Bulgaria

Coordinates: 42°45′N 25°30′E / 42.750°N 25.500°E

| Republic of Bulgaria |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

Motto:

|

||||||

| Anthem: Мила Родино (Bulgarian) Mila Rodino (transliteration) Dear Motherland |

||||||

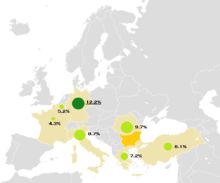

![Location of Bulgaria (dark green)– in Europe (green & dark grey)– in the European Union (green) – [Legend]](../I/m/EU-Bulgaria.svg.png) Location of Bulgaria (dark green) – in Europe (green & dark grey) |

||||||

| Capital and largest city | Sofia 42°41′N 23°19′E / 42.683°N 23.317°E | |||||

| Official languages | Bulgarian | |||||

| Official script | Cyrillic | |||||

| Ethnic groups (2011[1]) |

|

|||||

| Demonym | Bulgarian | |||||

| Government | Unitary parliamentary republic | |||||

| - | President | Rosen Plevneliev | ||||

| - | Prime Minister | Boyko Borisov | ||||

| Legislature | National Assembly | |||||

| Formation | ||||||

| - | Medieval states: | |||||

| - | First Bulgarian Empire | 681-1018 | ||||

| - | Second Bulgarian Empire | 1185-1396 | ||||

| - | Modern state: | |||||

| - | Principality of Bulgaria | 3 March 1878[note 1] | ||||

| - | Independence from the Ottoman Empire | 5 October 1908[note 2] | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| - | Total | 110,994 km2 (105th) 42,823 sq mi |

||||

| - | Water (%) | 0.3 | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| - | 2011 census | 7,364,570[2] (98th) | ||||

| - | Density | 66.2/km2 (139th) 171/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2015 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $128.053 billion[3] (66th) | ||||

| - | Per capita | $17,869[3] (67th) | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2015 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $57.596 billion[3] (75th) | ||||

| - | Per capita | $8,037[3] (76th) | ||||

| Gini (2013) | medium |

|||||

| HDI (2013) | high · 58th |

|||||

| Currency | Lev (BGN) | |||||

| Time zone | EET (UTC+2) | |||||

| - | Summer (DST) | EEST (UTC+3) | ||||

| Drives on the | right | |||||

| Calling code | +359 | |||||

| ISO 3166 code | BG | |||||

| Internet TLD | .bg | |||||

Bulgaria ![]() i/bʌlˈɡɛəriə/, /bʊlˈ.../ (Bulgarian: България, IPA: [bɐɫˈɡarijɐ]), officially the Republic of Bulgaria (Bulgarian: Република България, IPA: [rɛˈpublikɐ bɐɫˈɡarijɐ]), is a country in southeastern Europe. It is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and Macedonia to the west, Greece and Turkey to the south, and the Black Sea to the east. With a territory of 110,994 square kilometres (42,855 sq mi), Bulgaria is Europe's 16th-largest country.

i/bʌlˈɡɛəriə/, /bʊlˈ.../ (Bulgarian: България, IPA: [bɐɫˈɡarijɐ]), officially the Republic of Bulgaria (Bulgarian: Република България, IPA: [rɛˈpublikɐ bɐɫˈɡarijɐ]), is a country in southeastern Europe. It is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and Macedonia to the west, Greece and Turkey to the south, and the Black Sea to the east. With a territory of 110,994 square kilometres (42,855 sq mi), Bulgaria is Europe's 16th-largest country.

Organised prehistoric cultures began developing on Bulgarian lands during the Neolithic period. Its ancient history saw the presence of the Thracians and later the Greeks and Romans. The emergence of a unified Bulgarian state dates back to the establishment of the First Bulgarian Empire in 681 AD, which dominated most of the Balkans and functioned as a cultural hub for Slavs during the Middle Ages. With the downfall of the Second Bulgarian Empire in 1396, its territories came under Ottoman rule for nearly five centuries. The Russo-Turkish War (1877–78) led to the formation of the Third Bulgarian State. The following years saw several conflicts with its neighbours, which prompted Bulgaria to align with Germany in both world wars. In 1946 it became a single-party socialist state as part of the Soviet-led Eastern Bloc. In December 1989 the ruling Communist Party allowed multi-party elections, which subsequently led to Bulgaria's transition into a democracy and a market-based economy.

Bulgaria's population of 7.4 million people is predominantly urbanised and mainly concentrated in the administrative centres of its 28 provinces. Most commercial and cultural activities are centred on the capital and largest city, Sofia. The strongest sectors of the economy are heavy industry, power engineering, and agriculture, all of which rely on local natural resources.

The country's current political structure dates to the adoption of a democratic constitution in 1991. Bulgaria is a unitary parliamentary republic with a high degree of political, administrative, and economic centralisation. It is a member of the European Union, NATO, and the Council of Europe; a founding state of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE); and has taken a seat at the UN Security Council three times.

History

Prehistory and antiquity

Human activity in the lands of modern Bulgaria can be traced back to the Paleolithic. Animal bones incised with man-made markings from Kozarnika cave are assumed to be the earliest examples of symbolic behaviour in humans.[6] Organised prehistoric societies in Bulgarian lands include the Neolithic Hamangia culture,[7] Vinča culture[8] and the eneolithic Varna culture (fifth millennium BC). The latter is credited with inventing gold working and exploitation.[9][10] Some of these first gold smelters produced the coins, weapons and jewellery of the Varna Necropolis treasure, the oldest in the world with an approximate age of over 6,000 years.[11] This site also offers insights for understanding the social hierarchy of the earliest European societies.[12][13]

Thracians, one of the three primary ancestral groups of modern Bulgarians,[14] began appearing in the region during the Iron Age.[15] Most of their numerous tribes were united in the Odrysian kingdom around 500 BC by king Teres,[16][17] but they were eventually subjugated by Alexander the Great and later by the Romans in 46 AD. After the division of the Roman Empire in 5th century the area fell under Byzantine control. By this time, Christianity had already spread in the area. A small Gothic community in Nicopolis ad Istrum produced the first Germanic language book in the 4th century, the Wulfila Bible.[18][19] The first Christian monastery in Europe was established around the same time by Saint Athanasius in central Bulgaria.[20] From the 6th century the easternmost South Slavs gradually settled in the region, assimilating the Hellenised or Romanised Thracians.[21][22]

First Bulgarian Empire

In 680 Bulgar tribes,[14] under the leadership of Asparukh moved south across the Danube and settled in the area between the lower Danube and the Balkan, establishing their capital at Pliska.[23][24] A peace treaty with Byzantium in 681 marked the beginning of the First Bulgarian Empire. The Bulgars gradually mixed up with the local population, adopting a common language on the basis of the local Slavic dialect.[25]

Succeeding rulers strengthened the Bulgarian state throughout the 8th and 9th centuries. Krum doubled the country's territory, killed Byzantine emperor Nicephorus I in the Battle of Pliska,[26] and introduced the first written code of law. Paganism was abolished in favour of Eastern Orthodox Christianity under Boris I in 864. This conversion was followed by a Byzantine recognition of the Bulgarian church[27] and the adoption of the Cyrillic alphabet developed at Preslav[28] which strengthened central authority and helped fuse the Slavs and Bulgars into a unified people.[29][30] A subsequent cultural golden age began during the 34-year rule of Simeon the Great, who also achieved the largest territorial expansion of the state.[31]

Wars with Magyars and Pechenegs and the spread of the Bogomil heresy weakened Bulgaria after Simeon's death.[32][33] Consecutive Rus' and Byzantine invasions resulted in the seizure of the capital Preslav by the Byzantine army in 971.[34] Under Samuil, Bulgaria briefly recovered from these attacks,[35] but this rise ended when Byzantine emperor Basil II defeated the Bulgarian army at Klyuch in 1014. Samuil died shortly after the battle,[36] and by 1018 the Byzantines had ended the First Bulgarian Empire.[37]

Second Bulgarian Empire

After his conquest of Bulgaria, Basil II prevented revolts and discontent by retaining the rule of the local nobility and by relieving the newly conquered lands of the obligation to pay taxes in gold, allowing them to be paid in kind instead.[38] He also allowed the Bulgarian Patriarchate to retain its autocephalous status and all its dioceses, but reduced it to an archbishopric.[38][39] After his death Byzantine domestic policies changed and a series of unsuccessful rebellions broke out, the largest being led by Peter Delyan. In 1185 Asen dynasty nobles Ivan Asen I and Peter IV organised a major uprising which resulted in the re-establishment of the Bulgarian state. Ivan Asen and Peter laid the foundations of the Second Bulgarian Empire with Tarnovo as a capital.[40]

_E3.jpg)

Kaloyan, the third of the Asen monarchs, extended his dominion to Belgrade and Ohrid. He acknowledged the spiritual supremacy of the Pope and received a royal crown from a papal legate.[41] The empire reached its zenith under Ivan Asen II (1218–1241), when commerce and culture flourished.[41] The strong economic and religious influence of Tarnovo made it a "Third Rome", unlike the already declining Constantinople.[42]

The country's military and economic might declined after the Asen dynasty ended in 1257, facing internal conflicts, constant Byzantine and Hungarian attacks and Mongol domination.[41][43] By the end of the 14th century, factional divisions between the feudal landlords and the spread of Bogomilism had caused the Second Bulgarian Empire to split into three tsardoms—Vidin, Tarnovo and Karvuna—and several semi-independent principalities that fought each other, along with Byzantines, Hungarians, Serbs, Venetians and Genoese. By the late 14th century the Ottoman Turks had started their conquest of Bulgaria and had taken most towns and fortresses south of the Balkan mountains.[41]

Ottoman rule

Tarnovo was captured by the Ottomans after a three-month siege in 1393. After the Battle of Nicopolis in 1396 brought about the fall of the Vidin Tsardom, the Ottomans conquered all Bulgarian lands south of the Danube. The nobility was eliminated and the peasantry was enserfed to Ottoman masters,[44] with much of the educated clergy fleeing to other countries.[45] Under the Ottoman system, Christians were considered an inferior class of people. Thus, Bulgarians, like other Christians, were subjected to heavy taxes and a small portion of the Bulgarian populace experienced partial or complete Islamisation,[46] and their culture was suppressed.[45] Ottoman authorities established the Rum Millet, a religious administrative community which governed all Orthodox Christians regardless of their ethnicity.[47] Most of the local population gradually lost its distinct national consciousness, identifying as Christians.[48][49] However, the clergy remaining in some isolated monasteries kept it alive, and that helped it to survive as in some rural, remote areas,[50] as well as in the militant Catholic community in the northwestern part of the country.[51]

Several Bulgarian revolts erupted throughout the nearly five centuries of Ottoman rule, most notably the Habsburg-backed[52] Tarnovo uprisings in 1598 and in 1686, the Chiprovtsi Uprising in 1688 and Karposh's Rebellion in 1689.[44] In the 18th century, the Enlightenment in Western Europe provided influence for the initiation of a movement known as the National awakening of Bulgaria.[44] It restored national consciousness and became a key factor in the liberation struggle, resulting in the 1876 April Uprising. Up to 30,000 Bulgarians were killed as Ottoman authorities put down the rebellion. The massacres prompted the Great Powers to take action.[53] They convened the Constantinople Conference in 1876, but their decisions were rejected by the Ottomans. This allowed the Russian Empire to seek a solution by force without risking military confrontation with other Great Powers, as had happened in the Crimean War.[53] In 1877 Russia declared war on the Ottoman Empire and defeated its forces with the help of Bulgarian volunteers.

Third Bulgarian state

The Treaty of San Stefano was signed on 3 March 1878 by Russia and the Ottoman Empire, and included a provision to set up an autonomous Bulgarian principality roughly on the territories of the Second Bulgarian Empire.[55][56] The other Great Powers immediately rejected the treaty out of fear that such a large country in the Balkans might threaten their interests. It was superseded by the subsequent Treaty of Berlin, signed on 13 July, provided for a much smaller state comprising Moesia and the region of Sofia, leaving large populations of Bulgarians outside the new country.[55][57] This played a significant role in forming Bulgaria's militaristic approach to foreign affairs during the first half of the 20th century.[58]

The Bulgarian principality won a war against Serbia and incorporated the semi-autonomous Ottoman territory of Eastern Rumelia in 1885, proclaiming itself an independent state on 5 October 1908.[59] In the years following independence, Bulgaria increasingly militarised and was often referred to as "the Balkan Prussia".[60][61]

.jpg)

Between 1912 and 1918, Bulgaria became involved in three consecutive conflicts—two Balkan Wars and World War I. After a disastrous defeat in the Second Balkan War, Bulgaria again found itself fighting on the losing side as a result of its alliance with the Central Powers in World War I. Despite fielding more than a quarter of its population in a 1,200,000-strong army[62][63] and achieving several decisive victories at Doiran and Dobrich, the country capitulated in 1918. The war resulted in significant territorial losses, and a total of 87,500 soldiers killed.[64] More than 253,000 refugees immigrated to Bulgaria from 1912 to 1929 due to the effects of these wars,[65] placing additional strain on the already ruined national economy.[66]

The political unrest resulting from these losses led to the establishment of a royal authoritarian dictatorship by tsar Boris III (1918–1943). Bulgaria entered World War II in 1941 as a member of the Axis but declined to participate in Operation Barbarossa and saved its Jewish population from deportation to concentration camps.[67] The sudden death of Boris III in the summer of 1943 pushed the country into political turmoil as the war turned against Germany and the Communist guerrilla movement gained momentum. The government of Bogdan Filov subsequently failed to achieve peace with the Allies. Bulgaria did not comply with Soviet demands to expel German forces from its territory, resulting in a declaration of war and an invasion by the USSR in September 1944.[68] The Communist-dominated Fatherland Front took power, ended participation in the Axis and joined the Allied side until the war ended.[69]

The left-wing uprising of 9 September 1944 led to the abolition of monarchic rule, but it was not until 1946 that a single-party people's republic was established.[70] It became a part of the Soviet sphere of influence under the leadership of Georgi Dimitrov (1946–1949), who laid the foundations for a rapidly industrialising stalinist state which was also highly repressive with thousands of dissidents executed.[71][72][73] By the mid-1950s standards of living rose significantly,[74] while political repressions were lessened.[75] By the 1980s both national and per capita GDP quadrupled,[76] but the economy remained prone to debt spikes, the most severe taking place in 1960, 1977 and 1980.[77] The Soviet-style planned economy saw some market-oriented policies emerging on an experimental level under Todor Zhivkov (1954–1989).[78] His daughter Lyudmila bolstered national pride by promoting Bulgarian heritage, culture and arts worldwide.[79] In an attempt to erase the identity of the ethnic Turk minority, an assimilation campaign was launched in 1984 which included closing mosques and forcing ethnic Turks to adopt Slavic names. These policies (combined with the end of communist rule in 1989) resulted in the emigration of some 300,000 ethnic Turks to Turkey.[80][81]

Under the influence of the collapsing of the Eastern Bloc, on 10 November 1989 the Communist Party gave up its political monopoly, Zhivkov resigned, and Bulgaria embarked on a transition to a parliamentary democracy.[82] The first free elections in June 1990 were won by the Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP, the freshly renamed Communist Party).[83] A new constitution that provided for a relatively weak elected President and for a Prime Minister accountable to the legislature was adopted in July 1991. The new system initially failed to improve living standards or create economic growth—the average quality of life and economic performance remained lower than under Communism well into the early 2000s.[84] A 1997 reform package restored economic growth, but living standards continued to suffer.[85] After 2001 economic, political and geopolitical conditions improved greatly,[86] and Bulgaria achieved high Human Development status.[87] It became a member of NATO in 2004[88] and participated in the War in Afghanistan. After several years of reforms it joined the European Union in 2007 despite continued concerns about government corruption.[89]

Geography

Bulgaria occupies a portion of the eastern Balkan peninsula, bordering five countries—Greece and Turkey to the south, Macedonia and Serbia to the west, and Romania to the north. The land borders have a total length of 1,808 kilometres (1,123 mi), and the coastline has a length of 354 kilometres (220 mi).[90] Its total area of 110,994 square kilometres (42,855 sq mi) ranks it as the world's 105th-largest country.[91][92] Bulgaria's geographic coordinates are 43° N 25° E.[93]

Right: Maslen nos Primorsko on the Black Sea coast.

The most notable topographical features are the Danubian Plain, the Balkan Mountains, the Thracian Plain, and the Rhodope Mountains.[90] The southern edge of the Danubian Plain slopes upward into the foothills of the Balkans, while the Danube defines the border with Romania. The Thracian Plain is roughly triangular, beginning southeast of Sofia and broadening as it reaches the Black Sea coast.[90]

The Balkan mountains run laterally through the middle of the country. The mountainous southwest of the country has two alpine ranges—Rila and Pirin, which border the lower but more extensive Rhodope Mountains to the east.[90] Bulgaria is home to the highest point of the Balkan peninsula, Musala, at 2,925 metres (9,596 ft)[94] and its lowest point is sea level. Plains occupy about one-third of the territory, while plateaus and hills occupy 41 per cent.[95] The country has a dense network of about 540 rivers, most of which are relatively small and with low water levels.[96] The longest river located solely in Bulgarian territory, the Iskar, has a length of 368 kilometres (229 mi). Other major rivers include the Struma and the Maritsa in the south.[90]

Bulgaria has a dynamic climate, which results from its being positioned at the meeting point of Mediterranean and continental air masses and the barrier effect of its mountains.[90] Northern Bulgaria averages 1 °C (1.8 °F) cooler and registers 200 millimetres (7.9 in) more precipitation annually than the regions south of the Balkan mountains. Temperature amplitudes vary significantly in different areas. The lowest recorded temperature is −38.3 °C (−36.9 °F), while the highest is 45.2 °C (113.4 °F).[97] Precipitation averages about 630 millimetres (24.8 in) per year, and varies from 500 millimetres (19.7 in) in Dobrudja to more than 2,500 millimetres (98.4 in) in the mountains. Continental air masses bring significant amounts of snowfall during winter.[98]

Environment

Bulgaria adopted the Kyoto Protocol[99] and achieved the protocol's objectives by reducing carbon dioxide emissions from 1990 to 2009 by 30 percent.[100] However, pollution from factories and metallurgy works and severe deforestation continue to cause major problems to the health and welfare of the population.[101] In 2013, air pollution in Bulgaria was more severe than any other European country.[102] Urban areas are particularly affected by energy production from coal-based powerplants and automobile traffic,[103][104] while pesticide usage in the agriculture and antiquated industrial sewage systems produce extensive soil and water pollution with chemicals and detergents.[105] Bulgaria is the only EU member which does not recycle municipal waste,[106] although an electronic waste recycling plant opened in June 2010.[107] The situation has improved in recent years, and several government-funded programmes have been put into place in an attempt to reduce pollution levels.[105] According to Yale University's 2012 Environmental Performance Index, Bulgaria is a "modest performer" in protecting the environment.[108] In November 2014 the Maritsa Iztok-2 lignite fired power station was ranked as the industrial facility that is causing the highest damage costs to health and the environment in Bulgaria and the entire European Union by the European Environment Agency.[109]

Surface waters in Bulgaria as a whole are in good condition. Over 75% of the length of rivers in the country meet the standards for good quality. The improvement of water quality started 1998 - there is a clear trend of sustainability and slight improvement of all indicators for water quality between 1998 and 2007.[110]

Biodiversity

The interaction of climatic, hydrological, geological and topographical conditions have produced a relatively wide variety of plant and animal species.[112] Bulgaria's biodiversity is conserved in three national parks, 11 nature parks[113] and 17 biosphere reserves.[114] Nearly 35 per cent of its land area consists of forests,[115] where some of the oldest trees in the world, such as Baikushev's pine and the Granit oak,[116] grow. Most of the plant and animal life is central European, although representatives of Arctic and alpine species are present at high altitudes.[117] Its flora encompass more than 3,800 species of which 170 are endemic and 150 are considered endangered.[118] A checklist of larger fungi of Bulgaria reported that more than 1,500 species occur in the country.[119] Animal species include owls, rock partridges, wallcreepers[117] and brown bears.[120] The Eurasian lynx and the eastern imperial eagle have small, but growing populations.[121]

In 1998, the Bulgarian government approved the National Biological Diversity Conservation Strategy, a comprehensive programme seeking the preservation of local ecosystems, protection of endangered species and conservation of genetic resources.[122] Bulgaria has some of the largest Natura 2000 areas in Europe covering 33.8% of its territory.[123]

Politics

Bulgaria is a parliamentary democracy in which the most powerful executive position is that of prime minister.[86] The political system has three branches—legislative, executive and judicial, with universal suffrage for citizens at least 18 years old. The Constitution of Bulgaria provides also possibilities of direct democracy.[124] Elections are supervised by an independent Central Election Commission that includes members from all major political parties. Parties must register with the commission prior to participating in a national election.[125] Normally, the prime minister-elect is the leader of the party receiving the most votes in parliamentary elections, although this is not always the case.[86]

Political parties gather in the National Assembly, which consists of 240 deputies elected to four-year terms by direct popular vote. The National Assembly has the power to enact laws, approve the budget, schedule presidential elections, select and dismiss the Prime Minister and other ministers, declare war, deploy troops abroad, and ratify international treaties and agreements. The president serves as the head of state and commander-in-chief of the armed forces, and has the authority to return a bill for further debate, although the parliament can override the presidential veto by a simple majority vote of all members of parliament.[86]

GERB-backed Rosen Plevneliev is the elected President of Bulgaria after the presidential elections in 2011 in which he received 52.5 per cent of the votes on the second round against 47.5 per cent for his Socialist Party opponent Ivaylo Kalfin.[126]

Until February 2013 GERB had 117 seats in the National Assembly, ruling as a minority government without support from the other political parties in the parliament.[127] The government resigned on 20 February 2013 after nationwide protests caused by high costs of utilities, low living standards[128] and the failure of the democratic system.[129] The protest wave was marked by self-immolations, spontaneous demonstrations and a strong sentiment against political parties.[130] As a consequence, the Parliament was dissolved and a new provisional government was set up by the President.

The subsequent snap elections in May 2013 elections resulted in a narrow GERB win.[131] However, with no support from the other three political parties that entered the parliament, on 24 May, GERB leader Borisov returned the president's mandate to try and form a government. The Bulgarian Socialist Party nominated ex-Finance Minister Plamen Oresharski for the post of Prime Minister.[132] He was appointed on 29 May 2013.[133]

Only two weeks after its initial formation the Oresharski government came under criticism and had to deal with country-wide protests by the citizens, with those in Sofia reaching up to 11 000 participants.[134] One of the main reasons for these protests was the controversial appointment of media mogul Delyan Peevski as a chief of the National Security State Agency.[135] The protests continued over the lifetime of the Oresharski government. In all, the government survived 5 votes of no-confidence before voluntarily resigning.[136] Following an agreement from the three largest parties (GERB, BSP and DPS) to hold early parliamentary elections for 5 October 2014,[137] the cabinet agreed to resign by the end of July,[138] with the resignation of the cabinet becoming a fact on 23 July 2014.[139] The next day parliament voted 180-8 (8 abstained and 44 were absent) to accept the government's resignation.[140] Following the vote, President Plevneliev offered the mandate to GERB to try and form government, but it was refused.[141] The next day the BSP returned the mandate as well.[142] On 30 July, the DPS refused the mandate as well.[143] Finally, on 6 August, a caretaker government led by Georgi Bliznashki was sworn into office and the Oresharski government was officially dissolved.

.svg.png)

GERB (centre-right, 84)

BSP Left Bulgaria (centre-left, 39)

DPS (centrist, 36)

Reformist Bloc (right-wing, 23)

Patriotic Front (right-wing, 18)

BBTs (populist, 14)

Attack (far right, 11)

ABV (centre-left, 11)

Independent (4)

As agreed, parliamentary elections were held on 5 October 2014 to elect the 43rd National Assembly.[145] GERB remained the largest party, winning 84 of the 240 seats with around a third of the vote. A total of eight parties won seats, the first time since the beginning of democratic elections in 1990 that more than seven parties entered parliament.[146] After being tasked by President Rosen Plevneliev to form a government, Borisov's GERB formed a coalition with the Reformist Bloc,[147][148][149] had a partnership agreement for the support of the Alternative for Bulgarian Revival,[150] and also had the outside support of the Patriotic Front. The cabinet of twenty ministers was approved by a majority of 136-97 (with one abstention).[151] Borisov was then chosen as prime minister by an even larger vote of 149-85.[152] Borisov become the first person to be elected twice as Prime Minister in the recent history of Bulgaria. With the support of the coalition partner (the Reformist Bloc) members of the parties in the Bloc (Democrats for a Strong Bulgaria (DSB), Union of Democratic Forces (SDS), Bulgaria for Citizens Movement (DBG) and Bulgarian Agrarian National Union (BZNS)) were chosen for Minister positions. The vice chairman of the Alternative for Bulgarian Revival party Ivaylo Kalfin was voted for Depute Prime Minister and Minister of Labor and Social Policy.

Bulgaria has a typical civil law legal system.[153] The judiciary is overseen by the Ministry of Justice. The Supreme Administrative Court and Supreme Court of Cassation are the highest courts of appeal and oversee the application of laws in subordinate courts.[125] The Supreme Judicial Council manages the system and appoints judges. Bulgaria's judiciary, along with other institutions, remains one of Europe's most corrupt and inefficient.[154][155][156][157]

Law enforcement is carried out by organisations mainly subordinate to the Ministry of the Interior.[158] The National Police Service (NPS) combats general crime, maintains public order and supports the operations of other law enforcement agencies.[159] NPS fields 27,000 police officers in its local and national sections.[160] The Ministry of Interior also heads the Border Police Service and the National Gendarmerie—a specialised branch for anti-terrorist activity, crisis management and riot control. Counterintelligence and national security are the responsibility of the State Agency for National Security, established in 2008.[161]

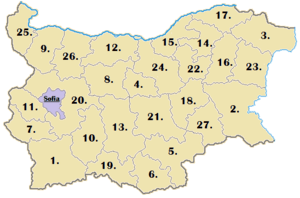

Administrative divisions

Bulgaria is a unitary state.[162] Since the 1880s, the number of territorial management units has varied from seven to 26.[163] Between 1987 and 1999 the administrative structure consisted of nine provinces (oblasti, singular oblast). A new administrative structure was adopted in parallel with the decentralisation of the economic system.[164] It includes 27 provinces and a metropolitan capital province (Sofia-Grad). All areas take their names from their respective capital cities. The provinces subdivide into 264 municipalities.

Municipalities are run by mayors, who are elected to four-year terms, and by directly elected municipal councils. Bulgaria is a highly centralised state, where the national Council of Ministers directly appoints regional governors and all provinces and municipalities are heavily dependent on it for funding.[125]

|

Foreign relations and the military

Bulgaria became a member of the United Nations in 1955 and since 1966 has been a non-permanent member of the Security Council three times, most recently from 2002 to 2003.[165] Bulgaria was also among the founding nations of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) in 1975. It joined NATO on 29 March 2004, signed the European Union Treaty of Accession on 25 April 2005,[88][166] and became a full member of the European Union on 1 January 2007.[89] Polls carried out seven years after the country's accession to the EU found only 15% of Bulgarians felt they had personally benefited from membership, with almost 40% of the population saying they would not bother to vote in the 2014 EU elections.[167] Euro-Atlantic integration became a priority for the country since the fall of Communism, although the Communist leadership also had aspirations of leaving the Warsaw Pact and joining the European Communities by 1987.[168][169][170] Bulgaria's relationship with its neighbours since 1990 has generally been good. The country also plays an important role in promoting regional security.[171] Bulgaria has an active tripartite economic and diplomatic collaboration with Romania and Greece,[172] maintains strong relations with EU members, the United States and Russia, and continues to improve its traditionally good ties with China[173] and Vietnam.[174] The HIV trial in Libya, which followed after the imprisonment of several Bulgarian nurses in Benghazi in 1998, had a significant impact on relations between Bulgaria, the European Union, and Libya. It resulted in the release of the nurses by Muammar Gaddafi's government, which was granted a contract to receive a nuclear reactor and weapons supplies from France in exchange.[175]

Bulgaria hosted six KC-135 Stratotanker aircraft and 200 support personnel for the war effort in Afghanistan in 2001, which was the first stationing of foreign forces on its territory since World War II.[13] International military relations were further expanded in April 2006, when Bulgaria and the United States signed a defence cooperation agreement providing for the usage of Bezmer and Graf Ignatievo air bases, the Novo Selo training range, and a logistics centre in Aytos as joint military training facilities.[176] The same year Foreign Policy magazine listed Bezmer Air Base as one of the six most important overseas facilities used by the USAF due to its proximity to the Middle East.[177] A total of 756 troops are deployed abroad as part of various UN and NATO missions. Historically, Bulgaria deployed significant numbers of military and civilian advisors in Soviet-allied countries, such as Nicaragua[178] and Libya (more than 9,000 personnel).[179]

Domestic defence is the responsibility of the all-volunteer military of Bulgaria, consisting of land forces, navy and air force. The land forces consist of two mechanised brigades and eight independent regiments and battalions; the air force operates 106 aircraft and air defence systems in six air bases, and the navy operates a variety of ships, helicopters and coastal defence measures.[180] Following a series of reductions beginning in 1990, the number of active troops contracted from 152,000 in 1988[181] to about 32,000 in the 2000s,[182] supplemented by a reserve force of 302,500 soldiers and officers and 34,000 paramilitary servicemen.[183] The inventory is mostly of Soviet origin, such as MiG-29 fighters, SA-10 Grumble SAMs and SS-21 Scarab short-range ballistic missiles. By 2020 the government will spend $1.4 billion for the deployment of new fighter jets, communications systems and cyber warfare capabilities.[184] Total military spending in 2009 cost $819 million.[185]

Economy

Bulgaria has an emerging market economy[186] in the upper middle income range,[187] where the private sector accounts for more than 80 per cent of GDP.[188] From a largely agricultural country with a predominantly rural population in 1948, by the 1980s Bulgaria had transformed into an industrial economy with scientific and technological research at the top of its budgetary expenditure priorities.[189] The loss of COMECON markets in 1990 and the subsequent "shock therapy" of the planned system caused a steep decline in industrial and agricultural production, ultimately followed by an economic collapse in 1997.[190][191] The economy largely recovered during a period of rapid growth several years later,[190] but the average salary remains one of the lowest in the EU at 820 leva (€419) per month in September 2014.[192] More than a fifth of the labour force are employed on a minimum wage of €1 per hour.[193] Wages, however, account for only half of the total household income,[194] owing to the substantial informal economy which amounts to almost 32% of GDP.[195] Bulgarian PPS GDP per capita stood at 47 per cent of the EU average in 2013 according to Eurostat data,[196] while the cost of living was 48 per cent of the average.[197] The currency is the lev, which is pegged to the euro at a rate of 1.95583 levа for 1 euro.[198] Bulgaria is not part of the eurozone and has abandoned its plans to adopt the euro.[199]

Economic indicators have worsened amid the late-2000s financial crisis. After several consecutive years of high growth, GDP contracted 5.5 per cent in 2009 and unemployment remains above 12 per cent.[200][201] Industrial output declined 10 per cent, mining by 31 per cent, and ferrous and metal production marked a 60 per cent drop.[202] Positive growth was restored in 2010,[201] although investments and consumption continue to decline steadily due to rising unemployment.[203] The same year, intercompany debt exceeded €51 billion, meaning that 60 per cent of all Bulgarian companies were mutually indebted.[204] By 2012, it had increased to €83 billion, or 227 per cent of GDP.[205] The government implemented strict austerity measures with IMF and EU encouragement to some positive fiscal results, but the social consequences of these measures have been "catastrophic" according to the International Trade Union Confederation.[206] Corruption remains another obstacle to economic growth. Bulgaria is one of the most corrupt European Union members and ranks 75th in the Corruption Perceptions Index.[207] Weak law enforcement and overall low capacity of civil service remain as challenges in curbing corruption. However, fighting against corruption has become the focus of the government because of the EU accession, and several anti-corruption programs have been undertaken by different government agencies.[208]

Economic activities are fostered by the lowest personal and corporate income tax rates in the EU,[209] and the second-lowest public debt of all member states at 16.5 per cent of GDP in 2012.[210] In 2013, GDP (PPP) was estimated at $119.6 billion, with a per capita value of $16,518.[3] Sofia and the surrounding Yugozapaden planning area are the most developed region of the country with a per capita PPS GDP of $27,282 in 2011.[211] Bulgaria is a net receiver of funds from the EU. The absolute amount of received funds was €589 million in 2009.[212]

The labour force is 2.45 million people,[213] of whom 7.1 per cent are employed in agriculture, 35.2 per cent are employed in industry and 57.7 per cent are employed in the services sector.[214] Extraction of metals and minerals, production of chemicals, machinery and vehicle components,[215] petroleum refining[216] and steel are among the major industrial activities.[217] Mining and its related industries employ a total of 120,000 people and generate about five per cent of the country's GDP.[218] Bulgaria is Europe's sixth-largest coal producer.[218][219] Local deposits of coal, iron, copper and lead are vital for the manufacturing and energy sectors.[220] Almost all top export items of Bulgaria are industrial commodities such as oil products, copper products and pharmaceuticals.[221] Bulgaria is also a net exporter of agricultural and food products, of which two-thirds go to OECD countries.[222] It is the largest global producer of perfumery essential oils such as lavender and rose oil.[13][223] Agriculture has declined significantly in the past two decades. Production in 2008 amounted to only 66 per cent of that between 1999 and 2001,[221] while cereal and vegetable yields have dropped by nearly 40 per cent since 1990.[224] Of the services sector, tourism is the most significant contributor to economic growth.[225] In recent years, Bulgaria has emerged as a travelling destination with its inexpensive resorts and beaches outside the reach of the tourist industry.[226][227] Lonely Planet ranked it among its top 10 destinations for 2011.[228] Most of the visitors are British, Romanian, German and Russian.[229] The capital Sofia, the medieval capital Veliko Tarnovo,[230] coastal resorts Golden Sands and Sunny Beach and winter resorts Bansko, Pamporovo and Borovets are some of the locations most visited by tourists.[225]

Science and technology

Bulgaria spends 0.25 per cent of GDP on scientific research, thus having one of the lowest R&D budgets in Europe.[231][232] Chronic underinvestment in research since 1990 forced many scientific professionals to leave the country.[233] As a result, Bulgaria scores low in terms of innovation, competitiveness and high-value added exports.[234][235] Principal areas of research and development are energy, nanotechnology, archaeology and medicine.[231] The Bulgarian Academy of Sciences (BAS) is the leading scientific establishment and employs most Bulgarian researchers in its numerous institutes. It has been active in the field of space science with RADOM-7 radiation monitoring experiments on the International Space Station[236] and Chandrayaan-1,[237] and domestically developed space greenhouses on the Mir space station.[238][239] Bulgaria became the sixth country in the world to have an astronaut in space with Georgi Ivanov's flight on Soyuz 33 in 1979. Bulgaria is an active member of CERN and has contributed to its activities with nearly 200 scientists since its accession in 1999.[240][241]

In the 1980s Bulgaria was known as the "Silicon Valley of the Eastern Bloc" because of its large-scale computing technology exports to COMECON states.[242] The ICT sector generates 10 per cent of GDP[243] and employs the third-largest contingent of ICT specialists in the world. A National Centre for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA) operates the only supercomputer in Southeastern Europe.[244][245] The Bulgarian Academy of Sciences is planning to buy another supercomputer in 2015 which will be used together with Hi-Tech SME's.[246]

Internet usage has increased rapidly since 2000—the number of users grew from 430,000 to 3.4 million (48 per cent penetration rate) in 2010.[247] Telephone services are widely available, and a central digital trunk line connects most regions.[248] More than 90 per cent of fixed lines are served by the Bulgarian Telecommunications Company (BTC),[249] while mobile services are provided by three operators—Mtel, GLOBUL and BTC/Vivacom.[250]

Infrastructure

Bulgaria's strategic geographic location and well-developed energy sector make it a key European energy centre despite its lack of significant fossil fuel deposits.[251] Nearly 34 percent of its electricity is produced by the nuclear power station at Kozloduy[252] and public opinion strongly supports nuclear energy development.[253] The rapid expansion of alternative energy sources such as wind and solar power stations[254] make Bulgaria one of the fastest-growing wind energy producers in the world.[255] The country aims to produce 16 percent of its electricity from renewable energy sources by 2020.[256]

The national road network has a total length of 40,231 kilometres (24,998 mi),[257] of which 39,587 kilometres (24,598 mi) are paved, but nearly half fall into the lowest international rating for paved roads.[248] Railroads are a major mode of freight transportation, although highways carry a progressively larger share of freight. Bulgaria has 6,238 kilometres (3,876 mi) of railway track[248] and currently a total of 81 km of high-speed lines are in operation.[258][259][260][261] Rail links are available with Romania, Turkey, Greece, and Serbia, and express trains serve direct routes to Kiev, Minsk, Moscow and Saint Petersburg.[262] Sofia and Plovdiv are the country's air travel hubs, while Varna and Burgas are the principal maritime trade ports.[248] Varna is also scheduled to be the first station on EU territory to receive natural gas through the South Stream pipeline.[263]

Demographics

The population of Bulgaria is 7,364,570 people according to the 2011 national census. The majority of the population, or 72.5 per cent, reside in urban areas;[2] approximately one-sixth of the total population is concentrated in Sofia.[265][266] Bulgarians are the main ethnic group and comprise 84.8 per cent of the population. Turkish and Roma minorities comprise 8.8 and 4.9 per cent, respectively; some 40 smaller minorities comprise 0.7 per cent, and 0.8 per cent do not self-identify with an ethnic group.[267] All ethnic groups speak Bulgarian, either as a first or as a second language. Bulgarian is the only language with official status and native for 85.2 per cent of the population. The oldest written Slavic language, Bulgarian is distinguishable from the other languages in this group through certain grammatical peculiarities such as the lack of noun cases and infinitives, and a suffixed definite article.[268][269]

Bulgaria is in a state of demographic crisis.[270][271] It has had negative population growth since the early 1990s, when the economic collapse caused a long-lasting emigration wave.[272] Some 937,000 to 1,200,000 people—mostly young adults—left the country by 2005.[272][273] The total fertility rate (TFR) was estimated in 2013 at 1.43 children born/woman, which is below the replacement rate of 2.1.[274] A third of all households consist of only one person and 75.5 per cent of families do not have children under the age of 16.[271] Consequently, population growth and birth rates are among the lowest in the world[275][276] while death rates are among the highest.[277] The majority of children are born to unmarried women (of all births 57.4 per cent were outside marriage in 2012).[278] Bulgaria ranks 113th globally by average life expectancy, which stands at 73.6 years for both genders.[279] The primary causes of death are similar to those in other industrialised countries, mainly cardiovascular diseases, neoplasms and respiratory diseases.[280]

Bulgaria has a universal healthcare system financed by taxes and contributions.[280] The National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF) pays a gradually increasing portion of the costs of primary healthcare.[281] Projected healthcare expenditures for 2013 amount to 4.1 per cent of GDP.[282] The number of doctors is above the EU average with 181 physicians per 100,000 people,[283] but distribution by fields of practice is uneven, there is a severe shortage of nurses and other medical personnel, and the quality of most medical facilities is poor.[284] Personnel shortages in some fields are so severe that patients resort to seeking treatment in neighboring countries.[285]

Government estimates from 2003 put the literacy rate at 98.6 per cent, with no significant difference between the sexes. Educational standards have been traditionally high,[286] although still far from European benchmarks and in continuing deterioration for the past decade.[287] Bulgarian students were among the highest-scoring in the world in terms of reading in 2001, performing better than their Canadian and German counterparts; by 2006, scores in reading, math and science had deteriorated. State expenditures for education are far below the European Union average.[287] The Ministry of Education, Youth and Science partially funds public schools, colleges and universities, sets criteria for textbooks and oversees the publishing process.[288] The State provides free education in primary and secondary public schools.[286] The educational process spans through 12 grades, where grades one through eight are primary and nine through twelve are secondary level.[288] High schools can be technical, vocational, general or specialised in a certain discipline, while higher education consists of a 4-year bachelor degree and a 1-year Master's degree.[289]

The Constitution of Bulgaria defines it as a secular state with guaranteed religious freedom, but designates Orthodoxy as a "traditional" religion.[290] The Bulgarian Orthodox Church gained autocephalous status in 927 AD,[291][292] and currently has 12 dioceses and over 2,000 priests.[293] More than three-quarters of Bulgarians subscribe to Eastern Orthodoxy.[294] Sunni Muslims are the second-largest community and constitute 10 per cent of the religious makeup, although a majority of them do not pray and find the use of Islamic veils in schools unacceptable.[295] Less than three per cent are affiliated with other religions, 11.8 per cent do not self-identify with a religion and 21.8 per cent refused to state their beliefs.[294]

Culture

Traditional Bulgarian culture contains mainly Thracian, Slavic and Bulgar heritage, along with Greek, Roman, Ottoman, Persian and Celtic influences.[296][297][298] Nine historical and natural objects have been inscribed in the list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites: the Madara Rider, the Thracian tombs in Sveshtari and Kazanlak, the Boyana Church, the Rila Monastery, the Rock-hewn Churches of Ivanovo, Pirin National Park, Sreburna Nature Reserve and the ancient city of Nesebar.[299] Nestinarstvo, a ritual fire-dance of Thracian origin,[300] is included in the list of UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage.[301] Fire is an essential element of Bulgarian folklore, used to banish evil spirits and diseases. Bulgarian folklore personifies illnesses as witches and has a wide range of creatures, including lamya, samodiva (veela) and karakondzhul.[302] Some of the customs and rituals against these spirits have survived and are still practised, most notably the kukeri and survakari.[303] Martenitsa is also widely celebrated.[304]

Slavic culture was centred in both the First and Second Bulgarian Empires during much of the Middle Ages. The Preslav, Ohrid and Tarnovo literary schools exerted considerable cultural influence over the Eastern Orthodox world.[305][306][307] Many languages in Eastern Europe and Asia use Cyrillic script, which originated in the Preslav Literary School around the 9th century.[308] The medieval advancement in the arts and letters ended with the Ottoman conquest when many masterpieces were destroyed, and artistic activities did not re-emerge until the National Revival in the 19th century.[309] After the Liberation, Bulgarian literature quickly adopted European literary styles such as Romanticism and Symbolism. Since the beginning of the 20th century, several Bulgarian authors, such as Ivan Vazov, Pencho Slaveykov, Peyo Yavorov, Yordan Radichkov and Tzvetan Todorov have gained prominence.[310][311] In 1981 Bulgarian-born writer Elias Canetti was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature.[312]

Bulgarian folk music is by far the most extensive traditional art and has slowly developed throughout the ages as a fusion of Eastern and Western influences. It contains Far Eastern, Oriental, medieval Eastern Orthodox and standard Western European tonalities and modes.[313] The music has a distinctive sound and uses a wide range of traditional instruments, such as gadulka, gaida (bagpipe), kaval and tupan. One of its most distinguishing features is extended rhythmical time, which has no equivalent in the rest of European music.[13] The State Television Female Vocal Choir is the most famous performing folk ensemble, and received a Grammy Award in 1990.[314] Bulgaria's written musical composition can be traced back to the early Middle Ages and the works of Yoan Kukuzel (c. 1280–1360).[315] Classical music, opera and ballet are represented by composers Emanuil Manolov, Pancho Vladigerov and Georgi Atanasov and singers Ghena Dimitrova, Boris Hristov and Nikolay Gyaurov.[316][317][318][319][320] Bulgarian performers have gained popularity in several other genres like progressive rock (FSB), electropop (Mira Aroyo) and jazz (Milcho Leviev).

The religious visual arts heritage includes frescoes, murals and icons, many produced by the medieval Tarnovo Artistic School.[321] Vladimir Dimitrov, Nikolay Diulgheroff and Christo are some of the most famous modern Bulgarian artists.[309] Film industry remains weak: in 2010, Bulgaria produced three feature films and two documentaries with public funding. Cultural events are advertised in the largest media outlets, including the Bulgarian National Radio, and daily newspapers Dneven Trud, Dnevnik and 24 Chasa.[322]

Bulgarian cuisine is similar to those of other Balkan countries and demonstrates a strong Turkish and Greek influence.[323] Yogurt, lukanka, banitsa, shopska salad, lyutenitsa and kozunak are among the best-known local foods. Oriental dishes such as moussaka, gyuvech, and baklava are also present. Meat consumption is lower than the European average, given a notable preference for a large variety of salads.[323] Rakia is a traditional fruit brandy which was consumed in Bulgaria as early as the 14th century.[324] Bulgarian wine is known for its Traminer, Muskat and Mavrud types, of which up to 200,000 tonnes are produced annually.[325][326] Until 1989, Bulgaria was the world's second-largest wine exporter.[327]

_(9377376402).jpg)

Bulgaria performs well in sports such as wrestling, weight-lifting, boxing, gymnastics, volleyball, football and tennis.[328] The country fields one of the leading men's volleyball teams, ranked sixth in the world according to the 2013 FIVB rankings.[329] Football is by far the most popular sport.[328] Some famous players are AS Monaco forward Dimitar Berbatov and Hristo Stoichkov, winner of the Golden Boot and the Golden Ball and the most successful Bulgarian player of all time.[330] Prominent domestic clubs include PFC CSKA Sofia[331][332] and PFC Levski Sofia. The best performance of the national team at FIFA World Cup finals came in 1994, when it advanced to the semi-finals by defeating consecutively Greece, Argentina, Mexico and Germany, finishing fourth.[328] Bulgaria has participated in most Olympic competitions since its first appearance at the 1896 games, when it was represented by Charles Champaud.[333] The country has won a total of 218 medals: 52 gold, 86 silver, and 80 bronze,[334] which puts it in 24th place in the all-time ranking.

See also

- Outline of Bulgaria

- International rankings of Bulgaria

- List of twin towns and sister cities in Bulgaria

Footnotes

- ↑ 19 February in the Julian calendar used at the time.

- ↑ 22 September in the Julian calendar used at the time.

References

- ↑ 2011 census, p. 4.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2011 census, p. 3

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 "Bulgaria". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- ↑ "Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income (source: SILC)". Eurostat Data Explorer. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- ↑ "Human Development Report 2014 – "Sustaining Human Progress: Reducing Vulnerabilities and Building Resilience"". HDRO (Human Development Report Office) United Nations Development Programme. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ↑ "Early human marks are 'symbols'". BBC News. 16 March 2004. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- ↑ Slavchev, Vladimir (2004–2005). Monuments of the final phase of Cultures Hamangia and Savia on the territory of Bulgaria (PDF). Revista Pontica. 37–38. pp. 9–20. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ↑ Chapman, John (2000). Fragmentation in Archaeology: People, Places, and Broken Objects. Routledge. p. 239. ISBN 978-0-415-15803-9.

- ↑ Roberts, Benjamin W.; Thornton, Christopher P. (2009). "Development of metallurgy in Eurasia". Department of Prehistory and Europe, British Museum. p. 1015. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

In contrast, the earliest exploitation and working of gold occurs in the Balkans during the mid-fifth millennium BC, several centuries after the earliest known copper smelting. This is demonstrated most spectacularly in the various objects adorning the burials at Varna, Bulgaria (Renfrew 1986; Highamet al. 2007). In contrast, the earliest gold objects found in Southwest Asia date only to the beginning of the fourth millennium BC as at Nahal Qanah in Israel (Golden 2009), suggesting that gold exploitation may have been a Southeast European invention, albeit a short-lived one.

- ↑ Sigfried J. de Laet, ed. (1996). History of Humanity: From the Third Millennium to the Seventh Century BC. UNESCO / Routledge. p. 99. ISBN 978-92-3-102811-3. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

The first major gold-working centre was situated at the mouth of the Danube, on the shores of the Black Sea in Bulgaria ...

- ↑ Grande, Lance (2009). Gems and gemstones: Timeless natural beauty of the mineral world. The University of Chicago Press. p. 292. ISBN 978-0-226-30511-0. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

The oldest known gold jewelry in the world is from an archaeological site in Varna Necropolis, Bulgaria, and is over 6,000 years old (radiocarbon dated between 4,600BC and 4,200BC).

- ↑ "The Gumelnita Culture". Government of France. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

The Necropolis at Varna is an important site in understanding this culture.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 "Bulgaria Factbook". United States Central Command. Retrieved December 2011.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "Bulgar (people)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ↑ Boardman, John; Edwards, I.E.S.; Sollberger, E. (1982). The Cambridge Ancient History - part1: The Prehistory of the Balkans, the Middle East and the Aegean World, Tenth to Eighth Centuries BC 3. Cambridge University Press. p. 53. ISBN 0521224969.

Yet we cannot identify the Thracians at that remote period, because we do not know for certain whether the Thracian and Illyrian tribes had separated by then. It is safer to speak of Proto-Thracians from whom there developed in the Iron Age...

- ↑ Nagle, D. Brendan (2006). Readings in Greek History: Sources and Interpretations. Oxford University Press. p. 230. ISBN 0-19-517825-4.

However, one of the Thracian tribes, the Odrysians, succeeded in unifying the Thracians and creating a powerful state

- ↑ Hornblower, Simon (2003). The Oxford Classical Dictionary. Oxford University Press. p. 1515. ISBN 0-19-860641-9.

Shortly afterwards the first King of the Odrysae, Teres attempted to carve an empire out of the territory occupied by the Thracian tribes (Thuc.2.29 and his sovereignty extended as far as the Euxine and the Hellespont)

- ↑ Ivanov, Lyubomir (2007). ESSENTIAL HISTORY OF BULGARIA IN SEVEN PAGES. Bulgarian Academy of Sciences. p. 2. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

In particular, in the mid-4th century a group of Goths settled in the region of Nikopolis ad Istrum (present Nikyup near Veliko Tarnovo in northern Bulgaria), where their leader Bishop Wulfila (Ulfilas) invented the Gothic alphabet and translated the Holy Bible into Gothic to produce the first book written in Germanic language.

- ↑ Hock, Hans Heinrich; Joseph, Brian D. (1996). Language History, Language Change and Language Relationship: an introduction to historical and comparative linguistics. Walter de Gruyter & Co. p. 49. ISBN 3-11-014784-X. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

The oldest extensive text is a Gothic Bible translation produced by the Gothic bishop Wulfilas (meaning 'Little Wolf') in the 4th century

- ↑ "The monastery in the village of Zlatna Livada - the oldest in Europe" (in Bulgarian). LiterNet. 30 April 2004. Retrieved 30 March 2012.

- ↑ D. Angelov (1971). "The Formation of the Bulgarian Nation". Наука и изкуство, "Векове". pp. 409–410.

- ↑ Browning, Robert (1988). Byzantium and Bulgaria. Studia Slavico-Byzantina et Mediaevalia Europensia I. pp. 32–36.

- ↑ Zlatarski, Vasil (1938). History of the First Bulgarian Empire. Period of Hunnic-Bulgarian domination (679-852) (in Bulgarian). p. 188. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- ↑ Runciman, Steven (1930). A History of the First Bulgarian Empire. G. Bell and Sons. p. 26.

- ↑ Ivanov, Lyubomir (2007). ESSENTIAL HISTORY OF BULGARIA IN SEVEN PAGES. Bulgarian Academy of Sciences. pp. 2–3. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ↑ "Krum (Bulgar khan)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

- ↑ "The Spread of Christianity". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 27 July 2014.

Although Boris’s baptism was into the Eastern church, he subsequently wavered between Rome and Constantinople until the latter was persuaded to grant de facto autonomy to Bulgaria in church affairs.

- ↑ Crampton, R.J. (2007). Bulgaria. Oxford University Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-19-954158-4.

- ↑ "Reign of Simeon I". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 27 July 2014.

Bulgaria’s conversion had a political dimension, for it contributed both to the growth of central authority and to the merging of Bulgars and Slavs into a unified Bulgarian people.

- ↑ Crampton, R.J. (2007). Bulgaria. Oxford

University Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-19-954158-4.

No single act did more, in the long run, to weld Christian Slav and Proto-Bulgar into a Bulgarian people than the conversion of 864.

- ↑ The First Golden Age.

- ↑ "Reign of Simeon I". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

Under Simeon's successors Bulgaria was beset by internal dissension provoked by the spread of Bogomilism (a dualist religious sect) and by assaults from Magyars, Pechenegs, the Rus, and Byzantines.

- ↑ Browning, Robert (1975). Byzantium and Bulgaria. Temple Smith. pp. 194–5. ISBN 0-85117-064-1.

- ↑ "Reign of Simeon I". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- ↑ "Samuel". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- ↑ Scylitzae, Ioannis (1973). Synopsis Historiarum. Corpus Fontium Byzantiae Historiae (Hans Thurn ed.). p. 457. ISBN 978-3-11-002285-8.

- ↑ Pavlov, Plamen (2005). "The plots of 'master Presian the Bulgarian'". Rebels and adventurers in medieval Bulgaria (in Bulgarian). LiterNet. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

And, in the Spring of 1018, "the party of capitulation" prevailed and Basil II freely entered the then capital of Bulgaria Ochrid.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Ostrogorsky, Georg (1969). History of the Byzantine State. Rutgers University Press. p. 311.

- ↑ Cameron, Averil (2006). The Byzantines. Blackwell Publishing. p. 170. ISBN 978-1-4051-9833-2.

- ↑ "Bulgaria – Second Bulgarian Empire". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 31 March 2012.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 41.3 James David Bourchier (1911). "History of Bulgaria". Encyclopædia Britannica 1911. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- ↑ Ivanov, Lyubomir (2007). ESSENTIAL HISTORY OF BULGARIA IN SEVEN PAGES. Bulgarian Academy of Sciences. p. 4. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

The capital Tarnovo became a political, economic, cultural and religious centre seen as 'the Third Rome' in contrast to Constantinople's decline after the Byzantine heartland in Asia Minor was lost to the Turks during the late 11th century.

- ↑ "The Golden Horde". Library of Congress Mongolia country study. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

The Mongols maintained sovereignty over eastern Russia from 1240 to 1480, and they controlled the upper Volga area, the territories of the former Volga Bulghar state, Siberia, the northern Caucasus, Bulgaria (for a time), the Crimea, and Khwarizm

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 "Bulgaria – Ottoman rule". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

With the capture of a rump Bulgarian kingdom centred at Bdin (Vidin) in 1396, the last remnant of Bulgarian independence disappeared. ... The Bulgarian nobility was destroyed—its members either perished, fled, or accepted Islam and Turkicization—and the peasantry was enserfed to Turkish masters.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Jireček, K. J. (1876). Geschichte der Bulgaren (in German). Nachdr. d. Ausg. Prag. ISBN 3-487-06408-1. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ↑ Minkov, Anton (2004). Conversion to Islam in the Balkans: Kisve Bahası - Petitions and Ottoman Social Life, 1670–1730. BRILL. p. 193. ISBN 90-04-13576-6.

- ↑ Detrez, Raymond (2008). Europe and the Historical Legacies in the Balkans. Peter Lang Publishers. p. 36. ISBN 90-5201-374-8.

- ↑ Fishman, Joshua A. (2010). "Handbook of Language and Ethnic Identity," Disciplinary and Regional Perspectives. Oxford University Press. p. 276. ISBN 0-19-537492-4.

There were almost no remnants of a Bulgarian ethnic identity; the population defined itself as Christians, according to the Ottoman system of millets, that is, communities of religious beliefs. The first attempts to define a Bulgarian ethnicity started at the beginning of the 19-th century.

- ↑ Roudometof, Victor; Robertson, Roland (2001). Nationalism, globalization, and orthodoxy: the social origins of ethnic conflict in the Balkans. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 68–71. ISBN 0-313-31949-9.

- ↑ Crampton, R. J. (1987). Modern Bulgaria. Cambridge University Press. p. 8. ISBN 0-521-27323-4. Retrieved 2013-10-02.

- ↑ Carvalho, Joaquim (2007). Religion and Power in Europe: Conflict and Convergence. Edizioni Plus. p. 261. ISBN 88-8492-464-2.

- ↑ "Bulgaria – Ottoman administration". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 The Final Move to Independence.

- ↑ "Reminiscence from Days of Liberation*". Novinite. 3 March 2011. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 San Stefano, Berlin and Independence.

- ↑ Blamires, Cyprian (2006). World Fascism: A historical encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 107. ISBN 1-57607-941-4. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

The "Greater Bulgaria" re-established in March 1878 on the lines of the medieval Bulgarian empire after liberation from Turkish rule did not last long.

- ↑ "Timeline: Bulgaria – A chronology of key events". BBC News. 6 May 2010. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ↑ Historical Setting.

- ↑ Crampton, R.J. (2007). Bulgaria. Oxford University Press. p. 174. ISBN 978-0-19-954158-4.

- ↑ Dillon, Emile Joseph (February 1920). "XV". The Inside Story of the Peace Conference. Harper. ISBN 978-3-8424-7594-6. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

The territorial changes which the Prussia of the Balkans was condemned to undergo are neither very considerable nor unjust.

- ↑ Pinon, Rene (1913). L'Europe et la Jeune Turquie: les aspects nouveaux de la question d'Orient (in French). Perrin et cie. ISBN 978-1-144-41381-9. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

On a dit souvent de la Bulgarie qu'elle est la Prusse des Balkans

- ↑ Tucker, Spencer C; Wood, Laura (1996). The European Powers in the First World War: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. p. 173. ISBN 0-8153-0399-8.

- ↑ Broadberry, Stephen; Klein, Alexander (8 February 2008). "Aggregate and Per Capita GDP in Europe, 1870–2000: Continental, Regional and National Data with Changing Boundaries" (PDF). Department of Economics at the University of Warwick, Coventry. p. 18. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ↑ "WWI Casualty and Death Tables". PBS. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ↑ Mintchev, Vesselin (October 1999). "External Migration in Bulgaria". South-East Europe Review (3/99): 124. Retrieved 8 May 2013.

- ↑ Chenoweth, Erica (2010). Rethinking Violence: States and Non-State Actors in Conflict. Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-262-01420-5.

Bulgaria, for example, had a net surplus of refugees and was faced with the daunting task of absorbing thousands of Bulgarian refugees from Greece over a relatively short period. While international loans from the Red Cross and other organizations helped to defray the substantial costs of accommodating surplus populations, it placed a strenuous financial burden on states that were still recovering from the war an experiencing economic downturn as well as political upheaval.

- ↑ Bulgaria in World War II: The Passive Alliance.

- ↑ Wartime Crisis.

- ↑ Pavlowitch, Stevan K. (2008). Hitler's new disorder: the Second World War in Yugoslavia. Columbia University Press. pp. 238–240. ISBN 0-231-70050-4. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

When Bulgaria switched sides in September...

- ↑ Crampton, R. J. (2005). A concise history of Bulgaria. Cambridge University Press. p. 271. ISBN 0-521-61637-9. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ↑ Hanna Arendt Center in Sofia, with Dinyu Sharlanov and Venelin I. Ganev. Crimes Committed by the Communist Regime in Bulgaria. Country report. "Crimes of the Communist Regimes" Conference. 24–26 February 2010, Prague.

- ↑ Valentino, Benjamin A (2005). Final solutions: mass killing and genocide in the twentieth century. Cornell University Press. pp. 91–151.

- ↑ Rummel, Rudolph, Statistics of Democide, 1997.

- ↑ Domestic Policy and Its ResultsQuote: "...real wages increased 75 percent, consumption of meat, fruit, and vegetables increased markedly, medical facilities and doctors became available to more of the population..."

- ↑ After Stalin.

- ↑ Stephen Broadberry; Alexander Klein (27 October 2011). "Aggregate and per capita GDP in Europe, 1870-2000" (PDF). pp. 23, 27. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ↑ Vachkov, Daniel; Ivanov, Martin (2008). Bulgarian Foreign Debt 1944-1989. Siela. pp. 103, 153, 191. ISBN 9789542803072.

- ↑ The Economy.

- ↑ The Political Atmosphere in the 1970s.

- ↑ Bohlen, Celestine (17 October 1991). "Vote Gives Key Role to Ethnic Turks". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

in 1980s ... the Communist leader, Todor Zhivkov, began a campaign of cultural assimilation that forced ethnic Turks to adopt Slavic names, closed their mosques and prayer houses and suppressed any attempts at protest. One result was the mass exodus of more than 300,000 ethnic Turks to neighboring Turkey in 1989

- ↑ "Cracks show in Bulgaria's Muslim ethnic model". Reuters. 31 May 2009. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- ↑ Government and Politics.

- ↑ "Bulgarian Politicians Discuss First Democratic Elections 20y After". Novinite. 5 July 2010. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ↑ "The destructive Bulgarian transition". Le Monde diplomatique (in Bulgarian). 1 October 2007. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ↑ World Socialist Web Site (24 July 2001). "Ex-King Simeon II named new prime minister of Bulgaria". Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 86.2 86.3 Library of Congress 2006, p. 16.

- ↑ "Human Development Index Report" (PDF). United Nations. 2005. p. 220. Retrieved 4 December 2011. Compare with 2004 Report, page 140. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ↑ 88.0 88.1 "NATO Update: Seven new members join NATO". NATO. 29 March 2004. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ↑ 89.0 89.1 Bos, Stefan (1 January 2007). "Bulgaria, Romania Join European Union". VOA News (Voice of America). Retrieved 2 January 2009.

- ↑ 90.0 90.1 90.2 90.3 90.4 90.5 Library of Congress 2006, p. 4.

- ↑ Penin, Rumen (2007). Природна география на България. Bulvest 2000. p. 18. ISBN 978-954-18-0546-6.(in Bulgarian)

- ↑ "Countries ranked by area". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ↑ "Bulgaria". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ↑ "Мусала". Българска енциклопедия А-Я (in Bulgarian). Bulgarian Academy of Sciences / Trud. 2002. ISBN 954-8104-08-3. OCLC 163361648.

- ↑ Topography.

- ↑ Donchev, D. (2004). Geography of Bulgaria (in Bulgarian). Ciela. p. 68. ISBN 954-649-717-7.

- ↑ "Extreme temperature records worldwide". MeteorologyClimate. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ↑ Climate.

- ↑ "Kyoto Protocol Status of Ratification (pdf)" (PDF). Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ↑ "Bulgaria Achieves Kyoto Protocol Targets – IWR Report". Novinite. 11 August 2009. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ↑ Kanev, Petar (2009). "България от Космоса: сеч, пожари, бетон ... и надежда". *8* Magazine (in Bulgarian) (Klub 8) (2).

- ↑ "Bulgaria’s Air Is Dirtiest in Europe, Study Finds, Followed by Poland". The New York Times. 15 October 2013. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- ↑ "High Air Pollution to Close Downtown Sofia". Novinite. 14 January 2008. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ↑ "Bulgaria's Sofia, Plovdiv Suffer Worst Air Pollution in Europe". Novinite. 23 June 2010. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ↑ 105.0 105.1 "Bulgaria's quest to meet the environmental acquis". European Stability Initiative. 10 December 2008. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ↑ "Municipal waste recycling 1995–2008 (1000 tonnes)". Eurostat. 2008. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ↑ "The first factory for recycling of electronic appliances now works". Dnevnik. 28 June 2010. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ↑ "2012 Environmental Performance Index". Yale University. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- ↑ "Industrial facilities causing the highest damage costs to health and the environment". European Environment Agency. Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- ↑ "Report on European Environment Agency about the quality of freshwaters in Europe". European Environment Agency. Retrieved 21 March 2014.

- ↑ "Bulgarian NGO to Track 5 Imperial Eagles by Satellite". Novinite. 9 July 2010. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- ↑ "Характеристика на флората и растителността на България". Bulgarian-Swiss program by biodiversity. Retrieved 21 March 2013.

- ↑ "The future of Bulgaria's natural parks and their administrations". Gora Magazine. June 2010. Retrieved 20 December 2011. (in Bulgarian)

- ↑ "Will Bulgaria have any biosphere reserves?". Gora Magazine. May 2007. Retrieved 20 December 2011. (in Bulgarian)

- ↑ "Bulgaria – Environmental Summary, UNData, United Nations". United Nations. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ↑ ""The living eternity" tells about the century-old oak in the village of Granit" (in Bulgarian). Stara Zagora Local Government. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ↑ 117.0 117.1 "Bulgaria: Plant and animal life". Encyclopaedia Britannica Online. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- ↑ "Characteristics of the flora and vegetation in Bulgaria". Bulgarian-Swiss Foundation for the Protection of Biodiversity. Retrieved 20 December 2011. (in Bulgarian)

- ↑ Denchev, C. & Assyov, B. Checklist of the larger basidiomycetes ın Bulgaria. Mycotaxon 111: 279-282 (2010).

- ↑ "Brown bear conservation in Bulgaria". Frankfurt Zoological Society. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- ↑ "The big return of the lynx in Bulgaria". BirdsOfEurope. 23 May 2009. Retrieved 20 December 2011. (in Bulgarian)

- ↑ "Biodiversity in Bulgaria". Retrieved 21 March 2014.

- ↑ "Report on European Environment Agency about the Nature protection and biodiversity in Europe". European Environment Agency. Retrieved 21 March 2014.

- ↑ 125.0 125.1 125.2 Library of Congress 2006, p. 17.

- ↑ Gabriel Hershman (31 October 2011). "President-elect Plevneliev's final margin of victory closer than predicted". The Sofia Echo. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ↑ "Bulgarian Cabinet Faces No-Confidence Vote Over Atomic Plant". Bloomberg Businessweek. 6 April 2012. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ↑ "Bulgarian government resigns amid growing protests". Yahoo News. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ↑ "Protests in Bulgaria and the new practice of democracy". Al Jazeera. 21 February 2013. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ↑ "Protests in Bulgaria and the new practice of democracy". Al Jazeera. 21 February 2013. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ↑ "Rightist GERB holds lead in Bulgaria's election". Reuters. 12 May 2013. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ↑ "PM Hopeful: New Bulgarian Cabinet Will Be 'Expert, Pragmatic'". Novinite.com. Sofia News Agency. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- ↑ Buckley, Neil (2013-05-29). "Bulgaria parliament votes for a ‘Mario Monti’ to lead government". FT.com. Retrieved 2013-06-04.

- ↑ Seiler Bistra; Emiliyan Lilov (26 June 2013). "Bulgarians protest government of 'oligarchs'". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- ↑ "Birth of a civil society". The Economist. 21 September 2013. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- ↑ "Timeline of Oresharski's Cabinet: A Government in Constant Jeopardy". Novinite.com. Sofia News Agency. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ↑ "President Plevneliev Urges Outgoing Parliament to Review Budget". Novinite.com. Sofia News Agency. Retrieved 9 July 2014.

- ↑ "Bulgarian Gov't to Resign between July 23, 25 - PM Oresharski". Novinite.com. Sofia News Agency. Retrieved 9 July 2014.

- ↑ "Bulgaria's PM Plamen Oresharski Resigns". Novinite.com. Sofia News Agency. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ↑ "Bulgarian Parliament Approves Government Resignation". Novinite.com. Sofia News Agency. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ↑ "GERB Leader Boiko Borisov Returns Mandate". Novinite.com. Sofia News Agency. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ↑ "Bulgarian Socialist Party Returns Mandate". Novinite.com. Sofia News Agency. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ↑ "Bulgaria's 3rd Biggest Party, DPS, Rejects Mandate to Form Govt". Novinite.com. Sofia News Agency. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ↑ "Mandate distribution methodics". Central Electoral Commission. October 2014. Retrieved 28 October 2014.

- ↑ "Bulgaria's 42nd Parliament Dissolved, Elections on October 5". Novinite.com. Sofia News Agency. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

- ↑ Petrov, Angel. "Bulgaria's Grand Parliament Chessboard Might Be Both Ailment and Cure". Novinite.com. Sofia News Agency. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ↑ "Bulgaria: EPP President welcomes new coalition government led by Boyko Borissov (EN+BG)". http://www.epp.eu/''. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ↑ "Bulgarian parties approve coalition agreement, cabinet". http://www.euractiv.com/''. EurActiv. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ↑ "GERB and Reformist block finally sign a coalition agreement, the new cabinet to be voted today". www.ffbh.bg. FFBH. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ↑ Bulgaria's GERB Party Signs Partnership Deal with Left-Wing ABV

- ↑ "Bulgarian MPs Approve New Cabinet, Ministers Sworn In". Novinite.com. Sofia News Agency. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ↑ "Bulgaria's Parliament Approves New Government". abcnews.go.com. ABC News Internet Ventures. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ↑ "The Bulgarian Legal System and Legal Research". Hauser Global Law School Program. August 2006. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ↑ "Съдебната ни система – първенец по корупция" (in Bulgarian). News.bg. 3 June 2010. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ↑ Brunwasser, Matthew (5 November 2006). "Questions arise again about Bulgaria's legal system". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ↑ "Transparency International report: Bulgaria perceived as EU's most corrupt country". Bulgarian National Radio. 1 December 2012. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- ↑ "Bulgaria Sets Up Anti-Corruption Unit; Security Chief Steps Down". Bloomberg. 17 February 2011. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- ↑ Interpol. "Interpol entry on Bulgaria". Interpol. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ↑ "National Police Service". Ministry of Interior of Bulgaria. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ↑ "Official: The policemen in Bulgaria are almost 27,000". Vsekiden (in Bulgarian). 19 January 2010. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ↑ "State Agency for National Security Official Website". State Agency for National Security. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ↑ "LOCAL STRUCTURES IN BULGARIA". Council of European Municipalities and Regions. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ↑ "Historical development of the administrative and territorial division of the Republic of Bulgaria" (in Bulgarian). Ministry of Regional Development. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ↑ "The oblasts in Bulgaria. Portraits". Ministry of Regional Development. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ↑ "The United Nations Security Council". The Green Papers Worldwide. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ↑ "European Commission Enlargement Archives: Treaty of Accession of Bulgaria and Romania". European Commission. 25 April 2005. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ↑ Popkostadinova, Nikoleta (3 March 2014). "Angry Bulgarians feel EU membership has brought few benefits". EUobserver. Retrieved 5 March 2014.