Canada–France Maritime Boundary Case

The Canada–France Maritime Boundary Case was a 1992 dispute between Canada and France that was decided by a court of arbitration which was created by the parties to resolve the dispute.[1] The case established the extent of the Exclusive Economic Zone of the French territory of Saint Pierre and Miquelon.[2]

Background

In 1972, Canada and France signed a treaty that delimited the territorial maritime boundary between Canada and the French territory of Saint Pierre and Miquelon. However, the maritime boundaries beyond the territorial sea (including extent of the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) of both countries) continued to be disputed. The extent of each country's EEZ was significant because it would determine where the countries had an exclusive right to fish. Years of failed negotiations led Canada and France to agree in March 1989 to establish an ad hoc arbitration court that would resolve the dispute.

Arbitration court

The arbitration court was composed of five arbitrators—three neutral parties and one representative from each country. The neutral arbitrators were Eduardo Jiménez de Aréchaga of Uruguay (president), Gaetano Arangio-Ruiz of Italy, and Oscar Schachter of the United States. Canada's representative was Allan Gotlieb and France's was Prosper Weil.

Decision

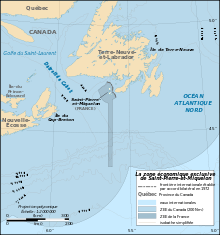

The arbitration court issued its decision and award on 10 June 1992. It was a 3–2 decision, with the representatives of both Canada and France dissenting from the decision. The zone that was awarded to France was unusual and in two parts: first, the boundary was set at an equidistant line between the French islands and the Canadian island of Newfoundland. Added to this was a 24 nautical mile bulge on the west of the islands. Lastly, a long north–south 188-nautical-mile (348 km) corridor south of the islands was awarded to France, presumably to allow France access to its EEZ from international waters without having to pass through the Canadian EEZ. The corridor is narrow, being approximately 10½ nautical miles wide. The shape of the award has been likened to a keyhole, a mushroom, and a baguette.[3]

The award was approximately 18% of the territory that France had initially been claiming.

Criticism

Since the 1992 award, the decision has been criticised by both Canadian and French commentators as well as neutral observers. Some have noted that a straightforward application of the Convention on the Law of the Sea would extend Canada's EEZ beyond the limits of the French corridor, meaning that the French EEZ may be entirely enveloped within Canada's EEZ, a circumstance that was not intended by the arbitation court.

Notes

- ↑ The case decision and the two dissents were printed in 31 International Legal Materials (ILM) 1149 (1992).

- ↑ Anderson, Ewan W. (2003). International Boundaries: A Geopolitical Atlas, p. 288; Charney, Jonathan I. et al. (2005). International Maritime Boundaries, pp. 2141–2158.

- ↑ Frank Jacobs (July 10, 2012). "Oh, (No) Canada!". Opinionator: Borderlines. The New York Times. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

References

- Anderson, Ewan W. (2003). International Boundaries: A Geopolitical Atlas. Routledge: New York. 10-ISBN 157958375X/13-ISBN 9781579583750; OCLC 54061586

- Charney, Jonathan I., David A. Colson, Robert W. Smith. (2005). International Maritime Boundaries, 5 vols. Hotei Publishing: Leiden. 10-ISBN 0792311876/13-ISBN 9780792311874; 10-ISBN 904111954X/13-ISBN 9789041119544; 10-ISBN 9041103457/13-ISBN 9789041103451; 10-ISBN 9004144617/13-ISBN 9789004144613; 10-ISBN 900414479X/13-ISBN 9789004144798; OCLC 23254092