Canadian raising

Canadian raising is a vowel shift in many dialects of North American English that changes the pronunciation of diphthongs with open-vowel starting points. Most commonly, the shift affects ![]() i/aɪ/ or

i/aɪ/ or ![]() i/aʊ/, or both, when they are pronounced before voiceless consonants (therefore, in words like

i/aʊ/, or both, when they are pronounced before voiceless consonants (therefore, in words like ![]() price and clout, respectively, but not in

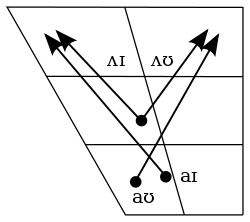

price and clout, respectively, but not in ![]() prize and cloud). In North American English, /aɪ/ and /aʊ/ usually begin in an open vowel, something like the vowel in alm [ä], but through raising they shift to a sound similar to the vowel in um: [ɐ] or [ʌ]. Canadian English often has raising in both the PRICE word set (including words like height, life, psych, type, etc.) and MOUTH word set (clout, house, south, scout, etc.), but most dialects in the United States have raising only in the PRICE word set.

prize and cloud). In North American English, /aɪ/ and /aʊ/ usually begin in an open vowel, something like the vowel in alm [ä], but through raising they shift to a sound similar to the vowel in um: [ɐ] or [ʌ]. Canadian English often has raising in both the PRICE word set (including words like height, life, psych, type, etc.) and MOUTH word set (clout, house, south, scout, etc.), but most dialects in the United States have raising only in the PRICE word set.

Americans popularly mock the raised Canadian pronunciation of about [əˈbɐʊt] or [əˈbəʊt], jokingly pronouncing it as a boot, though American a boat [əˈboʊt] is actually closer phonetically. Neither are completely accurate though, because about, a boot and a boat are distinct in all parts of Canada.

Similarly, the raising of /aɪ/ in North American English changes the first vowel in writer and causes it to be pronounced differently from the first vowel in rider. Since t and d in these words are pronounced the same through intervocalic alveolar flapping, these words are a minimal pair and are not complete homophones.

Description

|

Examples of Canadian raising in American English

rider, writer

[ɹäɪɾɚ] without raising, [ɹɐɪɾɚ] with it high school

bowed, bout

[ˈbäʊd] without raising, [ˈbəʊt] with it about, a boot, a boat

[əˈbɐʊt] with raising, compared with oo in [əˈbu̟t] and oh in [əˈbʌʊt] |

| Problems playing these files? See media help. | |

Phonetic environment

In general, Canadian raising affects vowels before voiceless consonants like /f/, /θ/, /t/, and /s/. Vowels before voiced consonants like /v/, /ð/, /d/, and /z/ are usually not raised.

This rule, however, is not completely accurate. A study of three speakers in Meaford, Ontario shows that pronunciation of the diphthong /aɪ/ falls on a continuum between raised and unraised. Raising is influenced by voicing of the following consonant, but it also appears to be influenced by the sound before the diphthong. Frequently the diphthong is raised when it is preceded by a coronal: in gigantic, dinosaur, and Siberia.[1]

Raising applies in compound words. Hence, high school [ˈhʌɪskul] as a term meaning "a secondary school for students approximately 14–18 years old" has raising of the vowel in high, whereas high school [ˈhaɪ ˈskul] with the literal meaning "a school that is high (e.g. in elevation)" is unaffected. (The two terms are also distinguished by the position of the stress accent, as shown).

Intervocalic alveolar flapping occurs in most dialects of North American English. Through this change, /t/ and /d/ between vowels are both pronounced as an alveolar flap [ɾ]. Alveolar flapping occurs after Canadian raising, so writer [ˈɹʌɪɾɚ] has a raised vowel and rider [ˈɹaɪɾɚ] does not, and these words are distinguished by their vowels, even though they both have a flapped [ɾ]. In British English, such as Received Pronunciation, neither flapping nor raising occur, so these words would have different consonants and identical vowels, except for a slight difference in length: [ˈɹaɪtə] and [ˈɹaɪdə].

Result

The raised variant of /aɪ/ typically becomes [ʌɪ], while the raised variant of /aʊ/ varies by dialect, with [ʌʊ] more common in Western Canada and a fronted variant [ɛʉ] commonly heard in Central Canada. In any case, the [a] component of the diphthong changes from a low vowel to a mid-low vowel ([ʌ], [ɐ] or [ɛ]).

Geographic distribution

Despite its name, Canadian raising is not restricted to Canada.

Raising of both /aɪ/ and /aʊ/ is common in eastern New England, for example in Boston (and the traditional accent of Martha's Vineyard), as well as in the Upper Midwest. South Atlantic English and the accents of Fens in England feature it as well.

Raising of just /aɪ/ is found in the northern half of the United States, including in the Inland North, New England, Philadelphia, and in some speakers of New York City English. It also appears in (especially northern) General American, California English, and other dialects of the Western United States, and it appears to be spreading. There is considerable variation in its application and phonetic effects.

In New York City English, /aɪ/ is backed in non-raised positions.[2] A dialect on the southern Atlantic coast raise /aʊ/ but not /aɪ/. There are also Canadians who raise /aɪ/ and not /aʊ/ or vice versa.

Possible origins

The most common understanding of the Great Vowel Shift is that the Middle English vowels [iː, uː] passed through a stage [əɪ, əʊ] on the way to their modern pronunciations [aɪ, aʊ]. Given its prevalence in areas of North America first settled by native English speakers, it is possible this is not an innovation of "raising" from an underlying vowel quality to another in the least, but, rather, of the preservation of an older vowel quality in a restricted environment.

References

Footnotes

Bibliography

- Britain, David (March 1997). "Dialect contact and phonological reallocation: "Canadian raising" in the English Fens". Language in Society 26 (1): 15–46. doi:10.1017/S0047404500019394. ISSN 0047-4045.

- Chambers, Jack (1973). "Canadian raising". Canadian Journal of Linguistics 18 (2): 113–35.

- Dailey-O'Cain, J. (1997). "Canadian raising in a midwestern US city". Language Variation and Change 9 (1): 107–120.

- Hall, Kathleen Currie (2005). Alderete, John; Han, Chung-hye; Kochetov, Alexei, eds. Defining Phonological Rules over Lexical Neighbourhoods: Evidence from Canadian Raising (PDF). West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Proceedings Project.

- Kaye, Jonathan (2012). "Canadian Raising, eh?". In Eugeniusz Cyran, Henryk Kardela, Bogdan Szymanek. Sound Structure and Sense: Studies in Memory of Edmund Gussmann. Lublin: Wydawnictwo KUL. pp. 321–352.

- Labov, W. (1963). "The social motivation of a sound change". Word (19): 273–309.

- Rogers, Henry (2000), The Sounds of Language: An Introduction to Phonetics, Essex: Pearson Education Limited, ISBN 978-0-582-38182-7

- Wells, John C. (1982). Accents of English. Cambridge University Press.