Burusho people

|

A Hunza Rajah and Tribesmen in 19th century. | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 87,000 (2000) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Pakistan | |

| Languages | |

| Burushaski, Urdu[1] | |

| Religion | |

| Islam, Historically Shamanism[2] |

The Burusho or Brusho people live in the Hunza and Yasin valleys of Gilgit–Baltistan in northern Pakistan.[3] They are predominantly Muslims. Their language, Burushaski, has not been shown to be related to any other.[4]

Hunza

The Hunzakuts or Hunza people, are an ethnically Burusho people indigenous to the Hunza Valley, in the Karakorum Mountains of northern Pakistan. They are descended from inhabitants of the former principality of Hunza. The Burusho claim to be descendants of the soldiers who came to the region with Alexander the Great's army in the 4th century BC.

The Hunzas are Shia Ismaili Muslims.[7]

DNA research groups the people of Hunza with Sinti Romani (Gypsies) and the speakers of Bartangi (Pamir language), due primarily to the M124 marker (defining Y-DNA haplogroup R2a), which is present at high frequency in all three populations.[8] However, they have also an East Asian genetic contribution, suggesting that at least some of their ancestry originates north of the Himalayas.[9]

Hunzakuts and the Hunza region have relatively high literacy rates, compared to similar districts in Pakistan. Hunza is a major tourist attraction in Pakistan, and many Pakistani as well as foreign tourists travel to the region to enjoy the picturesque landscape and stunning mountains of the area. The district has many modern amenities and is quite advanced by Asian standards. Local legend states that Hunza may have been associated with the lost kingdom of Shangri-La. The people of Hunza are by some noted for their exceptionally long life expectancy,[10] others describe this as a longevity narrative and cite a life expectancy of 53 years for men and 52 for women, although with a high standard deviation.[11]

The Hunzakuts live alongside the Wakhi and the Shina. The Wakhi reside in the upper part of Hunza locally called Gojal. Wakhis also inhabit the bordering regions of China, Tajikstan and Afghanistan and also live in Gizar and Chitral district of Pakistan. The Shina-speaking people live in the southern part of Hunza. They have come from Chilas, Gilgit, and other Shina-speaking areas of Pakistan.

Theories of Greek heritage

Burusho legend maintains that they descend from the village of Baltir, which had been founded by a soldier left behind from the army of Alexander the Great—a legend common to much of northern Pakistan.[12] However, genetic evidence supports only a very small, 2% Greek genetic component among the Pashtun ethnic group of Pakistan and Afghanistan,[13] not the Burusho.[14]

The Hunza and the Republic of Macedonia

In 2008 the Macedonian Institute for Strategic Researches "16.9" organized a visit by Hunza Prince Ghazanfar Ali Khan and Princess Rani Atiqa as descendants of the Alexandran army.[15] The Hunza delegation was welcomed at the Skopje Airport by the country's prime minister Nikola Gruevski, the head of the Macedonian Orthodox Church Archbishop Stephen and the then-mayor of Skopje Trifun Kostovski. Academics dismiss the idea as pseudoscience and doubts exist that party leaders actually believe the claims either.[16]

Genetics

A variety of NRY haplogroups are seen among the Burusho. Most frequent among these are R1a1 - a lineage associated with Indoeuropean and likely related to the Bronze Age migration into South Asia c. 3000 BCE;[17] and R2a,[18] probably originating in South/Central Asia during the Upper Paleolithic. The subcontinental lineages of haplogroup H1 and haplogroup L3 are also present,[18] although haplogroup L, defined by SNP mutation M20, reaches a maximum of diversity in Pakistan.[19] Other Y-DNA haplogroups reaching considerable frequency are haplogroup J2, associated with the spread of agriculture in, and from, the neolithic Near East,[17][18] and haplogroup C3, of Siberian origin and possibly representing the patrilineage of Genghis Khan. Also present at lower frequency are haplogroups O3, an East Eurasian lineage, and Q, P, F, and G.[18]

Influence in the Western world

Healthy living advocate J. I. Rodale wrote a book called The Healthy Hunzas in 1955 that asserted that the Hunzas, noted for their longevity and many centenarians, were long-lived because of their consumption of healthy organic foods such as dried apricots and almonds, as well as their getting plenty of fresh air and exercise.[20] He often mentioned them in his Prevention magazine as exemplary of the benefits of leading a healthy lifestyle.

Dr. John Clark stayed among the Hunza people for 20 months and in his book Hunza - Lost Kingdom of the Himalayas[21] writes: “I wish also to express my regrets to those travelers whose impressions have been contradicted by my experience. On my first trip through Hunza, I acquired almost all the misconceptions they did: The Healthy Hunzas, the Democratic Court, The Land Where There Are No Poor, and the rest—and only long-continued living in Hunza revealed the actual situations”. Regarding the misconception about Hunza people's health, John Clark also writes that most of patients had malaria, dysentery, worms, trachoma, and other things easily diagnosed and quickly treated; in his first two trips he treated 5,684 patients.

Furthermore, Clark reports that Hunza do not measure their age solely by calendar (metaphorically speaking, as he also said there were no calendars), but also by personal estimation of wisdom, leading to notions of typical lifespans of 120 or greater.

The October 1953 issue of National Geographic had an article on the Hunza River Valley that inspired Carl Barks' story Tralla La.[22]

Renée Taylor wrote several books in the 1960s, treating the Hunza as a long-lived and peaceful people.[23]

See also

References

- ↑ "TAC Research The Burusho". Tribal Analysis Center. 30 June 2009.

- ↑

- ↑ "Jammu and Kashmir Burushaski : Language, Language Contact, and Change". Repositories.lib.utexas.edu. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- ↑ "Burushaski language". Encyclopædia Britannica online.

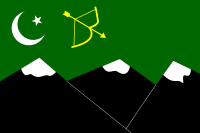

- ↑ "Hunza". Flags of the World. 7 June 2008. Retrieved 19 June 2010.

- ↑ "Flag Spot Hunza (Pre-independence Pakistan)". Flagspot.net.

- ↑ David Hatcher Childress (1998). Lost cities of China, Central Asia, & India. Adventures Unlimited Press. p. 263. ISBN 0-932813-07-0. Retrieved 2011-01-23.

- ↑ R. Spencer Wells et al., The Eurasian Heartland: A continental perspective on Y-chromosome diversity, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America

- ↑ Jun Z. Li et al., Worldwide human relationships inferred from genome wide patterns of variation - Science, Vol. 319. no. 586 (22 February 2008), pp. 1100 - 1104.

- ↑ Wrench, Dr Guy T (1938). The Wheel of Health: A Study of the Hunza People and the Keys to Health. 2009 reprint. Review Press. ISBN 978-0-9802976-6-9. Retrieved 12 August 2010

- ↑ Tierney, John (29 September 1996). "The Optimists Are Right". The New York Times.

- ↑ An Ethnohistorical Dictionary of China. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1998, ISBN 0-313-28853-4. Books.google.bg. 1998-01-01. ISBN 9780313288531.

- ↑ Y-chromosomal evidence for a limited Greek contribution to the Pathan population of Pakistan, European Journal of Human Genetics (2007) 15; published online 18 October 2006

- ↑ Y-Chromosomal DNA Variation in Pakistan, American Journal of Human Genetics, 70:1107–1124, 2002, pg. 117

- ↑ Neil MacDonald (18 July 2008). "Alexander's 'descendants' boost Macedonian identity". Financial Times.

- ↑ "2,300 years later, 'Alexander-mania' grips Macedonia". The Christian Science Monitor.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 R. Spencer Wells et al., "The Eurasian Heartland: A continental perspective on Y-chromosome diversity," Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (August 28, 2001)

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 Firasat, Sadaf; Khaliq, Shagufta; Mohyuddin, Aisha; Papaioannou, Myrto; Tyler-Smith, Chris; Underhill, Peter A; Ayub, Qasim (2006). "Y-chromosomal evidence for a limited Greek contribution to the Pathan population of Pakistan". European Journal of Human Genetics 15 (1): 121–6

- ↑ Qamar Raheel et al. "Y-Chromosomal DNA Variation in Pakistan". American Journal of Human Genetics 70 (1107–1124): 2002.

- ↑ Rodale, J. I. The Healthy Hunzas 1955

- ↑ Clark, John (1956). Hunza - Lost Kingdom of the Himalayas. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. OCLC 536892.

- ↑ The Carl Barks Library Volume 12, page 229

- ↑ Taylor, Renée (1964). Long Suppressed Hunza health secrets for long life and happiness. New York: Award Books.