Canonical correlation

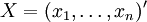

In statistics, canonical-correlation analysis (CCA) is a way of making sense of cross-covariance matrices. If we have two vectors X = (X1, ..., Xn) and Y = (Y1, ..., Ym) of random variables, and there are correlations among the variables, then canonical-correlation analysis will find linear combinations of the Xi and Yj which have maximum correlation with each other.[1] T. R. Knapp notes "virtually all of the commonly encountered parametric tests of significance can be treated as special cases of canonical-correlation analysis, which is the general procedure for investigating the relationships between two sets of variables."[2] The method was first introduced by Harold Hotelling in 1936.[3]

Definition

Given two column vectors  and

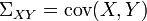

and  of random variables with finite second moments, one may define the cross-covariance

of random variables with finite second moments, one may define the cross-covariance  to be the

to be the  matrix whose

matrix whose  entry is the covariance

entry is the covariance  . In practice, we would estimate the covariance matrix based on sampled data from

. In practice, we would estimate the covariance matrix based on sampled data from  and

and  (i.e. from a pair of data matrices).

(i.e. from a pair of data matrices).

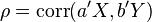

Canonical-correlation analysis seeks vectors  and

and  such that the random variables

such that the random variables  and

and  maximize the correlation

maximize the correlation  . The random variables

. The random variables  and

and  are the first pair of canonical variables. Then one seeks vectors maximizing the same correlation subject to the constraint that they are to be uncorrelated with the first pair of canonical variables; this gives the second pair of canonical variables. This procedure may be continued up to

are the first pair of canonical variables. Then one seeks vectors maximizing the same correlation subject to the constraint that they are to be uncorrelated with the first pair of canonical variables; this gives the second pair of canonical variables. This procedure may be continued up to  times.

times.

Computation

Derivation

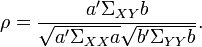

Let  and

and  . The parameter to maximize is

. The parameter to maximize is

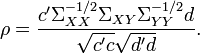

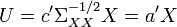

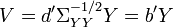

The first step is to define a change of basis and define

And thus we have

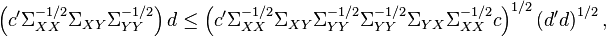

By the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality, we have

There is equality if the vectors  and

and  are collinear. In addition, the maximum of correlation is attained if

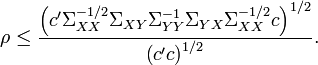

are collinear. In addition, the maximum of correlation is attained if  is the eigenvector with the maximum eigenvalue for the matrix

is the eigenvector with the maximum eigenvalue for the matrix  (see Rayleigh quotient). The subsequent pairs are found by using eigenvalues of decreasing magnitudes. Orthogonality is guaranteed by the symmetry of the correlation matrices.

(see Rayleigh quotient). The subsequent pairs are found by using eigenvalues of decreasing magnitudes. Orthogonality is guaranteed by the symmetry of the correlation matrices.

Solution

The solution is therefore:

-

is an eigenvector of

is an eigenvector of

-

is proportional to

is proportional to

Reciprocally, there is also:

-

is an eigenvector of

is an eigenvector of

-

is proportional to

is proportional to

Reversing the change of coordinates, we have that

-

is an eigenvector of

is an eigenvector of

-

is an eigenvector of

is an eigenvector of

-

is proportional to

is proportional to

-

is proportional to

is proportional to

The canonical variables are defined by:

Implementation

CCA can be computed using singular value decomposition on a correlation matrix.[4] It is available as a function in[5]

- MATLAB as canoncorr

- R as cancor or in FactoMineR

- SAS as proc cancorr

- Scikit-Learn, Python as Cross decomposition

Hypothesis testing

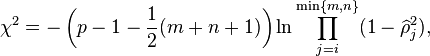

Each row can be tested for significance with the following method. Since the correlations are sorted, saying that row  is zero implies all further correlations are also zero. If we have

is zero implies all further correlations are also zero. If we have  independent observations in a sample and

independent observations in a sample and  is the estimated correlation for

is the estimated correlation for  . For the

. For the  th row, the test statistic is:

th row, the test statistic is:

which is asymptotically distributed as a chi-squared with  degrees of freedom for large

degrees of freedom for large  .[6] Since all the correlations from

.[6] Since all the correlations from  to

to  are logically zero (and estimated that way also) the product for the terms after this point is irrelevant.

are logically zero (and estimated that way also) the product for the terms after this point is irrelevant.

Practical uses

A typical use for canonical correlation in the experimental context is to take two sets of variables and see what is common amongst the two sets. For example in psychological testing, you could take two well established multidimensional personality tests such as the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI-2) and the NEO. By seeing how the MMPI-2 factors relate to the NEO factors, you could gain insight into what dimensions were common between the tests and how much variance was shared. For example you might find that an extraversion or neuroticism dimension accounted for a substantial amount of shared variance between the two tests.

One can also use canonical-correlation analysis to produce a model equation which relates two sets of variables, for example a set of performance measures and a set of explanatory variables, or a set of outputs and set of inputs. Constraint restrictions can be imposed on such a model to ensure it reflects theoretical requirements or intuitively obvious conditions. This type of model is known as a maximum correlation model.[7]

Visualization of the results of canonical correlation is usually through bar plots of the coefficients of the two sets of variables for the pairs of canonical variates showing significant correlation. Some authors suggest that they are best visualized by plotting them as heliographs, a circular format with ray like bars, with each half representing the two sets of variables.[8]

Examples

Let  with zero expected value, i.e.,

with zero expected value, i.e.,  . If

. If  , i.e.,

, i.e.,  and

and  are perfectly correlated, then, e.g.,

are perfectly correlated, then, e.g.,  and

and  , so that the first (and only in this example) pair of canonical variables is

, so that the first (and only in this example) pair of canonical variables is  and

and  . If

. If  , i.e.,

, i.e.,  and

and  are perfectly anticorrelated, then, e.g.,

are perfectly anticorrelated, then, e.g.,  and

and  , so that the first (and only in this example) pair of canonical variables is

, so that the first (and only in this example) pair of canonical variables is  and

and  . We notice that in both cases

. We notice that in both cases  , which illustrates that the canonical-correlation analysis treats correlated and anticorrelated variables similarly.

, which illustrates that the canonical-correlation analysis treats correlated and anticorrelated variables similarly.

Connection to principal angles

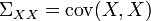

Assuming that  and

and  have zero expected values, i.e.,

have zero expected values, i.e.,  , their covariance matrices

, their covariance matrices ![\Sigma _{XX} =\operatorname{Cov}(X,X) = \operatorname{E}[X X']](../I/m/eeaa1bc71e861096ef61c2366b41b4d5.png) and

and ![\Sigma _{YY} =\operatorname{Cov}(Y,Y) = \operatorname{E}[Y Y']](../I/m/8891713be71187c704d1641af5bd5676.png) can be viewed as Gram matrices in an inner product for the entries of

can be viewed as Gram matrices in an inner product for the entries of  and

and  , correspondingly. In this interpretation, the random variables, entries

, correspondingly. In this interpretation, the random variables, entries  of

of  and

and  of

of  are treated as elements of a vector space with an inner product given by the covariance

are treated as elements of a vector space with an inner product given by the covariance  , see Covariance#Relationship_to_inner_products.

, see Covariance#Relationship_to_inner_products.

The definition of the canonical variables  and

and  is then equivalent to the definition of principal vectors for the pair of subspaces spanned by the entries of

is then equivalent to the definition of principal vectors for the pair of subspaces spanned by the entries of  and

and  with respect to this inner product. The canonical correlations

with respect to this inner product. The canonical correlations  is equal to the cosine of principal angles.

is equal to the cosine of principal angles.

See also

- Generalized Canonical Correlation

- Multilinear subspace learning

- RV coefficient

- Principal angles

- Principal component analysis

- Regularized canonical correlation analysis

- Singular value decomposition

- Partial least squares regression

References

- ↑ Härdle, Wolfgang; Simar, Léopold (2007). "Canonical Correlation Analysis". Applied Multivariate Statistical Analysis. pp. 321–330. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-72244-1_14. ISBN 978-3-540-72243-4.

- ↑ Knapp, T. R. (1978). "Canonical correlation analysis: A general parametric significance-testing system". Psychological Bulletin 85 (2): 410–416. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.85.2.410.

- ↑ Hotelling, H. (1936). "Relations Between Two Sets of Variates". Biometrika 28 (3–4): 321–377. doi:10.1093/biomet/28.3-4.321. JSTOR 2333955.

- ↑ Hsu, D.; Kakade, S. M.; Zhang, T. (2012). "A spectral algorithm for learning Hidden Markov Models". Journal of Computer and System Sciences 78 (5): 1460. arXiv:0811.4413. doi:10.1016/j.jcss.2011.12.025.

- ↑ Huang, S. Y.; Lee, M. H.; Hsiao, C. K. (2009). "Nonlinear measures of association with kernel canonical correlation analysis and applications". Journal of Statistical Planning and Inference 139 (7): 2162. doi:10.1016/j.jspi.2008.10.011.

- ↑ Kanti V. Mardia, J. T. Kent and J. M. Bibby (1979). Multivariate Analysis. Academic Press.

- ↑ Tofallis, C. (1999). "Model Building with Multiple Dependent Variables and Constraints". Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series D (The Statistician) 48 (3): 371–378. arXiv:1109.0725. doi:10.1111/1467-9884.00195.

- ↑ Degani, A.; Shafto, M.; Olson, L. (2006). "Canonical Correlation Analysis: Use of Composite Heliographs for Representing Multiple Patterns". Diagrammatic Representation and Inference. Lecture Notes in Computer Science 4045. p. 93. doi:10.1007/11783183_11. ISBN 978-3-540-35623-3.

External links

- Hardoon, D. R.; Szedmak, S.; Shawe-Taylor, J. (2004). "Canonical Correlation Analysis: An Overview with Application to Learning Methods". Neural Computation 16 (12): 2639–2664. doi:10.1162/0899766042321814. PMID 15516276.

- A note on the ordinal canonical-correlation analysis of two sets of ranking scores (Also provides a FORTRAN program)- in J. of Quantitative Economics 7(2), 2009, pp. 173-199

- Representation-Constrained Canonical Correlation Analysis: A Hybridization of Canonical Correlation and Principal Component Analyses (Also provides a FORTRAN program)- in J. of Applied Economic Sciences 4(1), 2009, pp. 115-124