combles to Gueudecourt west of Morval and Lesbœufs, then over a spur south-east of Gueudecourt and through the centre of the village, beginning at 1:35 p.m. The final objective was on the east side of Morval, Lesbœufs and Gueudecourt, the advance beginning at 2:35 p.m. with the objectives to be reached by 3:00 p.m.[14] Tanks were to be kept in reserve, due to the difficulty of hiding them for a daylight attack, ready to assist the attack on the villages at the final objective. Two brigades of the 1st Indian Cavalry Division were to move forward to Mametz, with all the division to be ready to advance on Ligny-Thilloy in the III Corps area, once Lesbœufs and Gueudecourt were captured, if this had been achieved before 6:30 p.m. Small cavalry detachments were also attached to XIV Corps and XV Corps to exploit local opportunities.[15]

- ↑ 63rd Division machine-gunners were deployed south of the village but the divisional history treats Lesbœufs as a 47th Division responsibility.[32] The 47th Division set up its headquarters in the village on 24 March during the retreat from the Flésquières and retired through Gueudecourt. The divisional history blamed the 63rd Division for retreating abruptly.[33]

Footnotes

- ↑ Sheldon 2005, pp. 19, 22, 26, 28.

- ↑ Edmonds 1926, pp. 401–402.

- ↑ Edmonds 1926, pp. 402–403.

- ↑ Sheldon 2005, pp. 26, 28.

- ↑ Sheldon 2005, pp. 196–198.

- ↑ Sheldon 2005, pp. 257–258.

- ↑ Sheldon 2005, pp. 294–296.

- ↑ Philpott 2009, p. 365.

- ↑ Marden 1920, p. 24.

- ↑ Headlam 1924, pp. 165–166.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Marden 1920, p. 25.

- ↑ Miles 1938, p. 371.

- ↑ Jones 1928, pp. 202–203.

- ↑ Miles 1938, p. 370.

- ↑ Miles 1938, pp. 371–372.

- ↑ Headlam 1924, pp. 168–169.

- ↑ Miles 1938, pp. 423–425.

- ↑ Gliddon 1987, pp. 199–200.

- ↑ Headlam 1924, p. 170.

- ↑ Marden 1920, pp. 24–25.

- ↑ McCarthy 1993, p. 116.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Miles 1938, p. 376.

- ↑ Headlam 1924, pp. 170–171.

- ↑ Headlam 1924, pp. 172–173.

- ↑ Miles 1938, pp. 375–377.

- ↑ Miles 1938, p. 429.

- ↑ Headlam 1924, p. 176.

- ↑ Philpott 2009, pp. 394–395, 408.

- ↑ Sheldon 2005, p. 371.

- ↑ Falls 1940, pp. 127–135.

- ↑ Edmonds, Davies & Maxwell-Hyslop 1935, p. 425.

- ↑ Jerrold 1923, p. 283.

- ↑ Maude 1922, pp. 159–161.

- ↑ Edmonds 1947, p. 344.

- ↑ Munby 1920, p. 56.

References

- Edmonds, J. E. (1926). Military Operations France and Belgium 1914: Mons, the Retreat to the Seine, the Marne and the Aisne August–October 1914. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence I (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan. OCLC 58962523.

- Edmonds, J. E.; Davies, H. R.; Maxwell-Hyslop, R. G. B. (1935). Military Operations France and Belgium 1918: The German March Offensive and its Preliminaries. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence I (IWM and Battery Press 1995 ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-89839-219-5.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1947). Military Operations France and Belgium 1918: 8th August – 26th September The Franco-British Offensive. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence IV (IWM and Battery Press 1993 ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 0-89839-191-1.

- Falls, C. (1940). Military Operations France and Belgium, 1917: The German Retreat to the Hindenburg Line and the Battles of Arras. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence I (IWM & Battery Press 1992 ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 0-89839-180-6.

- Gliddon, G. (1987). When the Barrage Lifts: A Topographical History and Commentary on the Battle of the Somme 1916. Norwich: Gliddon Books. ISBN 0-947893-02-4.

- Headlam, C. (1924). History of the Guards Division in the Great War 1915–1918 I (Naval & Military Press 2010 ed.). London: John Murray. ISBN 1-84342-124-0. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- Jerrold, D. (1923). The Royal Naval Division (N & M Press 2009 ed.). London: Hutchinson. ISBN 1-84342-261-1.

- Jones, H. A. (1928). The War in the Air, Being the Story of the Part Played in the Great War by the Royal Air Force (PDF) II (N & M Press 2002 ed.). London: Clarendon Press. ISBN 1-84342-413-4. Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- Marden, T. O. (1920). A Short History of the 6th Division August 1914 – March 1919 (BiblioBazaar 2008 ed.). London: Hugh Rees Ltd. ISBN 1-43753-311-6. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- Maude, A. H. (ed.) (1922). The 47th (London) Division, 1914–1919 by Some who Served with it in the Great War. London: Amalgamated Press. OCLC 494890858. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- McCarthy, C. (1993). The Somme: The Day-by-Day Account (Arms & Armour Press 1995 ed.). London: Weidenfeld Military. ISBN 1-85409-330-4.

- Miles, W. (1938). Military Operations France and Belgium, 1916, 2nd July 1916 to the End of the Battles of the Somme. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence II (IWM & Battery Press 1992 ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-901627-76-3.

- Munby, J. E. (ed.) (1920). A History of the 38th (Welsh) Division: by the GSO's.I of the Division (M & M Press 2003 ed.). London: Hugh Rees. ISBN 1-84342-583-1. OCLC 495191912. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- Philpott, W. (2009). Bloody Victory: The Sacrifice on the Somme and the making of the Twentieth Century (1st ed.). London: Little, Brown. ISBN 978-1-4087-0108-9.

- Sheldon, J. (2005). The German Army on the Somme 1914–1916 (Pen & Sword Military 2006 ed.). London: Leo Cooper. ISBN 1-84415-269-3.

Further reading

- Browne, D. G. (1920). The Tank in Action (PDF). Edinburgh: W. Blackwood. OCLC 699081445. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- Duffy, C. (2006). Through German eyes: The British and the Somme 1916 (Phoenix 2007 ed.). London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson. ISBN 978-0-7538-2202-9.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1925). Military Operations France and Belgium, 1914: Antwerp, La Bassée, Armentières, Messines and Ypres October–November 1914 (PDF). History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence II (1st ed.). London: Macmillan. OCLC 220044986. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1932). Military Operations France and Belgium, 1916: Sir Douglas Haig's Command to the 1st July: Battle of the Somme. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence I (IWM & Battery Press 1993 ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-89839-185-7.

- Fuller, J. F. C. (1920). Tanks in the Great War, 1914–1918 (PDF). New York: E. P. Dutton. OCLC 559096645. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- Haigh, R. (1918). Life in a Tank (PDF). New York: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 1906675. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- Prior, R.; Wilson, T. (2005). The Somme. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10694-7.

- Rogers, D. (ed.) (2010). Landrecies to Cambrai: Case Studies of German Offensive and Defensive Operations on the Western Front 1914–17. Solihull: Helion. ISBN 978-1-906033-76-7.

- Watson, W. H. L. (1920). A Company of Tanks (PDF). Edinburgh: W. Blackwood. OCLC 262463695. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- Williams-Ellis, A.; Williams-Ellis, C. (1919). The Tank Corps (PDF). New York: G. H. Doran. OCLC 317257337. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Capture of Lesbœufs. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||