Buffalo, New York

| Buffalo, New York | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| City | |||

| City of Buffalo | |||

|

Clockwise from top: Downtown Buffalo, Buffalo skyline at dusk, Peace Bridge, Buffalo Savings Bank, County and City Hall, Niagara Square, and the Buffalo City Hall. | |||

| |||

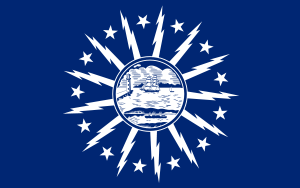

| Nickname(s): The City of Good Neighbors, The Queen City, The City of No Illusions, The Nickel City, Queen City of the Lakes, City of Light | |||

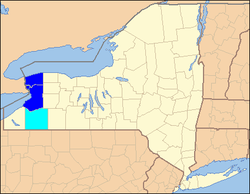

Location in Erie County and the state of New York. | |||

Buffalo, New York Location in the United States of America | |||

| Coordinates: 42°54′17″N 78°50′58″W / 42.90472°N 78.84944°WCoordinates: 42°54′17″N 78°50′58″W / 42.90472°N 78.84944°W | |||

| Country | United States | ||

| State | New York | ||

| County | Erie | ||

| First settled (village) | 1789 | ||

| Founded | 1801 | ||

| Incorporated (city) | 1832 | ||

| Government | |||

| • Mayor | Byron Brown (D) | ||

| • Common Council | City council | ||

| Area | |||

| • City | 52.5 sq mi (136.0 km2) | ||

| • Land | 40.6 sq mi (105.2 km2) | ||

| • Water | 11.9 sq mi (30.8 km2) | ||

| Elevation | 600 ft (183 m) | ||

| Population (2013) | |||

| • City | 258,959 (US: 73rd) | ||

| • Density | 6,436.2/sq mi (2,568.8/km2) | ||

| • Urban | 935,906 (US: 46th) | ||

| • Metro | 1,134,210 (US: 49th) | ||

| • CSA | 1,213,668 (US: 44th) | ||

| Demonym | Buffalonian | ||

| Time zone | EST (UTC−5) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | EDT (UTC−4) | ||

| ZIP code | 14200 | ||

| Area code(s) | 716 | ||

| FIPS code | 36-11000 | ||

| GNIS feature ID | 0973345 | ||

| Website | www.city-buffalo.com | ||

| [1][2] | |||

Buffalo /ˈbʌfəloʊ/ is a city in the U.S. state of New York and the seat of Erie County.[3] Located in Western New York on the eastern shores of Lake Erie and at the head of the Niagara River across from Fort Erie, Ontario, Canada, Buffalo is the principal city of the Buffalo-Niagara Falls metropolitan area, the largest in Upstate New York and 45th largest in the United States.[4] As of the 2010 U.S Census, the city proper had a population of 261,310, making the city the 69th largest city in the United States and the second most populous in the state after New York City.[5] The Buffalo–Niagara–Cattaraugus Combined Statistical Area is home to 1,215,826 residents.[6]

Originating around 1789 as a small trading community near the eponymous Buffalo Creek,[1] Buffalo grew quickly after the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825, with the city as its western terminus. By 1900, Buffalo was the 8th largest city in the United States,[7] and went on to become a major railroad hub,[8] and the largest grain-milling center in the country.[9] The latter part of the 20th century saw a reversal of fortunes: Great Lakes shipping was rerouted by the opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway, and steel mills and other heavy industry relocated to places such as China.[10] With the start of Amtrak in the 1970s, Buffalo Central Terminal was also abandoned, and trains were rerouted to nearby Depew, New York (Buffalo-Depew) and Exchange Street Station. By 1990, the city had fallen back below its 1960 population levels.[11]

Today, the region's largest economic sectors are financial services, technology,[12] health care and education,[13] and these continue to grow despite the lagging national and worldwide economies.[14] In recent years, expansions of the Buffalo Niagara Medical Campus[15] and the The State University of New York have led to private and public investment throughout the city and region.[16] A recent study found Buffalo's April 2014 unemployment rate to be 5.8%.[17] In 2010, Forbes rated Buffalo the 10th best place to raise a family in the United States.[18]

Residents of Buffalo are most commonly called "Buffalonians." Nicknames for the city of Buffalo include "The Queen City", Buffalo's most common moniker; "The Nickel City," due to the appearance of a bison on the back of Indian Head nickel in the early part of the 20th century, "The City of Good Neighbors," [19] and less commonly, the "City of Light."[20]

History

Prior to the Iroquois occupation of the region, the region was settled by the Neutral Nation. Later, the Senecas of the Iroquois Confederacy conquered the Neutrals and their territory, c. 1651.[21]

The city of Buffalo received its name from a nearby creek called Buffalo Creek. John Montresor references 'Buffalo Creek' in his journal of 1764.[22] There are several theories regarding how Buffalo Creek received its name.[23][24][25] While it is possible that the area was called "Buffalo" as a result of French fur traders and American Indians having called the creek "Beau Fleuve," or "Beautiful River," in French,[23][24] it is also possible that "Buffalo" was named for the bison as they did once roam Western New York.[25][26]

In 1804, Joseph Ellicott, a principal agent of the Holland Land Company, designed a radial street and grid system that branches out from downtown like bicycle spokes.[27]

During the War of 1812, on December 30, 1813,[28][29] Buffalo was burned by British forces.[30] On October 26, 1825,[31] the Erie Canal was completed with Buffalo a port-of-call for settlers heading westward.[32] At the time, the population was about 2,400.[33] The Erie Canal brought a surge in population and commerce which led Buffalo to incorporate as a city in 1832.[34]

Buffalo has long been home to African-Americans; an example is the 1828 village directory which listed 59 "names of coloured" heads of families.[35] In 1845, construction began on the Macedonia Baptist Church, commonly known as the Michigan Street Baptist Church.[36] This African-American church was an important meeting place for the abolitionist movement. On February 12, 1974, the church was added to the National Register of Historic Places.[35] Abolitionist leaders such as William Wells Brown made their home in Buffalo.[37] Buffalo was also a terminus point of the Underground Railroad[38] with many fugitives crossing the Niagara River from Buffalo to Fort Erie, Ontario in search of freedom.

During the 1840s, Buffalo's port continued to develop. Both passenger and commercial traffic expanded with some 93,000 passengers heading west from the port of Buffalo.[39] Grain and commercial goods shipments led to repeated expansion of the harbor. In 1843, the world's first steam-powered grain elevator was constructed by local merchant Joseph Dart and engineer Robert Dunbar.[40] The "Dart Elevator" enabled faster unloading of lake freighters along with the transshipment of grain in bulk from lakers to canal boats and, later on, rail cars.[39] By 1850, the population was 81,000.[34]

Abraham Lincoln visited Buffalo on February 16, 1861,[41] on his trip to accept the presidency of the United States. During his visit, he stayed at the American Hotel on Main Street between Eagle Street and Court Street.[42] In addition to sending many soldiers to the Union effort, Buffalo manufacturers supplied important war material. For example, the Niagara Steam Forge Works manufactured turret parts for the ironclad ship USS Monitor.[42] Between 1868 and 1896, building on Joseph Ellicott's spoke-and-hub urban blueprint and inspired by the parks and boulevards of Paris, France, Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux laid out Buffalo's public parks and parkways system, one of his largest works.[43][44]

Grover Cleveland served as Sheriff of Erie County (1871–1873),[45] and was Mayor of Buffalo in 1882. He was later Governor of New York (1883–1885), 22nd President of the United States (1885–1889) and 24th President (1893–1897).[46]

In May 1896, the Ellicott Square Building opened. For the next 16 years, it was the largest office building in the world. It was named after the surveyor Joseph Ellicott.[47][48]

At the dawn of the 20th century, local mills were among the first to benefit from hydroelectric power generated via the Niagara River. The city got the nickname City of Light at this time due to the widespread electric lighting.[20] It was also part of the automobile revolution, hosting the brass era car builders Pierce Arrow and the Seven Little Buffaloes early in the century.[49] City of Light (1999) was the title of Buffalo native Lauren Belfer's historical novel set in 1901, which in turn engendered a listing of real versus fictional persons and places[50] featured in her pages.

President William McKinley was shot and mortally wounded at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo on September 6, 1901.[51] He died in the city eight days later[52] and Theodore Roosevelt was sworn in at the Wilcox Mansion as the 26th President of the United States.[52]

An international bridge, known as the Peace Bridge, linking Buffalo to Fort Erie, Ontario, was opened on August 7, 1927,[53] The Buffalo Central Terminal, a 17-story Art Deco style station designed by architects Fellheimer & Wagner for the New York Central Railroad, opened in 1929.[54]

During World War II, Buffalo saw a period of prosperity and low unemployment due to its position as a manufacturing center.[55][56] The American Car and Foundry company, which manufactured railcars, reopened their Buffalo plant in 1940 to manufacture munitions during the war years.[57]

With the opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway in 1957, which cut the city off from valuable trade routes; deindustrialization; and the nationwide trend of suburbanization; the city's economy began to deteriorate.[58][59] Like much of the Rust Belt, Buffalo, home to more than half a million people in the 1950s, has seen its population decline as heavy industries shut down and people left for the suburbs or other cities.[58][59][60]

Like other rust belt cities such as Pittsburgh, Buffalo has attempted to revitalize its beleaguered economy and crumbling infrastructure. In the first decade of the 21st century, a massive increase in economic development spending has attempted to reverse its dwindling prosperity. $4 billion was spent in 2007 compared to a $50 million average for the previous ten years.[61] As of 2012, the population has continued to decrease, despite the efforts of city officials.[62]

In the early 2010s, new project proposals and renovations to historic buildings started to emerge, especially in the downtown core. Entrepreneurs, such as Buffalo Sabres owner Terrence Pegula, have helped with larger scale projects such as HarborCenter, a mixed-used complex near the Erie Canal Harbor. Other Buffalo-area developers have helped revitalize and repurpose abandoned buildings within the city, such as the Larkin Square project, and projects similar to this continue.[63]

Geography and climate

Buffalo is located on the eastern end of Lake Erie, opposite Fort Erie, Ontario, and at the beginning of the Niagara River, which flows northward over Niagara Falls and into Lake Ontario. The city is 50 miles (80 km) south-southeast from Toronto. Buffalo's position on Lake Erie, facing westward, makes it one of the only major cities on the East Coast to have sunsets over a body of water.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 52.5 square miles (136 km2), of which 40.6 square miles (105 km2) is land and 11.9 square miles (31 km2) is water. The total area is 22.66% water.

Cityscape

Architecture

The New York Times has declared that Buffalo is a city containing great American architecture from the 19th and 20th centuries.[64] Approximately 80 sites are included on the National Register of Historic Places. Most structures and works are still standing, such as the country's largest intact parks system designed by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux.[65] Buffalo was the first city for which Olmsted designed an interconnected park and parkway system rather than stand-alone parks.[66]

The Guaranty Building, a National Historic Landmark by Louis Sullivan, was one of the first steel-supported, curtain-walled buildings in the world. When the building was constructed, its 13 stories made it the tallest building in Buffalo and one of the world's first true skyscrapers.[67] The Hotel Buffalo, originally the Statler Hotel, by August Esenwein and James A. Johnson was the first hotel in the world to feature a private bath in each room. The Richardson Olmstead Complex, originally the New York State Asylum for the Insane, is Richardsonian Romanesque in style and was designed by prominent architect Henry Hobson Richardson, while the grounds of the hospital were designed by Olmsted. Though the complex is currently in a state of disrepair, New York State has allocated funds to restore the complex.[68]

There are several buildings by Frank Lloyd Wright, including the Darwin D. Martin House, George Barton House, William R. Heath House, Walter V. Davidson House, The Graycliff Estate, as well as the now demolished Larkin Administration Building.[69][70] Constructed in 2007 on Buffalo's Black Rock Canal is a Wright-designed boathouse originally intended, but never built, for the University of Wisconsin–Madison rowing team.[71] Along as a tourist destination, it functionally serves many Buffalo-area rowing teams belonging to the West Side Rowing Club. The Buffalo City Hall building by George Dietel and John J. Wade is a large Art deco skyscraper listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

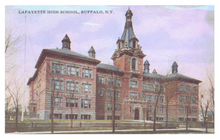

Other notable buildings include Buffalo Central Terminal, a massive Art Deco railroad station designed by Alfred T. Fellheimer and Steward Wagner, Lafayette High School, a stone, brick and terra-cotta structure in the French Renaissance Revival style by architects August Eisenwein and James A. Johnson, is the oldest public school in Buffalo that remains in its original building, and is on the National Register of Historic Places, St. Adalbert's Basilica, St. Stanislaus, Bishop and Martyr Church, Corpus Christi, St. Paul's Episcopal, Kleinhans Music Hall, Temple Beth Zion,[72] and Lions for the McKinley Monument. Grain elevators were invented along the Buffalo River in 1842, and the city maintains one of the largest standing collection in the world.

Neighborhoods

Buffalo consists of 32 different neighborhoods, including Allentown, Black Rock, Broadway-Fillmore, Central Park, Cold Springs, Delaware District, Downtown, East Side, Elmwood Village, Fillmore-Leroy, First Ward, Fruit Belt, Hamlin Park, Hospital Hill, Humboldt Park, Kaisertown, Kensington, Kensington Heights, Lovejoy, Lower West Side, Masten Park, North Buffalo, North Park, Park Meadow, Parkside, Riverside, Schiller Park, South Buffalo, University District, University Heights, Vernon Triangle, Upper West Side, and Willert Park.[73]

The American Planning Association named the Elmwood Village neighborhood in Buffalo one of ten Great Neighborhoods in 2007.[74] Elmwood Village[75] is a pedestrian-oriented, mixed use neighborhood with hundreds of small, locally owned boutiques, shops, restaurants, and cafes. The neighborhood is located to the south of Buffalo State College.

The Seneca Babcock neighborhood, which was split by the construction of Interstate 190 during the 1950s, is troubled by the presence of a concrete crushing facility which is grandfathered in as a pre-existing use, while dust and truck traffic from the facility strongly impact residences in the neighborhood.[76]

There are currently nine common council districts within Buffalo, including the Delaware, Ellicott, Fillmore, Lovejoy, Masten, Niagara, North, South, and University districts.[77]

Climate

The Buffalo area experiences a fairly humid, continental-type climate, but with a definite maritime flavor due to strong modification from the Great Lakes (Köppen climate classification "Dfb" – uniform precipitation distribution). The transitional seasons are very brief in Buffalo and Western New York.

Buffalo has a reputation for snowy winters, but it is rarely the snowiest city in New York State.[78][79] Winters in Western New York are generally cold and snowy, but are changeable and include frequent thaws and rain as well. Snow covers the ground more often than not from late December into early March, but periods of bare ground are not uncommon. Over half of the annual snowfall comes from the lake effect process and is very localized. Lake effect snow occurs when cold air crosses the relatively warm lake waters and becomes saturated, creating clouds and precipitation downwind. Due to the prevailing winds, areas south of Buffalo receive much more lake effect snow than locations to the north. The lake's "snow machine" starts as early as mid-November, peaks in December, then virtually shuts down after Lake Erie freezes in mid-to-late January. The most well-known snowstorm in Buffalo's history, the Blizzard of 1977, was not a lake effect snowstorm in Buffalo in the normal sense of that term (Lake Erie was frozen over at the time), but instead resulted from a combination of high winds and snow previously accumulated both on land and on frozen Lake Erie. Snow does not typically impair the city's operation, but can cause significant damage during the autumn as with the October 2006 storm, colloquially known as the "October Surprise."[80][81] In November 2014 the region experienced a record-breaking storm with thundersnow which killed at least eight people, flattened roofs and dumped over 6 feet (1.8 m) of snow in some locations—stranding motorists, triggering a driving ban and forcing a change in venue for a scheduled football game between the Buffalo Bills and the New York Jets.[82][83] By November 21, the estimated death toll had increased to 12 and flooding was reported as a major concern with reports of an impending warm-up. If forecast totals hold, the storm will have produced more snow in three days the area typically experiences in a single year.[84]

Buffalo has the sunniest and driest summers of any major city in the Northeast, but still has enough rain to keep vegetation green and lush.[85] Summers are marked by plentiful sunshine and moderate humidity and temperature. It receives, on average, over 65% of possible sunshine in June, July and August. Obscured by the notoriety of Buffalo's winter snow is the fact that Buffalo benefits from other lake effects such as the cooling southwest breezes off Lake Erie in summer that gently temper the warmest days. As a result, the Buffalo station of the National Weather Service has never recorded an official temperature of 100 °F (37.8 °C) or more.[86] Rainfall is moderate but typically occurs at night. The stabilizing effect of Lake Erie continues to inhibit thunderstorms and enhance sunshine in the immediate Buffalo area through most of July. August usually has more showers and is hotter and more humid as the warmer lake loses its temperature-stabilizing influence.

The highest recorded temperature in Buffalo was 99 °F (37 °C) on August 27, 1948,[87] and the lowest recorded temperature was −20 °F (−29 °C) on February 9, 1934 and February 2, 1961.[88]

| Climate data for Buffalo, New York (Buffalo Niagara Int'l), 1981–2010 normals, extremes 1871–present[lower-alpha 1] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 72 (22) |

71 (22) |

82 (28) |

94 (34) |

94 (34) |

97 (36) |

97 (36) |

99 (37) |

98 (37) |

92 (33) |

80 (27) |

74 (23) |

99 (37) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 31.2 (−0.4) |

33.3 (0.7) |

42.0 (5.6) |

55.0 (12.8) |

66.5 (19.2) |

75.3 (24.1) |

79.9 (26.6) |

78.4 (25.8) |

71.1 (21.7) |

59.0 (15) |

47.6 (8.7) |

36.1 (2.3) |

56.3 (13.5) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 18.5 (−7.5) |

19.2 (−7.1) |

26.0 (−3.3) |

36.8 (2.7) |

47.4 (8.6) |

57.3 (14.1) |

62.3 (16.8) |

60.8 (16) |

53.4 (11.9) |

42.7 (5.9) |

33.9 (1.1) |

24.1 (−4.4) |

40.2 (4.6) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −16 (−27) |

−20 (−29) |

−7 (−22) |

5 (−15) |

25 (−4) |

35 (2) |

43 (6) |

38 (3) |

32 (0) |

20 (−7) |

2 (−17) |

−10 (−23) |

−20 (−29) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.18 (80.8) |

2.49 (63.2) |

2.87 (72.9) |

3.01 (76.5) |

3.46 (87.9) |

3.66 (93) |

3.23 (82) |

3.26 (82.8) |

3.90 (99.1) |

3.52 (89.4) |

4.01 (101.9) |

3.89 (98.8) |

40.48 (1,028.2) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 25.3 (64.3) |

17.3 (43.9) |

12.9 (32.8) |

2.7 (6.9) |

0.3 (0.8) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.9 (2.3) |

7.9 (20.1) |

27.4 (69.6) |

94.7 (240.5) |

| Avg. precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 19.2 | 16.0 | 15.1 | 13.1 | 12.7 | 12.1 | 10.6 | 10.1 | 11.4 | 12.9 | 15.0 | 18.3 | 166.5 |

| Avg. snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 16.3 | 13.1 | 9.2 | 3.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.4 | 4.9 | 14.0 | 61.0 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 76.0 | 75.9 | 73.3 | 67.8 | 67.2 | 68.6 | 68.1 | 72.1 | 74.0 | 72.9 | 75.8 | 77.6 | 72.4 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 91.3 | 108.0 | 163.7 | 204.7 | 258.3 | 287.1 | 306.7 | 266.4 | 207.6 | 159.4 | 84.4 | 69.0 | 2,206.6 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 31 | 37 | 44 | 51 | 57 | 63 | 66 | 62 | 55 | 47 | 29 | 25 | 49 |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity and sun 1961–1990)[89][90][91], Weather Channel[92] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1810 | 1,508 | — | |

| 1820 | 2,095 | 38.9% | |

| 1830 | 8,668 | 313.7% | |

| 1840 | 18,213 | 110.1% | |

| 1850 | 42,261 | 132.0% | |

| 1860 | 81,129 | 92.0% | |

| 1870 | 117,714 | 45.1% | |

| 1880 | 155,134 | 31.8% | |

| 1890 | 255,664 | 64.8% | |

| 1900 | 352,387 | 37.8% | |

| 1910 | 423,715 | 20.2% | |

| 1920 | 506,775 | 19.6% | |

| 1930 | 573,076 | 13.1% | |

| 1940 | 575,901 | 0.5% | |

| 1950 | 580,132 | 0.7% | |

| 1960 | 532,759 | −8.2% | |

| 1970 | 462,768 | −13.1% | |

| 1980 | 357,870 | −22.7% | |

| 1990 | 328,123 | −8.3% | |

| 2000 | 292,648 | −10.8% | |

| 2010 | 261,310 | −10.7% | |

| Est. 2013 | 258,959 | −0.9% | |

| Historical Population Figures[93] U.S. Decennial Census[94] 2013 Estimate[95] | |||

| Racial composition | 2010[96] | 1990[97] | 1970[97] | 1940[97] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 50.4% | 64.7% | 78.7% | 96.8% |

| —Non-Hispanic | 45.8% | 63.1% | 77.4%[98] | 96.8% |

| Black or African American | 38.6% | 30.7% | 20.4% | 3.1% |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 10.5% | 4.9% | 1.6%[98] | (X) |

| Asian | 3.2% | 1.0% | 0.2% | − |

Like most formerly industrial cities of the Great Lakes region in the United States, Buffalo is recovering from an economic depression brought about by suburbanization and the loss of its industrial base. The city's population peaked in 1950, when it was the 15th largest city in the United States, and its population has been spreading out to the suburbs every census since then. The demographic change and the impact of such change on the industrial cities of the region, including Buffalo, was significant; based on the 2006 US Census estimate, Buffalo's current population was equivalent to its population in the year 1890, reversing 120 years of demographic change. On the other hand, the populations of surrounding suburbs such as Amherst, Clarence, Orchard Park, Cheektowaga, etc. have increased proportionally as automobile-centric lifestyles developed.

At the 2010 Census, the city's population was 50.4% White (45.8% non-Hispanic White alone), 38.6% Black or African-American, 0.8% American Indian and Alaska Native, 3.2% Asian, 3.9% from some other race and 3.1% from two or more races. 10.5% of the total population was Hispanic or Latino of any race.[99]

At the time of the 2000 census there were 292,648 people, 122,720 households, and 67,005 families residing in the city. The population density is 7,205.8 people per square mile (2,782.4/km2). There are 145,574 housing units at an average density of 3,584.4 per square mile (1,384.1/km2). The racial makeup of the city is 54.43% White, 37.23% African-American, 0.77% Native American, 1.40% Asian, 0.04% Pacific Islander, 3.68% from other races, and 2.45% from two or more races. 7.54% of the population are Hispanic or Latino of any race. The top 5 largest ancestries include German (13.6%), Irish (12.2%), Italian (11.7%), Polish (11.7%), and English (4.0%).[100]

There were 122,720 households out of which 28.6% have children under the age of 18 living with them, 27.6% are married couples living together, 22.3% have a female householder with no husband present, and 45.4% are non-families. 37.7% of all households are made up of individuals and 12.1% have someone living alone who is 65 years of age or older. The average household size is 2.29 and the average family size is 3.07.

In the city the population included 26.3% under the age of 18, 11.3% from 18 to 24, 29.3% from 25 to 44, 19.6% from 45 to 64, and 13.4% who are 65 years of age or older. The median age is 34 years. For every 100 females there are 88.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there are 83.5 males.

The median income for a household in the city is $24,536, and the median income for a family is $30,614. Males have a median income of $30,938 versus $23,982 for females. The per capita income for the city is $14,991. 26.6% of the population and 23.0% of families are below the poverty line. Out of the total population, 38.4% of those under the age of 18 and 14.0% of those 65 and older are living below the poverty line.

Buffalo has very sizable populations of Irish, Italian, Polish, German, Jewish, Greek, Arab, African-American, Indian, Macedonian, and Puerto Rican descent. Major ethnic neighborhoods still exist but they changed significantly in the second half of the 20th century. In 1940, non-Hispanic Whites were 96.8% of the city's population.[97] Traditionally, Polish-Americans were the predominant occupants of the East Side, while Italian-Americans composed a close-knit neighborhood in the west side. The East Side is now a predominantly African-American neighborhood, while the West Side has become a melting pot of many ethnicities, with Latino culture being the strongest influence. Throughout the history of Buffalo, the neighborhoods collectively called the First Ward, as well as much of South Buffalo, have comprised almost entirely people of Irish descent. Recently, there has been an influx of inhabitants that are of Arab descent, mainly from Yemen, as the city's Muslim population has increased to approximately 3,000 according to an estimate.[101] Since the 1950s and 1960s, the greater portion of the Jewish population has moved to the suburban areas outside of the city, or to the city's upper West Side.

In a 2008 United Nations report entitled State of the World's Cities, figures from the Buffalo-Niagara Falls metropolitan area were used to show economic and racial inequality throughout the world. The report stated that 40% of African-American, Hispanic and ethnically mixed homes earned less that $15,999, when compared to 15% of White homes.[102] The United States Census Department also released information placing the Buffalo-Niagara metro area as the eighth-most segregated area in the United States.[103]

Economy

Historically, Buffalo's economy was fostered by its position at the eastern end of Lake Erie and as the western terminus on the Erie Canal. These factors contributed to later growth in the areas of grain and steel, which were major commodities for the city. Today, the economy of Buffalo consists of a mix of industrial, light manufacturing, high technology and service-oriented private sector companies. Instead of relying on a single industry or sector for its economic future, the region has taken a diversified approach that have the potential to create opportunities for growth and expansion in the 21st century.[104]

The State of New York, with over 15,000 employees, is the city's largest employer.[105] Other major employers within the city include the United States government, Kaleida Health, M&T Bank, the University at Buffalo, and Tops Friendly Markets.

Overall, employment in Buffalo has shifted as its population has declined and manufacturing has left. Buffalo's 2005 unemployment rate was 6.6%, contrasted with New York State's 5.0% rate.[106] From the fourth quarter of 2005 to the fourth quarter of 2006, Erie County had no net job growth, ranking it 271st among the 326 largest counties in the country.[107] However, the area has recently seen an upswing in job growth as unemployment has dropped to only 4.9% in July 2007 from 5.2% in 2006 and 6.6% in 2005.[108] The area's manufacturing jobs have continued to show the largest losses in jobs with over 17,000 fewer than at the start of 2006. Yet other sectors of the economy have outdistanced manufacturing and are seeing large increases. Educational and health services added over 30,400 jobs in 2006 and over 20,500 jobs have been added in the professional and business (mostly finance) arena.[109]

In banking, Buffalo is the headquarters of M&T Bank and First Niagara Bank. HSBC Bank USA, which had a major presence in the Buffalo area and was formerly headquartered in One Seneca Center has reduced its local operations in Buffalo and upstate New York as it closed its retail banking centers. Other banks, such as Bank of America and KeyBank have corporate operations in Buffalo. Citigroup also has regional offices in Amherst, Buffalo's largest suburb. The city has also become a hub of the debt collection industry.[110]

Buffalo is also home to Rich Products, Canadian brewer Labatt, cheese company Sorrento Lactalis, Delaware North Companies[111] and New Era Cap Company. A Del Monte Foods Milk Bone manufacturing center is on Buffalo's East Side.[112]

The loss of traditional jobs in manufacturing, rapid suburbanization and high costs of labor have led to economic decline, making Buffalo one of the poorest among major U.S. cities with populations of more than 250,000 people. An estimated 28.7–29.9% of Buffalo residents live below the poverty line, behind either only Detroit,[113] or only Detroit and Cleveland.[114] Buffalo's median household income of $27,850 is third-lowest among large cities, behind only Miami and Cleveland; however the median household income for the metropolitan area is $57,000.[115] This, in part, has led to the Buffalo-Niagara Falls metropolitan area having the most affordable housing market in the U.S. today. The quarterly NAHB/Wells Fargo Housing Opportunity Index (HOI) noted that nearly 90% of the new and existing homes sold in the metropolitan area during the second quarter were affordable to families making the area's median income of $57,000. As of 2014, the median home price in the city was $95,000.[116]

Between 2000 and 2007, the city demolished 2,000 vacant homes, but as many as 10,000 still remained. In 2007, Mayor Byron W. Brown unveiled a $100 million, five-year plan to demolish 5,000 additional vacant houses.[117]

In July 2005, Reader's Digest ranked Buffalo as the third cleanest large city in the nation.[118]

Buffalo's economy has begun to see significant improvements since the early 2010s.[119] Money from New York State Governor Andrew Cuomo through a program known locally as "Buffalo Billion" has allowed plans for different construction programs to proceed, an increase in economic development, and hundreds of new jobs bringing strong economic change to the area.[120] As of March 2015, the unemployment rate for Buffalo was 5.9%,[121] slightly above the national average of 5.5%.[122]

Culture

Cuisine

As a melting pot of cultures, cuisine in the Buffalo area reflects a variety of influences. These include Italian, Irish, Jewish, German, Polish, African-American, Greek, Indian and American influences.

As a result of the recent cultural re-birth, over 50 new locally owned restaurants have opened in downtown Buffalo over the past 2 years, including the Lodge, Tappo, 716 Food and Sport, Liberty Hound, Pan American Grill, Bourbon and Butter, Oshun, Bada Bing, Dinosaur BBQ, Buffalo Proper, Cantina Loco, Allentown Burger Venture (ABV), and Handlebar. Chain-style fast food with a notable local presence include Ted's Hot Dogs, SPoT Coffee, Tim Hortons, and Mighty Taco. More traditional, old-Buffalo style, local restaurants include Louie's Hot Dogs, La Nova Pizzeria, Anderson's Frozen Custard, John and Mary's Submarines, Duff's Famous Wings, Jim's Steakout, and Just Pizza.

The Elmwood Village district is home to many highly rated restaurants, pubs, and cafés. The Village is also home to the Lexington Co-Operative market, a local distributor, co-op market of organic food products.

Buffalo's local pizzerias differs from that of the thin-crust New York-style pizzerias and deep-dish Chicago-style pizzerias, and is locally known for being a midpoint between the two.[123]

The city is home to the Pearl Street Brewery and Flying Bison Brewing Company, who continue the city's brewing traditions.

Buffalo has several specialty import/grocery stores in old ethnic neighborhoods, and is home to an eclectic collection of cafes and restaurants that serve adventurous, cosmopolitan fare. Locally owned restaurants offer Chinese, German, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, Thai, Mexican, Italian, Arab, Indian, Caribbean, soul food, and French.[124][125]

Several well-known food companies are based in Buffalo. Non-dairy whipped topping was invented in Buffalo in 1945 by Robert E. Rich, Sr.[126] His company, Rich Products, is one of the city's largest private employers.[127] General Mills was organized in Buffalo, and Gold Medal brand flour, Wheaties, Cheerios and other General Mills brand cereals are manufactured here. Archer Daniels Midland operates its largest flour mill in the city.[128] Buffalo is home to one of the largest privately held food companies in the world, Delaware North Companies, which operates concessions in sports arenas, stadiums, resorts, and many state & federal parks.[129] Beef on weck sandwich, Wardynski's kielbasa, sponge candy, pastry hearts, pierogi, and haddock fish fries are among the local favorites, as is a loganberry-flavored beverage that remains relatively obscure outside of the Western New York and Southern Ontario area.[130]

Another uniquely Buffalonian food is Sahlen's "charcoal-broiled" hot dogs, which are prepared over live charcoal fires. The typical boiled or steamed "franks" of other cities are considered inferior by native Buffalonians.

Weber's is a local producer of horseradish mustard, which is popular in the Western New York area.

Teressa Bellissimo first prepared the now widespread Buffalo wing at the Anchor Bar on October 3, 1964.[131]

Fine and performing arts

Buffalo is home to over 50 private and public art galleries,[132] most notably the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, home to a world-class collection of modern and contemporary art. The local art scene is also enhanced by the Burchfield-Penney Art Center, Hallwalls Contemporary Arts Center, CEPA Gallery, and many small galleries and studios.[133][134] In 2012, AmericanStyle ranked Buffalo twenty-fifth in its list of top mid-sized cities for art.[135]

The Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra, which performs at Kleinhans Music Hall, is one of the city's most prominent performing arts institutions. During the 1960s and 1970s, under the musical leadership of Lukas Foss and Michael Tilson Thomas, the Philharmonic collaborated with Grateful Dead and toured with the Boston Pops Orchestra.[136] The largest theatre in the Buffalo area is Shea's Performing Arts Center, designed for 4,000 people by Louis Comfort Tiffany. Long known as "Shea's Buffalo" and constructed in 1926, the theatre continues to show productions and concerts.

The theatre community in the Buffalo Theater District includes over 20 professional companies.[137][138][139] Major theatres groups include The Alt at the Warehouse, American Repertory Theater of Western New York, The Irish Classical Theatre, The Kavinoky Theatre, Lancaster Opera House, The New Phoenix Theatre, Road Less Traveled Productions, The Subversive Theatre, The Theatre of Youth, and Torn Space Theatre. These companies present a variety of theatre styles and many present original productions by Buffalo playwrights.

Buffalo is also home one of the largest free outdoor Shakespeare festival in the United States, Shakespeare in Delaware Park. Filmmaker, writer, painter and musician Vincent Gallo was born in Buffalo in 1962 and lived there until 1978 when he moved out on his own to New York City.

Music

Buffalo has the roots of many jazz and classical musicians, and it is also the founding city for several mainstream bands and musicians, including Rick James, Billy Sheehan, The Quakes and The Goo Goo Dolls. Vincent Gallo, a Buffalo-born filmmaker and musician, played in several local bands. Jazz fusion band Spyro Gyra also got its start in Buffalo.[140] The great American classical Pianist and composer Leonard Pennario was born in Buffalo in 1924 and made his debut concert at Carnegie Hall in 1943. Among notable Buffalo-born jazz musicians are saxophonists Grover Washington Jr, Don Menza, Larry Covelli, Bobby Militello, trumpeter Sam Noto, and guitarist Jim Hall. Buffalo also became the adopted home other jazz musicians such as clarinetist Hank D'Amico, saxophonist Elvin Shepard and pianist Al Tinney.

Buffalo's "Colored Musicians Club", an extension of what was long-ago a separate musicians' union local, is thriving today, and maintains a significant jazz history within its walls. Well-known indie artist Ani DiFranco hails from Buffalo, and it is the home of her "Righteous Babe" record label.

10,000 Maniacs are from nearby Jamestown, but got their start in Buffalo, which led to lead singer Natalie Merchant launching a successful solo career.

Death Metal band Cannibal Corpse reached national fame in 1994 when they appeared in the movie Ace Ventura: Pet Detective, at the request of lead actor Jim Carrey.[141] The director agreed and decided to actually have Jim jump on stage with the band and perform "Hammer Smashed Face" in the film to escape two pursuing goons.[141]

Festivals

Like many large cities, numerous festivals have become part of the city's culture and tradition. Though most of the festivals occur during the summer months, the city has recently pushed efforts to have winter festivals as well in an effort to capitalize on the region's snowy reputation. Popular summer festivals include the Allentown Art Festival, Taste of Buffalo, National Buffalo Wing Festival, Thursday at the Square, and the Juneteenth Festival. Winter festivals include the Buffalo Ball Drop,[142] Buffalo Powder Keg Festival,[143] and Labatt Blue Pond Hockey.[144]

Tourism

Points of interest in the city of Buffalo include the Edward M. Cotter fireboat, considered to be the world's oldest active fireboat[145] and is a United States National Historic Landmark, Buffalo and Erie County Botanical Gardens, the Buffalo and Erie County Historical Society,[146] Buffalo Museum of Science,[147] the Buffalo Zoo, the third oldest zoo in the United States,[148] Forest Lawn Cemetery, Buffalo and Erie County Naval & Military Park, the Anchor Bar, and Lafayette Square.

Sports

Buffalo and the surrounding region is home to two major league professional sports teams. The Buffalo Sabres of the NHL play in the City of Buffalo, and the Buffalo Bills of the NFL play in the suburb of Orchard Park, New York. Buffalo is also home to several minor sports teams including the Buffalo Bisons (baseball), Buffalo Bandits (indoor lacrosse) and FC Buffalo (soccer). Several Buffalo-area colleges and universities are active in college athletics.

The Buffalo Bills, established in 1959, played in War Memorial Stadium until 1973, when Ralph Wilson Stadium was constructed. The team competes in the AFC East division. Since the AFL–NFL merger in 1970, the Bills have won the division title seven times (1980, 1988, 1989, 1990, 1991, 1993, 1995), and the AFC conference championship four consecutive times (1990, 1991, 1992, 1993), resulting in four lost Super Bowls.

The Buffalo Sabres, established in 1970, played in War Memorial Auditorium until 1996, when Marine Midland Arena, now First Niagara Center, opened. The team is within the Atlantic Division of the NHL. The team has won six division titles, one Presidents' Trophy (2006–07) and three conference championships (1974–75, 1979–80, 1998–99). However, like the Buffalo Bills, the team does not have a league championship.

The Buffalo Bandits, established in 1992, played home games in War Memorial Auditorium until their move to Marine Midland Arena. They have won eight division championships and four league championships (1992, 1993, 1996, 2008).

| Sport | League | Club | Founded | Venue | Titles | Championship years |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Football | NFL | Buffalo Bills | 1960 | Ralph Wilson Stadium | 2* | 1964, 1965* |

| Hockey | NHL | Buffalo Sabres | 1970 | First Niagara Center | 0 | |

| Baseball | IL | Buffalo Bisons | 1979† | Coca-Cola Field | 3 | 1997, 1998, 2004 |

| Lacrosse | NLL | Buffalo Bandits | 1992 | First Niagara Center | 4 | 1992, 1993, 1996, 2008 |

| Soccer | NPSL | FC Buffalo | 2009 | Demske Sports Complex | 0 | |

| Basketball | PBL | Buffalo 716ers | 2012 | Tapestry Charter School | 0 |

* Championships listed are American Football League championships, not NFL championships.

† Date refers to current incarnation; Buffalo Bisons previously operated from the 1870s until 1970 and the current Bisons count this team as part of their history.

Parks and recreation

The Buffalo parks system contains over 20 parks with multiple parks accessible from any part of the city. The Olmsted Park and Parkway System is the hallmark of Buffalo's many green spaces. Three-fourths of city park land is part of the system, which comprises six major parks, eight connecting parkways, nine circles and seven smaller spaces. Constructed in 1868 by Frederick Law Olmsted and his partner Calvert Vaux, the system was integrated into the city and marks the first attempt in America to lay out a coordinated system of public parks and parkways. The Olmsted designed portions of the Buffalo park system are listed on the National Register of Historic Places and are maintained by the Buffalo Olmsted Parks Conservancy.

Situated at the confluence of Lake Erie and the Buffalo River and Niagara Rivers, Buffalo is a waterfront city. The city's rise to economic power came through its waterways in the form of transshipment, manufacturing, and an endless source of energy. Buffalo's waterfront remains, though to a lesser degree, a hub of commerce, trade, and industry.

As of 2009, a significant portion of Buffalo's waterfront is being transformed into a focal point for social and recreational activity. To this end, Buffalo Harbor State Park was opened on Buffalo's outer harbor in 2014.[149] Buffalo's intent is to stress its architectural and historical heritage, creating a tourism destination.

An ongoing project within downtown Buffalo is the development of "Canalside," intended to revitalize the original Erie Canal Harbor with shops, eateries, and tourist attractions. An early phase of the project was the excavation and filling of Erie Canal Commercial Slip, which is the original western terminus of the Erie Canal System. Currently, work is underway to restore the canal system which was displaced by the construction of the Buffalo Memorial Auditorium.

Government

At the municipal level, the City of Buffalo has a mayor and a council consisting of nine councilmembers. Buffalo also serves as the seat of Erie County with some of the 11 members of county legislature representing at least a portion of Buffalo. At the state level, there are three state assemblymembers and two state senators representing parts of the city proper. At the federal level, Buffalo is represented by three members of the House of Representatives.

In a trend common to Northern "Rust Belt" regions, political life in Buffalo has been dominated by the Democratic Party for the last half-century, and has been roiled by racial division and social issues. The last time anyone other than a Democrat held the position of Mayor in Buffalo was Chester A. Kowal in 1965. In 1977, Democratic Mayor James D. Griffin was first elected as the nominee of two minor parties, the Conservative Party and the Right to Life Party, after he lost the Democratic primary for Mayor to then Deputy State Assembly Speaker Arthur Eve. Griffin switched political allegiance several times during his 16 years as Mayor, generally hewing to socially conservative platforms. His successor, Democrat Anthony M. Masiello (elected in 1993) continued to campaign on social conservatism, often crossing party lines in his endorsements and alliances. In 2005, however, Democrat Byron Brown was elected the city's first African-American mayor in a landslide (64%–27%) over Republican Kevin Helfer, who ran on a conservative platform. In 2013, Brown would be endorsed by the Conservative Party because of his pledge to cut taxes.

This change in local politics was preceded by a fiscal crisis in 2003 when years of economic decline, a diminishing tax-base, and civic mismanagement left the city deep in debt and teetering on the edge of bankruptcy. At the urging of New York State Comptroller Alan Hevesi, the state took over the management of Buffalo's finances, appointing the Buffalo Fiscal Stability Authority. Conversations about merging the city with the larger Erie County government were initiated the following year by Mayor Tony Masiello, but came to naught.

The offices of the Buffalo District, US Army Corps of Engineers are located adjacent to the Black Rock Lock in the Black Rock channel of the Erie Canal. In addition to maintaining and operating the lock, the District is responsible for planning, design, construction and maintenance of water resources projects in an area extending from Toledo, Ohio to Massena, New York. These include the flood-control dam at Mount Morris, New York, oversight of the lower Great Lakes (Lake Erie and Lake Ontario), review and permitting of wetlands construction, and remedial action for hazardous waste sites.

Buffalo is also the home of a major office of the National Weather Service (NOAA), which serves all of western and much of central New York State.

Buffalo is home to one of the 56 national FBI field offices. The field office covers all of Western New York and parts of the Southern Tier and Central New York. The field office operates several task forces in conjunction with local agencies to help combat issues such as gang violence, terrorism threats and health care fraud.[150]

Buffalo is also the location of the chief judge, United States Attorney, and administrative offices for the United States District Court for the Western District of New York.

Education

Buffalo Public Schools serves most of the city of Buffalo. Currently, there are 78 public schools in the city including a growing number of charter schools. As of 2006, the total enrollment was 41,089 students with a student-teacher ratio of 13.5 to 1. The graduation rate is up to 52% in 2008, up from 45% in 2007, and 50% in 2006.[151] More than 27% of teachers have a Master's degree or higher and the median amount of experience in the field is 15 years. When considering the entire metropolitan area, there are a total of 292 schools educating 172,854 students.[152] Buffalo has a magnet school system, featuring schools that attract students with special interests, such as science, bilingual studies, and Native American studies. Specialized facilities include the Buffalo Elementary School of Technology; the Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Multicultural Institute; the International School; the Dr. Charles R. Drew Science Magnet; BUILD Academy; Leonardo da Vinci High School; PS 32 Bennett Park Montessori; the Buffalo Academy for Visual and Performing Arts, BAVPA; the Riverside Institute of Technology; Lafayette High School/Buffalo Academy of Finance; Hutchinson Central Technical High School; Burgard Vocational High School; South Park High School; and the Emerson School of Hospitality.

The city is home to 47 private schools while the metropolitan region has 150 institutions. Most private schools have a Roman Catholic affiliation. There are schools affiliated with other religions such as Islam. There are also nonsectarian options including The Buffalo Seminary (the only private, nonsectarian, all-girls school in Western New York state),[153] and Nichols School.

Complementing its standard function, the Buffalo Public Schools Adult and Continuing Education Division provides education and services to adults throughout the community.[154] In addition, the Career and Technical Education Department offers more than 20 academic programs, and is attended by about 6,000 students each year.[155] The city is also served by four Catholic schools including Bishop Timon - St. Jude High School, Canisius High School, Mount Mercy Academy, and Nardin Academy. In addition, there are two Islamic schools including Darul Uloom Al-Madania and Universal School of Buffalo.

Buffalo is home to three State University of New York (SUNY) institutions. The University at Buffalo and Buffalo State College are the largest institutions of their type in the system. The total enrollment of these 3 SUNY institutions combined is approximately 54,000 students in the area. In addition, the region is served by Erie Community College.

The Buffalo and Erie County Public Library maintains multiple branches across the city of Buffalo and Erie County, as well as maintaining the main building.

Infrastructure

Healthcare

Buffalo has increasingly become a center for bioinformatics and human genome research, including work by researchers at the University at Buffalo and the Roswell Park Cancer Institute, through a consortium known as the Buffalo Niagara Medical Campus.

Transportation

Airports

The Niagara Frontier Transportation Authority (NFTA) operates Buffalo Niagara International Airport and Niagara Falls International Airport, however Buffalo is primarily served by the Buffalo Niagara International Airport, located in the nearby suburb of Cheektowaga. The airport, reconstructed in 1997, serves over 5 million passengers per year and growing. Buffalo Niagara International Airport ranks among the five cheapest airports from which to fly in the country, according to the U.S. Bureau of Transportation Statistics. The average round trip flight cost is $295.58.[156] In the last few years there has been a surge in Canadians flying out of Buffalo, mainly due to much cheaper tax and airline surcharges, as compared with Canadian airports and the ability to fly on some US based discount carriers not available in Canada (for example, JetBlue Airways and Southwest Airlines). As of 2006, plans are in the works by U.S. Senator Charles Schumer to make the under-used Niagara Falls International Airport into an international cargo hub for New York and Toronto, as well as Canada as a whole.[157]

Public transit

The Buffalo Metro Rail, also operated by the NFTA, is a 6.4 miles (10.3 km) long, single line light rail system that extends from Erie Canal Harbor in downtown Buffalo to the University Heights district (specifically, the South Campus of University at Buffalo) in the northeastern part of the city. The downtown section of the line runs above ground and is free of charge to passengers. North of Theater Station, at the northern end of downtown, the line moves underground, remaining underground until it reaches the northern terminus of the line at University Heights. Passengers pay a fare to ride this section of the rail.

A NFTA project underway, "Cars Sharing Main Street" will substantially revise the downtown portion of the Metro Rail. It will allow vehicular traffic and Metro Rail cars to share Main St. in a manner similar to that of the trolleys of San Francisco. The design includes new stations and pedestrian-friendly improvements. The first phase of the project, restoring two way traffic on Main Street between Edward and West Tupper, was completed in 2009.

The NFTA operates bus lines throughout the city, region and suburbs.

Railroads

Two train stations, Buffalo-Depew and Buffalo-Exchange Street serve the city and are operated by Amtrak. Historically the city was a major stop on through routes between Chicago and New York City through the lower Ontario peninsula.[158] Additionally, the Pennsylvania Railroad ran trains between Buffalo and Washington, D.C. on the Buffalo Line through central Pennsylvania.[159]

Historically, New York Central trains went through the Buffalo Central Terminal, Lackawanna trains went through its terminal on Main Street until the mid-1950s and the Lehigh Valley Railroad's trains went through its terminal until 1952. From 1935 the Erie Railroad used the Lehigh Valley facility.[160][161]

Freight service for Buffalo is served by CSX Transportation and Norfolk Southern (NS), as well as Canadian National (CN) and Canadian Pacific (CP) railroads from across the Border. The area has 4 large rail yards: Frontier (CSX), Bison (NS), SK (NS / CP) and Buffalo Creek (NS / CSX). A large amount of hazardous cargo also crosses through the Buffalo area, such as liquid propane and anhydrous ammonia.

Waterways

Buffalo is at the eastern end of one of the Great Lakes, Lake Erie, which boasts the greatest variety of freshwater sportfish in the country. The Lake serves as a playground for numerous personal yachts, sailboats, power boats and watercraft. The city has an extensive breakwall system protecting its inner and outer Lake Erie harbors, which are maintained at commercial navigation depths for Great Lakes freighters.

A Lake Erie tributary that flows through south Buffalo is the Buffalo River and Buffalo Creek. Buffalo is historically linked to the fabled Erie Canal, which ends where the Black Rock Channel enters Lake Erie. When the Erie Canal was dedicated in 1825, its conceiver, New York State governor DeWitt Clinton planned to take waters from Lake Erie at Buffalo's western terminus of the canal (now the Commercial Slip), and pour it into the Atlantic Ocean in New York City. He sailed to New York on the canal packet Seneca Chief.[162] The seawater was poured into the Lake by Judge and future Buffalo Mayor Samuel Wilkeson. Once a major route for passengers and cargo, the Erie Canal played a primary role in opening up the American West to settlers from the east. The canal is now used primarily for pleasure craft and some light local freight, and in Buffalo it bypasses the swift upper reach of the Niagara River. A tributary of the Niagara River is Scajaquada Creek, which flows though Buffalo, via the Olmsted-designed Delaware Lake and Park.

Streets and highways

Eight New York State highways, one three-digit Interstate Highway and one U.S. Highway traverse the city of Buffalo. New York State Route 5, commonly referred to as Main Street within the city, enters through Lackawanna as a limited-access highway and intersects with Interstate 190, a north-south highway connecting Interstate 90 in the southeastern suburb of Cheektowaga with Niagara Falls. NY 354 (Clinton Street) and NY 130 (Broadway Avenue) are east to west highways connecting south and downtown Buffalo to the eastern suburbs of West Seneca and Depew. NY 265 (Delaware Avenue) and NY 266 (Niagara Street and Military Road) both originate in downtown Buffalo and terminate in the city of Tonawanda.

One of three U.S. highways in Erie County, the others being U.S. 20 and U.S. 219, U.S. 62 (Bailey Avenue) is a north to south trunk road that enters the city through Lackawanna and exits at the Amherst town border at a junction with NY 5. Within the city, the route passes by light industrial developments and high density areas of the city. Bailey Avenue has major intersections with Interstate 190 and the Kensington Expressway.

Three major expressways serve the city of Buffalo. The Scajaquada Expressway (NY 198) is primarily a limited access highway connecting Interstate 190 near Squaw Island to New York State Route 33. The Kensington Expressway (NY 33) begins at the edge of downtown and the city's East Side, continues through heavily populated areas of the city, intersects with Interstate 90 in Cheektowaga and ends shortly at the airport.

The Peace Bridge is a major international crossing located near the Black Rock district of the city. The bridge connects Fort Erie, Ontario with the city.

Utilities

Buffalo’s water system was begun in 1827 with the founding of the Buffalo & Black Rock Jubilee Water Works. This was followed in 1852 by the founding of the Buffalo Water Works Co. In 1868, the City of Buffalo bought both companies.[163] The remains of the first water crib built by the city are still visible in the Niagara River just downstream of the Peace Bridge. This was replaced by a new water intake in 1907. The current water intake is in Emerald Channel, approximately halfway between the Buffalo Main Light and the ruins of the pier at Erie Beach in Fort Erie. From the water intake, the water goes to the Colonel Ward Pumping Station.[164] Currently, Buffalo’s water system is operated by Veolia Water.[165]

In order to reduce large-scale ice blockage blockage in the Niagara River, with resultant flooding, ice damage to docks and other waterfront structures, and blockage of the water intakes for the hydro-electric power plants at Niagara Falls, the New York Power Authority and Ontario Power Generation have jointly operated the Lake Erie-Niagara River Ice Boom since 1964. The boom is installed on December 16, or when the water temperature reaches 4 °C (39 °F), whichever happens first. The boom is opened on April 1 unless there is more than 650 square kilometres (250 sq mi) of ice remaining in Eastern Lake Erie. When in place, the boom stretches 2,680 metres (8,790 ft) from the outer breakwall at Buffalo Harbor almost to the Canadian shore near the ruins of the pier at Erie Beach in Fort Erie. Originally, the boom was made of wooden timbers, but these have been replaced by steel pontoons.[166]

Media

Buffalo’s major newspaper is The Buffalo News. Established in 1880, the newspaper has 181,540 in daily circulation and 266,123 on Sundays. Other newspapers in the Buffalo area include Artvoice, The Beast, Buffalo Business First, the Spectrum, University at Buffalo’s student-run newspaper, and the Record, Buffalo State College’s student-run newspaper. Online news magazines include Artvoice Daily Online and Buffalo Rising, formerly a print magazine.

The Buffalo area is home to 14 AM stations and 21 FM stations. Major station operators include Entercom, Townsquare Media and Cumulus Media. In addition, National Public Radio operates a publicly funded station, WBFO 88.7.

According to Nielsen Media Research, the Buffalo television market is ranked as the 52nd largest in the United States as of 2013.[167] Although no major cable outlets have offices or bureaus in the Buffalo area, major networks have an established presence in the area, including WGRZ (NBC), WIVB-TV (CBS), WUTV (FOX), WKBW-TV (ABC). Other networks with Buffalo stations include publicly funded WNED-TV (PBS), WNLO (The CW), WNYO-TV (MyNetworkTV), and WBBZ-TV (MeTV/independent). The area's major cable provider is Time Warner Cable, which operates the system-exclusive Time Warner Cable News Buffalo, part of the statewide Time Warner Cable News network. The Buffalo market also has access to multiple Canadian broadcast stations over-the-air from the Hamilton and Toronto areas, though only CBLT (CBC) and CFTO (CTV) are carried on Time Warner Cable.

Movies shot with significant footage of Buffalo include Bruce Almighty (2003),[168] Buffalo '66 (1998),[169] Henry's Crime (2010),[170] Hide in Plain Sight (1980),[171] Proud (2004),[172] Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles 2 (2016), and The Natural (1984).[173]

Notable people

International relations

Buffalo has a number of sister cities as designated by Sister Cities International (SCI):[174][175]

-

Siena, Italy (1961)[174][176]

Siena, Italy (1961)[174][176] -

Kanazawa, Japan (1962)[174][177]

Kanazawa, Japan (1962)[174][177] -

Dortmund, Germany (1972)[174][178]

Dortmund, Germany (1972)[174][178] -

Rzeszów, Poland (1975)[174][179][180]

Rzeszów, Poland (1975)[174][179][180] -

Cape Coast, Ghana (1976)[174]

Cape Coast, Ghana (1976)[174] -

Aboadze, Ghana[174]

Aboadze, Ghana[174] -

Kiryat Gat, Israel (1977)[174]

Kiryat Gat, Israel (1977)[174] -

Tver, Russia (1989)[174][181]

Tver, Russia (1989)[174][181] -

Drohobych, Ukraine (2000)[174][182]

Drohobych, Ukraine (2000)[174][182] -

Lille, France (2000)[174][183]

Lille, France (2000)[174][183] -

Torremaggiore, Italy (2004)[174][184]

Torremaggiore, Italy (2004)[174][184] -

Abuja, Nigeria (2004)[174]

Abuja, Nigeria (2004)[174] -

Saint Ann's Bay, Jamaica (2007)[174][185]

Saint Ann's Bay, Jamaica (2007)[174][185]

While there is no formal relationship, Buffalo and Toronto enjoy a close link and friendly rivalry.

Consulates in Buffalo

Honorary Consulates:

See also

- Buffalo Airfield

- Buffalo Central Terminal

- Buffalo City Hall

- Buffalo Fire Department

- Polish Cathedral style

- South Buffalo, Buffalo, New York

- Buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo

Notes

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 First White Settlement and Black Joe – Buffalo, NY. The Buffalonian. Retrieved April 15, 2008. Archived March 22, 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ The Village of Buffalo 1801 to 1832. The Buffalonian. Retrieved April 15, 2008. Archived March 22, 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Erie County Government: Overview. Erie County (New York) Government Home Page. Retrieved April 16, 2008. Archived April 5, 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Large Metropolitan Statistical Areas—Population: 1990 to 2010" (PDF). Statistical Abstract of the United States. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- ↑ "Incorporated Places With 175,000 or More Inhabitants in 2010— Population: 1970 to 2010" (PDF). Statistical Abstract of the United States. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- ↑ United States Census Bureau. "Annual Estimates of the Population of Combined Statistical Areas: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2011" (XLS). Population Estimates. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- ↑ Table 1. Rank by Population of the 100 Largest Urban Places, Listed Alphabetically by State: 1790–1990. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved April 11, 2012. Archived September 12, 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Early Railways in Buffalo. The Buffalonian. Retrieved April 16, 2008. Archived March 22, 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Buffalo as a Flour Milling Center" by Laura O'Day. Economic Geography, Vol. 8, No. 1 (Jan. 1932), pp. 81–93. Published by: Clark University.

- ↑ Buffalo History. Buffalo History. Retrieved March 31, 2010. Archived January 18, 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved March 31, 2010. Archived July 24, 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Best Place For Business and Careers". Forbes. Archived from the original on October 20, 2013. Retrieved 2013.

- ↑ Buffalo: Economy. City-Data.com. Retrieved March 31, 2010. Archived September 12, 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Economic Summary: Western New York Region. New York State Senate. Retrieved March 31, 2010. Archived January 8, 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Buffalo Niagara Medical Campus. Urban Design Project. Retrieved March 31, 2010. Archived July 3, 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ What is UB 2020?. University at Buffalo. Retrieved March 31, 2010. Archived May 30, 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ . www.bls.gov. Retrieved June 18, 2014.

- ↑ Levy, Francesca (June 7, 2010). "America's Best Places to Raise a Family". Forbes.com. Archived from the original on April 2, 2014.

- ↑ "Buffalo Widely Knows as 'City of Good Neighbors'". Washington Afro-American. August 14, 1951. p. 20. Retrieved April 4, 2010.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Can Buffalo Ever Come Back? from City Journal Archived December 3, 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Houghton, Frederick (1927). "The Migrations of the Seneca Nation". American Anthropologist 29: 241–250. doi:10.1525/aa.1927.29.2.02a00050.

- ↑ Buffalo Historical Society; Buffalo Historical Society (Buffalo, N.Y.) (1902). Buffalo Historical Society Publications. Bigelow Brothers. p. 15. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 You asked us: The 868–3900 line to your desk at the Star: How Buffalo got its name, Toronto Star, Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Toronto Star, September 24, 1992, Stefaniuk, W., Retrieved April 23, 2014.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Worldly setting, sophisticated choices, atmosphere at Beau Fleuve, Buffalo News, Buffalo, NY: Berkshire Hathaway, March 19, 1993, Okun, J., Retrieved April 23, 2014.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 'Beau Fleuve' story doesn't wash, Buffalo News, Buffalo, NY: Berkshire Hathaway, July 21, 2003, Retrieved April 23, 2014.

- ↑ American bison#mediaviewer/File:Bison original range map.svg

- ↑ Priebe Jr., J. Henry. "Beginnings —The Village of Buffalo – 1801 to 1832". Archived from the original on September 5, 2013. Retrieved September 7, 2007.

- ↑ "The Buffalonian". The Buffalonian. Archived from the original on August 24, 2013.

- ↑ "History of Buffalo". Buffaloah.com. Archived from the original on October 18, 2012.

- ↑ Quimby, Robery (1997). The U.S. Army in the War of 1812: An Operational and Command Study. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press. p. 355. ISBN 0-87013-441-8.

- ↑ "Erie Canal opens". The History Channel website. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- ↑ "Canal History". New York State Canals. New York State Canal Corporation. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- ↑ Champieux, Robin (April 2003). "John W. Clark papers". William L. Clements Library. University of Michigan. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 "A Brief Chronology of the Development of the City of Buffalo". National Park Service. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Fordham, Monroe (April 1996). "Michigan Street Church". African American history of Western New York. Archived from the original on July 21, 2012. Retrieved September 8, 2007.

- ↑ Fordham, Monroe. "Michigan Street Church". African American History of Western New York. University at Buffalo. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- ↑ "African American history of Western New York". Archived from the original on July 20, 2012. Retrieved September 8, 2007.

- ↑ "Underground Railroad Sites in Buffalo, NY". Archived from the original on October 15, 2013. Retrieved July 25, 2010.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Priebe Jr., J. Henry. "The City of Buffalo 1840–1850". Archived from the original on September 5, 2013. Retrieved September 9, 2007.

- ↑ Baxter, Henry. "Grain Elevators" (PDF). Buffalo and Erie County Historical Society. Buffalo and Erie County Historical Society. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- ↑ "Buffalo, New York - Inaugural Journey". National Park Service. February 17, 2011. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 LaChiusa, Chuck. "The History of Buffalo: A Chronology Buffalo, New York 1841–1865". Archived from the original on May 26, 2007. Retrieved September 8, 2007.

- ↑ Beveridge, Charles. "Frederick Law Olmsted Sr.". National Association for Olmsted Parks. Retrieved November 2, 2014.

- ↑ http://www.pbs.org/wned/frederick-law-olmsted/learn-more/olmsteds-buffalo-park-system-and-its-stewards/

- ↑ "WHEN GROVER CLEVELAND ACTED AS HANGMAN". The New York Times. July 7, 1912. Retrieved November 2, 2014.

- ↑ "Grover Cleveland". Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- ↑ "Ellicott Square Building: 295 Main St.". Ellicott Development. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

- ↑ "Ellicott Square Building". Emporis.com. Retrieved 2008-02-29.

- ↑ Believe it, or not. Clymer, Floyd. Treasury of Early American Automobiles, 1877–1925 (New York: Bonanza Books, 1950), p.178.

- ↑ "The History of Buffalo". Buffaloah.com. Archived from the original on October 9, 2012.

- ↑ "President William McKinley is shot". The History Channel website. Retrieved November 2, 2014.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 "Swearing-In Ceremony for President Theodore Roosevelt". Joint Congressional Committee on Inaugural Ceremonies. Retrieved November 2, 2014.

- ↑ "Peace Bridge Facts". The Peace Bridge. Buffalo and Fort Erie Public Bridge Authority. Retrieved November 2, 2014.

- ↑ Hirtzel, Ashley (September 3, 2014). "Buffalo Central Terminal restoration plans aim to boost regional tourism". WBFO 88.7. Retrieved November 2, 2014.

- ↑ "1941–1945". History. Parkside Community Association. Archived from the original on July 8, 2010.

- ↑ Rizzo, Michael. "Joseph J. Kelly 1942–1945". Through The Mayor's Eyes. The Buffalonian. Archived from the original on September 26, 2011.

- ↑ "Buffalo Car Company". April 9, 2006. Archived from the original on March 12, 2012.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 "Back in business". The Economist (The Economist Newspaper Limited). June 30, 2012. Retrieved November 2, 2014.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 Goldman, Mark (1983). High hopes : the rise and decline of Buffalo, New York. State University of New York: State University of New York Press. pp. 270, 271, 294. ISBN 9780585093062.

- ↑ "Population of the 100 Largest Urban Places: 1950". United States Census. June 15, 1998. Retrieved November 2, 2014.

- ↑ "current city development projects 2007" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 4, 2013. Retrieved November 4, 2007.

- ↑ Spector, Joseph (May 23, 2013). "Buffalo Continues Population Slide". WGRZ. Gannett. Retrieved November 2, 2014.

- ↑ Kaplan, Melanie (July 24, 2014). "In Buffalo, N.Y., a new vitality is giving the once-gritty city wings". Washington Post. Retrieved September 19, 2014.

- ↑ Ouroussoff, Nicolai (November 14, 2008). "Saving Buffalo’s Untold Beauty". The New York Times. Retrieved September 19, 2014.

- ↑ "Buffalo, NY". Forbes. Forbes.com LLC. Retrieved September 19, 2014.

- ↑ "Calvert Vaux and Olmsted Sr.". National Association for Olmstead Parks. Retrieved September 19, 2014.

- ↑ Louis Sullivan – Guaranty / Prudential Building. Retrieved July 7, 2007 Archived July 2, 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Governor Cuomo Announces First Phase of Redevelopment of Richardson Olmsted Complex in Buffalo". Governor Andrew M. Cuomo. State of New York. January 25, 2013. Retrieved September 19, 2014.

- ↑ William Heath House. Retrieved July 7, 2007 Archived December 28, 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Graycliff Wright on the Lake". Graycliffestate.org. Archived from the original on October 9, 2013., Retrieved 2013-5-31.

- ↑ "Rowing". Frank Lloyd Wright's Fontana Boathouse. Retrieved September 19, 2014.

- ↑ Temple Beth Zion. Retrieved July 7, 2007. Archived March 13, 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Buffalo Neighborhoods".

- ↑ "American Planning Association". Retrieved October 4, 2007 Archived October 11, 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Forever Elmwood – The Elmwood Village Association". Foreverelmwood.org. Archived from the original on August 10, 2013. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- ↑ "Buffalo’s decade-long dust bowl" article by Dan Telvock in Investigative Post April 3, 2014 Archived April 7, 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Citizens Advisory Commission on Reapportionment Redistricting Plan as Amended by the City of Buffalo Common Council" (PDF). City of Buffalo. May 27, 2011. Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- ↑ Madsen, Steve. "Comparison Golden Snowball City Stats 1940 – 2007". Goldensnowball. Archived from the original on February 8, 2014., Retrieved 2013-5-31.

- ↑ WeatherBug Meteorologists (January 3, 2012). "What Are The Snowiest Cities in the U.S.?". Weatherbug., Retrieved 2013-5-31.

- ↑ "Buffalo socked by wintry October surprise". WISTV. October 13, 2006. Retrieved September 30, 2014.

- ↑ "October Surprise Storm: 7th Anniversary". WGRZ. Gannett.

- ↑ AFP (19 November 2014). "At least eight dead in 'historic' US snowstorm". Terra Daily.

- ↑ "Deadly snowstorms cause roof collapses in Buffalo area". CBS News & Associated Press. November 20, 2014. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

- ↑ Ray Sanchez and Steve Almasy (November 21, 2014). "Heavy snow plus rain could spell more trouble for Buffalo homeowners". CNN. Retrieved November 21, 2014.

- ↑ Buffalo's Climate. National Weather Service. Retrieved July 5, 2006. Archived May 14, 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Record high of 99 °F (37 °C) was recorded in August 1948". Weather.com. July 27, 2012. Archived from the original on December 7, 2013.

- ↑ "August Daily Averages for Buffalo, NY". weather.com. Archived from the original on March 16, 2014. Retrieved December 6, 2011.

- ↑ "February Daily Averages for Buffalo, NY". weather.com. Archived from the original on March 16, 2014. Retrieved December 6, 2011.

- ↑ "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2011-12-22.

- ↑ "Station Name: NY BUFFALO". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2014-03-13.

- ↑ "WMO Climate Normals for Buffalo/Greater Buffalo, NY 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved December 10, 2013.

- ↑ "Monthly Averages for Buffalo, NY". The Weather Channel. Retrieved 2010-12-19.

- ↑ "Census". United States Census. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 24, 2013. page 36

- ↑ United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Archived from the original on April 22, 2013. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2012". Archived from the original on October 19, 2013. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- ↑ "Buffalo (city), New York". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on May 4, 2014.

- ↑ 97.0 97.1 97.2 97.3 "Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 6, 2012.

- ↑ 98.0 98.1 From 15% sample

- ↑ "Buffalo Demographics: 2010". quickfacts.census.go. Archived from the original on May 4, 2014. Retrieved November 8, 2011.

- ↑ "Buffalo, New York (NY) Detailed Profile – relocation, real estate, travel, jobs, hospitals, schools, crime, news, sex offenders". City-data.com. Archived from the original on September 27, 2013.

- ↑ http://wings.buffalo.edu/sa/muslim/LocalMosques.htm Archived February 12, 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "UN: Major inequality in US cities – Americas". Al Jazeera English.

- ↑ "Segregation: Dissimilarity Indices". CensusScope.

- ↑ University at Buffalo Regional Institute (2011). "Binational Buffalo Niagara Region Report". Regional Knowledge Network. UB Regional Institute. Archived from the original on March 22, 2012. Retrieved February 2, 2011.

- ↑ Rott, Jerry (July 26, 2013). "List: Largest Employers". Buffalo Business First. American City Business Journals. Retrieved September 19, 2014.

- ↑ "See Erie County". Labor.state.ny.us.

- ↑ "BLS, Table 1. Covered establishments, employment, and wages in the 326 largest counties, fourth quarter 2006". Bls.gov. Archived from the original on April 19, 2014.

- ↑ "New York". Labor.state.ny.us.

- ↑ "''bizjournals.com''". Bizjournals.com. October 24, 2012. Archived from the original on May 8, 2014.

- ↑ Thompson, Carolyn (January 5, 2010). "Buffalo's debt collectors accused of bullying =". Associated Press. Archived from the original on January 8, 2010. Retrieved January 5, 2010.

- ↑ / Archived June 26, 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Our Locations". Del Monte Foods. Retrieved September 19, 2014.

- ↑ "Poverty USA – Catholic Campaign for Human Development – A hand up, not a hand out". Usccb.org. July 27, 2011. Archived from the original on July 10, 2011.

- ↑ Buffalo 3rd Poorest Large City. WGRZ TV. Retrieved October 14, 2008.

- ↑ Buffalo falls to second-poorest big city in U.S., with a poverty rate of nearly 30 percent. Buffalo News. Retrieved September 2, 2007. Archived October 11, 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Buffalo Market Trends". Trulia. Retrieved September 19, 2014.

- ↑ Ken Belson (September 13, 2007). "Vacant Houses, Scourge of a Beaten-Down Buffalo". The New York Times. Retrieved April 28, 2015.

- ↑ Derek Burnett, America's Top Five Cleanest Cities. Reader's Digest. Retrieved January 4, 2007. Archived September 26, 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Buffalo Economy News". City of Buffalo. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

- ↑ "Signs of economic revival finally appear". The Buffalo News. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

- ↑ New York State Department of Labor (April 21, 2015). "State Labor Department Releases Preliminary March 2015 Area Unemployment Rates". Labor.ny.gov. Retrieved April 28, 2015.

- ↑ National Conference of State Legislatures (April 3, 2015). "National Employment Monthly Update". Ncsl.org. Retrieved April 28, 2015.

- ↑ Addotta, Kip. "Pizza!". Kip Addotta dot com. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved July 3, 2009.

- ↑ "Famous Buffalo and Western New York Foods, Restaurants & Food Festivals". Buffalo Chow.com. Archived from the original on September 7, 2013. Retrieved July 3, 2009.

- ↑ "Top 100 Buffalo/WNY Foods (and Restaurants), Part 1 of 5". Buffalo Chow.com. February 10, 2009. Archived from the original on September 13, 2013. Retrieved July 3, 2009.

- ↑ Shurtleff, William; Aoyagi, Akiko (2013). History of Non-Dairy Whip Topping, Coffee Creamer, Cottage Cheese, and Icing/Frosting (With and Without Soy) (1900-2013) (PDF). p. 6. ISBN 978-1-928914-62-4.

- ↑ "Leading Businesses and Brands". Buffalo Niagara Enterprise. Retrieved September 19, 2014.

- ↑ World Grain Staff (May 13, 2013). "ADM to reopen flour mill after fire". World-Grain Report., Retrieved 2013-5-31.