Callorhinchidae

| Callorhinchidae | |

|---|---|

| |

| Callorhinchus milii | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Order: | Chimaeriformes |

| Family: | Callorhinchidae Garman, 1901 |

| Genus: | Callorhinchus Lacépède, 1798 |

| Species | |

|

C. callorynchus | |

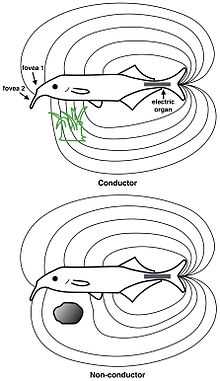

The Callorhinchidae (sometimes spelled "Callorhynchidae"), or plough-nose chimaeras, are a family of marine fish containing one genus, Callorhinchus. They are similar in form and habits to other chimaeras, but are distinguished by the presence of an elongated, flexible, fleshy snout, with a vague resemblance to a ploughshare. The snout is used to probe the sea bottom in search of the invertebrates and small fishes on which it preys.[2] The remainder of the body is flat and compressed, often described as elongated. The mouth is just under this snout and the eyes are located high on top of the head. The usual color is black or brown, and, often a mixture between the two. Phylogenetically, they are the oldest group of living jawed chondrichthyes. They possess the same cartilaginous skeleton seen in sharks but are considered holocephali to distinguish them from the shark and ray categorization. [3] Because of this, they provide a useful research organism for studying the early development of the jawed characteristic. Among the Chondrichthyes genome, Callorhinchus has the smallest genome. Because of this, it has been proposed to be used for entire genome sequencing to represent the cartilaginous fish class. [4] They are considered to be a cross between a shark and a ray or skate, but can be distinguished from sharks because they possess an operculum over their gill slits. Additionally, their skin is smooth, not covered in tough scales, characteristic of the shark. While the shark's jaw is loosely attached to the skull, the Callorhinchidae family differ in that their jaws are fused to their skulls. Many classify the Callorhinchidae as a chimeric species due to their shared characteristics of both the sharks and rays.[5] They are found in muddy and sandy substrates of the ocean bottom, where they filter feed, with small shellfish making up the bulk of their diet. They have broad flat teeth that have adapted for this type of eating habit, two pair that reside in the upper jaw and one pair in the lower jaw. In addition to its utilization for feeding, the trunk of the Callorhinchus fish can sense movement and electric fields, allowing them to locate their prey.[6] They possess large pectoral fins, believed to aid in moving swiftly through the water. They also have two dorsal fins spaced widely apart, which help identify the species in the open ocean.[6] The average length of the fish is estimated to be 70 cm with a maximum length of 130 cm. Average maturation time is 2–3 years, and the average lifespan is about 15 years. This is considered a long maturation span, relative to the Chondricthyes.[7]

Plough-nose chimaeras are found only in the oceans of the Southern Hemisphere, and range from about 70 to 125 cm (2.30 to 4.10 ft) in total length.[8]

Distinctive features

While the club-like snout makes the elephantfish easy to recognize, they have several other distinctive features. The eyes, set high on the head, are often green in color. In front of each pectoral fin is one single gill opening. Between the two dorsal fins is a spine, and the second dorsal fin is significantly smaller than the more anterior one. The caudal fin is divided into two lobes, the top one being larger.[11]

Distribution

Callorhinchus milii is most often found in the southwestern Pacific Ocean near the coasts of Australia and New Zealand in warmer, more temperate waters. Still, in these temperate waters, the elephantfish will reside in the cooler continental shelf. During the spring and summer, C. milii migrates to estuaries and inshore bays to mate.[11]

Callorhinchus callorynchus resides mostly in the Central and South American waters. It is fished for yearround in the waters off of Brazil and Argentina.[12]

Physiology

Fish of the Callorhinchidae family possess a central nervous system and also an immunity that can readily adapt. The brain size to body weight ratio is higher than that of a human. Contrary to humans, it has a larger cerebellum than forebrain. Its vision is very poor and the electrical sensing capabilities of the snout are predominantly used to find food. Both its circulatory and endocrine systems are similar to other similar vertebrates. This makes sense due to the early homologous structures the Callorhinchidae possess relative to the other Chondrichthyes.[13]

Diet

The Callorhinchidae are predominately filter feeders, feeding on the sandy sediment of the ocean bottoms or continental shelfs. The large protrusion of the snout aids in this task. Their diet consists of molluscs, more specifically, clams. Besides this, Callorhinchidae have been shown to also feed on invertebrates such as jellyfish or small octopuses. They are considered to be incapable of eating bony fish, in that they cannot keep up with the teleost's speed.[14]

Reproduction

The Callorhinchidae are oviparous. Mating and spawning happens during the spring and early summer. Males possess the characteristic claspers near the pelvic fin that are seen in sharks, and these are used to transport the gametes. They migrate to more shallow waters to spawn. Also, a club-like protrusion from the head is used to hold onto the female during mating. The keratinous eggs are released onto the muddy sediment of the ocean bottom, usually in shallower water. At first, the egg is a golden yellow color, but this transforms into brown, and finally, black right before hatching. The average amount of time in the egg is 8 months, and the embryo uses the yolk for all nourishment. Once hatched, the young will innately move to deeper water.[12] The eggs are long and flat, and they are often compared to long pieces of seaweed.[15]

Species

The family contains three species, all in the same genus:[8]

- Callorhinchus callorynchus Linnaeus, 1758 (Ploughnose chimaera, American elephantfish, or cockfish)

- Callorhinchus capensis A. H. A. Duméril, 1865 (Cape elephantfish)

- Callorhinchus milii Bory de Saint-Vincent, 1823 (Australian ghostshark)

Fishery and conservation effort

Currently, no effort is being made to conserve the Callorhinchidae family, but the species are heavily fished for food in South America. Because of this, they are extremely susceptible to being overfished. The greatest risk to this species is trawling or net fishing. Using this method, large numbers are caught quickly. Once caught, the fish are sold as whitefish or silver trumpeter fillets, most often served in fish and chips. The most common location of export is Australia. Under the World Conservation Union (IUCN), Callorhinchidae are listed as "Least Concern". While fishing quotas are in place in Australia and New Zealand, this is the furthest that the conservation effort spans. Rarely, they are caught to be placed in aquariums, but this is much less common than fishery for food.[16]

References

- ↑ Otero, Rodrigo A.; Rubilar-Rogers, David; Yury-Yanez, Roberto E.; Vargas, Alexander O.; Gutstein, Carolina S.; Mourgues, Francisco Amaro; Robert, Emmanuel (2013). "A new species of chimaeriform (Chondrichthyes, Holocephali) from the uppermost Cretaceous of the López de Bertodano Formation, Isla Marambio (Seymour Island), Antarctica". Antarctic Science 25 (1): 99–106. doi:10.1017/S095410201200079X.

- ↑ Stevens, J. & Last, P.R. (1998). Paxton, J.R. & Eschmeyer, W.N., ed. Encyclopedia of Fishes. San Diego: Academic Press. p. 69. ISBN 0-12-547665-5.

- ↑ "Elephant Shark Genome Sequencing".

- ↑ "Elephant Shark Genome Sequencing".

- ↑ "Chimaerids, elephant fish and ghost sharks". Sea Friends. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 milii.html "Elephant Fish: Callorhinchus Milii". Fish Index. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- ↑ Luna, Susan. "Callorhinchus callorynchus (Linnaeus, 1758): Plownose chimaera". English Fish Base. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2009). "Callorhincidae" in FishBase. January 2009 version.

- ↑ Heiligenberg, Walter (1977) Principles of Electrolocation and Jamming Avoidance in Electric Fish: A Neuroethological Approach Springer-Verlag. ISBN 9780387083674.

- ↑ Lewicki, M. S., Olshausen, B. A., Surlykke, A., & Moss, C. F. (2014) "Scene analysis in the natural environment". Frontiers in psychology: 5. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00199 Full text

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Bester, Cathleen. "Biological Profile: Ghost Shark". Florida Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Dagit, D.D. "Callorhinchus callorynchus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013. Retrieved 28 September 2013.

- ↑ Warren, Wes. "Genome: Callorhinchus milii". The Genome Institute at Washington University. Retrieved 28 September 2013.

- ↑ Wilson, Judith. "Elephant Sharks". Critters. Retrieved 28 October 2013.

- ↑ Powell, Arthur. "Elephant Fish". Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 28 September 2013.

- ↑ we-do/publications/-best-fish-guide-/elephant-fish "Best Fish Guide:Elephant Fish". Forest and Bird. Retrieved 28 September 2013.