Burning of Parliament

The Palace of Westminster, the medieval royal palace used as the home of the British parliament, was destroyed by fire of 16 October 1834. The blaze was caused by the burning of small wooden tally sticks which had been used as part of the accounting procedures of the Exchequer until 1826. The sticks were disposed of in a careless manner in the two furnaces under the House of Lords, which caused a chimney fire in the two flues that ran under the floor of the Lords' chamber and up through the walls.

The resulting fire spread rapidly throughout the complex and developed into the biggest conflagration to occur in London between the Great Fire of 1666 and the Blitz of the Second World War; the event attracted massive crowds which included several artists who provided pictorial records of the event. The fire lasted for most of the night and destroyed a large part of the palace, including the converted St Stephen's Chapel—the meeting place of the House of Commons—the Lords Chamber, the Painted Chamber and the official residences of the Speaker and the Clerk of the House of Commons.

The actions of Superintendent James Braidwood of the London Fire Engine Establishment ensured that Westminster Hall and a few other parts of the old Houses of Parliament survived the blaze. After a competition to find a new design for the palace, the plans of Charles Barry—who was aided by Augustus Pugin—incorporated the surviving buildings into the new complex. The competition established the Victorian gothic style of architecture as the national norm, even for secular buildings. The replacement palace has since been classed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site and is classified as being of outstanding universal value.

Background

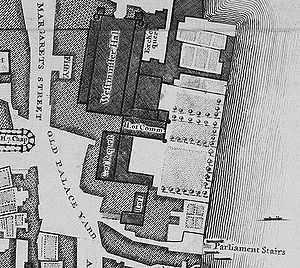

The Palace of Westminster began to be constructed in the first half of the eleventh century when Cnut the Great built his royal residence on the side of the River Thames. Successive kings added to the area: Edward the Confessor built Westminster Abbey; William the Conqueror began building a new palace; his son, William Rufus, continued the process, which included Westminster Hall, which was started in 1097; Henry III built new exchequer buildings in 1270 and the Court of Common Pleas, along with the Court of King's Bench and Court of Chancery. By 1245 the King's throne was present in the palace, which signified that the building was at the centre of English royal administration.[1][2]

In 1295 Westminster was used as the venue for the Model Parliament, the first English representative assembly, summoned by Edward I; he called sixteen parliaments during his reign, which sat either in the Painted Chamber or White Chamber. By 1332 the barons—representing the titled classes—and burgesses and citizens—representing the commons—began to meet separately, and by 1377 the two bodies were entirely detatched.[3][4] In 1512 a fire destroyed part of the royal palace complex and Henry VIII moved the royal residence to the nearby Palace of Whitehall, although Westminster still retained its status as a royal palace. In 1547 Henry's son, Edward VI, provided St Stephen's Chapel for the Commons to use as their debating chamber.[3][5] Over the next three centuries the palace was enlarged and altered to become a warren of wooden passages and stairways.[6]

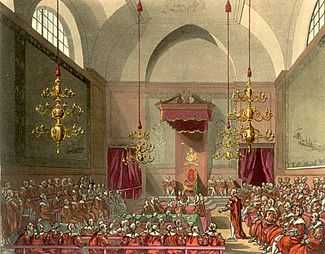

St. Stephen's Chapel remained largely unchanged until 1692 when Sir Christopher Wren, at the time the Master of the King's Works, was instructed to make structural alterations. He lowered the roof, removed the stained glass windows, put in a new floor and covered the original gothic architecture with wood panelling. He also added galleries from which the public could watch proceedings.[7][8][lower-alpha 1] The result was something that one visitor to the chamber called "dark, gloomy, and badly ventilated, and so small ... when an important debate occurred ... the members were really to be pitied".[9] When the future Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone remembered his arrival as a new MP in 1832, he recounted "What I may term corporeal conveniences were ... marvellously small. I do not think that in any part of the building it afforded the means of so much as washing the hands."[10] The facilities were so poor for members, that Joseph Hume, a Radical MP, called debates in 1831 and 1834 to find new accommodation for the House to sit, while his fellow MP William Cobbett asked "Why are we squeezed into so small a space that it is absolutely impossible that there should be calm and regular discussion, even from circumstance alone ... Why are 658 of us crammed into a space that allows each of us no more than a foot and a half square?"[11]

The potential dangers of the building were apparent to some, as no fire stops or party walls were present in the building to slow the progress of the fire.[12] In the late eighteenth century a committee of MPs reported that there would be a disaster if the palace caught fire. This was followed by an 1789 report from fourteen architects warning against the possibility of fire in the palace; signatories included John Soane and Robert Adam.[13] Sloane again warned of the dangers in 1828, when he wrote that "the want of security from fire, the narrow, gloomy and unhealthy passages, and the insufficiency of the accommodations in this building are important objections which call loudly for revision and speedy amendment." His report was again ignored.[14]

Since medieval times the Exchequer—the taxation and revenue gathering department of the country—had used tally sticks, pieces of carved, notched wood, normally willow, as part of their accounting procedures.[15][16] These sticks were split in two so that the two sides to an agreement had a record of the situation.[17] Once the usefulness of each tally had come to an end, they were routinely destroyed.[16] By the end of the eighteenth century the usefulness of the tally system had come to an end, and a 1782 Act of Parliament stated that all records should be on paper, not tallies. The Act also abolished sinecure positions in the Exchequer, but a clause in the act ensured it could only take effect once the remaining sinecure-holders had died or retired.[18] The final sinecure-holder died in 1826 and the act came into force,[16] although it took until 1834 for the antiquated procedures to be replaced.[15][19] The novelist Charles Dickens, in a speech to the Administrative Reform Association, described the retention of the tallies for so long as an "obstinate adherence to an obsolete custom"; he also mocked the machinations needed to implement change from wood to paper. He said that "all the red tape in the country grew redder at the bare mention of this bold and original conception."[20] By the time the replacement process had finished there were two cart-loads of old tally sticks awaiting disposal.[16]

In October 1834 Richard Weobley, the Clerk of Works, received instructions from Treasury officials to clear the old tally sticks while parliament was adjourned. He decided against giving the sticks away to parliamentary staff to use as firewood, and instead opted to burn them in the two heating furnaces of the House of Lords, directly below the peers' chambers.[21][22][lower-alpha 2] The furnaces had been designed to burn coal—which gives off a high heat and little flame—and not wood, which burns with a high flame.[24] The flues of the furnaces ran up the walls of the basement in which they were housed, under the floors of the Lords' chamber, then up through the walls and out through the chimneys.[21]

16 October 1834

of the fire

The process of destroying the tally sticks began at dawn on 16 October and continued throughout the day; two Irish labourers, Joshua Cross and Patrick Furlong, were assigned the task.[25] Weobley checked in on the men throughout the day. He later reported that on his visits both furnace doors were open, which allowed the two labourers to watch the flames, while the piles of sticks in both furnaces were only ever four inches (ten centimetres) high.[26] Another witness to events, Richard Reynolds, the firelighter in the Lords, later reported that he had seen Cross and Furlong throwing handfuls of tallies onto the fire—an accusation they both denied.[27]

What no-one appreciated on the day was that the heat from the fires had melted the copper lining of the flues and started a chimney fire. With the doors of the furnaces open, more oxygen was drawn into the furnaces, which ensured the fire burned more fiercely, and the flames driven further up the flues than they should have been.[28] The flues had been weakened over time by having footholds cut in them by the child chimney sweeps. Although these would have been repaired as the child exited, the fabric of the chimney was still weakened by the action. In October 1834 the chimneys had not yet had their annual sweep, and a considerable amount of clinker had built up inside the flues.[21][29][lower-alpha 3]

A strong smell of burning was present in the Lords' chambers during the afternoon, and at 4:00 pm two gentlemen tourists visiting to see the Armada tapestries that hung there, were unable to view them properly because of the thick smoke. As they approached Black Rod's box in the corner of the room, they felt heat from the floor coming through their boots.[31] Shortly after 4:00 pm Cross and Furlong finished work, put the last few sticks into the furnaces—closing the doors as they did so—and left to go to the nearby Star and Garter public house.[32]

The first flames were spotted at 6:00 pm, under the door of the House of Lords, by the wife of one of the doorkeepers; she entered the chamber to see Black Rod's box alight, and flames burning the curtains and wood panels, and she cried out that "The House of Lords is on fire!"[21][33] For 25 minutes the staff inside the palace panicked and tried to deal with the blaze, but they did not call for assistance, and did not alert staff at the House of Commons, at the other end of the palace complex.[21]

At 6:30 pm there was a flashover,[lower-alpha 4] a giant ball of flame that The Manchester Guardian reported "burst forth in the centre of the House of Lords, ... and burnt with such fury that in less than half an hour, the whole interior ... presented ... one entire mass of fire."[35][36] The explosion, and the resultant burning roof, lit up the skyline, and could be seen by the royal family in Windsor Castle, 20 miles (32 km) away. Alerted by the now highly visible flames, help arrived from nearby parish fire engines; as there were only two hand-pump engines on the scene, they were of limited use.[21][37] They were joined at 6:45 pm by 100 soldiers from the Grenadier Guards, some of whom helped the police in forming a large square in front of the palace to keep the growing crowd back from the firefighters; some of the soldiers assisted the firemen in pumping the water supply from the engines.[38]

The London Fire Engine Establishment (LFEE)—an organisation run by several insurance companies in the absence of a publicly run Brigade—was alerted at about 7:00 pm, by which time the fire had spread from the House of Lords. The head of the LFEE, James Braidwood, brought with him 12 engines and 64 firemen, even though the Palace of Westminster was a collection of uninsured government buildings, and therefore fell outside the protection of the LFEE.[33][39][lower-alpha 5] Some of the firefighters ran their hoses down to the Thames. The river was at low tide and it meant a poor supply of water for the engines on the river side of the building.[40]

By the time Braidwood and his men had arrived on the scene, he realised that the House of Lords had been destroyed. A strong south-westerly breeze had fanned the flames along the wood-panelled and narrow corridors into St Stephen's Chapel.[10][39] Shortly after his arrival the roof of the chapel collapsed, the resultant noise was so loud that the watching crowds thought there had been a Gunpowder Plot-style explosion. According to The Manchester Guardian, "By half-past seven o'clock the engines were brought to play upon the building both from the river and the land side, but the flames had by this time acquired such a predominance that the quantity of water thrown upon them produced no visible effect."[35] Braidwood saw it was too late to save most of the palace, so elected to focus his efforts on saving Westminster Hall, and he had his firemen cut away the part of the roof that connected the hall to the already burning Speaker's House, and then soaking the hall's roof to prevent it catching fire. In doing so he saved the medieval structure at the expense of those parts of the complex already ablaze.[10][39]

The glow from the burning, and the news spreading quickly round London, ensured that a large crowd turned up to watch events. Among them was a reporter for The Times, who noticed that there were "vast gangs of the light-fingered gentry in attendance, who doubtless reaped a rich harvest, and [who] did not fail to commit several desperate outrages."[41] The crowds were so thick that they blocked Westminster Bridge in their attempts to get a good view, and many took to the river in whatever craft they could find or hire to get a better view.[42] A crowd of thousands congregated in Parliament Square to witness the spectacle, including the Prime Minister—Lord Melbourne—and many of his cabinet.[43][44] Thomas Carlyle, the Scottish philosopher, was one of those present that night, and he later recalled that:

"The crowd was quiet, rather pleased than otherwise; whew'd and whistled when the breeze came as if to encourage it: 'there's a flare-up (what we call shine) for the House o' Lords.' —'A judgment for the Poor-Law Bill!' — 'There go their hacts ' (acts)! Such exclamations seemed to be the prevailing ones. A man sorry I did not anywhere see."[45]

This view was doubted by Lord Broughton, the Commissioners of Woods and Forests, who oversaw the upkeep of royal buildings, including the Palace of Westminster. He wrote that "the crowd behaved very well; only one man was taken up for huzzaing when the flames increased. ... on the whole, it was impossible for any large assemblage of people to behave better."[46] Many of the MPs and peers present, including Lord Palmerston, the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, were involved in breaking down doors to rescue books and other treasures, aided by passers-by; the Deputy Serjeant at Arms had to break into a burning room to save the parliamentary mace.[33]

By 9:00 pm three Guards regiments arrived on the scene.[47] Although the troops assisted in crowd control, their arrival was also a reaction of the authorities to fears of a possible insurrection, for which the destruction of parliament could have signalled the first step. The three European revolutions of 1830—the French, Belgian and Polish actions—were still of concern, as was the unrest from the Captain Swing riots, and the recent passing of the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834, which altered the relief provided by the workhouse system.[21][48]

At around 1:30 am the tide on the Thames had risen enough to allow the LFEE's floating fire engine to arrive on the scene. Braidwood had called for the engine five hours previously, but the low tide had hampered its progress from its downriver mooring at Rotherhithe. Once it arrived it was hugely effective in bringing under control the fire that had taken hold in the Speaker's House.[21][49]

Braidwood regarded Westminster Hall as safe from destruction by 1:45 am, partly because of the actions of the floating fire engine, but also because a change in the direction of the wind kept the flames away from the Hall. Once the crowd realised that the hall was safe they began to disperse,[50] and had left by around 3:00 am, by which time the fire near the Hall was nearly gone, although it was still in situ towards the south of the complex.[51] The firemen remained in place until about 5:00 am, when they had extinguished the last remaining flames, by which time the new shifts of police and soldiers relieved their colleagues.[52]

The House of Lords, its robing and committee rooms were all destroyed, as was the Painted Chamber, and the connecting end of the Royal Gallery. The House of Commons, along with its library and committee rooms were also devastated, as was the official residence of the Clerk of the House and the Speaker's House. Many of the other buildings, such as the Law Courts, were damaged and in need of restoration.[53] The surviving buildings of the complex—aside from Westminster Hall—were the Cloisters of St. Stephen's, St Mary Undercroft Chapel and the Jewel Tower.[54] The British standard measurements, the yard and pound, were both lost in the blaze; the measurements had been created in 1496.[55] Also lost were most of the procedural records for the House of Commons, which dated back as far as the late 15th century. All of the original Acts of Parliament from 1497 survived, as did the Lords' Journals, all of which were stored in the Jewel Tower at the time of the fire.[56][57] In the words of Caroline Shenton, the parliamentary historian who has written on the subject, the fire was "the most momentous blaze in London between the Great Fire of 1666 and the Blitz" of the Second World War.[58] Despite the size and ferocity of the fire, there were no deaths, although there were nine casualties during the night's events that were serious enough to require hospitalisation.[59][60]

Aftermath

The day after the fire the Office of Woods and Forests issued a report outlining the damage from the fire which stated that "[t]he strictest enquiry is in progress as to the cause of this calamity, but there is not the slightest reason to suppose that it has arisen from any other than accidental causes."[53] The Times reported on some of the possible causes of the fire, but indicated that it was likely that the burning of the Exchequer tallies was to blame.[53] The same day the cabinet ministers who were in London met for an emergency Cabinet meeting; they instructed a list of witness to be drawn up, and on 22 October a Committee of the Lords of the Privy Council sat to investigate the fire.[27]

The committee, who met in private, heard numerous possibilities of the cause of the fire, including the lax attitude of plumbers working in the Lords, carelessness of the servants at Howard's Coffee House—situated inside the palace—and a gas explosion. More malicious rumours were also reported, when the Prime Minister was anonymously sent a letter claiming it was an arson attack.[61] The committee issued their report on 8 November, which identified the burning of the tallies as the cause of the fire. The committee thought it unlikely that Cross and Furlong had been as careful in filling the furnaces as they claimed, and the report stated that "it is unfortunate that Mr Weobley did not more effectively superintend the burning of the tallies".[62]

King William IV offered Buckingham Palace as a replacement to parliament;[63] the proposal was declined by MPs who considered the building "dingy".[64] Parliament still needed somewhere to meet, and the Lesser Hall and Painted Chamber were re-roofed and furnished for the Commons and Lords respectively for the State Opening of Parliament on 23 February 1835.[6][65][lower-alpha 6] The opening included a statement from the King, read by Lord Brougham, that prorogued parliament until 25 November 1835.[67]

.jpg)

Although the architect Robert Smirke was appointed in December 1834 to design a replacement palace, pressure from the former MP Lieutenant Colonel Sir Edward Cust to open the process up to a competition gained popularity in the press and led to the formation in 1835 of a Royal Commission.[68] This body determined in which style the new construction should be built, and in June they decided that either Elizabethan or gothic styles should be used. The commission also decided that although the original outline of the palace did not have to be used, the surviving buildings of Westminster Hall, the Undercroft Chapel and the Cloisters of St Stephen's should all be incorporated into the new complex.[69]

There were 97 entries to the competition, which closed in November 1835; each entry was to only be identifiable by a pseudonym or symbol.[69] The commission presented their recommendation in February 1836, which was entry 64, identified by a portcullis—the entry of the experienced architect Charles Barry, who won £1,500; Barry's original competition drawings are now lost.[70][71][lower-alpha 7] With no English secular Elizabethan or Gothic buildings to use as inspiration, Barry had visited Belgium to view the town halls for inspiration prior to drafting his design; to complete the necessary pen and ink drawings required, he asked Augustus Pugin, a 23-year-old architect who was, in the words of the art historian Nikolaus Pevsner, "the most fertile and passionate of the Gothicists".[73][74][lower-alpha 8] 34 of the competitors petitioned parliament at the selection of Barry, who was a friend of Cust, but their plea was rejected, and the former prime minister Sir Robert Peel defended Barry and the selection process.[76]

.jpg)

Barry planned what Christopher Jones, the former BBC political editor, called "one long spine of Lords' and Commons' Chambers"[77] which enabled the Speaker of the House of Commons to look through the line of the building to see the Queen's throne in the House of Lords.[78] Between 1836 and 1837 Pugin made more detailed drawings on which estimates were made for the palace's completion;[73] reports of the estimates vary from £707,000[74] to £725,000, with six years until completion of the project.[69][lower-alpha 9]

New Palace of Westminster

The Westminster site covered eight acres, and the palace site partly consisted of unstable, marshy ground. A coffer-dam was built in the river to provide stable foundations for the building; the structure also provided an impressive river frontage. The process of creating the dam started in September 1837. After it was built the water was pumped out and the land allowed to dry; on 1 January 1839 work started on the building.[79] In June 1838 Barry undertook a tour of Britain to locate a supply of British stone for the building. He was accompanied by Dr William Smith, the founder of the science of geology; Sir Walter de la Beche of the Ordnance Geological Survey; and Charles Harriottt Smith, the master mason who had carved the pillars of the National Gallery. They eventually settled on Magnesian Limestone from the Anston quarry of the Duke of Leeds.[80] The stone was badly quarried and handled, and with the polluted atmosphere in London, it has proved to be problematic, with the first signs of deterioration present in 1849, and extensive renovations required periodically.[81][82]

The work to build parliament was contracted to Grissell and Peto, a civil engineering company that had gained its experience building railways. Barry's wife laid the foundation stone on 27 April 1840,[83] in a building that consisted of 11 courtyards with accommodation for 200 people,[79] with 1,180 rooms, 126 staircases, 2 miles of corridors, 15 miles of stem pipes with 1,200 stop cocks.[83] In September 1844 Barry invited Pugin to assist with the design of the fittings for the House of Lords. Pugin subsequently produced numerous designs for a range of items, including the stained glass, produced by Hardman & Co.; the wallpaper and textiles, made by J.G. Crace; and the tiles, manufactured by Mintons.[73][75] Although the two men worked together amicably and effectively, after their deaths their sons publicly argued over which of their fathers deserved the greater credit for the building.[74] In Pevsner's view, "[t]he secret of the undoubted architectural success of the Houses of Parliament lies in this collaboration of two utterly different men and in the union of two utterly different views", Barry's belief in symmetry in design, and Pugin's preference for functional asymmetry.[84]

Although there was a setback in progress with a stonemasons strike between September 1841 and May 1843,[85] the House of Lords had its first sitting in the new chamber in 1847.[86] In December 1851 the House of Commons was opened for a trial period. Complaints from MPs over the acoustics forced Barry to lower the roof, which changed the character of his design so much he refused to enter the chamber again.[74][87] In 1852 the Commons was finished and both Houses sat in their new chambers for the first time, and Queen Victoria first used the newly completed Royal Entrance. The same year Barry was appointed a Knight Bachelor,[86][87] while Pugin suffered a mental breakdown and spent six months in Bethlehem Pauper Hospital for the Insane; he left the hospital shortly before dying in September.[75]

The towers at each end of the western elevation of the building—the clock tower[lower-alpha 10] at the northern end and the Victoria Tower at the southern end—were problematic for Barry, and the plans required ongoing revisions.[89] It took until 1858 to complete the clock tower, and 1860 to finish the Victoria Tower,[86] although Barry's death in May that year was before the building work was completed.[90] The final stages of the work were overseen by Barry's son, Edward, who continued working on the building until 1870.[91] The final cost of the building came to around £2.5 million.[92][lower-alpha 11]

Legacy

The fire became "single most depicted event in nineteenth-century London ... attracting to the scene a host of engravers, watercolourists and painters".[93] Among them were J.M.W. Turner, the landscape painter, who later produced two pictures of the fire, and the Romantic painter John Constable, who sketched the fire from a hansom cab on Westminster Bridge.[93][94]

In 1836 the Royal Commission on Public Records was formed to look into the loss of the parliamentary records, and make recommendations on the preservation of future archives. Their published recommendations in 1837 led to the Public Record Act (1838), which set up the Public Record Office, initially based in Chancery Lane; the body, now based in Kew, has since been renamed as The National Archives.[21][95]

The destruction of the standard measurements led to an overhaul of the British weights and measures system. An inquiry that ran from 1838 to 1841 considered the two competing systems used in the country, the avoirdupois and troy measures, and decided that avoirdupois would be used forthwith; troy weights were retained solely for gold, silver and precious stones.[96] The destroyed weights and measures were recast by William Simms, the scientific instrument maker, who produced the replacements after "countless hours of tests and experiments to determine the best metal, the best shape of bar, and the corrections for temperature".[96][97]

Although Dickens deplored the cost of re-building parliament, Westminster Palace has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1987, and is classified as being of outstanding universal value. UNESCO describe the site as being "of great historic and symbolic significance", in part because the it is "one of the most significant monuments of neo-Gothic architecture, as an outstanding, coherent and complete example of neo-Gothic style"; the organisation also consider the building to have an "iconic silhouette ... [which is] an intrinsic part of its identity, which is recognised internationally".[98] The decision to use the Gothic design for the palace set the national style, even for secular buildings,[99] which also "drew attention to the close bond between Church and State at Westminster"[100]

In 2015 the chairman of the House of Commons Commission, John Thurso, stated that the palace was in a "dire condition". The Speaker of the House of Commons, John Bercow, agreed and said that the building is in need of extensive repairs. He reported that parliament "suffers from flooding, contains a great deal of asbestos and has fire safety issues", which would cost £3 billion to fix.[101]

Notes and references

Notes

- ↑ In 1707, following the Acts of Union which led to 45 Scottish MPs joining the House of Commons, Wren also widened the galleries in the chamber.[8]

- ↑ Dickens later mocked the decision, commenting that "[t]he sticks were housed in Westminster, and it would naturally occur to any intelligent person that nothing could be easier than to allow them to be carried away for fire-wood by the miserable people who lived in that neighbourhood. However, they never had been useful, and official routine required that they should never be, and so the order went out that they were to be privately and confidentially burnt."[23]

- ↑ In July that year parliament had passed the Chimney Sweeps Act, which stopped children under ten from working as sweeps, and making it a criminal offence for anyone to force anyone from entering a flue.[30]

- ↑ A flashover fire is one that occurs in a confined space where the heat in that spaces rises quickly enough for the objects in the room to reach their combustible temperature at the same time. Those objects will give off ignitable vapours and gasses as they catch fire, and these will simultaneously ignite and expand, creating an fireball. The temperatures reached are between 500–600 °C (about 900–1100 °F).[34]

- ↑ Braidwood had transferred to London from the Edinburgh Fire Brigade the year before; the Edinburgh service was the first municipal fire service in Britain.[33]

- ↑ The Painted Chamber was used by the House of Lords until 1847; it was demolished in 1851.[6] The Lesser Hall was used as the chamber for the House of Commons until 1852.[66]

- ↑ £1,500 in 1836 equates to approximately £123,000 in 2015, according to calculations based on Consumer Price Index measure of inflation.[72]

- ↑ In addition to undertaking Barry's drawings, Pugin also undertook the draughting for another entrant, James Gillespie Graham, the Scottish architect.[75]

- ↑ £707,000 in 1837 equates to approximately £56 million in 2015, while £725,000 equates to approximately £57,500,000, according to calculations based on Consumer Price Index measure of inflation.[72]

- ↑ In 2012, to celebrate the Diamond Jubilee of Elizabeth II, the clock tower was renamed the Elizabeth Tower.[88]

- ↑ £2.5 million in 1870 equates to approximately £209 million in 2015, according to calculations based on Consumer Price Index measure of inflation.[72]

References

- ↑ "Henry III and the Palace". UK Parliament. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

- ↑ Jones 1983, p. 10.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "A Brief Chronology of the House of Commons" (PDF). UK Parliament. August 2010. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- ↑ Jones 1983, pp. 15–16.

- ↑ "Location of Parliaments in the later middle ages". UK Parliament. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Shenton, Caroline. "The Fire of 1834 and the Old Palace of Westminster" (PDF). Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- ↑ Walker 1974, pp. 98–99.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "The Commons Chamber in the 17th and 18th centuries". UK Parliament. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ↑ Shenton 2012, p. 16.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Bryant 2014, p. 43.

- ↑ Shenton 2012, p. 18.

- ↑ Flanders 2012, p. 330.

- ↑ "Destruction by fire, 1834". UK Parliament. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- ↑ Shenton 2012, p. 56.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Goetzmann & Rouwenhorst 2005, p. 111.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 "Tally Sticks". UK Parliament. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- ↑ Baxter 2014, pp. 197–98.

- ↑ Baxter 2014, p. 233.

- ↑ Baxter 2014, p. 355.

- ↑ Dickens 1937, p. 175.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 21.6 21.7 21.8 Shenton, Caroline (16 October 2013). "The day Parliament burned down". UK Parliament. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- ↑ Jones 1983, p. 63.

- ↑ Dickens 1937, pp. 175–76.

- ↑ Shenton 2012, p. 41.

- ↑ Shenton 2012, pp. 22–23.

- ↑ Shenton 2012, p. 50.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Jones 1983, p. 73.

- ↑ Shenton 2012, p. 68.

- ↑ Shenton 2012, pp. 62–63.

- ↑ Shenton 2012, p. 63.

- ↑ Shenton 2012, pp. 64–66.

- ↑ Shenton 2012, p. 60.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 Withington 2003, p. 76.

- ↑ DiMaio & DiMaio 2001, pp. 386–87.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 "Awful destruction by fire of houses of parliament". The Manchester Guardian (Manchester). 18 October 1834.

- ↑ Shenton 2012, p. 75.

- ↑ Shenton 2012, p. 77.

- ↑ Shenton 2012, p. 81.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 Flanders 2012, p. 331.

- ↑ Shenton 2012, p. 104.

- ↑ "Destruction of Both Houses of Parliament by Fire". The Times (London). 17 October 1834. p. 3.

- ↑ Jones 1983, p. 66.

- ↑ Shenton 2012, p. 89.

- ↑ Blackstone 1957, pp. 118–19.

- ↑ Carlyle 1888, p. 227.

- ↑ Broughton 1911, p. 22.

- ↑ Jones 1983, p. 67.

- ↑ Shenton 2012, pp. 128—29, 195.

- ↑ Shenton 2012, pp. 197–98.

- ↑ Shenton 2012, p. 203.

- ↑ Shenton 2012, pp. 205–06.

- ↑ Shenton 2012, p. 217.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 53.2 "Destruction of Both Houses of Parliament by Fire". The Times (London). 18 October 1834. p. 5.

- ↑ Flanders 2012, p. 104.

- ↑ Gupta 2009, p. 37.

- ↑ Shenton 2012, p. 191.

- ↑ Jones 2012, p. 36.

- ↑ Shenton 2012, p. 4.

- ↑ Jones 1983, p. 71.

- ↑ Shenton 2012, pp. 243–44.

- ↑ Shenton 2012, pp. 237–38.

- ↑ "Destruction of the Houses of Parliament: Report of the Privy Council". The Observer. 16 November 1834. p. 2.

- ↑ "Place of Assembly for the Two Houses Provided by the King". The Observer. 19 October 1834. p. 2.

- ↑ Bryant 2014, p. 44.

- ↑ Bryant 2014, pp. 43—44.

- ↑ "The Commons Chamber in the 17th and 18th centuries". UK Parliament. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ↑ Shenton 2012, pp. 241–42.

- ↑ Rorabaugh 1973, pp. 160, 162–63, 165.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 69.2 "Rebuilding the Palace". UK Parliament. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- ↑ Walker 1974, p. 104.

- ↑ "London, Sunday, February 7". The Observer. 8 February 1836. p. 2.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 72.2 UK CPI inflation numbers based on data available from Gregory Clark (2014), "What Were the British Earnings and Prices Then? (New Series)" MeasuringWorth.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 73.2 Bradley & Pevsner 2003, p. 215.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 74.2 74.3 Port 2004.

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 75.2 Wedgwood 2004.

- ↑ Jones 1983, p. 79.

- ↑ Jones 1983, p. 80.

- ↑ Quinault 1992, p. 84.

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 Jones 1983, p. 97.

- ↑ Jones 1983, pp. 100–01.

- ↑ Bradley & Pevsner 2003, p. 218.

- ↑ "The stonework". UK Parliament. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 Jones 1983, p. 101.

- ↑ Bradley & Pevsner 2003, pp. 215–16.

- ↑ Jones 1983, pp. 101–02.

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 86.2 Bradley & Pevsner 2003, p. 216.

- ↑ 87.0 87.1 Jones 1983, p. 107.

- ↑ "Elizabeth Tower naming ceremony". UK Parliament. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ↑ Jones 1983, p. 108.

- ↑ Jones 1983, p. 113.

- ↑ Jones 1983, p. 116.

- ↑ Quinault 1992, p. 91.

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 Galinou & Hayes 1996, p. 179.

- ↑ Shenton 2012, pp. 113–14.

- ↑ Shenton 2012, pp. 256–57.

- ↑ 96.0 96.1 Shenton 2012, p. 258.

- ↑ McConnell 2004.

- ↑ "Palace of Westminster and Westminster Abbey including Saint Margaret's Church". UNESCO. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ↑ Bradley & Pevsner 2003, p. 214.

- ↑ Quinault 1992, p. 103.

- ↑ "Speaker John Bercow warns over Parliament repairs". BBC. 3 March 2015.

Sources

- Baxter, William T. (2014). Accounting Theory. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-63177-3.

- Blackstone, G.V. (1957). A History of the British Fire Service. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. OCLC 1701338.

- Bradley, Simon; Pevsner, Nikolaus (2003). London 6: Westminster. New Haven, CT and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09595-1.

- Broughton, Lord (1911). Recollections of a Long Life, Volume 5. London: J. Murray. OCLC 1343383.

- Bryant, Chris (2014). Parliament: The Biography (Volume II – Reform). London: Transworld. ISBN 978-0-8575-2224-5.

- Carlyle, Thomas (1888). Letters. 1826–1836. London: Macmillan. OCLC 489764019.

- Dickens, Charles (1937). The Speeches of Charles Dickens. London: Michael Joseph.

- DiMaio, Dominick; DiMaio, Vincent (2001). Forensic Pathology (Second ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-4241-2.

- Flanders, Judith (2012). The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London. London: Atlantic Books. ISBN 978-0-8578-9881-4.

- Galinou, Mireille; Hayes, John (1996). London in Paint: Oil Paintings in the Collection at the Museum of London. London: Museum of London. ISBN 978-0-904818-51-2.

- Goetzmann, William N.; Rouwenhorst, K. Geert (2005). The Origins of Value: The Financial Innovations that Created Modern Capital Markets. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517571-4.

- Gupta, SV (2009). Units of Measurement: Past, Present and Future. International System of Units. Heidelburg: Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-642-00738-5.

- Jones, Christopher (1983). The Great Palace. London: BBC Books. ISBN 978-0-5632-0178-6.

- Jones, Clyve (2012). A Short History of Parliament: England, Great Britain, the United Kingdom, Ireland and Scotland. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-8438-3717-6.

- McConnell, Anita (2004). "Simms, William (1793–1860)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press). doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/25568. Retrieved 27 April 2015. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Port, MH (2004). "Barry, Sir Charles (1795–1860)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press). doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/1550. Retrieved 10 April 2015. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Quinault, Roland (1992). "Westminster and the Victorian Constitution". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press) 2: 79–104. JSTOR 3679100.

- Rorabaugh, W. J. (December 1973). "Politics and the Architectural Competition for the Houses of Parliament, 1834–1837". Victorian Studies 17 (2): 155–175. JSTOR 3826182.

- Shenton, Caroline (2012). The Day Parliament Burned Down. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-964670-8.

- Walker, R.J.B. (1974). "The Palace of Westminster After the Fire of 1834". The Volume of the Walpole Society (1972–1974) 44: 94–122. JSTOR 41829434.

- Wedgwood, Alexandra (2004). "Pugin, Augustus Welby Northmore (1812–1852)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press). doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/22869. Retrieved 10 April 2015. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Withington, John (2003). The Disastrous History of London. Stroud, Glos: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7509-3321-6.

Coordinates: 51°29′57.5″N 00°07′29.1″W / 51.499306°N 0.124750°W