Capital and corporal punishment in Judaism

The Jewish tradition describes certain forms of corporal punishment and capital punishment for certain crimes, while cautioning against the use of such punishments.

Capital punishment in classical sources

The harshness of the death penalty indicated the seriousness of the crime. Jewish philosophers argue that the whole point of corporal punishment was to serve as a reminder to the community of the severe nature of certain acts. This is why, in Jewish law, the death penalty is more of a principle than a practice. The numerous references to a death penalty in the Torah underscore the severity of the sin rather than the expectation of death. This is bolstered by the standards of proof required for application of the death penalty, which has always been extremely stringent (Babylonian Talmud Makkoth 7b). Because the standards of proof were so high, it was well-nigh impossible to inflict the death penalty. The Mishnah (tractate Makkoth 1:10) outlines the views of several prominent first-century CE Rabbis on the subject:

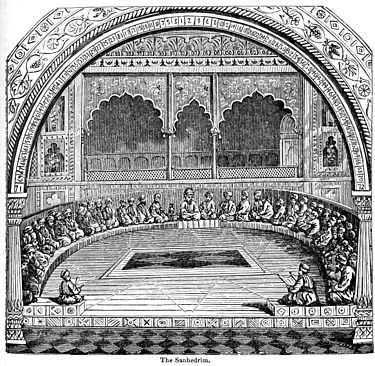

A Sanhedrin that puts a man to death once in seven years is called destructive. Rabbi Eliezer ben Azariah says that this extends to a Sanhedrin that puts a man to death even once in seventy years. Rabbi Akiba and Rabbi Tarfon say: Had we been in the Sanhedrin none would ever have been put to death. Rabban Simeon ben Gamaliel says: they would have multiplied shedders of blood in Israel.

The Sanhedrin stopped issuing capital punishment either after the Second Temple was destroyed in 70 CE or alternatively, according to passages in the Talmud and New Testament, in 30 CE when the Sanhedrin were moved out of the Hall of Hewn Stones. Other sources such as Josephus and other passages in the New Testament disagree. The issue is highly debated because of the relevancy to the New Testament trial of Jesus.[1][2] Ancient rabbis did not like the idea of capital punishment, and interpreted the texts in a way that made the death penalty virtually non-existent. The idea of killing someone for a crime they commit is frowned upon in the Jewish tradition.

The 12th-century Jewish legal scholar Maimonides stated that "It is better and more satisfactory to acquit a thousand guilty persons than to put a single innocent one to death." Maimonides argued that executing a defendant on anything less than absolute certainty would lead to a slippery slope of decreasing burdens of proof, until we would be convicting merely "according to the judge's caprice." Maimonides was concerned about the need for the law to guard itself in public perceptions, to preserve its majesty and retain the people's respect.[3]

Stringencies of evidence in capital cases

- It requires two witnesses who observed the crime. The accused would been given a chance and if repeated the same crime or any other it would lead into a death sentence. If witnesses had been caught lying about the crime they would be executed.

- Two witnesses were required. Acceptability was limited to:

- Adult Jewish men who were known to keep the commandments, knew the written and oral law, and had legitimate professions;

- The witnesses had to see each other at the time of the sin;

- The witnesses had to be able to speak clearly, without any speech impediment or hearing deficit (to ensure that the warning and the response were done);

- The witnesses could not be related to each other or to the accused.

- The witnesses had to see each other, and both of them had to give a warning (hatra'ah) to the person that the sin they were about to commit was a capital offense;

- This warning had to be delivered within seconds of the performance of the sin (in the time it took to say, "Peace unto you, my Rabbi and my Master");

- In the same amount of time, the person about to sin had to:

- Respond that s/he was familiar with the punishment, but they were going to sin anyway; AND

- Begin to commit the sin/crime;

- The Beth Din had to examine each witness separately; and if even one point of their evidence was contradictory - even if a very minor point, such as eye color - the evidence was considered contradictory and the evidence was not heeded;

- The Beth Din had to consist of minimally 23 judges;

- The majority could not be a simple majority - the split verdict that would allow conviction had to be at least 13 to 11 in favor of conviction;

- If the Beth Din arrived at a unanimous verdict of guilty, the person was let go - the idea being that if no judge could find anything exculpatory about the accused, there was something wrong with the court.[4]

- The witnesses were appointed by the court to be the executioners.

As a result, convictions for capital offense were rare in Judaism.[5][6]

The four types of capital punishment

Before any capital sentence was carried out, the condemned person was given a drug to render them senseless. There were four types of capital punishment, known as mitath beth din (execution by the rabbinic court). These four types of capital punishment, in decreasing severity, were:

- Sekila - stoning

- This was performed by pushing a person off a height of at least 2 stories. If the person didn't die, then the executioners (the witnesses) brought a rock that was so large that it took both of them to lift it; this was placed on the condemned person to crush them.

- Serefah - burning

- This was done by melting lead, and pouring it down the throat of the condemned person.

- Hereg - decapitation

- This is also known as "being put to the sword" (beheading).

- Chenek - strangulation

- A rope was wound around the condemned person's neck, and the executioners (the witnesses) pulled from either side to strangle the condemned person.

Capital sins separated by the four types of capital punishment

The following is a list by Maimonides in his Mishneh Torah (Hilchoth Sanhedrin Chapter 15) of which crimes carry a capital punishment.

Punishment by Sekila (stoning)

- Intercourse between a man and his mother.

- Intercourse between a man and his father's wife (not necessarily his mother).

- Intercourse between a man and his daughter in law.

- Intercourse with another man's wife from the first stage of marriage.

- Intercourse between two men.

- Bestiality.

- Cursing the name of God in God's name.

- Idol Worship.

- Giving one's progeny to Molech (child sacrifice).

- Necromantic Sorcery.

- Pythonic Sorcery.

- Attempting to convince another to worship idols.

- Instigating a community to worship idols.

- Witchcraft.

- Violating the Sabbath.

- Cursing one's own parent.

- A stubborn and rebellious son.

Punishment by Serefah (burning)

- The daughter of a priest who completed the second stage of marriage commits adultery.

- Intercourse between a man and his daughter.

- Intercourse between a man and his daughter's daughter.

- Intercourse between a man and his son's daughter.

- Intercourse between a man and his wife's daughter (not necessarily his own daughter).

- Intercourse between a man and his wife's daughter's daughter.

- Intercourse between a man and his wife's son's daughter.

- Intercourse between a man and his mother in law.

- Intercourse between a man and his mother in law's mother.

- Intercourse between a man and his father in law's mother.

Punishment by Hereg (beheading)

- Unlawful premeditated murder.

- Being a member of a city that has gone astray.

Punishment by Chenek (strangulation)

- Committing adultery with another man's wife, where it doesn't fall under the above criteria.

- Wounding one's own parent.

- Kidnapping another member of Israel.

- Prophesizing falsely.

- Prophesizing in the name of other deities.

- A sage who is guilty of insubordination in front of the grand court in the Chamber of the Hewn Stone.

Corporal punishment in classical sources

There was only one form corporal punishment - lashes (malkoth). The maximum number of lashes allowed per sentence was 40, given in multiples of 3, effectively making the maximum 39. Apart from as a punishment for violating Torah law, malkuth mardus (lashes of rebellion) was also administered in cases of contempt of court and violation of rabbinic law, where the court lashes the violator to the extent they see fit.

Contemporary attitudes towards capital punishment

Leading rabbis in Reform Judaism, Conservative Judaism, and Orthodox Judaism tend to hold that the death penalty is a correct and just punishment in theory, but they hold that it should not generally be used (or not used at all) in practice. In practice the application of such a punishment can only be carried out by humans whose system of justice is nearly perfect, a situation which has not existed for some time or never existed at all.

Rabbinical courts have given up the ability to inflict any kind of physical punishment, and such punishments are left to the civil court system to administer. But the modern institution of the death penalty is opposed by the major rabbinical organizations of Reform, Conservative, and Orthodox Judaism

Reform Judaism

Since 1959, the Central Conference of American Rabbis (CCAR) and the Union for Reform Judaism (URJ) have formally opposed the death penalty. The CCAR resolved in 1979 that "both in concept and in practice, Jewish tradition found capital punishment repugnant" and there is no persuasive evidence "that capital punishment serves as a deterrent to crime."[7]

Conservative Judaism

In Conservative Judaism the death penalty was the subject of a responsum by its Committee on Jewish Law and Standards, which has gone on record as opposing the modern institution of the death penalty:

The Talmud ruled out the admissibility of circumstantial evidence in cases which involved a capital crime. Two witnesses were required to testify that they saw the action with their own eyes. A man could not be found guilty of a capital crime through his own confession or through the testimony of immediate members of his family. The rabbis demanded a condition of cool premeditation in the act of crime before they would sanction the death penalty; the specific test on which they insisted was that the criminal be warned prior to the crime, and that the criminal indicate by responding to the warning, that he is fully aware of his deed, but that he is determined to go through with it. In effect this did away with the application of the death penalty. The rabbis were aware of this, and they declared openly that they found capital punishment repugnant to them… There is another reason which argues for the abolition of capital punishment. It is the fact of human fallibility. Too often we learn of people who were convicted of crimes and only later are new facts uncovered by which their innocence is established. The doors of the jail can be opened, in such cases we can partially undo the injustice. But the dead cannot be brought back to life again. We regard all forms of capital punishment as barbaric and obsolete.—Rabbi Ben Zion Bokser, Statement on capital punishment, 1960. Proceedings of the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards 1927-1970, Volume III, pp. 1537-1538

Orthodox Judaism

Orthodox Rabbi Yosef Edelstein writes:

So, at least theoretically, the Torah can be said to be pro-capital punishment. It is not morally wrong, in absolute terms, to put a murderer to death… However, things look rather different when we turn our attention to the practical realization of this seemingly harsh legislation. You may be aware that it was exceedingly difficult, in practice, to carry out the death penalty in Jewish society... I think it's clear that with regard to Jewish jurisprudence, the capital punishment outlined by the Written and Oral Torah, and as carried out by the greatest Sages from among our people (who were paragons of humility and humanity and not just scholarship, needless to say), did not remotely resemble the death penalty in modern America (or Texas). In theory, capital punishment is kosher; it's morally right, in the Torah's eyes. But we have seen that there was great concern—expressed both in the legislation of the Torah, and in the sentiments of some of our great Sages — regarding its practical implementation. It was carried out in ancient Israel, but only with great difficulty. Once in seven years; not 135 in five and a half.—Rabbi Yosef Edelstein, Director of the Savannah Kollel

Orthodox Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan writes:

In practice, however, these punishments were almost never invoked, and existed mainly as a deterrent and to indicate the seriousness of the sins for which they were prescribed. The rules of evidence and other safeguards that the Torah provides to protect the accused made it all but impossible to actually invoke these penalties… the system of judicial punishments could become brutal and barbaric unless administered in an atmosphere of the highest morality and piety. When these standards declined among the Jewish people, the Sanhedrin… voluntarily abolished this system of penalties.

See also

References

- ↑ https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/judaica/ejud_0002_0004_0_03929.html

- ↑ Watson E. Mills, Roger Aubrey Bullard, ed. (1990). Mercer Dictionary of the Bible. Mercer University Press. p. 795.

- ↑ Moses Maimonides, The Commandments, Neg. Comm. 290, at 269-271 (Charles B. Chavel trans., 1967).

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Sanhedrin, page 17a. Also Maimonidies, Mishneh Torah, Sanhedrin, Chapter 9.

- ↑ Mishnah Maccot, 1:10

- ↑ "讚讬谞讬 谞驻砖讜转". cet.ac.il.

- ↑ "Position of the Reform Movement on the Death Penalty". Religious Action Center.