Camulodunum

| CAMVLODVNVM | |

|---|---|

| Camulodunum | |

|

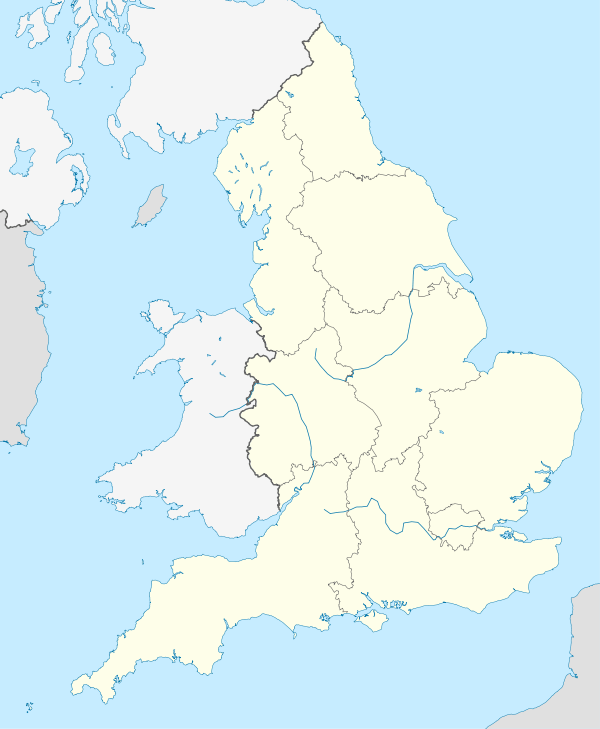

Colchester's Roman Town Walls | |

Shown within England | |

| Alternate name | Camulodunon, Colonia Claudia Victricensis, Colonia Victricensis |

| Location | Colchester, Essex, England |

| Region | Britannia |

| Coordinates | 51°53′31″N 0°53′53″E / 51.89194°N 0.89806°ECoordinates: 51°53′31″N 0°53′53″E / 51.89194°N 0.89806°E |

| Type | Colonia |

| History | |

| Founded | Late 1st century BC |

| Periods | British Iron Age to Roman Empire |

| Site notes | |

| OS grid reference: TL995255 | |

Camulodunum (/ˌkæmjʊloʊˈdjuːnəm/ or /ˌkæmʊloʊˈduːnəm/;[1] Latin: CAMVLODVNVM), the Ancient Roman name for what is now Colchester in Essex, was an important[2][3] town in Roman Britain, and the first capital of the province. It is claimed to be the oldest town in Britain.[4] Originally the site of the Celtic oppidum of Camulodunon (meaning "The Stronghold of Camulos"), capital of the Trinovantes and later the Catuvellauni tribes, it was first mentioned by name on coinage minted by the chieftain Tasciovanus sometime between 20 and 10BC.[5] The Roman town began life as a Roman Legionary base constructed in the AD40s on the site of the Celtic fortress following its conquest by the Emperor Claudius.[5] After the early town was destroyed during the Iceni rebellion in 60/1AD it was rebuilt, reaching its zenith in the Second and Third Centuries.[5] During this time it was known by its official name Colonia Claudia Victricensis (COLONIA CLAVDIA VICTRICENSIS),[6] often shortened to Colonia Victricensis, and as Camulodunum, a Latinised version of its original Celtic name.[7] The town was home to a large classical Temple, two theatres (including Britain's largest), several Romano-British temples, Britain's only known chariot circus, Britain's first town walls, several large cemeteries and over 50 known mosaics and tessallated pavements.[2][3][5][8] It may have reached a population of 30,000 at its height.[9] It wasn't until the late Eighteenth Century that historians realised that Colchester's physical Celtic and Roman remains were the city mentioned in ancient literature as "Camulodunum".[10]

Iron Age Camulodunon

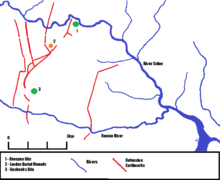

The earliest Iron Age defensive site at Colchester is the Pitchbury Ramparts earthwork north of the town near Braisewick.[5] The main earthwork defences of the Celtic oppidum of Camulodunon were built later, beginning in the First Century BC but most date from the First Century AD.[5] They are considered the most extensive of their kind in Britain.[5][11] The defences consist of lines of ditches and ramparts, possibly palisaded with gateways, that mostly run parallel to each other in a north-south direction. The Iron Age settlement was protected by rivers on three sides, with the River Colne bounding the site to the north and east, and the Roman River valley forming the southern boundary; the earthworks were mostly designed to close off the western gap between these two river valleys.[5][12] Other earthworks close off eastern parts of the settlement. These earthworks gave the oppidum its Celtic name - Camulodunon meant "The Stronghold of Camulus", the British God of War.[5]

The main sites within the bounds of these defences are the Gosbecks farmstead, the Sheepen industrial area and the Lexden burials. The Gosbecks site consists of a large, high-status farmstead,[7] believed to be the home of the tribal chieftains of Camulodunon.[5] Part of the Gosbecks complex is a large, square enclosure surrounded by a deep, wide ditch. This has been interpreted as part of a possible religious site, as during the Roman period a large temple was built in the middle of this enclosure.[5] The Sheepen site, located around what is now St Helena School on the banks of the River Colne, was a large industrial and port zone, where extensive iron and leather working activity was carried out,[5][12][13] as well as an important coin mint.[5] Two coins minted at Sheepen, one found in Colchester in 1980 and another found at Canturbury in 1978, depict boats, and are the only known depictions of sailing vessels from Iron Age Britain.[12] Amphorae containing imported goods from the continent have been found at Sheepen,[14] as have pieces of imported Samian pottery.[15]

Just inside the earthworks, at Lexden, are located the burial mounds of the rulers of Camulodunon, which contain large amounts of grave goods including imported Roman material from Europe;[5] the largest of these mounds is the Lexden tumulus.[16][17] The Lexden area around the mounds contains several Iron Age cremation burial groups, including one containing the "Mirror burial", with other burials located around the Camulodunon site.[5] Iron Age salt works (known as Red hills) have been found in large numbers around the Essex coast, including several large concentrations located in the salt marshes close to Camulodunon in the Colne Estuary, on the Roman River near Fingringhoe, in Alresford Creek, on Mersea Island, the Pyefleet Channel, the Blackwater River and around the Tendring Peninsula.[18] Two large groups existed at Peldon and Tolleshunt D'Arcy.[19] Camulodunon may have been an at the centre of the local trade in this important preservative.[18]

Addedomarus, a king of the Trinovantes tribe (originally centred at Braughing), is the first identifiable ruler of Camulodunon, known from his inscribed coins dating to around 25-10 BC. For a brief period around 10 BC Tasciovanus, a king of the Catuvellauni already issuing coins from Verlamion, also issued coins from Camulodunon, suggesting that the Trinovantes' capital had been conquered by the Catuvellauni, but he was soon forced to withdraw, perhaps as a result of Roman pressure – his later coins are no longer marked with the Latin REX (for king), but with the Brythonic RICON – and Addedomarus was restored. His son Dubnovellaunus succeeded him, but was soon supplanted by Tasciovanus' son Cunobelinus. Cunobelinus then succeeded his father at Verlamion, beginning the dominance of the Catuvellauni over the south-east.[20][21] Cunobelinus was friendly with Rome, marking his coins with the word REX and classical motifs rather than the traditional Gallo-Belgic designs. Archaeology shows an increase in imported luxury goods, probably through the Sheepen site port of Camulodunon, during his reign.[22] He was probably one of the British kings that Strabo says sent embassies to Augustus. Strabo reports Rome's lucrative trade with Britain; the island's exports included grain, gold, silver, iron, hides, slaves and hunting dogs.[23] Iron ingots, slave chains and storage vessels discovered at the Sheepen site appear to confirm this trade with the Empire.[5]

The Pre-Boudican Roman Town

The Claudian Invasion

| ||||||

The Catuvellauni king Cunobelinus, ruling from his capital at Camulodunon, had subjugated a large area of southern and eastern Britain,[2][3] and was called by the Roman historian Suetonius "King of the Britons".[5] Under his rule Camulodunon had replaced Verlamion as the most important settlement in pre-Roman Britain.[3] Around 40AD he had fallen out with his son Adminius (acting as proxy ruler of the Cantiaci tribe in his father’s name), who had fled to Rome for support.[5] There he was received by the Emperor Gaius, who may have attempted an invasion of Britain to put Adminius on his father’s throne.[24] After Cunobelinus’ death (circa 40AD) his sons took power, with Togodumnus the eldest ruling the Catuvellauni homeland around Verlamion, and Caratacus ruling from Camulodunon.[5] Together these brothers began expanding their influence over other British tribes, including the Atrebates of the south coast. Verica, king of the Atrebates, which had branches on both sides of the English Channel and had been friends of Rome since Caesar’s conquest,[25] appealed to the Emperor Claudius for aid. At the time of this appeal in 43AD the newly enthroned Emperor Claudius was in need of a military victory in order to secure his shaky position with the military, and saw this call for help as the perfect pretext.[26] Aulus Plautius led the four Roman legions across to Britain with Camulodunon being their main target,[2] defeating and killing Togodumnus near the Thames and then waiting for Claudius to cross the Channel. Claudius arrived with reinforcements, including artillery and elephants,[27] leading the attack on Camulodunon. Caratacus fled the storming of the town, taking refuge with the Ordovices and Silures tribes in Wales and becoming a Welsh folk hero for his resistance to Rome.[5] The Roman historian Suetonius and Claudius' triumphal arch state that after this battle the British kings who had been under Cunobelinus’ sons’ control surrendered without further bloodshed, Claudius accepting their submission in Camulodunon.[28]

Roman Fortress and Early Town

As the stronghold of a major tribe in the south-east, Camulodunum held strategic importance.[6] A Roman legionary fortress or castrum, the first permanent legionary fortress to be built in Britain,[5] was established within the confines of Camulodunon (which was latinised as Camulodunum) following the successful invasion in 43AD, and was home to the Twentieth Legion.[2] A smaller fort was built against the Iron Age earthworks close to the Gosbecks high-status farmstead, and was home to the Ala Primae Thracum (The First Wing of Thracians, a cavalry regiment) and the Cohors Primae Vangionum (The First Cohort of Vangiones, a mixed cavalry-infantry unit from Gaul).[29]

The legionary fortress was larger than a standard castrum, and included a large annexe on its north-east side.[5] It was protected by a large palisaded ditch and wall (Roman military Vallum and Fossa), along with new earthwork ditch and rampart defences, built to supplement the existing native defences.[3][30][31] One of these was around the Sheepen site, which became the main Roman port for the fortress and later for the town, with another military river port at Fingringhoe.[5] The fortress had two main metalled roads, a North-South via principalis and an East-West via praetoria, as well as a via sagularis around the inside of the defensive walls.[31] Along the roads leading out of the fortress settlements known as vici developed, home to native Britons who served the Roman garrison.[5] The interior of the fortress consisted of long barrack blocks able to hold groups of eighty soldiers, known as a Century, with a large room for a Centurian at one end of each block.[31] Larger buildings for military Tribunes have been excavated in the centre of the fort[31] The walls of the military buildings were built on mortared plinths called opus caementicium, with wooden and daub walls faced with keyed plaster.[31] Roman military equipment and weapons have been found from the fortress, including swords, armour and harness fittings.[3]

After the legion was withdrawn in c. 49 AD, the legionary defences were dismantled and the fortress converted into a town, with many of the barrack blocks converted into housing.[5][7] It’s official name became Colonia Victricensis, with discharged Roman soldiers making up the population; a bronze military diplomata (document formalising a soldier's retirement, citizen rights and land rights) for a legionary soldier called Saturninus has been found at the Sheepen site.[5] As a colonia (the only one in Britain at the time) its citizens held equal rights to Romans, and it was the principal city of Roman Britain.[5] Tacitus wrote that the town was "a strong colonia of ex-soldiers established on conquered territory, to provide a protection against rebels and a centre for instructing the provincials in the procedures of the law".[3] The Temple of Claudius, the largest classical style temple in Britain, was built there in the 50sAD and was dedicated to Emperor Claudius on his death in 54AD.[6][7] The podium, or foundation of the temple, was incoporated into the Norman castle, and represents "the earliest substantial stone building of Roman date visible in the country".[3] A monumental arch was built from tufa and Purbeck Marble at the western gate out of the town.[31] Tombs lined the roads out of the town, with several belonging to military veterans giving insights into the military units stationed in Britain during the post-Conquest period, such as:

- The famous tomb of the Thracian cavalryman Longinus Sdapeze,[32] depicting a Thracian horseman on horseback with full armour, in triumph over a cowering Briton. It reads:

- LONGINVS.SDAPEZE

- MATYCI.F.DVPLICARIVS.ALA.PRIMA.TRACVM.PAGO

- SARDICA.ANNO.XL.AEROR.XV

- HEREDES.EXS.TESTAM.F.C.

- H S E

- (Translated: Longinus Sdapeze, son of Matycus, Duplicarius of Ala Primae Thracum, from the country district of Sardica, who lived for forty years, with fifteen years paid service. His heirs set this up as stipulated in his will. He lies here.)[29]

- The tomb of the Centurion Marcus Favonius Facilis from Rome, depicting him in full military dress, is one of the finest examples,[3][5][32] and reads:

- M.FAVONI.M.F.POL.FACI

- LIS.C.LEG.XX.VERECVND

- VS.ET.NOVCIVS.LIB.POSVERVNT H S E

- (Translated: For Marcus Favonius Facilis, son of Marcus, of the Pollentian voting tribe, centurion of the Twentieth Legion, Verecundus and Noucius his freedmen have placed [this memorial]. He lies here.)[13]

- The tomb of an Auxialiary from Gaul:

- D M AR... RE... VAL... COH I VA... QVI M... EX AERE COLLATO

- (Translated: To the spirits of the departed and to Ar[...] Re[...] Val[...] of the First Cohort of Vangiones, who [...] former collector of taxes.)[29]

- The tomb of another experienced Centurion from Anatolia:

- ...LEG I (or II) ADIVTRICIS... ...AE BIS C ... ... BIS C LEG III AVG ... C LEG XX VAL VICTORIVNDVS NICAEA IN BITHYNIA MILITAVIT ANN ... VIXIT ANN ... ...

- (Translated: [...] of Legio Primae Adiutrix [...] twice centurion [...] twice centurion of Legio Tertiae Augusta [...] centurion of Legio Vicesimae Valeria, Victoriundus, from Nicaea in Bithynia, with [...] years military service who lived for [...] years [...])[13]

By 60-61 AD the population may have been as high as 30,000.[33]

Iceni Revolt

The city was the capital of the Roman province of Britannia, and its temple (the only classical-style temple in Britain) was the centre of the Imperial Cult in the province.[5] The Roman philosopher Seneca mentioned the temple when he mocked the province for its piety towards the Deified Claudius.[35] The colonia was also initially home to the provincial Procurator of Britain. Aside from the Roman population, the city and surrounding territorium was also home to a large native population. Examples of cooperation between the two groups include the Romano-British Stanway Burials mounds[5][36] and the warrior graves of native elites from the AD50s.[37][38] These graves represent members of the native aristocracy who have been Romanised.[19]

However tensions arose in 60/61AD when the Roman authorities used the death of Prasutagus as a pretext for seizing the Iceni client state from his widow Boudica. The Iceni rebels were joined by the Trinovantes around Colonia Victricensis, who held several grudges against the Roman population of the town. These included the seizure of land for the colonia’s veteran population, the use of labour to build the Temple of Claudius, and the sudden recall of loans given to the local elites by leading Romans (including Seneca and the Emperor), which had been needed to allow the locals to qualify for a position on the city council.[5][39] The Procurator Catus Decianus was especially despised.[2]

Tacitus recorded that certain ominous portents occurred in the town prior to the rebellion:

- "[...]the statue of Victory fell down, its back turned as though in retreat from the enemy. Women roused into frenzy chanted of approaching destruction, and declared that the cries of the barbarians had been heard in the council-chamber, that the theatre had re-echoed with shrieks, that a reflection of the colonia , overthrown, had been seen in the Thames estuary. The sea appeared blood-red, and spectres of human corpses were left behind as the tide went out".[3]

As the symbol of Roman rule in Britain the city was the first target of the rebels, with its Temple seen in British eyes as the "arx aeternae dominationis" ("stronghold of everlasting domination") according to Tacitus.[3] He wrote that it was undefended by fortifications when it was attacked[39] with a garrison of only 200 members of the procurator's guard.[6] He wrote of a last stand at the Temple of Claudius:

- "In the attack everything was broken down and burnt. The temple where the soldiers had congregated was besieged for two days and then sacked.".[3]

The rebels destroyed the city and slaughtered its population. Archaeologists have found layers of ash in the site of the city, suggesting that Boudica ordered her rebel army to burn the city to the ground.[40] A relief army consisting of the Legio IX Hispana led by Quintus Petillius Cerialis attempted to rescue the besieged citizens, but was destroyed outside of the town. After the Romans under governor Gaius Suetonius Paullinus finally defeated of the uprising, the Procurator of the province moved his seat to the newly established commercial settlement of Londinium (London).[41]

Boudican Destruction Layer

The destruction of the early town by the rebels has left a thick layer of ash, destroyed buildings and smashed pottery and glasswork across the town centre and at the Sheepen river port site outside the NW corner of the town. The destruction layer, also found at Verulamium (St Albans) and Londinium (London), is famous for the charred preservation of artefacts and furniture,[3] including a samian store, a glass store, beds and matresses, wall plaster, tessalated floors, a few human bones with wounds and even dates and plums.[30][31][42] During excavations in 2014 at Williams and Griffin on the High Street a collection of gold and silver jewellery was discovered buried in the floor of a Roman building destroyed during the revolt.[43] Known as the "Fenwick Treasure", it appears to have been buried just prior to the buildings destruction by a victim of the Boudican attack.[43] The layer is important to historians as it is one of the first archaeological contexts in Britain that can be given a definitive date, as well as to archaeologists as it provides a snapshot of artefacts from 60AD, allowing typologies of finds to be tied into a historical timeline, for example in Samian production.[44] The rubble from the destruction was landscaped during the rebuilding of the town that took place in the years after the revolt.[45]

Colonia Victricensis in the Second and Third Centuries

Following the destruction of the Colonia and Suetonius Paulinus’ crushing of the revolt the town was rebuilt on a larger scale and flourished,[13] growing larger in size than its pre-Boudican levels (to 108 acres/45 ha)[3] despite its loss of status to Londinium, reaching its peak in the Second and 3rd centuries.[5] The town's official name was Colonia Claudia Victricensis (City of Claudius’ Victory), but it was known colloquially by contemporaries (such as on the monument of Gnaeus Munatius Aurelius Bassus in Rome - see below) as Camulodunum or simply Colonia.[5] The colonia became a large industrial centre, and was the largest, and for a short time the only, place in the province of Britannia where samian ware was produced, along with glasswork and metalwork, and a coin mint.[5] Roman brick making and wine growing also took place in the area. Colonia Victricensis contained many large townhouses, with dozens of mosaics and tessellated pavements found, along with hypocausts and sophisticated waterpipes and drains.[5][46]

The colonia is mentioned by name several times by contemporaries, including in Pliny's Natural History, Ptolemy's Geography, Tacitus' Annales, The Antonine Itinerary and the Ravenna Cosmography.[13] The Second century AD tomb inscription for Gn. Munatius Bassus in Rome, which describes the name of the town and it's Roman citizenship, reads:

- GN.MVNATIVS.MF.PAL

- AVRELIVS.BASSVS

- PROCAVG

- PRAEF.FABR.PRAEF.COH.III

- SAGITTARIORVM.PRAEF.COH.ITERVM.II

- ASTVRVM.CENSITOR.CIVIVM

- ROMANORVM.COLONIAE.VICTRI

- CENSIS.QVAE.EST.IN.BRITTANNIA

- CAMALODVNI.CVRATOR

- VIAE.NOMENTANAE.PATRONVS.EIVSDEM

- MVNICIPI.FLAMEN.PERPETVS

- DVVM.VIR.ALI.POTESTATE

- AEDILIS.DICTATOR.IIII.

- (Translated: Gnaeus Munatius Aurelius Bassus, son of Marcus of the Palantine Tribe, Procurator of the Emperor, Prefect of the Armourers, Prefect of the Third Cohort of Archers, Prefect again of the Second Cohort of Asturians, Census Officer of the Roman Citizens of Colonia Victricensis, which is in Britain at Camulodunum, Overseer of the Nomentum Road, Patron again of the same municipality, Priest for life, Aedile with magisterial power, Dictator four times.)[5]

Status

The city was one of the few Roman settlements in Britain designated as a Colonia rather than a Municipia, meaning that in legal terms it was an extension of the city of Rome, not a provincial town. Its inhabitants therefore had Roman citizenship. Of the two provincial administrators the senatorial military governor was always located in areas of conflict,[47] whilst the civilian Procurator’s office had moved from Camulodunum to the new port of Londinium sometime around the Boudican Revolt.[5] However the Colonia did retain the Imperial cult centre and priesthood at the Temple of Claudius. The colonia was at the centre of a large territorium containing many villa sites, including an important cluster around the Colne estuary.[2]

Walls

Following the rebuilding of the town after 60/1AD new walls and a large defensive ditch were built around the colonia (the first town walls in Britain, predating other such walls in the province by at least 150 years[3]). They were completed by 80AD, twenty years after the revolt.[3][7] They were built with two external faces of alternating layers of tile and septaria mudstone containing a core of septaria boulders, with a 10 ft wide and 4 ft deep foundation trench, the whole structure taking up 45,000 cubic metres of stone, tile and mortar.[3][19][31] They were 2,800m long and 2.4m thick, and survive up to a height of over 6m in the 21st Century.[5] Later, in around 175-200AD a large earth bank was built up against the inner face of the walls.[3] The walls had between 12 and 24 towers and six large gates.[5] Balkerne Gate, in the centre of the Western section of the walls, was the main gate out of the town. It has a large fortified barbican that still stands as Britain’s largest Roman gateway, which incorporated the earlier monumental arch built before the Iceni rebellion and was flanked by two possible temples,[31] one of which may have contained the Venus statuette found during the 1973-76 excavations.[48] Skulls showing signs of decapitation were found in the town ditch in front of the gate, interpreted as executions on public display.[31] The North wall contained two gates, the modern North Gate and Duncan’s Gate, the East wall had the modern East Gate, and the Southern wall had the modern South Gate and Head Gate.[5] Drains were constructed in the wall to allow sewerage out of the colonia.[49]

Streets

The Cardo maximus, the main North-South street, ran between North Gate and Head Gate, whilst the Decumanus Maximus, the main East-West street, ran between Balkerne Gate and East Gate, and have their origins in the Legionary fortresses two main axial streets.[5] They were well paved, had drainage channels and were fronted with houses and shops.[50] Many included footways, a feature that is rare in other Roman British towns.[31] The rest of the colonia was gridded into around forty blocks known as insula, with paved streets and colonnaded paths between.[30][31] As well as a system of local roads leading to settlements around the colony, Camulodunum was linked to the rest of the Province by several major roads, including Stane Street, Camlet Way, Pye Road and the Via Devana.

Public Buildings

Within the town walls was located the Temple of Claudius in its large temple precinct with a monumental columned arcade.[51][52] Parts of the temple precinct wall are still visible to the NW of the present castle, jutting out from beneath the Norman bailey rampart.[3] The front of the precinct wall consisted of a large columned arcade screen extending the full width of the frontage.[5] At the centre of this arcade stood the entranceway to the temple precinct, which took the form of a tufa-faced monumental arch that at 8m wide was about 2m wider than the one at the Eastern entrance to the town, which had been incorporated into Balkerne Gate.[5] To the west of the temple on the modern Maidenburgh Street was a 3,000-seat capacity Roman theatre, which now has the Norman chapel of St Helena built into the corner of it,[3] currently open to public viewing.[3][30] Opposite the Temple, on the south side of the Decumanus Maximus, the remains of a possible Basilica have been identified.[5] At least seven Romano-Celtic temples have been identified at Camulodunum,[7] with the largest located at the Gosbecks area to the south of the town, built within the site of a former Iron-Age enclosure.[5] A large portico with an eastern entrance ran all the way around the outside of the site, with a solid outer wall, a row of columns down the centre of the portico and a second row of columns around the inner side.[5] In all there were about 260 columns placed 2m apart, and reaching a height of at least 5m.[5] The portico ran around the outside of a deep, Iron-Age enclosure ditch, which separated the portico from the central space in the middle of the site. This central space contained a large Romano-Celtic temple, which stood off-centre leading to suggestions that something else stood at the heart of the religious complex.[5] Next to the Gosbecks temple stood a second 5,000-seat theatre, Britain’s largest at 82m in diameter.[3][19] A group of four Romano-Celtic temples stood at the Sheepen industrial site, one of which was dedicated to Jupiter.[53] Temple I at the Sheepen site was found to be enclosed by a large, buttressed precinct wall during excavations in 1935 and 2014.[54] In 2005, the only known Roman circus in Britain was discovered on the southern outskirts of the colonia.[55] It is about 450 metres long, with eight starting-gates, and it was built in the early 2nd century AD.[56] It could accommodate at least 8,000 spectators and maybe up to as many as double that.[56] The structure’s gates are being opened to the public.[57] Several temples and religious monuments in and around the colonia have evidence for the deity honoured by them:

- A statue of Venus was found in the vicinity of the temple outside of the Balkerne Gate.[5]

- A statue of Mercury was found at the site of the Gosbecks temple.[7]

- The Temple at the Colchester Royal Grammar School has several plaques dedicated to Silvanus,[5] including:

- DEO SILVANO CALLIRIO D CINTVSMVS AERARIVS VSLM

- (Translated: To the god Silvanus Callirius, Decimus Cintusmus, coppersmith, willingly and deservedly fulfilled his vow.)[52]

- DEO SILVANO HERMES VSLM

- (Translated: To the god Silvanus, Hermes willingly and deservedly fulfilled his vow.)[52]

- The largest of the four temples at the Sheepen site has a plaque dedicated to Jupiter:

- P.ORANIVS

- FACILLIS.IOVI

- SIGILLUM.EX.TESTA

- (Translated: Publius Oranius Facilis gave a statue to Jove under the terms of his will)[5]

- An altar to the SW of the town dedicated to the Suleviae:

- MATRIBVS SVLEVIS SIMILIS ATTI F CI CANT VSLM

- (Translated: To the Sulevi mothers, Similis the son of Attius, of the Civitas Cantiacorum, willingly and deservedly fulfills his vow.)[13]

- A Bronze plaque dedicated sometime between 222 and 235AD by a Syrian to Mars and the Emperor Imperator Caesar Marcus Aurelius Severus, himself a Syrian:

- DEO MARTI MEDOCIO CAMPESIVM ET VICTORIE ALEXANDRI PII FELICIS AVGVSTI NOSI DONVM LOSSIO VEDA DE SVO POSVIT NEPOS VEPOGENI CALEDO

- (Translated: To the god of the battlefields Mars Medocius, and to the victory of [Imperator Caesar Marcus Aurelius Severus] Alexander Pius Felix Augustus, Lossius Veda the grandson of Vepogenus Caledos, placed [this] offering out of his own [funds].)[13]

- A monument, built by a local artisan Maronius, was dedicated to the "Numinibus Augusti" (Spirit of the Emperor) and Mercury:

- NVMINIB AVG ET MERCV DEO ANDESCOCI VOVCO IMILCO AESVRILINI LIBERTVS ARAM OPERE MARONIO D S D

- (Translated: To the Spirit of the Emperor and the God Mercury, Andescoci Vouco Imilco Aesurilini, freedman, [dedicates] this altar, the work of Maronius, donated out of his own [funds].)[13]

Marble from many of these public structures has been found, including Purbeck Marble and giallo antico (a rare yellow marble from Tunisia),[3] as well as statutes, inscriptions and plaques.[5] Several other public buildings have been postulated for which evidence is so far lacking, for example depictions on pottery, glasswork and wall plaster from the colonia of gladiators has been suggested as evidence that the town could have possessed an amphitheatre.[3][5]

Water Management

The town's streets and walls feature many brick built drains, including several large examples in Castle Park and near St Botolph's Priory.[3] As well as drains the colonia also possessed pipes for bringing pressurised water into the settlement. At the excavations at Balkerne Lane four lines of hollow wooden pipes, joined with iron collars were found bringing water from nearby springs, as well as evidence of a possible raised wooden acqueduct which may have been briefly in existence next to Balkerne Gate.[31] Further pipes have been discovered across the town.[58] The water would have been pressurised in reservoirs; it has been argued by archaeologist Philip Crummy that the pipes would have been fed by a castellum divisiorum, a water tower with multiple outlets, and that in order to get water to where the pipes at Balkerne Lane were found some form of aqueduct or water-lifting wheel would have been need to bring it from springs West of the town.[31] Within the town, a complicated system of chambers, water pipes and slots for possible water-wheels was found in Castle Park that were once described as a Mithraeum but that has now been reinterpreted as a reservoir system. A large overflow drain ran from the structure down to a culvert near Duncan's Gate where the excess water exited the town into the River Colne.[5] Timber framed wells have also been discovered, and there are at least nine springs located within the walls of Camulodunum.[31][59] Private baths have been found at some sites, but as yet no public baths have been positively identified.[31]

Houses

Many houses have been found in the colonia during archaeological excavations. Stone founded buildings largely replaced timber ones in the course of the second century, while average house size tended to increase in size up to a peak at around 250AD.[60] They have painted plaster walls and tiled roofs, many with tessellated mosaic floors, hypocaust systems, private baths and courtyards.[30][31] Latrine pits, with examples well over a metre deep, have been discovered next to some of the houses.[30] Large houses were also found in the extramural suburbs outside of the town walls, with the Middleborough House beneath the old Cattle Market being the largest, containing many rooms, mosaics and basements.[31] The Beryfield mosaic (of 180/200AD) from the SE corner of the colonia is the best preserved of the more than 50 mosaics found in the town.[3]

Cemeteries

In keeping with Roman burial customs the cemeteries for adults of the colonia in the First, Second and Third centuries are all located outside of the walls along the main roads out of the town,[59] with infants and neo-natals buried within the walls.[31] The cemeteries, some of which are walled, initially contained cremation burials, with ashes placed within jars and urns depicting human faces or glass vessels; these jars were sometimes buried in "boxes" made from ceramic tiles and hypocaust flue blocks to protect the vessel.[32][61] Some cremation pots have graffito on them, with PVERORVA ("remains of the boys") scratched on one,[61] as do some glass vessels, such as one found with CN.A.ING.A.V.M. scratched on it (presumably the initials of the interred ashes).[62] Later (post-c.260AD) burials are inhumations,[7] some in lead coffins decorated with patterns and images of scallop shells,[59] and some with wooden superstructures above and around them.[63] Examples of bustum burials (funerary pyre that is then covered with a mound) have been found, which are rare outside of Italy.[64] Elaborate grave goods accompanied some of the burials.[65] Many fragments of carved tombstones have been found in the cemeteries outside of the town,[5] with several being near complete such as the "Colchester Sphinx".[3] Some of the inscriptions on the tombs are almost fully intact, including:

- The tomb of a Roman Equites:

- ...OS... ... MACRI... ... VS EQ R VIX AN XX V FRONTINA CONIVNX ET FLOR COGITATVS ET FLOR FIDELIS FECERVNT

- (Translated: [...] Macri[nus] [Flor]us, a knight of Rome, who lived for twenty-five years, Frontina his wife, with Florus Cogitatus and Florus Fidelis, have made [this memorial].)[13]

- The tomb of a young man:

- D M IN HOC TVMVLO TEGVNTVR OSSA VENERABILIS IVVENIS ... CVNCTI MVCIANVM ... ERVNT SER ... ... VN ...

- (Translated: To the spirits of the departed, within this mound are being protected the bones of the honourable young man [...] Cunctius Muciana [...] they are overthrowing slavery [...])[13]

Other funerary monuments include the large tower-like ossuary containing the remains of cremated individuals and birds of prey, which was found at the junction between the road to London and the road to Gosbecks beneath the modern Colchester Royal Grammar School.[66]

Industry and Economy

Pottery Production

Camulodunum was a centre for pottery production, peaking at around 200AD,[60] and over 40 kilns have been in the town, including those found in the northern suburbs of the colonia around Middleborough[31] and a large group at Warren Fields and Oak Drive on the southern outskirts of the Sheepen site.[31] Many of the kilns are of the oval "Colchester type", whilst tile kilns have larger rectangular chambers.[31] Camulodunum produced many types of pottery, including decorated Samian pottery,[67] mortaria, buff wares,[68] single-handled ring-necked flagons,[61] and, until c.250AD, colour-coated wares.[61] In the late First century AD amphorae, called "Camulodunum Carrots" for their shape and colour, were made in the colonia, and are found in thin numbers across Britain.[61] The Samian industry, copying the East Gaullish style, was active for a time in Camulodunum from 160 to about 200AD,[44] with the names of several individual Samian potters identified as working in the colonia.[61] Over 400 fragments of Samian moulds for producing the decorated pottery have been uncovered in the town,[44] including 37 complete examples.[61] A well preserved Samian kiln was excavated by archaeologist M.R. Hull near Middleborough, just outside of North Gate. It was 8 ft wide, with a 5m flue under a large circular kiln chamber, and had a complex system of ceramic pipes and tubes for regulating the oxidisation of the pottery to produce its distinctive red colour.[44] Several of the potters operating in Camulodunum in the First, Second and Third centuries are identified as immigrants from the Rhine Valley and East Gaul, including the Samian potter Minuso from Trier who also operated in other British towns,[44] Miccio,[5] the mortaria potter G. Attius Marinus and several men called Sextus Valerius.[2][44] Pottery made in Camulodunum can be found across the East of England, and as far away as Eboracum.[69] One of the most famous examples of locally made pottery is the "Colchester Vase" (c. 200AD), which depicts combat between gladiators called Memnon and Valentinus.[3]

Other Activities

As well as pottery, ceramics produced in Camulodunum also include a large tile industry, oil lamps and figurines.[61] The colonia was also a major centre of glass production,[4][70] and glass moulds (including a complete example) have been discovered in the town.[62] Glass was produced throughout the Roman period of Camulodunum, including in the late Fourth century,[62] and glass-making waste was discovered at Culver Street from the mid-First century.[30] Bone carving for ornamentation,[59] metal working and jewellery making[5] were also practiced, and a coin mint[2] operated in the colonia. Archaeological excavations suggest that the period between 150 and 250AD saw the largest number of active workshops in the colonia.[60] The town was at the centre of a largely rural economy,[7] with archaeological evidence of agricultural buildings in the colonia including the large buttressed tower granary found in the Southern part of the town, in use for much of the Second century, with a nearby corn-drying oven.[30] Many ovens have been located in excavations around the town.[5][30] A system of watermills appears to have operated along Salary Brook near Ardleigh to the north of the settlement,[71] and other watermills may have operated on the Colne at the modern site of Middle Mill in Castle Park.[5] Oysters from the Colne Estuary and Mersea Island have been an important food source throughout much of Colchester's history, and large dumps (some 0.5m thick) of oyster shells have been found at Balkerne Hill from the Roman period,[5][31] along with mussels, whelks, cockles, carpet shells, winkle and scallop; fish imported from the River Colne and coast are represented by herring, plaice, flounder, eel, smelt, cod, haddock, gurnard, mullet, dragonet, dab, and sole.[30] As well as the Sheepen river port, Roman roads lead to Mistley on the Essex bank of the River Stour and to a cluster of Roman-era buildings at West Mersea, both of which may also have possessed ports for the colonia.[5] Imports of dates, wine (including Falernian wine), olive oil, jet, marble and other goods from across the Roman Empire have been found in Colchester,[5] including a locally made amphora with an inscription suggesting that it held North African palm-tree fruit products.[61] The trade in salt from local Red Hills also appears to have continued on from the Iron Age in the Roman period, but with more sophisticated evaporation kilns.[18] Small numbers of tiles were imported from Eccles in Kent by Roman settlements in South-East Britain, including Camulodunum, for a brief time in the First Century, as was Kentish Ragstone for building.[30]

Late Roman Town

The late Third century and Fourth centuries saw a series of crises in the Empire, including the breakaway Gallic Empire (of which Britain was a part), and raids by Saxon pirates, both of which lead to the creation of the Saxon Shore forts along the East coast of Britain.[7] The fort at Othona overlooking the confluence of the Blackwater and Colne estuaries, and two more at the mouth of the river into the colonia were built to protect the town.[5][19] Balkerne Gate and Duncan’s Gate were both blocked up in this period, with the later showing signs of being attacked.[5] The extramural suburbs outside of Balkerne Gate had gone by 300AD[7] and were replaced by cultivation beds.[72] The re-cutting of the town ditch in front of the newly blocked Balkerne Gate in 275-300AD involved destroying the water pipes which entered the colonia through the gate. However a small portal in the gateway may have been opened up later.[72] The town ditch began to silt up from c.400AD onwards.[72]

As with many towns in the Empire, the colonia shrunk in size in the 4th Century AD but continued to function as an important town.[60] Although houses tended to shrink in size, with 75% of the large townhouses being replaced by smaller buildings by c.350AD,[60] in the period 275 to 325 a weak "building boom" (the "Constantinian renaissance") occurred in the town, with new houses being built and old ones reshaped.[60] Many of the towns mosaics date from this period, including the famous Lion Walk mosaic.[3] Late Roman robber trenches have been found at some sites for removing and salvaging tessalated floors and tiles for reuse in later houses.[30][31] The pottery industry in the town had declined significantly by 300AD,[60] but the Fourth century did see an increase in the bone-working industry for making furniture and jewellery,[30] and evidence of blown glass making has also been found.[30] Large areas of the Southern part of the town were given over to agriculture.[30]

Despite the scaling down of private buildings an increase in the size and grandeur of public buildings occurs in the period 275-400AD.[60] The Temple of Claudius and its associated temenos buildings were reconstructed in the early-Fourth century, along with the possible forum-basilica building to the south of it.[73] The Temple appears to have had a large apsidal hall built across the front of the podium steps, with numismatic dating evidence taking the date of the building up to at least 395AD.[73] A large hall at the Culver Street site, dated 275-325 to 400+AD, may have been a large centralised storage barn for taxes paid in kind with grain.[30][60]

Although the Gosbecks Theatre had been demolished by the Third Century, the theatre at Maidenburgh Street may still have been in use throughout the Fourth Century.[74] The sunken chambers of the water reservoir system found in Castle Park appear to have become blocked up with debris and dumped rubbish in the Fourth Century and had gone out of use.[75][76] The Roman chariot circus was also demolished during the late Fourth century.[77] Increases in the number of clipped coins from the Fourth Century have been interpreted as a breakdown in the Roman monetary economy,[5] with most new Bronze coins ceasing to be introduced in the town c.395AD and silver coins in 402AD (however these coins may have remained in circulation long after being minted).[60] For example, the coin sequence at the Butt Road church goes up to around 425AD, 14 years after Roman rule ended in the province.[60]

Late Roman military equipment has been discovered in the town,[78] including an official cingulum militare belt buckle made in Pannonia for Roman frontier units.[78] Alongside Roman military equipment Fourth and early Fifth Century Germanic weaponry has been found alongside Germanic domestic objects in the Late Roman town, which has been interpreted by archaeologist Philip Crummy as perhaps representing Saxon foederati mercenaries living and settling in the town during this period, several decades before the Saxon migrations of the mid to late Fifth Century.[78]

Christianity in the Late Roman Town

During this period the late Roman church at Butt Road[7] just outside the town walls was built with its associated cemetery containing over 650 graves (some containing fragments of Chinese silk), and may be one of the earliest churches in Britain.[5][59] A strong numismatic chronology has been obtained from the over 500 coins found at the site, and puts its date from 320AD to c.425AD.[72] Five of the extramural pagan Romano-British Temples were abandoned in c.300AD, whilst Temple II at Sheepen was rebuilt in 350AD and continued in existence until c.375AD.[75][76] Temple X outside of the Balkerne Gate had its ambulatory demolished in 325-50AD leaving just its Cella, perhaps repurposed as a Christian temple.[31] A nearby shrine may also have survived into the late Fourth century.[31] Several other possible churches or Christian buildings have been postulated, such as Building 127 at Culver Street and possible Roman remains beneath St Helena’s Chapel, St Nicholas Church and Roman "vaults" beneath St Botolph's Priory which might be a late-Roman Martyrium, although over interpretations include a bath-house.[76] The Temple of Claudius, which underwent large-scale structural additions in the Fourth century, may also have been repurposed as a Christian church, as a Chi Rho symbol carved on a piece of Roman pottery found in the vicinity of the temenos.[5] Further Roman Christian objects found in the town include a candlestick from Balkerne Lane inscribed with an Iota Chi symbol and a bronze spoon with AETERNVS VITA written on it.[59][79] Three British Bishops attended the Council of Arles in 314AD, one from London, one from York and a third from a place whose first word is Colonia but whose second word is too corrupted to make out with any certainty, but has been interpreted as something like Camulodensium (although Lincoln and Gloucester are other possible candidates).[59][79]

Sub-Roman Period

The formal collapse of Roman administration in the province occurred in the years 409-411AD. Activity in the Fifth century continued in Camulodunum at a much reduced level,[60] with evidence of at the Butt Road site showing that it briefly carrying on into the early fifth century.[59] Several burials within the towns walls have been dated to the Fifth century. These include two burials discovered at East Hill House in 1983, which have been surgically decapitated (in a fashion found in both Pre-Roman and some early pagan-Saxon burial practices),[5][7] and other burials cut into the Fourth century barn at Culver Street.[5] A skeleton of a young woman found stretched out on a Roman mosaic floor at Beryfield, within the SE corner of the walled town, was initially interpreted as a victim of a Saxon attack on the Sub-Roman town; however, it is now believed that the burial is a post-Roman grave cut down to the hard floor surface (the name Beryfield means Burial field, a reference to the Medieval graveyards in the area).[5] Burials of men armed with Germanic weaponry have also been found outside of the town walls, and might be the graves of Saxon foederati or Saxon settlers.[80] Post-Roman/early Saxon burials from the 5th, 6th and 7th centuries, some buried with weapons, have been found outside of the walls in the areas of former Roman cemeteries, suggesting a continuity of practice.[5] A study by archaeologist Henry Laver concluded that all of the Roman cemeteries around Colchester contain later burials dating to the early Saxon period.[78] As well as burials, coin hoards from the late Fourth and early Fifth centuries have been found, including a hoard minted in the reign of Constantine III (reigned 407-411AD) from Artillery Folly, that are heavily clipped; this clipping must have occurred in the years after they were minted and so would have happened in the 400s AD.[5][7] Scattered structures have also been excavated by archaeologists, such as a mid-Fifth century dwelling at Lion Walk,[31] as well as fifth century loam weights and cruciform-broaches found across the town.[5] At the Culver Street site a thin layer of early Saxon pottery was discovered along with two dwellings.[30] Other circumstantial evidence of activity includes large post-Roman rubbish dumps, which suggest nearby occupation.[60] Excavations at Guildford Road Estate have uncovered a Germanic-style brooch, dated to around the 420s AD, associated with a group of beads from a necklace, also dated to sometime between 400 and 440AD.[78] The presence of Late Roman and Germanic military and domestic finds within the Late Roman and Pre-Saxon Early-Fifth Century town has been interpreted by archaeologist Philip Crummy as either the result of Saxon foederati and their families living within Camulodunum, and/or cultural influences from the continent on the local population.[78] The existence of a post-Roman entity centred on the town, sometimes linked to the legend of Camelot, has been argued[81][10] and was first proposed by archaeologist Mortimer Wheeler.

Roman Legacy in Saxon and Early Medieval Colchester

Later dwellings at Culver Street and artefacts from the 7th and Eighth century are seen as evidence that the shell of the Roman town was still in use into the Saxon period.[5][30] The History of the Britons traditionally ascribed to Nennius includes a list of the 28 cities of Britain, including a Cair Colun[82] that has been thought to indicate Colchester.[83][84] Archaeology aside, Colchester first explicitly re-enters the written historical record again in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle for 917AD, the year it was retaken from the Danes by a Saxon army led by King Edward the Elder, who "restored" the borough to English rule.[5] The walls of the colonia have been retained,[78] and many of the Medieval and Saxon buildings in Colchester, including the Castle, St Botolph's Priory, St John's Abbey, Greyfriars, Holy Trinity church and many of the Norman "stone houses" were built from the vast amounts of Roman debris left over in the town.[5][85] Over 25,000 cubic metres of reused Roman tile and brick was used for the Castle alone.[5] The quarrying of Roman rubble for building material reached a peak in the 12th and 13th Centuries.[78]

Several structures from the Saxon and Medieval period incorporated Roman structural remains within their walls and outlines.[78] The Temple of Claudius was a standing ruin until the Normans cleared the superstructure to incorporate the podium into Colchester Castle in the 11th Century.[5][78] In 2014 the discovery of marble pillars belonging to the Monumental Facade of the Temple precinct was made behind the High Street, with evidence suggesting that they were still standing until the Castle-builders knocked them over to make way for the Castle Bailey.[86] The Normans referred to the Temple as King Coel's Palace and to the barbican of Balkerne Gate as Colkyng's Castle, reflecting a myth that continued into the Medieval period, and was recorded in the Colchester Chronicle (written in the 13th or early 14th century at St John's Abbey), that the Roman town was founded by a warlord called Coel. According to the Medieval legend,[5] which garbles folk-tales and pseudo-historical events together, he was supposedly the father of St Helena, who was married off to Constantius in a bid to get the latter to lift his two-year siege of the town. Their son, Constantine the Great was then supposedly born in the town. St Helena is today the patron saint of Colchester, and the town's coat of arms depict the True Cross and crowns of the Three Kings that she is supposed to have found in Jerusalem.[7] Other examples of Roman remains used in later buildings include several Medieval cellars on the High Street,[78] St Nicholas Church (demolished in the 1950s), which was built on a Roman building and originally incorporated the remains of standing Roman walls,[78] and St Helens Chapel, which was built into the corner of the Roman theatre in the town.[5][78] A study in the late 1970s by Colchester Archaeological Trust discovered that many of the Medieval property boundaries within Colchester's town centre followed the lines of Roman street frontages and the walls of Roman buildings.[78] This was especially prominent along the High Street, where the Medieval street "frontage of the High Street between St Runwald's Church and Maidenburgh Street has fossilized the imprint of the Roman town underneath...".[78] St Runwald's Church (demolished in the 1800s) formerly stood in the centre of the High Street market just east of the current Town Hall, and was built into the corner of a junction between two Roman streets.[78] The study concluded that Roman building ruins and old street remains were in some cases used as a template for later property divisions.[78]

The name of the town and the River Colne are also a legacy of the Romans. "Colchester" (first appearing in written form in the 10th Century as Colencaester and Colneceastre) is a Saxon name derived from the Latin words Colonia and Castra,[5] with the River Colne also taking its name from Colonia.[5]

See also

- History of Colchester

- Roman Britain

- Oldest town in Britain

- Temple of Claudius, Colchester

- Trinovantes

- Catuvellauni

- Cunobeline

- Caratacus

- Addedomarus

- Camelot

References

- ↑ "Camulodunum". Collins Dictionary. n.d. Retrieved 2014-09-26.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 Todd, Malcolm. (1981) Roman Britain; 55BC - 400AD. Published by Fontana Paperbacks (ISBN 0 00 633756 2)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.9 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 3.18 3.19 3.20 3.21 3.22 3.23 3.24 3.25 3.26 3.27 3.28 Wilson, Roger J.A. (2002) A Guide to the Roman Remains in Britain (Fourth Edition). Published by Constable. (ISBN 1-84119-318-6)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 McWhirr, Alan (1988) Roman Crafts and Industries. Published by Shire Publications LTD. (ISBN 0 85263 594 X)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 5.9 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.15 5.16 5.17 5.18 5.19 5.20 5.21 5.22 5.23 5.24 5.25 5.26 5.27 5.28 5.29 5.30 5.31 5.32 5.33 5.34 5.35 5.36 5.37 5.38 5.39 5.40 5.41 5.42 5.43 5.44 5.45 5.46 5.47 5.48 5.49 5.50 5.51 5.52 5.53 5.54 5.55 5.56 5.57 5.58 5.59 5.60 5.61 5.62 5.63 5.64 5.65 5.66 5.67 5.68 5.69 5.70 5.71 5.72 5.73 5.74 5.75 5.76 5.77 5.78 5.79 5.80 5.81 5.82 Crummy, Philip (1997) City of Victory; the story of Colchester - Britain's first Roman town. Published by Colchester Archaeological Trust (ISBN 1 897719 04 3)

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Mike Ibeji. "Roman Colchester: Britain's First City". BBC Online. Retrieved 2008-05-20.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 7.9 7.10 7.11 7.12 7.13 7.14 "Iron-Age and Roman Colchester", A History of the County of Essex: Volume 9: The Borough of Colchester (1994): 2-18, Janet Cooper, C R Elrington (Editors), A P Baggs, Beryl Board, Philip Crummy, Claude Dove, Shirley Durgan, N R Goose, R B Pugh, Pamela Studd, C C Thornton.. British History Online. Web. 01 June 2014

- ↑ Hull, M.R. (1958). Roman Colchester. The Society of Antiquaries of London

- ↑ McCloy, A.; Midgley, A. (2008). Discovering Roman Britain. New Holland. p. 60. ISBN 9781847731289. Retrieved 2014-10-25.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 http://www.camulos.com/arthur/official.htm retrieved 04/11/2014

- ↑ http://www.thecolchesterarchaeologist.co.uk/?p=967 retrieved 25/07/2014

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Denney, Patrick (2004) Colchester. Published by Tempus Publishing (ISBN 978-0-7524-3214-4)

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 13.7 13.8 13.9 http://www.roman-britain.org/places/camulodunum.htm retrieved 21/07/2014

- ↑ Sealy, P.R. (1985) Amphoras from the 1970 excavations of Colchester Sheepen. Oxford, British Archaeological Report 142

- ↑ Begley, Vimala and Daniel de Puma, Richard (eds.) (1991) Rome and India. The Ancient Sea Trade. Published by The University of Wisconsin Press (ISBN 0-299-12640-4)

- ↑ http://www.pastscape.org.uk/hob.aspx?hob_id=384037&sort=4&search=all&criteria=Lexden Tumulus&rational=q&recordsperpage=10 retrieved 22/07/2014

- ↑ http://unlockingessex.essexcc.gov.uk/uep/custom_pages/monument_detail.asp?content_page_id=89&monument_id=34083&content_parents=48 retrieved 22/07/2014

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Fawn, A.J.; Evans, K.A.; McMaster, I.;Davies, G.M.R. (1990) The Red Hills of Essex. Published by Colchester Archaeological Group. (ISBN 0 9503905 1 8)

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 Strachan, David (1998) Essex from the Air, Archaeology and history from aerial photographs. Published by Essex County Council (ISBN 1 85281 165 X)

- ↑ John Creighton (2000), Coins and power in Late Iron Age Britain, Cambridge University Press

- ↑ Philip de Jersey (1996), Celtic Coinage in Britain, Shire Archaeology

- ↑ Keith Branigan (1987), The Catuvellauni, Alan Sutton Publishing Ltd, pp. 10-11

- ↑ Strabo, Geography 4.5

- ↑ Suetonius (1989) The Twelve Caesars. Published by Penguin Classics. (ISBN 0-14-044072-0)

- ↑ Caesar (1982) The Conquest of Gaul. Published by Penguin Classics. (ISBN 0-14-044433-5)

- ↑ Scarre, Chris (1997) Chronicle of the Roman Emperors. The Reign-by-Reign Record of the Rulers of Imperial Rome. Published by Thames and Hudson. (ISBN 0-500-05077-5)

- ↑ Cassius Dio, Roman History 60.19-22

- ↑ Suetonius, Claudius 17; Arch of Claudius

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 http://www.roman-britain.org/places/stanway.htm retrieved 29/07/2014

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 30.4 30.5 30.6 30.7 30.8 30.9 30.10 30.11 30.12 30.13 30.14 30.15 30.16 30.17 Crummy, Philip (1992) Colchester Archaeological Report 6: Excavations at Culver Street, the Gilberd School, and other sites in Colchester 1971-85. Published by Colchester Archaeological Trust (ISBN 0-9503727-9-X)

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 31.4 31.5 31.6 31.7 31.8 31.9 31.10 31.11 31.12 31.13 31.14 31.15 31.16 31.17 31.18 31.19 31.20 31.21 31.22 31.23 31.24 31.25 31.26 Crummy, Philip (1984) Colchester Archaeological Report 3: Excavations at Lion Walk, Balkerne Lane, and Middleborough, Colchester, Essex. Published by Colchester Archaeological Trust (ISBN 0-9503727-4-9)

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 Toynbee, J.M.C. (1996) Death and Burial in the Roman World. Published by Thames and Hudson. (ISBN 0-8018-5507-1)

- ↑ Norwich, J.J. (2011). A History of England in 100 Places: From Stonehenge to the Gherkin. Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 9781848546080. Retrieved 2014-10-25.

- ↑ "Head of the Emperor Claudius". British Museum.

- ↑ Petronius – The Satyricon/Seneca – The Apocolocyntosis (1986) Published by Penguin Classics. (ISBN 0-14-044489-0)

- ↑ http://www.camulos.com/gosbecks.htm retrieved 21/07/2014

- ↑ http://www.gazette-news.co.uk/news/10677948._/ retrieved 22/07/2014

- ↑ http://www.archaeology.org/news/1309-130918-england-warrior-catuvellauni-spears retrieved 22/07/2014

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Tacitus (1876), XIV:31.

- ↑ http://www.thecolchesterarchaeologist.co.uk/?p=13560 retrieved 21/07/2014

- ↑ Graham Webster, Boudica: the British Revolt against Rome AD 60, 1978, pp. 89-90

- ↑ http://www.thecolchesterarchaeologist.co.uk/?p=13385 retrieved 24/07/2014

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 http://www.thecolchesterarchaeologist.co.uk/?p=14844 retrieved 04/09/2014

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 44.3 44.4 44.5 Bédoyère, Guy de la (1988) Samian Ware in Britain. Published by Shire Publications LTD. (ISBN 0 85263 930 9)

- ↑ http://www.thecolchesterarchaeologist.co.uk/?p=13568 retrieved 22/07/2014

- ↑ http://www.thecolchesterarchaeologist.co.uk/?p=13656 retrieved 21/07/2014

- ↑ Tacitus (1986) The Agricola and the Germania. Published by Penguin Classics (ISBN 0-14-044241-3)

- ↑ Crummy, Nina (1983) Colchester Archaeological Reports 2: The Roman small finds from Colchester 1971-9. Published by Colchester Archaeology Trust. (ISBN 0-9503727-3-0)

- ↑ http://www.camulos.com/virtual/townwall2.htm retrieved 21/07/2014

- ↑ http://www.thecolchesterarchaeologist.co.uk/?p=13656 retrieved 22/07/2014

- ↑ "Colchester: grand Roman arcade on a monumental scale | The Colchester Archaeologist". thecolchesterarchaeologist.co.uk. Retrieved 2014-10-25.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 http://www.roman-britain.org/places/colchester_temples.htm retrieved 20/07/2014

- ↑ http://www.thecolchesterarchaeologist.co.uk/?p=15908 retrieved 30/10/2014

- ↑ http://www.thecolchesterarchaeologist.co.uk/?p=16086 retrieved 07/11/2014

- ↑ http://www.thecolchesterarchaeologist.co.uk/?p=7882 retrieved 21/07/2014

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 "Circus Maximus games | The Colchester Archaeologist". thecolchesterarchaeologist.co.uk. Retrieved 2014-10-25.

- ↑ http://www.thecolchesterarchaeologist.co.uk/?p=13470 retrieved 21/07/2014

- ↑ http://www.thecolchesterarchaeologist.co.uk/?p=14116 retrieved 05/08/2014

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 59.2 59.3 59.4 59.5 59.6 59.7 Crummy, Nina; Crummy, Philip; and Crossan, Carl (1993) Colchester Archaeological Report 9: Excavations of Roman and later cemeteries, churches and monastic sites in Colchester, 1971-88. Published by Colchester Archaeological Trust (ISBN 1-897719-01-9)

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 60.2 60.3 60.4 60.5 60.6 60.7 60.8 60.9 60.10 60.11 60.12 Faulkner, Neil. (1994) Late Roman Colchester, In Oxford Journal of Archaeology 13(1)

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 61.2 61.3 61.4 61.5 61.6 61.7 61.8 Bédoyère, Guy de la (2000) Roman Pottery in Britain. Published by Shire Publishing LTD (ISBN 0 7478 0469 9)

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 62.2 Allen, Denise (1998) Roman Glass in Britain. Published by Shire Archaeology LTD. (ISBN 0-7478-0373-0)

- ↑ http://www.archaeology.co.uk/articles/news/remarkable-ringfenced-burials-from-roman-colchester.htm retrieved 22/07/14

- ↑ http://www.thecolchesterarchaeologist.co.uk/?p=3304 retrieved 22/07/14

- ↑ http://www.thecolchesterarchaeologist.co.uk/?p=5392 retrieved 22/07/14

- ↑ http://www.thecolchesterarchaeologist.co.uk/?p=2977 retrieved 22/07/14

- ↑ http://www.thecolchesterarchaeologist.co.uk/?p=13052 retrieved 22/07/2014

- ↑ Swan, Vivien G. (1988) Pottery in Roman Britain. Published by Shire Publishing LTD (ISBN 0 85263 912 0)

- ↑ Monaghan, Jason (1997) Roman Pottery from York. Published by York Archaeological Trust (ISBN 1 872414 83 4)

- ↑ http://www.cat.essex.ac.uk/reports/CAR-report-0008 Retrieved 22/07/14

- ↑ Spain, R. J. (1984) ‘Romano-British watermills’, Archaeologia Cantiana, 100, 101-28.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 72.2 72.3 Crummy, Philip (1987) The Coins as Dating Evidence. In Crummy, N. (ed.) Colchester Archaeological Report 4: The Coins from Excavations in Colchester 1971-9. Published by Colchester Archaeological Trust

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 Drury, P.J, (1984) The Temple of Claudius Reconsidered. Britannia XV, 7-50

- ↑ Crummy, Philip (1982) The Roman Theatre at Colchester. "Britannia XIII", 299-302

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 Hull, M.R. 1958 Roman Colchester. Oxford Society of Antiquities

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 76.2 Crummy, Philip (1980). The Temples of Roman Colchester. In Rodwell, W (ed.) Temples, Churches and Religion: Recent Research in Roman Britain. (Oxford, British Archaeological Report 77(i))

- ↑ http://www.thecolchesterarchaeologist.co.uk/?p=16088 retrieved 08/11/2014

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 78.2 78.3 78.4 78.5 78.6 78.7 78.8 78.9 78.10 78.11 78.12 78.13 78.14 78.15 78.16 Crummy, Philip (1981). Colchester Archaeological Report 1/CBA Research Report 39: Aspects of Anglo-Saxon and Norman Colchester. Published by Colchester Archaeological Trust and the Council for British Archaeology. (ISBN 0 90678006 3)

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 Toynbee, JMC (1953)'Christianity in Roman Britain' in Journal of Brit. Arch. Ass. 16 (3rd Series)

- ↑ http://www.thecolchesterarchaeologist.co.uk/?p=1154 retrieved 09/09/2014

- ↑ "King Arthur of the Britons and Camelot". camulos.com. Retrieved 2014-10-25.

- ↑ Nennius (attrib.). Theodor Mommsen (ed.). Historia Brittonum, VI. Composed after AD 830. (Latin) Hosted at Latin Wikisource.

- ↑ Ford, David Nash. "The 28 Cities of Britain" at Britannia. 2000.

- ↑ Newman, John Henry & al. Lives of the English Saints: St. German, Bishop of Auxerre, Ch. X: "Britain in 429, A. D.", p. 92. James Toovey (London), 1844.

- ↑ Ashdown-Hill, John (2009) Mediaeval Colchester's Lost Landmarks. Published by The Breedon Books Publishing Company Limited. (ISBN 978-1-85983-686-6)

- ↑ http://www.thecolchesterarchaeologist.co.uk/?p=13902 retrieved 26/07/2014

Bibliography

- Tacitus; Alfred John Church and William Jackson Brodribb (translators) (1876). The Annales.

External links

- Colchester Archaeological Trust home page

- Info on Roman Colchester

- History of Roman Colchester

- Colchester and Ipswich Museums Home Page

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Camulodunum. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||