Capitulation of Tainan (1895)

| Capitulation of Tainan | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Japanese invasion of Taiwan (1895) | |||||||

Japanese troops land at Pa-te-chui, 10 October 1895 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| ? | ? | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| ? | ? | ||||||

The Capitulation of Tainan, on 21 October 1895, was the last act in the Japanese invasion of Taiwan. The capitulation ended the brief existence of the Republic of Formosa and inaugurated the era of Japanese colonial rule in Taiwan.

Background

After the Qing Empire signed the Treaty of Shimonoseki, officials on Taiwan opposed to the cession of Taiwan to Japan proclaimed an independent Republic of Formosa and raised forces in order to resist the impending Japanese invasion. On 6 June 1895, in the wake of the Imperial Japanese Army's successful landing and occupation of northern Taiwan, President Tang Ching-sung fled the island. On 26 June the former-Qing garrison commander and vice-president of the Republic of Formosa Liu Yung-fu announced his succession as head of government, and used his base in Tainan as the capital of the second republic.

The capture of Tainan now became a political as well as a strategic imperative for the Japanese. However, this proved to be easier said than done. Faced with growing resistance to their occupation, the Japanese were unable to advance immediately on Tainan. During the second phase of the campaign, from June to August, the Japanese secured central Taiwan by occupying Miaoli and Changhua. They then paused for a month, and only embarked on the third and final phase of the campaign, the advance on Tainan, in the second week of October.

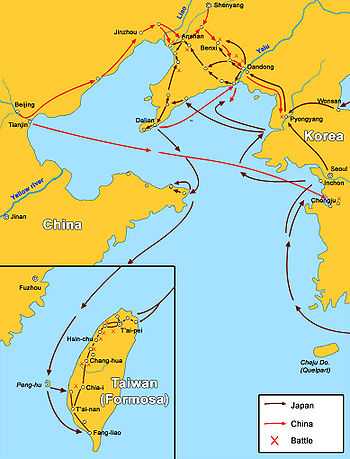

The arrival of strong reinforcements (the 2nd Provincial Division, transferred from the Japanese 2nd Army in Manchuria, and part of the 4th Provincial Division, from Osaka) allowed the Japanese to approach Tainan from three directions at once. On 10 October two task forces sailed from the Pescadores. The smaller task force, 5,460 troops under the command of Prince Fushimi, landed at Pa-te-chui (布袋嘴), to the north of Tainan. The larger task force, 6,330 troops under the command of Lieutenant-General Nogi, landed at Fangliao (枋寮), well to the south of Tainan. Its first objective was to capture the port of Takow (modern Kaohsiung), twenty-five miles to the north. Meanwhile, the Imperial Guards Division, then at Changhua, was ordered to continue to press forward towards Tainan. Just under 20,000 Japanese troops now closed in on Tainan simultaneously, from the north, the northeast and the south. Liu Yung-fu could probably field a larger force, but the Chinese and Formosans were by now fighting merely to stave off defeat. They had little hope of stemming the Japanese advance on Tainan.[1]

Japanese advance on Tainan

Japanese capture of Yunlin and Chiayi

The Imperial Guards Division commenced its march south from Changhua on 3 October. On 6 October the division’s advance guard defeated a force of 3,000 insurgents at Talibu. On 7 October the division fought an important action with the insurgents at Yunlin, driving them from a series of fortified positions. On 9 October the division fought the second-largest battle of the campaign, the Battle of Chiayi, to storm the walled city of Chiayi, where the insurgents had decided to make a determined stand. According to report, the Chinese and Formosans numbered 10,000 men and included both regular and volunteer units. The true figure was probably around 3,000 men, but the insurgents were stiffened by a force of 600 Black Flags, who now fought the Japanese for the first time during the campaign, and also deployed cannon and machine guns on the city walls. After a preliminary bombardment with their mountain artillery the Japanese scaled the walls and broke into the city. The insurgents were defeated, leaving over 200 dead on the field. Total casualties in the Imperial Guards Division in the engagements fought between 3 and 9 October were 14 killed and 54 wounded. The division was ordered to halt at Chiayi and wait until Prince Fushimi’s northern expedition went ashore at Pa-te-chui before resuming its advance.[2]

Liu Yung-fu's conditional surrender offer

On 10 October, discouraged by the news of the fall of Chiayi, Liu Yung-fu made an offer of conditional surrender to the Japanese. He asked that no Formosan should be punished for having taken up arms against the Japanese, and that all Chinese soldiers still in Taiwan should be treated hospitably and repatriated to Canton or Amoy. The surrender offer was conveyed to the Japanese headquarters at Makung in the Pescadores by the British warship HMS Pique, and the Japanese replied that they would send a warship to Anping, the outport of Tainan, on 12 October to discuss Liu's proposals. On 12 October the Japanese cruiser Yoshino arrived off Anping, but Liu Yung-fu refused to go aboard, perhaps fearing treachery. The Japanese subsequently informed him that they would accept only unconditional surrender.[3][4]

Japanese victory at Shau-lan

Meanwhile the other two Japanese columns were making their presence felt. Prince Fushimi's northern column, which included the 5th and 17th Infantry Regiments, landed at Pa-te-chui on 10 October. The division fought several brisk actions during its advance southwards. These included an action at Kaw-wah-tau on 12 October, in which Japanese casualties were slight, and an engagement near Kiu-sui-kei on 16 October to disengage a company of the 17th Regiment which had been surrounded by the insurgents, in which the Japanese suffered casualties of 9 dead and 10 wounded and the enemy at least 60 dead. On 18 October the 5th Infantry Regiment, supported by a battery of artillery and a troop of cavalry, routed the insurgents at Ongo-ya-toi. Japanese casualties were 3 dead and 14 wounded, while the enemy left 80 dead on the battlefield. On the same day the 17th Regiment met the Formosans at Tion-sha and inflicted a heavy defeat upon them. Formosan losses were computed at around 400 killed, while on the Japanese side only one officer was wounded. Meanwhile, the brigade’s advance guard dislodged an insurgent force numbering around 4,000 men and armed with repeating rifles from the village of Mao-tau, to the south of the So-bung-go River, but suffered relatively high casualties in doing so. On 19 October, in a battle to capture the fortified village of Shau-lan, the Japanese took a striking revenge. The 17th Regiment trapped a force of 3,000 insurgents inside the village and inflicted very heavy casualties on them when they stormed it. Nearly a thousand enemy bodies were counted after this massacre. Japanese losses were only 30 men killed or wounded, including 3 officers.[5]

Japanese capture of Takow

Lieutenant-General Nogi's southern column, consisting of 6,330 soldiers, 1,600 military coolies and 2,500 horses, landed at Fangliao on 10 October, and engaged a force of Formosan militiamen at Ka-tong-ka (茄苳腳), modern Chiatung (佳冬), on 11 October. The Battle of Chiatung was a Japanese victory, but the Japanese suffered their heaviest combat casualties of the campaign in the engagement—16 men killed and 61 wounded. Three officers were among the casualties. On 15 October Nogi's column closed in on the important port of Takow (Kaohsiung), but discovered that the Japanese navy had beaten it to the punch. Two days earlier, on 13 October, the Takow forts had been bombarded and silenced by the Japanese cruisers Yoshino, Naniwa, Akitsushima, Hiei, Yaeyama and Saien, and a naval landing force had been put ashore to occupy the town. Foiled of their prize, Nogi's men pressed on, and captured the town of Pithau (埤頭; modern-day Fongshan District) on 16 October. By 20 October they were at the village of Ji-chang-hang, only a few miles south of Tainan. There, on the night of 20 October, they received an offer of unconditional surrender from the Chinese merchants of Tainan.[6][7]

The collapse of the Republic of Formosa

Liu Yung-fu's flight

On 19 October, realising that the war was lost, Liu Yung-fu decided to leave for the Chinese mainland. Accompanied by around a hundred officers of the Tainan garrison, he left the city during the night on the pretence of going to inspect the defences of Anping. He then disguised himself as a coolie and boarded the British merchant ship Thales, bound for Amoy, on the morning of 20 October. The Japanese only got wind of Liu’s flight on the following morning, after they marched into Anping and Tainan, and on 21 October the Thales was pursued by the cruiser Yaeyama, halted fifteen miles from Amoy, and boarded by Japanese sailors. The Japanese sailors did not recognise Liu Yung-fu, but announced that they intended to arrest seven supposed Chinese labourers aboard the British vessel who were unable to give a satisfactory account of themselves. Although the Japanese did not know it, one of the seven labourers was Liu Yung-fu. He owed his escape to the intervention of the British captain. Indignant at being boarded on the high seas, the captain protested vigorously at this illegal search, and when the merchant ship reached Amoy all its passengers, including Liu Yung-fu, were allowed to go ashore without further hindrance. Admiral Arichi Shinanojo, the Japanese fleet commander in the invasion of Formosa, was shortly afterwards forced to resign as a result of a subsequent British complaint to Japan. Only later did the Japanese realise how close they had come to capturing Liu Yung-fu.[8][7]

The capitulation of Tainan

The news that Liu Yung-fu had abandoned the struggle broke in Tainan on the morning of 20 October. It was at first greeted with shock and disbelief. Soldiers and civilians alike wandered through the city’s streets, discussing this sudden turn of events in animated tones. Then the soldiers began to leave Tainan, making for the illusory safety of the port of Anping, a few miles further away from the Japanese lines. The Chinese merchants and the city’s small European community watched this development apprehensively. The mood of the soldiers could easily turn ugly, and there was a danger that they might return to plunder the city. For once, the European residents played a decisive part in events. Three European employees of the Maritime Customs at Anping—Messrs. Burton, McCallum and Alliston—persuaded the Chinese soldiers who had flocked to Anping to hand over their weapons for safekeeping and surrender peacefully to the Japanese. Nearly 10,000 Chinese soldiers rid themselves of their telltale firearms, and sat down to await events. The collection of the weapons lasted throughout the day, and by nightfall between 7,000 and 8,000 rifles had been secured and locked up in one of the godowns of the Maritime Customs.[9]

The next step was to invite the Japanese into Tainan. The Chinese merchants composed a suitable letter, swearing that all Chinese troops had laid down their arms and begging the Japanese to enter the city as soon as possible to maintain order. Nobody, however, was willing to run the considerable risks involved in delivering this message to the Japanese. Eventually two missionaries of the English Presbyterian Mission, James Fergusson and Thomas Barclay, agreed to make the perilous journey from Tainan to Lieutenant-General Nogi’s headquarters at Ji-chang-hang, a few miles south of the city. They set off just before nightfall, and made their way towards the Japanese front lines. After walking for a few hours they were halted by a rifle shot from a Japanese sentry, and were eventually brought into General Nogi’s presence. Nogi, unsurprisingly, was wary of possible Chinese treachery, but eventually decided to march on Tainan that night and enter the city early the following morning.[10][7]

Barclay and Fergusson later related their adventure to William Campbell, another member of the English Presybterian Mission, who gave the following description of their tense ordeal:

The sun was just setting when all the needful preparations were made, but not an hour was to be lost; and, therefore, taking the stamped document with them, my colleagues went out from the Great South Gate on their errand of mercy. The stars were shining brightly, and stillness reigned everywhere, till the party was startled by the ping of a rifle, and the loud challenge of a Japanese sentry. Signals were made, but they were immediately surrounded, and led to the presence of General Nogi, who consulted with his officers, and afterwards informed the missionaries of the acceptance of the invitation they brought, and that the army would begin to move before daybreak, having Mr. Barclay with the nineteen Chinamen in front, and Mr. Fergusson with several officers marching in the rear. It was also plainly stated that, on the slightest show of treachery or resistance, the soldiers would open fire, and the whole city be burned to the ground. The time occupied by that long march back again was, indeed, an anxious one; and as the missionaries drew near and saw the city gates closed, their hearts sank within them lest some fatal interruption had taken place. That sound, too, seemed something more than the barking of dogs. Could it be possible that the roughs of the city had broken out at last, and were now engaged in their fiendish work? My colleagues looked behind, and saw only a wall of loaded rifles; in front, but there was no hopeful sign; and the strain was becoming almost insupportable, when the Great South Gate was swung wide open. Hundreds of gentry came forward bowing themselves to the ground, and in a minute more the flag of the Rising Sun was waving over the city.[11]

Nogi's column entered Tainan at 7 a.m. on 21 October, and by 9 a.m. had secured the city. The troops of Prince Fushimi’s northern column arrived on the afternoon of the same day. The capitulation of Tainan put an end to serious Formosan resistance and effectively inaugurated the era of Japanese colonial rule in Formosa.

Sources

Notes

- ↑ Takekoshi (1907), p. 89.

- ↑ Davidson (1903), pp. 358–9.

- ↑ Davidson (1903), pp. 361–2.

- ↑ Takekoshi (1907), pp. 89–90.

- ↑ Davidson (1903), pp. 359–61.

- ↑ Davidson (1903), pp. 354–8.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Takekoshi (1907), p. 90.

- ↑ Davidson (1903), pp. 363–4.

- ↑ Davidson (1903), p. 363.

- ↑ Davidson (1903), p. 364.

- ↑ Campbell (1915), pp. 283–4.

References

- Campbell, William (1915). Sketches from Formosa. London: Marshall Brothers. OL 7051071M.

- Davidson, James W. (1903). The Island of Formosa, Past and Present : history, people, resources, and commercial prospects : tea, camphor, sugar, gold, coal, sulphur, economical plants, and other productions. London and New York: Macmillan. OCLC 1887893. OL 6931635M.

- McAleavy, Henry (1968). Black Flags in Vietnam : The Story of a Chinese Intervention. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 9780049510142.

- Takekoshi, Yosaburō (1907). Japanese rule in Formosa. London, New York, Bombay and Calcutta: Longmans, Green, and co. OCLC 753129. OL 6986981M.

| ||||||||||||||||||||

.jpg)