C. E. M. Joad

| C. E. M. Joad | |

|---|---|

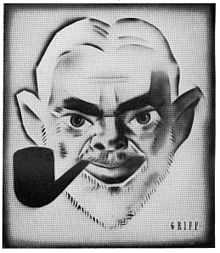

Caricature of Joad (1945) | |

| Born |

12 August 1891 Durham, England |

| Died |

9 April 1953 (aged 61) Hampstead, England |

| Nationality | English |

| Alma mater | Balliol College, Oxford |

| Era | Mid-twentieth century |

| Region | Western philosophy |

|

Influences

| |

Cyril Edwin Mitchinson Joad (12 August 1891 – 9 April 1953) was an English philosopher and broadcasting personality. He appeared on The Brains Trust, a BBC Radio wartime discussion programme. He managed to popularise philosophy and became a celebrity, before his downfall in a scandal over an unpaid train ticket in 1948.[1]

Early life

Joad was born in Durham, the only son of Edwin and Mary Joad (née Smith). In 1892 his father became an Inspector of Schools and the family moved to Southampton, where he received a very strict Christian upbringing. Joad started school at the age of five in 1896, attending Oxford Preparatory School (later called the Dragon School) until 1906, and then Blundell's School, Tiverton, Devon, until 1910.

Balliol College

In 1910, Joad went to Balliol College, Oxford. It was here that he developed his skills as a philosopher and debater. By 1912, he was a first class sportsman and Oxford Union debater. He also became a Syndicalist, a Guild Socialist and then a Fabian. In 1913, he heard about George Bernard Shaw through the newly founded magazine, the New Statesman. He developed an interest in philosophy that acted as the building blocks for his career as a teacher and broadcaster. After completing his course at Balliol, achieving a first in classical moderations (1912),[2] a first in Greats (a combination of philosophy and ancient history, 1914) and John Locke scholarship in mental philosophy (1914), Joad entered the civil service.[3]

Civil service

Joad entered the Board of Trade in 1914 after attending a Fabian Summer School. His aim was to infuse the civil service with a socialist ethos. He worked as a civil servant for the Labour Exchanges Department of the Board of Trade, which later became the Ministry of Labour. In the months leading up to the First World War he displayed "ardent" pacifism, which resulted in political controversy.[4] Joad, along with Bernard Shaw, and Bertrand Russell became unpopular with many who were trying to encourage soldiers to fight for their country.

Marriage

In May 1915, Joad married Mary White and they bought a home in Westhumble near Dorking in Surrey. The village, formerly home to Fanny Burney, was near to the founder of the Fabian Society, Beatrice Webb. Joad was so fearful of conscription that he fled to Snowdonia, Wales until it was safe to return. After the birth of three children, Joad's marriage ended in separation in 1921. Joad later caused some controversy by stating his separation had caused him to abandon his feminism and instead adopt a belief in the "inferior mind" of women.[4]

Life after separation

After the separation Joad moved to Hampstead in London with a student teacher named Marjorie Thomson. She was to be the first of many mistresses, all of whom were introduced as 'Mrs Joad'. He described sexual desire as "a buzzing bluebottle that needed to be swatted promptly before it distracted a man of intellect from higher things." He believed that female minds lacked objectivity, and he had no interest in talking to women who would not go to bed with him. By now Joad was "short and rotund, with bright little eyes, round, rosy cheeks, and a stiff, bristly beard." He dressed in shabby clothing as a test: if people sneered at this they were too petty to merit acquaintance.

Job interviews proved a great difficulty for Joad due to his flippancy. In 1930, however, he left the civil service to fill the post of Head of the Department of Philosophy and Psychology at Birkbeck College, University of London. Although the department was small, he made full use of his great teaching skills. He popularised philosophy, and many other great philosophers of the day were beginning to take him seriously. For those that did not, Joad implied that they resented a blackleg who admitted outsiders to professional mysteries. With his two books, Guide to Modern Thought (1933) and Guide to Philosophy (1936), he became a well-known figure in public society.

1930s

In his early life, Joad very much shared the desire for the destruction of the Capitalist system. He was expelled from the Fabian Society in 1925 because of sexual misbehaviour at its summer school, and did not rejoin until 1943. In 1931, disenchanted with Labour in office, Joad became Director of Propaganda for the New Party. Owing to the rise of Oswald Mosley's Pro-Fascist sympathies, Joad resigned, along with John Strachey. Soon after he became bitterly opposed to Nazism, but he continued to refuse military service and he gave his support to a number of pacifist organisations.

Joad was an outspoken controversialist; he declared his main intellectual influences were George Bernard Shaw and H. G. Wells.[4] Joad was strongly critical of contemporary philosophical trends such as Marxism, Behaviorism and Psychoanalysis.[4] Joad was repeatedly referred to as "the Mencken of England", although as Kunitz and Haycraft pointed out, Joad and Mencken "would be at sword's point on most issues".[4]

While at Birkbeck College, Joad became a participant in the The King and Country debate. The motioned devised by David Graham and debated on Thursday, 9 February 1933 was "that this House will in no circumstances fight for its King and Country.” The topic was often interpreted as illustrating both the attitude of Oxford and the state of Europe at the time; Adolf Hitler had become chancellor of Germany just ten days prior to the debate. Joad was the principal speaker in favour of the resolution, which passed by a vote of 275 to 153. Joad’s speech was described as “well-organized and well-received, and probably the single most important reason for the outcome of the debate.”[5]

Joad was also interested in the supernatural and partnered Harry Price on a number of ghost-hunting expeditions, also joining the Ghost Club of which Price became the president. He involved himself in psychical research, travelling to the Harz Mountains to help Price to test whether the 'Bloksberg Tryst' would turn a male goat into a handsome prince at the behest of a maiden pure in heart; it did not.[6] In 1934 he became Chairman of the University of London Council for Psychical Investigation, an unofficial committee formed by Price as a successor body to his National Laboratory of Psychical Research.[7] In 1939 Joad's publications in psychical research were severely criticised in the Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research[8] and Price suspended the operations of the Council.[9] Joad opposed the spiritualist hypothesis of mediumship.[10]

Joad crusaded to preserve the English countryside against industrial exploitation, ribbon development, overhead cables and destructive tourism. He wrote letters and articles in protest of the decisions being made to increase Britain's wealth and status, as he believed the short term status would bring long term problems. He organised rambles and rode recklessly through the countryside. He also had a passion for hunting.

Hating the idea of nothing to do, Joad organised on average nine lectures per week and two books per year. His popularity soared and he was invited to give many lectures and lead discussions. He also involved himself in sporting activities such as tennis and hockey, and recreational activities such as bridge, chess and playing the pianola (the player piano). He was a great conversationalist and enjoyed entertaining the distinguished members of society.

After the outbreak of the Second World War he became disgusted at the lack of liberty being shown. He went as far as to beg the Ministry of Information to make use of him. In January 1940, Joad was selected for a BBC wartime discussion programme called The Brains Trust which was an immediate success, attracting millions of listeners.

The Brains Trust

Joad's prominence came from The Brains Trust which featured a small group that included Commander A. B. Campbell and Julian Huxley. His developed and matured discussion techniques, his fund of anecdotes and mild humour brought him to the attention of the general public.

The programme came to deal with difficult questions posed by listeners, and the panellists would discuss the question in great detail, and render a philosophical opinion. Examples of the questions ranged from "What is the meaning of life?" to "How can a fly land upside-down on the ceiling?" Joad became a star of the show, his voice being the most heard on radio except for the news. Joad nearly always opened with the catchphrase "It all depends on what you mean by…" when responding to a question. Although there was opposition from Conservatives who complained about the political bias, the general public generally considered him the greatest British philosopher of the day and celebrity status followed.

Rise and fall

As Joad had become so well known, he was invited to give after-dinner speeches, open bazaars and even advertise tea and his book sales soared. He stood as a Labour candidate at a by-election in November 1946 for the Combined Scottish Universities constituency but lost.

Joad once boasted in print that "I cheat the railway company whenever I can."[11] On 12 April 1948, Joad was caught travelling on a Waterloo to Exeter train without a valid ticket.[12] When he failed to give a satisfactory excuse, he was convicted of fare dodging and fined £2 (£63 as of 2015). This made front-page headlines in the national newspapers, destroyed his hopes of a peerage and resulted in his dismissal from the BBC.[13] The humiliation of this had a severe effect on Joad's health, and he soon became bed-confined at his home in Hampstead. Joad renounced his agnostic ways and returned to the Christianity of the Church of England, which he detailed in his book The Recovery of Belief published in 1952.[14]

Death

After the bed-confining thrombosis following his dismissal from the BBC in 1948, Joad developed terminal cancer. Joad died on 9 April 1953 at his home, 4 East Heath Road, Hampstead aged 61 and was buried at Saint John's-at-Hampstead Church in London.

Legacy

Joad was one of the best known British intellectuals of his time, as well known as George Bernard Shaw and Bertrand Russell in his lifetime. He popularised philosophy, both in his books and by the spoken word.

Quotes from Joad appear in Virginia Woolf's non-fiction piece, Three Guineas. For example:

"If it is, then the sooner they give up the pretence of playing with public affairs and return to private life the better. If they can not make a job of the House of Commons, let them at least make something of their own houses. If they can not learn to save men from the destruction which incurable male mischievousness bids fair to bring upon them, let women at least learn to feed them, before they destroy themselves."[15]

His leading role in a high profile debate of the Oxford Union Society also helped to establish his legacy, which helped to make him a reputation as an absolute pacifist, a position which the Nazi menace of the Second World War caused him to set aside.

Joad was invited to appear at the Socratic Club, an undergraduate society at Oxford University, where he spoke on 24 January 1944, on the subject, of "On Being Reviewed by Christians," an event attended by more than 250 students. This was a stepping stone in Joad's life, particularly at a time when he was re-examining his convictions. This re-examination eventually led to his return to the Christian faith of his youth, an event that he mentioned in his book, The Recovery of Belief, which was published in 1952. C. S. Lewis, President of the Socratic Club, is mentioned twice in this book, once as an influence on Joad through Lewis's book The Abolition of Man. Part of his legacy, then, was to return to the faith that he had set aside as an Oxford undergraduate and to defend that faith in his writings.

He is also mentioned in Stephen Potter's book, Gamesmanship, as his partner in a tennis match in which the two men were up against two younger and fitter players who were outplaying them fairly comfortably, when Joad questioned his opponent whether a ball that he had clearly thrown way behind the line was in or out; an event which Potter says made him start thinking about the concept of gamesmanship.

Selected publications

Joad wrote, introduced or edited over 100 books, pamphlets, articles and essays including:

- Books and pamphlets

- 'Monism in the Light of Recent Developments in Philosophy', Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, N.S. 17 (1916–17)

- 'Robert Owen, Idealist', London : Fabian Society [Tract 182] (1917)

- The Diary of a Dead Officer, Being the Posthumous papers of A.G. West, ed. with intro, London : George Allen & Unwin (1918)

- Essays in Common-Sense Philosophy, London : George Allen & Unwin (1919, 2nd ed., London : GA & U (1933))

- Common Sense Ethics, London : Methuen (1921)

- Common Sense Theology, London : T. Fisher Unwin (1922)

- The Highbrows, A Novel, London : Jonathan Cape (1922)

- Introduction to Modern Political Theory, Oxford : The Clarendon Press (1924)

- Priscilla and Charybdis, and Other Stories, London : Herbert Jenkins (1924)

- Samuel Butler (1835–1902), London : Leonard Parson (1924)

- 'A Realist Philosophy of Life', Contemporary British Philosophy, Second Series, ed. J.H. Muirhead, London : George Allen & Unwin (1925)

- Mind and Matter : The Philosophical Introduction to Modern Science, London : Nisbet (1925)

- The Babbitt Warren [A Satire on the United States], London : Kegan Paul (1926)

- The Bookmark, London : The Labour Publishing Company (1926, repr. London : Westhouse (1945))

- Diogenes, The Future of Leisure, London : Kegan, Paul, Trench, Trubner (1928)

- Thrasymachus, The Future of Morals, London : Kegan, Paul, Trench, Trubner (1928, rev. ed., London : Kegan Paul (1936))

- The Future of Life : A Philosophy of Vitalism, New York : G.P. Putnam's Sons (1928)

- The Meaning of Life As Shown in the Process of Evolution, London : Watts & Co. (1928)

- Great Philosophies of the World, London : Ernest Benn (1928, repr.& rev., London : Thomas Nelson (1937))

- Matter, Life and Value, London : Oxford University Press (1929)

- 'Philosophy and Aldous Huxley', The Realist, 1: 4 (1929)

- The Present and Future of Religion, London : Ernest Benn (1930)

- Unorthodox Dialogies on Education and Art, London : Ernest Benn (1930)

- 'The Case for the New Party', London : New Party (c. 1931)

- The Story of Civilization, London : A. & C. Black (1931)

- Guide to Modern Thought, London : Faber & Faber (1933, rev. & enlarged, London : Pan (1948))

- Philosophical Aspects of Modern Science, London : George Allen & Unwin (1932, repr. London : GA&U (1963))

- Under the Fifth Rib, London : Faber & Faber (1932), retitled The Book of Joad (1935)

- Counter Attack from the East : The Philosophy of Radhakrishnan, London : George Allen & Unwin (1933)

- Liberty Today, London : Watts (1934)

- Manifesto : Being the Book of the federation of Progressive Societies and Individuals, ed., London : George Allen & Unwin (1934)

- 'The End of an Epoch', New Statesman & Nation, London (8 December 1934)

- Return to Philosophy, London : Faber & Faber (1935)

- 'Science and Human Freedom', London : Haldane Memorial Lecture (1935)

- 'The Challenge to Reason', The Rationalist Annual, London : The Rationalist Press (1935)

- Guide to Philosophy, London : Victor Gollancz (1936)

- The Dictator Resigns, London : Methuen (1936)

- 'The Return of Dogma', The Rationalist Annual, London : The Rationalist Press (1936)

- The Story of Indian Civilisation, London : Macmillan (1936)

- '"Defence" is No Defence, London : National Peace Council (1937)

- 'On Pain, Death, and the Goodness of God', The Rationalist Annual, London : The Rationalist Press (1937)

- The Testament of Joad, London : Faber & Faber (1937)

- Guide to the Philosophy of Morals and Politics (1938)

- How to Write, Think and Speak Correctly, ed., London : Odhams (1939)

- 'On Useless Education',The Rationalist Annual, London : The Rationalist Press (1939)

- Why War?, Harmondsworth : Penguin (1939)

- For Civilization, London : Macmillan (1940)

- Journey Through the War Mind, London : Faber & Faber (1940)

- Philosophy For Our Times, London : Thomas Nelson & Sons (1940)

- 'Principles of Peace', The Spectator, London (16 August 1940; repr. Articles of War : The Spectator Book of World War II, ed. F. Glass & P. Marsden-Smedley, London : Paladin Grafton Books, 1989, 119–22)

- The Philosophy of Federal Union, London : Macmillan (1941)

- What Is at Stake, and Why Not Say So ?, London : Victor Gollancz (1941)

- An Old Countryside for New People, London : J. M. Dent & Sons (1942)

- God and Evil, London : Faber & Faber (1942)

- Pieces of Mind, London : Faber & Faber (1942)

- 'The Face of England', Horizon, V, London (29 May 1942)

- The Adventures of the Young Soldier in Search of the Better World, London : Faber & Faber (1943)

- 'Man's Superiority to the Beasts : Liberty Versus Security in the Modern State', Freedom of Expression, ed. H. Ould, London : Hutchinson, International Authors Ltd (1944)

- 'On Thirty Years of Going to the Lakes', Countrygoer Book, ed. C. Moore, London : Countrygoer Books (1944)

- Teach Yourself Philosophy, London : English Universities Press (1944)

- 'The Virtue of Examinations', New Statesman & Nation, London (11 March 1944; reply to objections, 25 March)

- About Education, London : Faber & Faber (1945)

- Joad's Opinions, London : Westhouse (1945)

- Conditions of Survival, London : Federal Union (1946)

- 'Fewer and Better' [Population], London Forum, I : 1, London (1946)

- How Our Minds Work, London : Westhouse (1946)

- 'On No Longer Being A Rationalist', The Rationalist Annual, London : C.A. Watts & Co. (1946)

- The Untutored Townsman's Invasion of the Country, London : Faber & Faber (1946)

- 'Introduction', J.C. Flugel, Population, Psychology, and Peace, London : Watts & Co. (1947)

- 'The Rational Approach to Conscription', London : National Conscription Council, Pamphlet No. 7 (1947)

- A Year More or Less, London : Victor Gollancz (1948)

- Decadence – A Philosophical Inquiry, London : Faber & Faber (1948)

- 'Foreword', Clare & Marshall Brown, FellWalking from Wasdale, London : The Saint Catherine Press (1948)

- The English Counties, London : Odhams (1948)

- 'Turning-Points', The Saturday Book, ed. L. Russell, London : Hutchinson (1948)

- Shaw, London : Victor Gollancz (1949)

- The Principles of Parliamentary Democracy, London : Falcon Press (1949)

- A Critique of Logical Positivism, London : Gollancz (1950)

- The Pleasure of Being Oneself, London : George Weidenfeld & Nicolson (1951)

- A First Encounter with Philosophy, London : James Blackwood (1952)

- The Recovery of Belief, London : Faber & Faber (1952)

- Shaw and Society (Anthology and a Symposium), London : Odhams (1953)

- Folly Farm [posthumous], London : Faber & Faber (1954)

- Articles and essays

- 'The Idea of Public Right', The Idea of Public Right, Being the First Four Essays ... of The Nation Essay Competition, intro. H.H. Asquith, London : George Allen & Unwin, 1918, 95–140 [Written under the pseudonym of 'Crambe Repetita' derived from Juvenal, Satire VI.154 : occidit miseros crambe repetita magistros – (roughly and freely, tr. Geoffrey Thomas) 'Rehashed cabbage – crambe repetita – is wretchedness for poor teachers'. In context, 'The poor teachers have to listen to their pupils regurgitate the same dismal exercises day after day'. It's like perpetually eating the same dull meal.). Joad's authorship is identified on p. vii.)]

References

- ↑ "C. E. M. Joad". Open University. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- ↑ This corrects an error in Geoffrey Thomas, Cyril Joad, p. 8, in which Joad is credited with a first in classical moderations.

- ↑ John Simkin (13 October 2007). "C. E. M. Joad". Spartacus Educational. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Stanley J. Kunitz and Howard Haycraft, Twentieth Century Authors, A Biographical Dictionary of Modern Literature, (Third Edition). New York, The H.W. Wilson Company, 1950, (p.p. 726-7)

- ↑ Martin Ceadel, “The ‘King and Country’ Debate, 1933: Student Politics, Pacifism and the Dictators.” The Historical Journal, June 1979, 404.

- ↑ Trevor Hall (Oct 1978). Search for Harry Price. Gerald Duckworth and Company. pp. 160–170. ISBN 0-7156-1143-7.

- ↑ Harry Price (2003). Fifty Years of Psychical Research (reprint ed.). Kessinger Publishing. p. 64. ISBN 0-7661-4242-6.

- ↑ "Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research" 45. 1939. p. 217.

- ↑ Hall, op. cit., pp.170–173

- ↑ Shaw Desmond and Cyril Edwin Mitchinson Joad. (1946). Spiritualism. By S. Desmond-for- & C.E.M. Joad-against. Muse Arts

- ↑ C.E.M. Joad, The Testament of Joad, 54

- ↑ Cyril Edwin Mitchinson "C.E.M." Joad (1891–1953) – Find A Grave Memorial

- ↑ Sean Street (2009). The A to Z of British Radio. Scarecrow Press. p. 150. ISBN 0-8108-6847-4.

- ↑ The Recovery of Belief (work by Joad) – Britannica Online Encyclopedia

- ↑ Virginia Woolf, Three Guineas, p43.

Further reading

- Judge, Tony, Radio Philosopher: The Radical Life of Cyril Joad, (Charleston NC 2012)

- Martin, Kingsley, 'Cyril Joad', New Statesman and Nation, London : 18 April 1953

- Martin, Kingsley Editor : A Volume of Autobiography 1931–1945, (London: Hutchinson 1968), esp. pp. 135–9

- Plant, Kathryn. L, 'Joad, Cyril Edwin Mitchinson (1891–1953)', in The Dictionary of Twentieth-Century British Philosophers, ed. Stuart Brown, (Thoemmes Continuum, Bristol 2005), vol. I, pp. 480–482

- Thomas, Geoffrey Cyril Joad, (Birkbeck College Publication 1992)

External links

|