Capture of La Boisselle

La Boisselle was a village on the D 929 road, 22 miles (35 km) north-east of Amiens, at the junction of the D 104 to Contalmaison. To the north-west across the road, lay Ovillers. (By 1916, that village was called Ovillers by the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) to avoid confusion with Ovillers La Boisselle south of the road, which was called La Boisselle.) In 1914, the village had 35 houses. Military operations began in the area after the beginning of the Great Retreat, which followed the defeat of the Franco-British armies in Belgium in August 1914. In September, French and German armies moving north from the Aisne, made reciprocal attempts to outflank their opponent to the north, which led to the Race to the Sea, during which the Battle of Albert (1914) was fought from 25–29 September.

Trench warfare and mining began on the Somme front in late 1914, particularly at the west end of La Boisselle, where no man's land was unusually narrow. From 17–21 December a French offensive managed to capture a small amount of ground to the south-west of the village and both sides returned to mining and counter-mining, which continued through 1915. From April 1915 – January 1916, sixty-one mines were sprung around the Granathof at the south-west fringe of La Boisselle, some with 20,000–25,000-kilogram (44,000–55,000 lb) explosive charges. In mid-July 1915, extensive troop and artillery movements north of the Ancre were seen by German observers and on 9 August, the arrival of the British was confirmed when a British soldier was captured.

On 1 July 1916, La Boisselle was attacked by the 34th Division of III Corps but the bombardment had not damaged the German deep-mined dug-outs (minierte stollen) and a German listening post overheard a British telephone conversation, which gave away the attack to be made the next day. The III Corps divisions lost more than 11,000 casualties and failed to capture La Boisselle or Ovillers, gaining only small footholds near the boundary with XV Corps to the south and at Schwabenhöhe, after the Lochnagar mine explosion had destroyed some of the defences of Reserve Infantry Regiment 110. The advance of the 103rd Brigade was over ground with a fold, which meant that the disastrous attack by the preceding brigades could not be seen as the brigade advanced to be engaged by artillery and machine-gun fire, which inflicted 70% casualties, before the troops had reached the British front line.

The 19th (Western) Division was rushed forward from reserve, in case of a German counter-attack on Albert. The 19th Division continued the attack and captured most of the village by 4 July. After the Battle of Albert (1916) (1–13 July), La Boisselle became a backwater. The village was re-captured by the Germans on 25 March 1918, during the retreat of the 47th (1/2nd London) Division and the 12th (Eastern) Division in Operation Michael, the German spring offensive. In the afternoon, air reconnaissance saw that the British defence of the line from Montauban and Ervillers was collapsing and the RFC squadrons in the area made a maximum effort to disrupt the German advance. The village and vicinity were captured by the Allies for the last time on 26 August, by the 38th (Welsh) Division during the Second Battle of Bapaume (31 August – 3 September).

Background

1914

In 1914, La Boisselle was a village of 35 houses on the right of the D 929 Albert–Bapaume road, at the junction of the D 104 to Contalmaison. To the north-west across the road, lay Ovillers la Boisselle. (By 1916, the village was called Ovillers by the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) to avoid confusion with Ovillers La Boisselle south of the road, which became La Boisselle.)[1] On 26 September, the French 11th Division attacked eastwards, north of the Somme but after French Territorial divisions were forced back from Bapaume, the division was ordered back, to defend bridgeheads from Maricourt to Mametz.[2] The II Bavarian Corps attacked on 27 September, between the Somme and the Roman road from Bapaume to Albert and Amiens, intending to reach the Ancre and then continue westwards along the Somme valley. The 3rd Bavarian Division advanced close to Montauban and Maricourt, against scattered resistance from French infantry and cavalry. On 28 September, the French were able to stop the German advance on a line from Maricourt to Fricourt and Thiepval.[3]

The XIV Reserve Corps began operations west of Bapaume on the same day, by advancing down the Bapaume–Albert road to the Ancre river before advancing down the Somme valley to Amiens but by 29 September, the advance was stopped by the French around Fricourt and La Boisselle.[3] A night attack on Bécourt was planned for the evening of 7 October, to capture Albert but the infantry found that keeping direction in the dark was impossible. Small-arms fire from well dug-in French troops added to the confusion and the attack collapsed, 400 German troops being captured in the fiasco.[4] In early November French artillery reinforcements arrived and bombardments beyond the front line began. On 19 November, two divisions of XI Corps attacked to fix German troops but were repulsed and on 28 November, an attack by the XIV Corps managed to advance the French line by 300–400 metres (330–440 yd). In early December, IV Corps attacked and gained 300–1,000 metres (330–1,090 yd). The French attacks had been costly and pushed forward the front line only a small amount.[5]

Attacks by the French 53rd Reserve Division of XI Corps, took place from 17 December, at La Boisselle, Mametz, Carnoy and Maricourt.[6] Although wire-cutting had not been completed, the operation was ordered to begin at 6:00 a.m., without artillery support, to gain a measure of surprise. The attack got beyond the German front line near Mametz and north of Maricourt and then repulsed German counter-attacks from Bernafay Wood and east of Mametz. The advance had been contained by German reserves in the support lines and by flanking machine-gun fire. The 118th Battalion reached the cemetery of La Boisselle and the 19th Infantry Regiment closed on the western fringe of Ovillers. A German counter-bombardment then swept the ground west of Ovillers and ravine 92, which prevented the approach of French reserves. During the night the French survivors of the attack fell back to the French front line, except at La Boisselle.[7]

Next day the XI Corps broke through the German defences at La Boisselle cemetery but was stopped a short distance forward, in front of trenches protected by barbed wire. A German counter-attack using incendiary grenades recaptured a trench north of Maricourt and a French counter-attack at 10:30 a.m., by two battalions of the 45th Infantry Regiment and a battalion of the 236th Infantry Regiment, managed to regain a small amount of ground.[7] A German counter-attack on 21 December, near Carnoy was repulsed.[6] On 24 December, XI Corps attacked again at La Boisselle, the 118th Infantry Regiment and two battalions of the 64th Infantry Regiment attacked at 9:00 a.m. after a bombardment. The 118th Regiment captured a small number of houses in the south-east of La Boisselle and consolidated the area during the night. The 64th Regiment overran the German first line but was held up short of a second trench, which had not been discovered before the attack and then dug in, having lost many casualties.[7]

On 27 December, a German bombardment on the captured positions in La Boisselle was followed by a counter-attack on the 118th and 64th regiments, which was repulsed. German heavy artillery reinforcements had been brought into the area and made the area untenable; the French infantry were withdrawn and mine warfare began.[7] Many of the German units on the Somme in 1914 remained and had made great efforts to fortify the defensive line, particularly with barbed-wire entanglements so that the front trench could be held with fewer troops. Railways, roads and waterways connected the battlefront to the Ruhr from where material for minierte Stollen (dug-outs) 20–30 feet (6.1–9.1 m) underground for 25 men each could excavated every 50 yards (46 m) and the front divided into Sperrfeuerstreifen (barrage sectors).[8]

1915

January began frosty, which solidified the ground but wet weather followed and soon caused trenches and all other diggings to collapse, which made movement impossible after a few days, leading to tacit truces to allow supplies to be carried to the front line at night.[9] The rains eased and Bavarian Engineer Regiment 1 continued digging eight galleries at the south end of the village, towards Granathof (Shell Farm) which had been captured by the French in December. On 5 January, French sappers were heard digging near a gallery and a 300-kilogram (660 lb) camouflet was quickly placed in the gallery and blown, collapsing the French digging and two German galleries in the vicinity. A 600-kilogram (1,300 lb) charge was blown on 12 January, which killed more than forty French soldiers. On 18 January, Reserve Infantry Regiment 120 made a surprise attack and destroyed the 7th and 8th companies of the 65th Infantry Regiment, taking 107 prisoners. Fighting took place at La Boisselle for the rest of the year and on the night of 6/7 February, three more German mines were sprung close to the Granathof.[10]

After the explosions, a large party of German troops advanced and occupied the demolished houses but were not able to advance further against French artillery and small-arms fire. At 3:00 p.m. a French counter-attack drove back the Germans and inflicted about 150 casualties. For several more days both sides detonated mines and conducted artillery bombardments, which often prevented infantry attacks. On 1 March, at Bécourt, German infantry massing for an attack were stopped by French artillery and at Carnoy on 15 March, a German mine was sprung and crater-fighting ensued for several days.[11] On the night of 8/9 March, a German sapper inadvertently broke into French gallery, which was found to have been charged with explosives; a group of volunteers took 45 nerve racking minutes to dismantle the charge and cut the firing cables. From April 1915 – January 1916, sixty-one mines were sprung around the Granathof, some with 20,000–25,000 kilograms (44,000–55,000 lb) of explosives.[12]

Erich von Falkenhayn, the German Chief of the General Staff ordered a construction plan in January 1915, to create a systematic defensive system on the Western Front, capable of withstanding attacks indefinitely with a relatively small garrison. Barbed wire obstacles were enlarged from one belt 5–10 yards (4.6–9.1 m) wide to two, 30 yards (27 m) wide and about 15 yards (14 m) apart. Double and triple thickness wire was used and laid 3–5 feet (0.91–1.52 m) high. The front line was increased from one trench to three, dug 150–200 yards (140–180 m) apart, the first trench (Kampfgraben) to be occupied by sentry groups, the second (Wohngraben) for the front-trench garrison and the third trench for local reserves. The trenches were traversed and had sentry-posts in concrete recesses built into the parapet. Dugouts had been deepened from 6–9 feet (1.8–2.7 m) to 20–30 feet (6.1–9.1 m), 50 yards (46 m) apart and made large enough for 25 men. An intermediate line of strong points (Stutzpunktlinie) about 1,000 yards (910 m) behind the front line was also built. Communication trenches ran back to the reserve line, renamed the second line, which was as well-built and wired as the first line. The second line was beyond the range of Allied field artillery, to force an attacker to stop and move artillery forward before assaulting the line.[13]

In mid-July 1915, extensive troop and artillery movements north of the Ancre were seen by German observers. The type of shell fired by the new artillery changed from high explosive to shrapnel and unexploded shells were found to be of a different design. The new infantry opposite did not continue the live-and-let-live practice between operations, of their forerunners and a larger number of machine-guns began firing against the German lines, which did not pause every 25 shots, like French Hotchkiss machine-guns. German troops were reluctant to believe that the British had assembled an army large enough to extend as far south as the Somme. A soldier seen near Thiepval was thought to be a French soldier in a grey hat but by 4 August, it was officially reported by Oberste Heeresleitung (OHL: General Headquarters) that the 52nd Division and the 26th Reserve Division had seen a man in a brown suit. On 9 August, the arrival of the British became certain, when Private William Nicholson of the 6th Black Watch, 51st (Highland) Division was shot and captured during a German trench raid. A second British soldier was captured when 1st East Lancashire troops of the 4th Division were wiring in no man's land. The soldier got lost in fog near the Ancre and blundered into the German lines near the biber kolonie.[14]

1916

After the Herbstschlacht ("Autumn Battle") in 1915, a third defence line another 3,000 yards (2,700 m) back from the Stutzpunktlinie was begun in February and was nearly complete on the Somme front when the battle began. German artillery was organised in a series of sperrfeuerstreifen (barrage sectors); each officer was expected to know the batteries covering his section of the front line and the batteries to be ready to engage fleeting targets. A telephone system was built, with lines buried 6 feet (1.8 m) deep for 5 miles (8.0 km) behind the front line, to connect the front line to the artillery. The Somme defences had two inherent weaknesses which the rebuilding had not remedied. The front trenches were on a forward slope, lined by white chalk from the subsoil and easily seen by ground observers. The defences were crowded towards the front trench, with a regiment having two battalions near the front-trench system and the reserve battalion divided between the Stutzpunktlinie and the second line, all within 2,000 yards (1,800 m) and most troops within 1,000 yards (910 m) of the front line, accommodated in the new deep dugouts. The concentration of troops at the front line on a forward slope, guaranteed that it would face the bulk of an artillery bombardment, directed by ground observers on clearly marked lines.[15] Digging and wiring of a new third line began in May, civilians were moved away and stocks of ammunition and hand-grenades were increased in the front-line.[16]

By mid-June, Below and Rupprecht expected an attack on the 2nd Army which held the front from Noyon to beyond Gommecourt, although Falkenhayn was more concerned about an offensive in Alsace-Lorraine and then a possible attack on the 6th Army, which held the front from near Gommecourt north to St. Eloi near Ypres. In April, Falkenhayn had suggested a spoiling attack by the 6th Army but lack of troops and artillery, which were engaged in the offensive at Verdun made it impractical. Some labour battalions and captured Russian heavy artillery were sent to the 2nd Army and Below proposed a preventive attack in May and a reduced operation from Ovillers to St. Pierre Divion in June but got only one extra artillery regiment. On 6 June, Below reported that an offensive at Fricourt and Gommecourt was indicated by air reconnaissance and that the south bank had been reinforced by the French, against whom the XVII Corps was overstretched, with twelve regiments to hold 36 kilometres (22 mi) and no reserves.[17]

In mid-June, Falkenhayn was sceptical of an offensive on the Somme, since a great success would lead to operations in Belgium, when an offensive in Alsace-Lorraine would take the war and its devastation into Germany. More railway activity, fresh digging and camp extensions around Albert opposite the 2nd Army, was seen by German air observers on 9 and 11 June and spies reported an imminent offensive. On 24 June, a British prisoner spoke of a five-day bombardment to begin on 26 June and local units expected an attack within days. On 27 June, 14 British observation balloons were visible, one for each British division but no German reinforcements were sent to the area until 1 July and only then to the 6th Army. At Verdun on 24 June, Crown Prince Wilhelm was ordered to conserve troops, ammunition and equipment and further restrictions were imposed on 1 July, when two divisions were put under OHL control.[18]

Prelude

British offensive preparations

| Date | Rain mm |

Temp (°F) |

Outlook |

|---|---|---|---|

| 23 | 2.0 | 79°–55° | windy |

| 24 | 1.0 | 72°–52° | overcast |

| 25 | 1.0 | 71°–54° | windy |

| 26 | 6.0 | 72°–52° | cloudy |

| 27 | 8.0 | 68°–54° | cloudy |

| 28 | 2.0 | 68°–50° | overcast |

| 29 | 0.1 | 66°–52° | cloudy windy |

| 30 | 0.0 | 72°–48° | overcast high winds |

| 1 | 0.0 | 75°–54° | clear hazy |

| 2 | 0.0 | 75°–54° | clear fine |

| 3 | 2.0 | 68°–55° | fine |

| 4 | 17.0 | 70°–55° | thunder storms |

| 5 | 0.0 | 72–52° | low cloud |

| 6 | 2.0 | 70°–54° | showers |

| 7 | 13.0 | 70°–59° | showers |

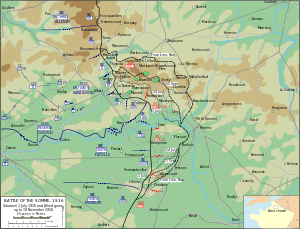

The British front line from Bécourt to Authuille, was held by III Corps and lay along the forward slope of a low ridge between La Boiselle and Albert, east of Tara and Usna hills, which was a continuation of the south-west spur from the main Bazentin Ridge on which Ovillers had been built. In dead ground behind the ridge field artillery was deployed in rows and artillery observers watched from positions on the ridge, with a perfect view of the German front position, which ran along the higher slopes of three spurs, which descend south-west from the main ridge, where each trench had an unmistakable white chalk parapet. No man's land varied from 50–800 yards (46–732 m) wide, the narrowest part opposite La Boisselle (Granathof) being known to the British as the Glory Hole. The right flank of the corps was opposite Fricourt Spur, the centre faced La Boisselle Spur, with the village just behind the front line and the left flank was west of Ovillers Spur. Depressions between the spurs were known as Sausage and Mash valleys, which were about 1,000 yards (910 m) wide at their broadest points, which made an advance up them vulnerable to cross-fire. The spurs were covered by trench networks and machine-gun posts and Thiepval Spur to the north opposite X Corps overlooked the ground across which the III Corps divisions must advance.[20]

The III Corps artillery had 98 heavy guns and howitzers and a groupe of the French 18th Field Artillery Regiment to fire gas shells. The corps artillery was divided into two field artillery groups for each attacking division and a fifth group which contained the heaviest artillery, to cover all the corps front. There was one heavy gun for each 40 yards (37 m) of front and a field gun for every 23 yards (21 m). The heavy group had 1 × 15-inch howitzer, 3 × 12-inch howitzers on railway mountings, 12 × 9.2-inch howitzers, 16 × 8-inch howitzers and 20 × 6-inch howitzers, 1 × 12-inch gun, 1 × 9.2-inch gun (both on railway mountings), 4 × 6-inch guns, 32 × 60-pounder guns and 8 × 4.7-inch guns. During the preliminary bombardment the III Corps artillery was hampered by poor-quality field gun ammunition, which caused premature shell-explosions in gun barrels and casualties to the gunners. Many howitzer shells fell short and there was a large number of blinds (duds). The unsatisfactory bombardment and the discovery on 30 June, that parties which left the British front line to clear paths through the British wire, had been fired on by the garrison of La Boisselle, led to a battery of eight Stokes mortars being readied to bombard La Boisselle at zero hour, until the flanking parties entered the village. Sausage Redoubt (Heligoland) was to be bombarded by Stokes mortars from an emplacement dug in no man's land overnight, 500 yards (460 m) opposite the strong point. (Long-range fire was more successful and a 12-inch railway gun chased Generalleutnant Hermann von Stein, the XIV Reserve Corps commander and his staff out of Bapaume on 1 July.)[21]

Lochnagar and Y Sap mines

French mine workings were taken over as the British moved into the Somme front and great secrecy was maintained to prevent the discovery of the mines, since no continuous front line trench ran through the Glory Hole, which was defended by posts near the mine shafts.[22] The mining was done by the 179th Tunnelling Company Royal Engineers, on either side of the salient around La Boisselle, intended to destroy German positions and create crater lips to block German enfilade fire along no man's land. The tunnellers used bayonets with spliced handles and worked barefoot on a floor covered with sandbags for silence. Flints were carefully prised out of the chalk and laid on the floor; when the bayonet was manipulated two-handed, an assistant caught the dislodged material. Spoil was placed in sandbags and passed hand-by-hand, along a row of miners sitting on the floor and stored along the side of the tunnel, later to be used to tamp the charge. The Lochnagar tunnel was 4.5 by 2.5 feet (1.37 m × 0.76 m) and excavated at a rate of about 18 inches (46 cm) per day, until about 1,030 feet (310 m) long, with galleries beneath the Schwabenhöhe. The mines were laid without interference by German miners but as the explosives were placed, Sappers could be heard below Lochnagar and above Y Sap. Lochnagar was loaded with 60,000 pounds (27,000 kg) of Ammonal, in two charges of 36,000 pounds (16,000 kg) and 24,000 pounds (11,000 kg), 60 apart and 52 feet (16 m) deep. Just north of the village, Y Sap was charged with 40,600 pounds (18,400 kg) of Ammonal.[23] Two smaller mines of 8,000 pounds (3,600 kg) each, were planted from galleries dug from Inch Street Trench.[24]

British plan of attack

In the III Corps area, heavy artillery was to fire on the German defences in eight lifts and "jump" from one defence line to the next and the infantry advance was to be preceded by barrages which moved back slowly on a timetable. The sixth lift was to fall on a line behind Contalmaison and Pozières, 85 minutes after zero hour and the eighth lift was to fall 1,000 yards (910 m) beyond after 22 minutes, a procession into the German defences of 2 miles (3.2 km) in 107 minutes. The field artillery barrage was to move "very slowly", raking back to the next German trench line in lifts of 50–100–150 yards (46–91–137 m) but was to move faster than the speed of the infantry advance, so was not a true creeping barrage.[25] On 28 June, the Fourth Army headquarters ordered that if the initial attacks caused the German defence to collapse, the closest infantry would exploit without waiting for cavalry of the Reserve Army commanded by Lieutenant-General Hubert Gough, which was assembled 5 miles (8.0 km) west of Albert and was to advance once the roads had been cleared.[26]

Gough had the 1st Cavalry Division, 2nd Indian Cavalry Division and 3rd Cavalry Division and the 12th (Eastern) Division (12th Division) and 25th Division, ready to advance through any gap formed and turn north, to roll up the German defences.[27] On the right flank of III Corps, the 34th Division, composed of Pals battalions, was to capture the German positions on the Fricourt Spur and Sausage valley to the far side of La Boisselle and then advance to a line about 800 yards (730 m) short of the German second line, from Contalmaison to Pozières. The division would have to capture a fortified village and six German trench lines, in a 2-mile (3.2 km) advance on a 2,000 yards (1,800 m) front. The 19th (Western) Division (19th Division) in corps reserve was to move forward to vacated trenches in the Tara–Usna line, ready to relieve the attacking divisions after the objectives had been reached.[21] If the German defences collapsed the 19th Division and 49th (West Riding) Division in reserve, were to advance either side of the Albert–Bapaume road under the command of the Reserve Army.[28]

All three infantry brigades of the division were to attack at zero hour in waves. Four columns three battalions deep were to attack on 400 yards (370 m) frontages, with a gap between the third and fourth columns either side of La Boisselle, which like Fricourt was not to be attacked directly. As the columns passed by, bombing parties supported by Lewis gun and Stokes mortar crews were to attack from both flanks. When the battalion and brigade commanders ventured to doubt the realism of the plan, they were reminded that the preliminary bombardment had killed the village garrison and the Lochnagar and Y Sap mines would have destroyed the fortifications, either side of the village salient. Two columns on the right flank were to be formed by the 101st Brigade (Brigadier-General R. C. Gore) with one battalion leading and a supporting battalion behind, followed by a battalion detached from the 103rd (Tyneside Irish) Brigade (Brigadier-General N. J. G. Cameron). The two columns on the left flank were from the 102nd (Tyneside Scottish) Brigade (Brigadier-General T. P. B. Tiernan) and the remaining two battalions of the 103rd Brigade were to follow the columns.[29]

Many of the divisional infantry had been coal miners before 1914 and dug an elaborate complex of underground galleries in Tara hill to shelter the assembled battalions. When the attack began, the columns were to advance in lines of companies in extended order, the companies moving in platoon columns 150 paces apart. Gore ordered the 101st Brigade the battalion headquarters staffs to stay behind until ordered forward, to preserve a cadre of officers to replace casualties. The first objective of the two leading lines of battalions was the German front system of four trench lines, the fourth trench being about 2,000 yards (1,800 m) from the British front line and to be reached at 8:18 a.m., 48 minutes after zero hour. The second objective was set at the German second intermediate line (Keisergraben) just short of Contalmaison and Pozières to be reached at 8:58 a.m. where the 101st and 102nd brigades were to dig in. The 103rd Brigade was then to pass through and reach the final objective on the far side of Contalmaison and Pozières at 10:10 a.m., and consolidate, ready to attack the German second position, 800 yards (730 m) further on.[30]

German defensive preparations

The German defences began with a front system which had four strong points in the southern section, Heligoland (Sausage Redoubt) backed by Scots Redoubt, Schwabenhöhe and La Boisselle.[31] The front defensive system was held by two battalions of Reserve Infantry Regiment 110 of the 28th (Baden) Reserve Division, with a third battalion in reserve in the intermediate lines and the second position.[32] On the far side of the road opposite the 8th Division the village of Ovillers had also been fortified. An intermediate line had been dug further back, from Fricourt Farm to Ovillers and a second intermediate line was being dug in front of Contalmaison and Pozières. Behind this front position, a second position with two parallel trenches, had been built from Bazentin-le-Petit to Mouquet Farm. A third position had been dug about 3 miles (4.8 km) behind the second position. The front position lay on a forward slope, which could be seen from the British lines, except Granathof (Grenade Farm), the crater field just west of La Boisselle. The front position lay across several salients and re-entrants, the main ones being those at La Boisselle and Thiepval on higher ground to the north. The Bapaume–Albert road descended westwards from Pozières then down the north side of the La Boisselle spur as far as the front lines, then beyond to Albert.[31] On 29 June, a heavy shell destroyed the command post of Colonel von Vietinghoff, the commander of Reserve Infantry Regiment 110, who was forced to withdraw to another post at Contalmaison.[33]

Battle

1 July

Right flank

At 7:30 a.m. on 1 July, the infantry of the 34th Division apart from the leading troops of the second column rose from their jumping-off trenches.[34] The leading battalions attacked from the front line and those at the rear moved down from the Tara–Usna ridge into the Avoca valley. Within ten minutes, 80% of the men in the leading battalions had become casualties from German machine-gun fire, which began as soon as the British bombardment lifted off the German front line. Many of the German machine-guns were in concealed positions behind the front line and had not been hit by the bombardment. Bullets swept no man's land, which was 200–800 yards (180–730 m) wide at this point and the forward slope of the Tara–Usna ridge, behind the British front line. As soon as the advance of the head of an attacking column was stopped, the rest of the column bunched up behind and made an easy target for the German defenders. The right-hand column had to advance along the convex slope on the west side of Fricourt Spur, for which the leading companies of the 15th (Service) Battalion (1st Edinburgh), The Royal Scots (Lothian Regiment) (15th Royal Scots) had advanced to within 200 yards (180 m) of the German front line, before zero hour.[35]

When the barrage lifted, the troops overran the German front trench on the higher part of the slope but German flanking fire from Sausage Valley and La Boisselle, forced the leading companies away from the north-east to due east on the right. The left flanking units of the rear companies and the 16th Royal Scots were shot down as they followed on. Parties of the 15th Royal Scots were left behind to attack Sausage Redoubt and the trenches in the vicinity, as the rest advanced straight up the slope straying into the XV Corps sector, held by the 21st Division. By 7:48 a.m. both battalions were atop the Fricourt Spur and Sausage and Scots redoubts were still occupied by German troops. The infantry advance continued for about 1 mile (1.6 km), before the error in navigation was realised thirty minutes later, at Birch Tree Wood beyond the sunken road into Fricourt, where 21st Division troops were encountered.[35] The British advance had taken place at the junction of Reserve Infantry regiments 110 and 111, separating two infantry companies.[36] The battalions then turned north, the 15th Royal Scots up Birch Tree Trench in the second intermediate line, towards Peake Woods, with the 16th Royal Scots in support along the Fricourt–Pozieres road, 200 yards (180 m) behind. A company of the reserve battalion of Reserve Infantry Regiment 110 counter-attacked from Peake Woods, throwing hand-grenades and German troops in Scots Redoubt and the third and fourth trenches behind the Scots, engaged them with machine-gun fire.[37]

The German attack inflicted many casualties and forced the 15th Royal Scots back to Birch Tree Wood, Shelter Wood and repulsed the 16th Royal Scots and parties from the second column, to Round Wood. The Scots then began an advance to Wood Alley and Scots Redoubt, incorporating parties separated from other units and captured both positions.[37] Some of the Royal Scots had advanced beyond the first objective and faced the Contalmaison Spur 1,000 yards (910 m) beyond. German accounts recorded that a party of the 16th Royal Scots got into the village of Contalmaison before being annihilated. The 27th Northumberland Fusiliers (27th Northumberland) which had followed behind the Royal Scots, had been pinned down in no man's land by massed machine-gun fire. Small groups had managed to press on to the Fricourt–Pozières road and some parties accompanied by a few 24th Northumberland from the left-hand brigade column got to Acid Drop Copse and the fringe of Contalmaison. As news filtered back, Gore sent the 16th Royal Scots headquarters forward to take command and the positions gained were consolidated, creating a defensive flank for the XV Corps.[38]

The brigade column on the left advanced five minutes after the rest of the division, to avoid debris from the Lochnagar mine and because the German line to the south curved back around Sausage Valley. The mine was sprung on time at 7:28 a.m. and left a crater 270 feet (82 m) wide, 210 feet (64 m)deep and with lips 15 feet (4.6 m) above ground level, killing most of the 5th Company of Reserve Infantry Regiment 110.[39][36] The delay was unnecessary and the column had a greater distance to advance than the third brigade column to the left.[Note 1] With the column behind the two on either side, German troops had more time to get ready in the trenches and in Sausage Redoubt (Heligoland), where the north face was on the flank of the column advance. Small-arms fire from Sausage Redoubt, the trenches nearby in Sausage Valley and from La Boisselle, which had hit the right-hand column, was turned on to the second column and within two minutes the 10th (Service) Battalion Royal Lincolnshire Regiment (the Grimsby Chums) and the 11th (Service) Battalion Suffolk Regiment had been raked by machine-gun fire, before they had got beyond the British front line and the 11th Suffolk was also bombarded by German artillery.[38]

Only isolated parties crossed no man's land and those on the right which attacked Sausage Redoubt, were burnt on the parapet by flame throwers. Some troops of the 11th Suffolk managed to advance and join the first brigade column survivors on the Fricourt Spur but most of the first two battalions were unable to cross no man's land and the 24th Northumberland was held back in the British front line, although some troops had set off before the order arrived. The troops took what cover existed in no man's land and some of the men from the three battalions in the column, reached the crater of Lochnagar mine and dug in. A counter-attack from the 4th Company of Reserve Infantry Regiment 110, forced British troops back to the crater by midday.[36] The party from the right-hand column left behind to capture Sausage Redoubt, tried to bomb towards it but were repulsed and two attempts by a Field Company RE and a company of the 18th Northumberland (Pioneers) Battalion to cross no man's land failed and the brigade column had to lie in no man's land and wait for dark.[41]

Left flank

The first of the 102nd Brigade columns, with the 21st and 22nd Northumberland supported by the 26th Northumberland of the 103rd Brigade, had tried to advance on the north side of the Lochnagar crater blown under Schwabenhöhe and just south of La Boisselle. The column advanced as the mine was sprung and having only 200 yards (180 m) of no man's land to cross, managed to overrun Schwabenhöhe and advance along the west side of Sausage Valley just below the village. The troops get beyond the Kaufmanngraben and Alte Jägerstrasse trenches but the right flank was unsupported due to the disaster to the brigade column on the right. Parties of bombers attacked towards La Boisselle but were stopped by the garrison, despite the Stokes mortar bombardment on the village, which had been falling for twelve minutes, to cover the 102nd Brigade columns as they moved past. As soon as the garrison emerged unharmed from deep shelters under the village, they engaged the third column with machine-guns and enfiladed the British infantry, as they tried to move past and caused many casualties to all three battalions.[42] The surviving troops still managed to reach Quergraben III, the first intermediate line across the Contalmaison road and some men reached Bailiff Wood, 500 yards (460 m) from Contalmaison village. German counter-attacks by an improvised unit of runners, telephonists and pioneers, near a battery of Reserve Field Artillery Regiment 28, were made on the Völkerbereitschaft.[36] The 22nd Northumberland was forced back to Kaufmanngraben, where about 200 men dug in along 400 yards (370 m) of trench.[42]

The fourth brigade column, with the 20th Northumberland and 23rd Northumberland of the 102nd Brigade and the 25th Northumberland of the 103rd Brigade, was to pass beyond the Glory Hole and north of La Boisselle. The German front line followed the contours of Mash Valley north of the La Boisselle Spur, which was 800 yards (730 m) east of the British front line. Y Sap Mine was exploded on time but as soon as the advance began, the column was engaged by German machine-gunners in La Boisselle and Ovillers and also received some artillery-fire.[Note 2] The leading battalions kept going but almost all of the troops were shot down in no man's land, although some managed to reach the second trench before being killed. The flanking parties were repulsed from the village and the 25th Northumberland in the rear was also cut down in no man's land, most of the battalion and brigade staffs becoming casualties too. The survivors of the fourth brigade column withdrew to the British front line. Thick smoke and dust obscured the view of 34th Division observers and until 9:00 a.m. exaggerated reports of success had been believed and some field artillery was ordered to advance. No troops were in reserve to resume the attack and at 11:25 a.m. a battalion of the 19th Division was sent forward but an attack by this battalion and the last company of the pioneer battalion was cancelled, two brigades of the 19th Division being sent forward to attack after dark instead.[44]

Troops near Sausage Redoubt (Heligoland), made attempts to capture the position and at 1:00 p.m. a bombardment was fired on the redoubt and adjacent trenches until 3:20 p.m., when a force from the 21st Division began to bomb north along the German front line, as a party from the 34th Division attacked southwards from the Lochnagar crater but the shell-fire had no effect. The first line of troops from the crater, lost 23 of thirty men as soon as they advanced and the 21st Division troops were halted almost immediately. By nightfall, two communication trenches had been dug across no man's land, either side of the redoubt and another had been dug by the 21st Division, which gave access to the Royal Scots at Birch Tree and Round woods. On the left flank, three tunnels which had been dug before the attack and one was used as a covered way, to reach the Tyneside Scottish in the German defences south of La Boisselle and supply water, food and ammunition, which enabled the footholds to be held.[Note 3] The remaining troops of the 10th Lincolns and the 11th Suffolk managed to retire during the night to the front line, where they were later relieved by the 19th Division.[45] A night attack by the 19th Division, due to begin at 10:30 p.m. was cancelled as the 57th and 58th brigades were not able to get forward, over ground which had been churned by the bombardment and was covered with the dead of the morning attack; communications trenches were found to be full of walking-wounded and stretcher bearers.[46]

2 July

By dawn the 9th Cheshires of the 58th Brigade (Brigadier-General A. J. W. Dowell) had arrived at Schwabenhöhe and relieved the 34th Division troops. An attack by the 58th Brigade only was ordered for 4:00 p.m. as the 57th Brigade was still moving up. The German defenders had ceased firing and supplies were easily moved across no man's land to the two footholds and two companies of the 7th East Lancs of the 56th Brigade (Brigadier-General F. G. M. Rowley) were given to the 34th Division, to attack Sausage Redoubt.[47] At 5:10 a.m. the 26th Reserve Division headquarters ordered that Reserve Infantry Regiment 110 was to retire through La Boisselle and that Ovillers was to be held to the last man.[48] The companies advanced across 500 yards (460 m) of no man's land in the afternoon and bombed into the redoubt, then carried on to trenches beyond and consolidated a line about 1,000 yards (910 m) wide, having taken 58 prisoners.[49] As a ruse, the 58th Brigade attack was preceded by a bombardment on Ovillers from 3:30–4:00 p.m. and a smoke screen released at zero hour. The deception succeeded and German artillery fired on Ovillers but not La Boisselle, where a frontal attack was made by the 6th Wiltshire and the 9th Royal Welch Fusiliers (9th RWF). The attackers got across no man's land and captured the German front line trench with few casualties and the rest of the 9th Cheshire attacked on the right. As the Germans recovered from the surprise, resistance increased and the British systematically searched for and bombed the German underground shelters. The area was visible from the British lines and artillery support enabled the infantry to occupy the west end of the village by 9:00 p.m. and dig in near the church.[46]

3 July

During an attack on Ovillers by the 12th Division, which had relieved the remnants of the 8th Division, a company strayed southwards towards La Boisselle and trapped 220 German troops, who surrendered and were handed over to the 19th Division. The 57th Brigade had moved up on the left of the 58th Brigade and at 2:15 a.m. the 8th (Service) Battalion, The Prince of Wales's (North Staffordshire Regiment) and bombers of the 5th South Wales Borderers (Pioneers) attacked between La Boisselle and the Albert–Bapaume road, with the 10th Worcesters on the left flank. At 3:15 a.m. both brigades attacked, to advance beyond the village to a trench 400 yards (370 m) and gain touch with the divisions on the flanks. By bombing and fighting hand-to-hand, the British gradually drove the remnants of Reserve Infantry 110 and reinforcements from Infantry Regiment 23 from the village and took 123 prisoners. The underground fortifications in the village had withstood the recent bombardments and attempts to signal with flares that the village has been captured led to the German artillery bombarding the village with howitzers and mortars, followed by a counter-attack by Infantry Regiment 190 of the 185th Division, which drove the British back from the east end of the village. Reinforcements from the 10th Warwicks and 8th Gloucestershire went forward and eventually a line was stabilised through the church ruins, about 100 yards (91 m) beyond the start line of the British attack. The 34th Division troops on the right flank of the corps area, tried to link with the 19th Division but after three attacks stopped the attempt. After dark the 23rd Division began to relieve the 34th Division with the 69th Brigade.[50][Note 4]

4–6 July

Rain fell during the night of 3/4 July and showers during the day ended in a thunderstorm all afternoon. Troops were soaked, trenches flooded and the ground turned to deep mud and clung to boots and hooves; the RFC was mostly grounded but managed to register some artillery and reconnoitre Mametz Wood. At 8:30 a.m. the 56th Brigade of the 19th Division attacked at La Boisselle with the 7th King's Own, which bombed up trenches with covering fire from machine-guns and Stokes mortars. Determined resistance by the German defenders held back the British until 2:30 p.m. when all but some ruins at the north end had been captured. The 23rd Division attacked towards the 19th Division at 4:00 a.m. with bombing parties from the 9th Green Howards and fighting at Horseshoe Trench went on until 10:00 a.m. when a German counter-attack forced the British back. Another counter-attack in the afternoon led to most of the 69th Brigade being sent forward.[52] Around 6:00 p.m. attacked over the open and captured Horseshoe Trench and Lincoln Redoubt. The 19th Division attacked at the east side of La Boisselle but the bombers were repulsed. The 1st Sherwood Foresters arrived from the 23rd Division as a reinforcement but the 9th Colberg (Graf Gneisenau) (2nd Pomeranian) Grenadiers of the 3rd Guard Division also arrived and neither side managed to advance; during the night the 12th Division relieved the 57th Brigade at La Boisselle. The area between the 23rd Division on the right and the 19th Division around La Boisselle was attacked at 7:30 p.m. by bombing parties of the 7th East Lancs, was repulsed but a second attack over the open succeeded, after which three German counter-attacks were defeated.[53]

Air operations

The explosion of the Lochnagar and Y Sap mines was witnessed from the air by 2nd Lieutenant C.A. Lewis of 3 Squadron, flying a Morane Parasol;

At Boisselle the earth heaved and flashed, a tremendous and magnificent column rose up in the sky. There was an ear-splitting roar drowning all the guns, flinging the machine sideways in the repercussing air. The earth column rose higher and higher to almost 4,000 feet (1,200 m). There it hung, or seemed to hang, for a moment in the air, like the silhouette of some great cypress tree, then fell away in a widening cone of dust and debris. A moment later came the second mine. Again the roar, the upflung machine, the strange gaunt silhouette invading the sky. Then the dust cleared and we saw the two white eyes of the craters. The barrage had lifted to the second-line trenches, the infantry were over the top, the attack had begun.[54]— Cecil Lewis

aircraft of 3 Squadron flew over the III Corps sector and observers reported that the 34th Division had reached Peake Wood on the right flank, increasing the size of the salient driven into the German lines north of Fricourt. The villages of La Boisselle and Ovillers had not fallen. On 3 July, air observers noted flares lit in the village during the evening, which were used to plot the positions reached by British infantry.[55]

Aftermath

Analysis

In the days after 1 July, it was found that the bombardment had not damaged the German minierte stollen and that at 2:45 a.m. on 30 June, a listening post equipped with a Moritz device, had eavesdropped a British telephone conversation, which made it certain that the attack was to begin the next day. The Moritz device operators overheard orders that the British infantry were to hold on to every yard of ground gained. The message had been sent by the Fourth Army headquarters on 30 June at 10:17 p.m.,

In wishing all ranks good luck the Army commander desires to impress on all infantry units the supreme importance of helping one another and holding on tight to every yard of ground gained. The accurate and sustained fire of the artillery during the bombardment should greatly assist the task of the infantry.[56]

The III Corps divisions had lost more than 11,000 casualties and had failed to capture La Boisselle or Ovillers; only small footholds had been gained on the XV Corps boundary and at Schwabenhöhe. The defences of Reserve Infantry Regiment 110 had been destroyed and dug-out entrances had only been kept open by constant digging. No German casualties were reported after the Y Sap mine detonation, as the defences nearby had been evacuated but Lochnagar mine caused great damage and delayed the survivors from emerging from dug-outs. Hand-to-hand fighting took place and the garrison was driven from Schwabenhöhe and the trench further back.[57]

In 2005, Prior and Wilson wrote that the task of III Corps was made difficult by the topography of the corps sector, since behind the British front there was no cover and that even small bodies of troops moving in daylight would attract massed machine-gun and artillery fire. La Boisselle and Ovillers across the road, had been fortified and entrenched, further north the Nordwerk and the Leipzig Salient in the X Corps area dominated the left of the III Corps sector,which left the 8th and 34th divisions dependent on the effectiveness of the X Corps bombardment. No man's land in the 34th Division sector varied from 200–800 yards (180–730 m) and Prior and Wilson wrote that they had found no particular attention had been given to the way that the infantry were to cross the wider parts. As the preliminary bombardment was fired, it was seen that the German infantry in the front line was still able to observe the British front line and fire on parties in no man's land. The 34th Division plan of attack committed all of the infantry battalions, which left no immediate reserve. The mines were expected to provide some protection against German machine-gun fire by creating mounds around the crater rims and a smoke screen was to cover La Boisselle at zero hour, although the wind blew it away from the village. Prior and Wilson criticised the bombardment plan for lifting the heavy artillery off the German front line at 7:00 a.m., thirty minutes before the infantry advance, which meant that its fire for the rest of the day was ineffective.[58]

Field artillery and field howitzers were left to suppress the German defenders for the last thirty minutes but had little destructive power against field fortifications. The advance towards Schwabenhöhe was to begin five minutes later than the rest of the brigade columns on either side which gave the Germans nearby time to recover. The German Moritz eavesdroppers who warned of the imminent attack, enabled the Germans to vacate the underground shelters near Y Sap in time and shoot down the infantry of the fourth brigade column. The Lochnagar mine blast had more effect and British troops gained a shallow foothold in the German defences in the vicinity and were able to hold on despite German counter-attacks. The advance of the 103rd Brigade was over ground with a fold, which meant that the disastrous attack by the preceding brigades could not be seen as the brigade was hit by artillery and machine-gun fire, which inflicted 70% casualties, before the troops had reached the British front line. Prior and Wilson wrote that the attack had gained a derisory amount of ground and that the condition of the 34th Division was reduced to the point that the 19th Division was rushed forward, in case of a German counter-attack on Albert. Prior and Wilson wrote that III Corps planning had been unimaginative, yet the failure of the artillery bombardment would have doomed any plan. The bombardment had been spread over too wide an area and against too many targets, which left the German front line garrisons mostly intact at zero hour, easily capable of defeating the attack.[59] In 2008, Harris called the III Corps attack an unmitigated disaster.[60]

Casualties

On 1 July, the 34th Division suffered the largest number of casualties of the British divisions engaged, losing 6,380 men. The 15th Royal Scots had 513 casualties and the 16th Royal Scots lost 466 men. The Grimsby Chums lost 477 men and the 15th Suffolks had 527 casualties.[61] In 1921, the 34th Division historian, J. Shakespear using records compiled just after the division was relieved, write that in three days, the 101st Brigade had lost 2,299 men, the 102nd Brigade had 2,324 casualties and the 103rd Brigade incurred 1,968 losses.[62] Wyrall, the 19th Division historian, wrote in 1932 that the capture of La Boisselle cost the division about 3,500 casualties and that c. 350 prisoners were taken.[63] Reserve Infantry Regiment 110 lost 1,251 men from 1–3 July.[64] In 2013, Whitehead calculated that Reserve Infantry Regiment 110 lost 58 men killed in the village and the right-hand defensive sectors on 1 July but could not give a figure for the wounded.[65]

Subsequent operations

On 7 July, in the III Corps area the 68th Brigade of the 23rd Division, was delayed by the barrage on Bailiff Wood until 9:15 a.m., when a battalion reached the southern fringe, before machine-gun fire from Contalmaison forced them back 400 yards (370 m), as a fresh battalion worked along a trench towards the 19th Division on the left flank. The attack on Contalmaison by the 24th Brigade was delayed until after 10:00 a.m., when two battalions attacked from Pearl Alley and Shelter Wood, Contalmaison being entered and occupied up to the church after a thirty-minute battle, in which several counter-attacks were repulsed but the attack from Shelter Wood failed. An attempt to attack again was cancelled due to the mud, a heavy German barrage and lack of fresh troops.[66] On the left the 19th Division bombers skirmished all day and at 6:00 p.m. a warning from an observer in a reconnaissance aircraft, led to an advance by German troops towards Bailiff Wood being ambushed and stopped by small-arms fire. An advance on the left flank, in support of a 12th Division attack on Ovillers, got forward about 1,000 yards (910 m) and reached the north end of Ovillers.[67]

On 9 July, the 23rd Division attacked south and west of Contalmaison and a German counter-attack by Infantry Regiment 183 of the 183rd Division at 4:30 p.m., was repulsed with many casualties. The British attacked again at 8:15 a.m. on 10 July and managed to occupy Bailiff Wood and trenches either side. After a thirty-minute bombardment, a creeping barrage moved in five short lifts through the village to the eastern fringe, as every machine-gun in the division fired on the edges of the village and the approaches. The attack moved forward in four waves, with mopping-up parties following, through return fire from the garrison and reached a trench at the edge of the village, forcing the survivors to retreat into Contalmaison. The waves broke up into groups which advanced faster than the barrage.[68] Only c. 100 troops of the I Battalion, Grenadier Regiment 9 made it back; the village was consolidated inside a "box barrage".[68]

1918

La Boisselle was captured by the Germans on 25 March 1918, during the retreat of the 47th Division and the 12th (Eastern) Division during Operation Michael, the German spring offensive.[69][70][71] In the afternoon, air reconnaissance saw that the British defence of the line from Montauban and Ervillers was collapsing and the RFC squadrons in the area made a maximum effort to disrupt the German advance.[72] The village and vicinity were recaptured for the last time on 26 August, by the 38th Division during the Second Battle of Bapaume.[73][74]

Gallery

-

La Boisselle mine crater, August 1916 (IWM Q 912) -

Troops passing Lochnagar Crater, October 1916 (IWM Q 1479) -

Lochnagar Crater, Ovillers -

Lochnagar crater -

Lochnagar mine

Notes

- ↑ Photographs taken during mine explosions earlier in the year, showed that material blown in the air and capable of causing injury, landed within twenty seconds. During the Actions of the St. Eloi Craters (27 March – 16 April) a delay of 30–60 seconds was planned but the infantry had attacked at zero hour anyway.[40]

- ↑ 36 German soldiers were rescued from a dug-out close to Y Sap and reported that nine other dug-outs nearer to the mine must have been collapsed.[43]

- ↑ The tunnel had been dug in the 34th Division area and two more in the 8th Division sector to the north. The tunnels were 8.5 feet (2.6 m) high, 3.5 feet (1.1 m) wide at the bottom and 2.5 feet (0.76 m) wide at the top, 12–14 feet (3.7–4.3 m) underground. The great secrecy maintained during the digging had delayed their use, as their existence was unknown to the attacking troops.[45]

- ↑ The 34th Division had lost 6,811 men from 1–5 July and the 102nd and 203rd brigades were swapped for the 111th and 112th brigades of the 37th Division until 21 August.[51]

Footnotes

- ↑ Gliddon 1987, p. 248.

- ↑ Philpott 2009, p. 28.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Sheldon 2005, pp. 22–26.

- ↑ Sheldon 2005, p. 38.

- ↑ Doughty 2005, pp. 46, 114.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 The Times 1916, p. 9.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Chtimiste 2003.

- ↑ Rogers 2010, pp. 57–58.

- ↑ Sheldon 2005, p. 56.

- ↑ Sheldon 2005, p. 62.

- ↑ The Times 1916, pp. 9, 39.

- ↑ Sheldon 2005, pp. 63–65.

- ↑ Wynne 1939, pp. 100–101.

- ↑ Whitehead 2010, p. 290.

- ↑ Wynne 1939, pp. 100–103.

- ↑ Philpott 2009, pp. 157–165.

- ↑ Edmonds 1932, pp. 316–317.

- ↑ Edmonds 1932, pp. 317–319.

- ↑ Gliddon 1987, p. 415.

- ↑ Edmonds 1932, pp. 371–372.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Edmonds 1932, pp. 372–373.

- ↑ Edmonds 1932, p. 38.

- ↑ Edmonds 1932, p. 375.

- ↑ Shakespear 1921, p. 37.

- ↑ Edmonds 1932, pp. 373–374.

- ↑ Edmonds & Wynne 1932, pp. 150–151.

- ↑ Edmonds 1932, p. 267.

- ↑ Edmonds 1932, p. 307.

- ↑ Edmonds 1932, pp. 375–376.

- ↑ Edmonds 1932, pp. 376–377.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Edmonds 1932, p. 372.

- ↑ Edmonds 1932, p. 376.

- ↑ Sheldon 2005, p. 158.

- ↑ Shakespear 1921, p. 39.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Edmonds 1932, pp. 377–378.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 Sheldon 2005, p. 159.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Edmonds 1932, pp. 378–379.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Edmonds 1932, pp. 379–380.

- ↑ Edmonds 1932, p. 379.

- ↑ Edmonds 1932, pp. 177–191, 430.

- ↑ Edmonds 1932, pp. 380–381.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Edmonds 1932, pp. 381–382.

- ↑ Edmonds 1932, p. 382.

- ↑ Edmonds 1932, pp. 382–383.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Edmonds 1932, p. 384.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Miles 1938, p. 7.

- ↑ Wyrall 1932, p. 240.

- ↑ Sheldon 2005, p. 186.

- ↑ Wyrall 1932, p. 41.

- ↑ Miles 1938, pp. 12–13.

- ↑ Miles 1938, p. 13.

- ↑ Miles 1938, pp. 20–21.

- ↑ Miles 1938, pp. 21–22.

- ↑ Lewis 1936, p. 90.

- ↑ Jones 1928, p. 212.

- ↑ Edmonds 1932, p. 392.

- ↑ Edmonds 1932, pp. 376, 391–392.

- ↑ Prior & Wilson 2005, pp. 92–93.

- ↑ Prior & Wilson 2005, pp. 93–99.

- ↑ Harris 2008, p. 231.

- ↑ Edmonds 1932, pp. 380–381, 391.

- ↑ Shakespear 1921, p. 52.

- ↑ Wyrall 1932, p. 47.

- ↑ Miles 1938, p. 12.

- ↑ Whitehead 2010, p. 306.

- ↑ Miles 1938, pp. 33–34.

- ↑ Miles 1938, pp. 40–41.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 Miles 1938, pp. 54–57.

- ↑ Edmonds, Davies & Maxwell-Hyslop 1935, pp. 480–481.

- ↑ Maude 1922, pp. 163–165.

- ↑ Middleton Brumwell 1923, pp. 169–170.

- ↑ Jones 1934, pp. 319.

- ↑ Edmonds 1947, pp. 238–242.

- ↑ Munby 1920, p. 51.

References

- Books

- Doughty, R. A. (2005). Pyrrhic Victory: French Strategy and Operations in the Great War. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University. ISBN 0-67401-880-X.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1932). Military Operations France and Belgium, 1916: Sir Douglas Haig's Command to the 1st July: Battle of the Somme. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence I (IWM & Battery Press 1993 ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-89839-185-7.

- Edmonds, J. E.; Wynne, G. C. (1932). Military Operations France and Belgium 1916: Appendices. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence I (Naval & Military Press 2010 ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 1-84574-730-5.

- Edmonds, J. E.; Davies, H. R.; Maxwell-Hyslop, R. G. B. (1935). Military Operations France and Belgium 1918: The German March Offensive and its Preliminaries. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence I (IWM and Battery Press 1995 ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-89839-219-5.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1947). Military Operations France and Belgium 1918: 8th August – 26th September The Franco-British Offensive. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence IV (IWM and Battery Press 1993 ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 0-89839-191-1.

- Gliddon, G. (1987). When the Barrage Lifts: A Topographical History and Commentary on the Battle of the Somme 1916. Norwich: Gliddon Books. ISBN 0-947893-02-4.

- Harris, J. P. (2008). Douglas Haig and the First World War (2009 ed.). Cambridge: CUP. ISBN 978-0-521-89802-7.

- Jones, H. A. (1928). The War in the Air, Being the Story of the Part Played in the Great War by the Royal Air Force (PDF) II (N & M Press 2002 ed.). London: Clarendon Press. ISBN 1-84342-413-4. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- Jones, H. A. (1934). The War in the Air Being the Part Played in the Great War by the Royal Air Force (PDF). History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence IV (N & M Press 2002 ed.). London: Clarendon Press. ISBN 1-84342-415-0. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- Lewis, C. A. (1936). Sagittarius Rising: The Classic Account of Fying in the First World War (2nd Penguin 1977 ed.). London: Peter Davis. ISBN 0-14-00-4367-5. OCLC 473683742.

- Maude, A. H. (ed.) (1922). The 47th (London) Division, 1914–1919 by Some who Served with it in the Great War. London: Amalgamated Press. OCLC 494890858. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- Middleton Brumwell, P. (1923). Scott, A. B., ed. History of the 12th (Eastern) Division in the Great War, 1914–1918 (N & M Press 2001 ed.). London: Nisbet. ISBN 1-84342-228-X. OCLC 6069610. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- Miles, W. (1938). Military Operations France and Belgium, 1916, 2nd July 1916 to the End of the Battles of the Somme. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence II (IWM & Battery Press 1992 ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-901627-76-3.

- Munby, J. E. (ed.) (1920). A History of the 38th (Welsh) Division: by the GSO's.I of the Division (M & M Press 2003 ed.). London: Hugh Rees. ISBN 1-84342-583-1. OCLC 495191912. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- Philpott, W. (2009). Bloody Victory: The Sacrifice on the Somme and the Making of the Twentieth Century. London: Little, Brown. ISBN 978-1-4087-0108-9.

- Prior, R.; Wilson, T. (2005). The Somme. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10694-7.

- Rogers (ed.), D. (2010). Landrecies to Cambrai: Case Studies of German Offensive and Defensive Operations on the Western Front 1914–17. Solihull: Helion. ISBN 978-1-906033-76-7.

- Shakespear, J. (1921). The Thirty-Fourth Division, 1915–1919: The Story of its Career from Ripon to the Rhine (N & M Press 2001 ed.). London: H. F. & G. Witherby. ISBN 1-84342-050-3. OCLC 6148340. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- Sheldon, J. (2005). The German Army on the Somme 1914–1916 (Pen & Sword Military 2006 ed.). London: Leo Cooper. ISBN 1-84415-269-3.

- Whitehead, R. J. (2010). The Other Side of the Wire: The Battle of the Somme. With the German XIV Reserve Corps, 2 July 1916 (2013 ed.). Solihull: Helion. ISBN 978-1-907677-12-0.

- Wynne, G. C. (1939). If Germany Attacks: The Battle in Depth in the West (Greenwood Press 1976 ed.). London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 0-8371-5029-9.

- Wyrall, E. (1932). The Nineteenth Division 1914–1918 (N & M Press 2009 ed.). London: Edward Arnold. ISBN 1-84342-208-5.

- Encyclopaedias

- The Times History of the War (PDF) VI. London: The Times. 1916. OCLC 642276. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- Websites

- Chtimiste, Le (2003). "La reprise de l’offensive fin 1914–début 1915". Historiques des Régiments 14/18 (in French). Retrieved 19 October 2014.

Further reading

- Books

- Edmonds, J. E. (1925). Military Operations, France and Belgium: Mons, the Retreat to the Seine, the Marne and the Aisne, August – October 1914. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan. OCLC 604621263.

- Sandilands, H. R. (1925). The 23rd Division 1914–1919 (N & M Press 2003 ed.). Edinburgh: Wm. Blackwood. ISBN 1-84342-641-2.

- Sheffield, G. (2011). The Chief: Douglas Haig and the British Army. London: Aurum Press. ISBN 978-1-84513-691-8.

- Simpson, A. (2001). The Operational Role of British Corps Command on the Western Front 1914–18 (Spellmount 2005 ed.). London: London University. ISBN 1-86227-292-1.

- Websites

- Legg, J. "Lochnagar Mine Crater Memorial, La Boisselle, Somme Battlefields". www.greatwar.co.uk. Retrieved 18 May 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Capture of La Boisselle. |

- official site of the Lochnagar Crater

- La Boisselle Study Group

- Ovillers–La Boisselle photo essay

- Grimsby Roll of Honour, 1914–1919

- Ovillers & la Boiselle

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||