Campo del Cielo

| Campo del Cielo | |

|---|---|

|

Campo del Cielo iron meteorite with natural hole, 576 grams | |

| Type | Iron |

| Structural classification | Octahedrite |

| Group | IAB |

| Composition | 92.9% Fe, 6.7% Ni, 0.4% Co |

| Country | Argentina |

| Region | Chaco Province and Santiago del Estero Province |

| Coordinates | 27°38′S 61°42′W / 27.633°S 61.700°WCoordinates: 27°38′S 61°42′W / 27.633°S 61.700°W |

| Observed fall | No |

| Fall date | 4,000–5,000 years ago |

| Found date | <1576 |

| TKW | >100 tonnes |

| Strewn field | Yes |

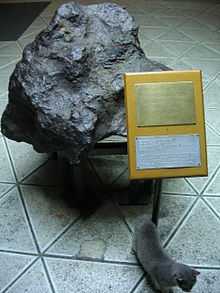

The Campo del Cielo refers to a group of iron meteorites or to the area where they were found situated on the border between the provinces of Chaco and Santiago del Estero, 1,000 kilometers (620 mi) northwest of Buenos Aires, Argentina. The crater field covers an area of 3×20 kilometers and contains at least 26 craters, the largest being 115×91 meters. The craters' age is estimated as 4,000–5,000 years. The craters, containing iron masses, were reported in 1576, but were already well known to the aboriginal inhabitants of the area. The craters and the area around contain numerous fragments of an iron meteorite. The total weight of the pieces so far recovered exceeds 100 tonnes, making the meteorite the heaviest one ever recovered on Earth. The largest fragment, consisting of 37 tonnes, is the second heaviest single-piece meteorite recovered on Earth, after the Hoba meteorite.[1]

History

In 1576, the governor of a province in Northern Argentina commissioned the military to search for a huge mass of iron, which he had heard that Natives used for their weapons. The Natives claimed that the mass had fallen from the sky in a place they called Piguem Nonralta which the Spanish translated as Campo del Cielo ("Field of Heaven"). The expedition found a large mass of metal protruding out of the soil. They assumed it was an iron mine and brought back a few samples, which were described as being of unusual purity. The governor documented the expedition and deposited the report in the Archivo General de Indias in Seville, but it was quickly forgotten and later reports on that area merely repeated the Native legends. Following the legends, in 1774 don Bartolome Francisco de Maguna rediscovered the iron mass which he called el Meson de Fierro ("the Table of Iron"). Maguna thought the mass was the tip of an iron vein. The next expedition, led by Rubin de Celis in 1783, used explosives to clear the ground around the mass and found that it was probably a single stone. Celis estimated its mass as 15 tonnes and abandoned it as worthless. He himself did not believe that the stone had fallen from the sky and assumed that it had formed by a volcanic eruption. However, he sent the samples to the Royal Society of London and published his report in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society.[2] Those samples were later analyzed and found to contain 90% iron and 10% nickel and assigned to a meteoritic origin.[3]

Later, many iron pieces were found in the area weighing from a few milligrams to 34 tonnes. A mass of about 1 tonne known as Otumpa was located in 1803. A 634 kilograms (1,398 lb) portion of this mass was taken to Buenos Aires in 1813 and later donated to the British Museum. Other large fragments are summarized in the table below. The mass called el Taco was originally 3,070 kilograms (6,770 lb), but the largest remaining fragment weighs 1,998 kilograms (4,405 lb).[4]

The largest mass of 37 tonnes was located in 1969 at a depth of 5 m using a metal detector.[3] This stone, named El Chaco, is the second heaviest single-piece meteorite after the Hoba meteorite (Namibia) which weighs 60 tonnes. However, the total mass of the Campo del Cielo fragments found so far exceeds 60 tonnes, making it the heaviest meteorite ever recovered on Earth.[5]

In 1990 a local Argentinean highway police officer foiled a plot by Robert Haag to steal El Chaco. The stone had already been moved out of the country, but was returned to Campo del Cielo and is now protected by a provincial law.[6]

The meteorite impact, age and composition

A crater field of at least 26 craters was found in the area, with the largest being 115×91 meters. The field covered an area of 3×19 kilometers with an associated strewn area of smaller meteorites extending farther by about 60 kilometres (37 mi). At least two of the craters contained thousands of small iron pieces. Such an unusual distribution suggests that a large body entered the Earth's atmosphere and broke into pieces which fell to the ground. The size of the main body is estimated as larger than 4 meters in diameter. The fragments contain an unusually high density of inclusions for an iron meteorite, which might have facilitated the disintegration of the original meteorite. Samples of charred wood were taken from beneath the meteorite fragments and analyzed for carbon-14 composition. The results indicate the date of the fall to be around 4,200–4,700 years ago, or 2,200–2,700 years BC.[3][7]

The average composition of the Campo del Cielo meteorites is 6.67% Ni, 0.43% Co, 0.25% P, 87 ppm Ga, 407 ppm Ge, and 3.6 ppm Ir, with the rest being iron.[3][8]

| Mass (tonnes) | Name | Year of discovery |

|---|---|---|

| >15 | el Meson de Fierro or Otumpa (missing) | 1576 |

| >0.8 | Runa Pocito or Otumpa | 1803 |

| 4.21 | el Toba | 1923 |

| 0.025 | el Hacha | 1924 |

| 0.732 | el Mocovi | 1925 |

| 0.85 | el Tonocote | 1931 |

| 0.46 | el Abipon | 1936 |

| 1 | el Mataco | 1937 |

| 2 | el Taco | 1962 |

| 1.53 | la Perdida | 1967 |

| 3.12 | Las Viboras | 1967 |

| 37 | el Chaco | 1969 (extracted in 1980) |

| >10 | Tañigó II (missing) | 1997 |

| 15 | la Sorpresa | 2005 |

| 7.85 | el Wichí or Meteorito Santiagueño | 2006 |

See also

References

- ↑ Field Guide to Meteors and Meteorites by O. Richard Norton and Lawrence Chitwood, Springer, 2008. Page 67. ISBN 9781848001565

- ↑ M. R. Celis (1788). "An account of a mass of native iron found in South America". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society 78: 183–189. doi:10.1098/rstl.1788.0004.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Gerald Joseph Home McCall, A. J. Bowden, Richard John Howarth (2006). The history of meteoritics and key meteorite collections. Geological Society. pp. 28–30. ISBN 978-1-86239-194-9.

- ↑ S. R. Giménez Benítez et al. "Meteoritos de Campo del Cielo: Impactos en la cultura aborigen".

- ↑ "Campo del Cielo". Planetarium de Montreal. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- ↑ Danny Aeberhard, Andrew Benson, Rough Guides, Lucy Phillips (2000). The Rough Guide to Argentina. Rough Guides. p. 370. ISBN 1-85828-569-0.

- ↑ Peter T. Bobrowsky, Hans Rickman (2007). Comet/asteroid impacts and human society: an interdisciplinary approach. Springer. pp. 30–31. ISBN 3-540-32709-6.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Vagn F. Buchwald (1975). The Handbook of Iron Meteorites, Their History, Distribution, Composition and Structure 2. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-02934-8.

- ↑ Monica M. Grady, A. L. Graham, Natural History Museum (London, England) (2000). Catalogue of meteorites. Cambridge University Press. p. 126. ISBN 0-521-66303-2.

- ↑ S.P. Wright et al. (2006). "Revisiting the Campo del Cielo, Argentina crater field: A new data point from a natural laboratory of multiple low velocity, oblique impacts" (PDF). Lunar and Planetary Science. XXXVII: 1102.

- ↑ M. C. L. Rocca et al. (2006). "A catalogue of large meteorite specimens from Campo del Cielo meteorite shower, Chaco province, Argentina" (PDF). 69th Annual Meteoritical Society Meeting: 5501.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Campo del Cielo. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||