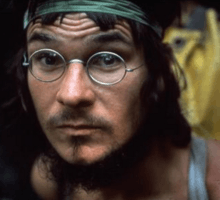

Bruno Manser

| Bruno Manser | |

|---|---|

Bruno Manser, ca. 1987 | |

| Born |

25 August 1954 Basel, Switzerland |

| Disappeared |

25 May 2000 (aged 45) Bukit Batu Lawi, Sarawak, Malaysia |

| Status | Legally dead on 10 March 2005 |

| Residence | Heuberg 25, Basel, Switzerland |

| Nationality | Swiss |

| Other names |

Laki Penan Laki Tawang Laki e'h metat |

| Occupation |

Human rights activist Environmentalist |

| Organization | Bruno Manser Fonds |

| Title | Chairman |

| Predecessor | Post created |

Bruno Manser (born 25 August 1954, declared dead 10 March 2005) was a Swiss environmental activist.

From 1984 to 1990, he stayed with the Penan tribe in Sarawak, Malaysia, organising several blockades against timber companies. After he emerged from the forests in 1990, he engaged in public activism for rainforest preservation and the human rights of indigenous peoples, especially the Penan, which brought him into conflict with the Malaysian government. He also founded the Swiss NGO "Bruno Manser Foundation" in 1991.

Manser disappeared during his last journey to Sarawak in May 2000 and is presumed dead.

Early life and education

Bruno Manser was born in Basel on 25 August 1954 in a family of 3 girls and 2 boys. During his younger days, Manser has challenged the epistemological dictates of "civilisation". Manser's parents wanted him to become a doctor. Manser also underwent an informal medical study.[1] He completed upper secondary education (baccalaureate).[2] He was also the only one in the family to finish his schools. During autumn and winter months, Manser would make a bed on the balcony out of tree branches and ferns and slept on it.[3] Manser spent 3 months in Lucerne prison when he was 19 years old because he refused Switzerland's compulsory military service. Manser was familiar with non-violent ideologies of Satyagraha by Mahatma Gandhi. After he leaves prison in 1973, he worked as a sheep and cow herder[4] at various Swiss Alpine pastures for 12 years. During this time, he became interested in handicrafts, therapeutics, and speleology. He laid bricks, carved leather, kept bees, wove, dyed, and cut his own clothes and shoes. He also regularly pursue mountaineering and technical climbing.[1] At the age of 30, he went to Borneo because of his desire to live a life without money.[2]

Searching for Penans

In 1983, Manser went to the Malaysian state of Terengganu and stayed with a family. In 1984, Manser read on a dozen of books about rainforests in a university library. He came across a tribe called "Penan" who were still living in the jungles as nomads in Sarawak. Since then, Manser decided that he should live with the Penans for a few years. Manser travelled to the East Malaysian state of Sarawak in 1984 on a tourist visa. He joined English caving expedition to explore Gunung Mulu National Park. After that, he stepped deeper into the interior jungles of Sarawak, intending to find the "deep essence of humanity" and "the people who are still living close to their nature".[1] However, he was lost and ran out of food while exploring the jungle. He also fell ill after eating a poisonous palm heart.[3] However, he survived in the jungle and he finally found Penan nomadic tribes near river source of Tutoh or Limbang river[4] at Long Seridan in May 1984.[5] Initially, the Penan people tried to ignore him. However, he continued to follow them and the Penans decided to take him as one of their family members.[3] In August that year, he went to Kota Kinabalu, Sabah to obtain a visa to visit Indonesia. With the Indonesian visa, he entered Kalimantan and made an illegal border crossing back into Long Seridan, Sarawak. His Malaysian visa expired on 31 December 1984.[4][5]

Life with the Penans

Manser learned about survival skills in the jungle, familiarise himself with the Penan's culture and language.[2] Penan tribal leader in Upper Limbang named Along Sega, became Manser's mentor.[6] Manser adopted Penan way of life absolutely. He dressed in a loincloth, hunting with a blowgun, eating primates, snakes, and sago. Manser's new way of life has been ridiculed in the West and he was dismissed as a "White Tarzan".[1] Manser was regarded by the Penan community as Laki Penan (Penan Man) - the respect of the Penan for their adopted brother.[1][7] Manser created notebooks richly illustrated with drawings, notes, and 10, 000 photographs during his 6 years stay from 1984 to 1990 with the Penan people.[2] Some of his sketches includes: cicada wings patterns, how to carry a gibbon with a stick, and how drill holes on a blowpipe.[3] These notebooks were later published by Christoph Merian Verlag press in Basel.[2] Manser also created audio recordings of oral histories told by Penan elders and translated them. Manser claimed that he never witnessed any arguments or violence among the Penan people during his six-year stay with the Penans.[1] In 1988, Bruno Manser tried to reach the summit of Bukit Batu Lawi but it was unsuccessful and he was hanging on a rope without anything to grab on for 24 hours.[3] In 1989, Manser was bitten by a red tailed pit viper but he was able to treat the snake bite himself.[1] He also got a malaria infection while living in the jungles.[3]

However, deforestation of Sarawak's primeval forests also began at that time. This has caused problems for the Penans such as reduced vegetation, contaminated drinking water, fewer animals available for hunting, and desecration of Penan's heritage sites. Manser together with his mentor, Along Sega, began to teach Penans organising road blockades against advancing loggers. Manser organised his first blockade in September 1985 and helped to draw up declaration of Long Seridan.[4][8]

Activism

Manser gave many lectures in Switzerland and abroad, made contacts with European Union (EU) and United Nations (UN).[7] Catholic and Protestant leaders of Switzerland churches often dedicated their services to Bruno Manser.[1] He also visited American and African jungles and stayed there for a few weeks. He went back to Sarawak almost every year undercover to follow up with the logging activities and to provide assistance to Penans. He usually did this by carrying out illegal border crossings from Brunei and Kalimantan, Indonesia.[3] However, logging companies such as Samling, Rimbunan Hijau, and WTK continue their operations in Sarawak rainforests.[7]

Manser organised "Voices for the Borneo Rainforests" World Tour after he emerged from the Sarawak forests in 1990. Manser, together with Kelabit activist Anderson Mutang Urud, and two Penans travelled from Australia to North America, Europe, and Japan.[9]

On 17 July 1991, Manser climbed unaided to the top of 30-foot high lamp post outside G7 media centre in London. He then unrolled a banner which contained a message about the plight of Sarawak rainforests and chained himself to the lamp post for two and a half hours. His protest also coincided with protests by Earth First! and London Rainforest Action Group. Police used a hoist to reach the top of the lamp post and chains were cut. Manser came down from the lamp post without force at 1.40 pm. He was later taken to Bow street police station and held until G7 summit ends at 6.30 pm. He was released without any charge.[10][11]

In June 1992 he parachuted into a crowded stadium during the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.[9]

In December 1992, Manser led a 20-day hunger strike in front of Marubeni Corporation headquarters in Tokyo, Japan.[1]

In 1993, Manser went on a 60-day hunger strike at Federal Palace of Switzerland (Bundeshaus) to press the Swiss parliament on enforcing a ban on tropical timber imports and mandatory declarations of timber products. The strike was supported by 37 organisations and political parties.[2][7][12] Manser only decided to stop the hunger strike on request of his mother.[3] The Swiss parliament only adopted the Declaration of Timber Products on 1 October 2010, with transition period until the end of year 2011.[13]

In 1995, Manser went to Congo rainforests to document the effects of wars and logging on Ituri pygmies.[1]

In 1996, in the programme "fünf vor zwölf" (At the eleventh hour), Manser and Jacques Christinet dropped themselves down 800 meters along auxiliary cable down the Klein Matterhorn aerial cable car and hung huge banners there.[1][7] They reached a dangerous speed of 140 km/hour while riding on a self-made rider with steel wheels and ball bearings.[3]

In 1997, Manser and his friend tried to enter Peninsular Malaysia from Singapore to fly a motorised hang-glider during the 1998 Commonwealth Games in Kuala Lumpur. However, he was recognised at the border and was denied entry into Malaysia. He and his friend then decided to swim across the Straits of Johor into Malaysia but later abandoned the plan because of a long 25 km swim and a passage through a swamp across the straits. They also planned to row a boat from an island in Indonesia into Sarawak but Bruno Manser Fonds in Switzerland received a warning from Malaysian embassy on not to try such an act.[3]

In 1998, they travelled to Brunei and swam across a 300 metres wide Limbang river at night. Manser's friend was almost fatally injured by floating logs on the river. They spent 3 weeks in Sarawak while hiding from the police. They attempted to order 4 tons of 25-cm nails for the Penans to hammer into the tree trunks. Such nails could cause serious injuries to the loggers when the embedded nails come into contact with chainsaws.[3]

As a result of Manser's actions, Al Gore condemned logging activities in Sarawak. Prince Charles also described the treatment for Penans as "genocide".[3] BBC and National Geographic Channel started to produce documentaries about Penans. Penan stories were also featured on Primetime Live. Universal Studios started to develop action-adventure horror script where Penans used their forest wisdom to save the world from catastrophe. Warner Bros also developed a script on Bruno Manser story. The Penans also received coverage in Newsweek, Time, and The New Yorker.[9]

Response from Malaysian authorities

Manser actions drew angers from Malaysian authorities and was nearly arrested in 1986. Manser also became persona non grata (an unwelcome person) in Malaysia. Bounty ranged from US$ 30, 000[14] to US$ 50,000[15] has been circulated by word-of-mouth for his head but the source of the bounty is unknown.[1] By 1990, Malaysia has declared Bruno Manser as "No.1 enemy of the state" and sent special units to look for him.[7] By using a forged passport and a new haircut,[3] Manser was able to return to Switzerland in 1990 and to inform the public about the situation in Sarawak through Swiss media.[2] Natives blockades in Sarawak had already started since the 1970s, and the police force was involved in 20 to 30 preventive actions per year between 1982-1984. Therefore, Manser explicitly denied that he is the author of blockading among the Penans.[4]

Bruno Manser was nearly captured twice in Sarawak but he successfully escaped from it. The first arrest was on 10 April 1986. Police inspector named Lores Matios was on a holiday at Long Napir, Limbang when he came across Bruno Manser. He decided to arrest Manser and bring him to Limbang police station. Manser was not on handcuff because the inspector did not bring any handcuff with him during his holiday. During the 90-minute ride to Limbang, the Land Rover which Bruno Manser is riding was running out of petrol. Manser decided to jump out of the Land Rover and dive into a river during petrol filling of the vehicle. The inspector shouted at him and fired 2 shots of pistol at Manser. Manser also lost all his notebooks which he has done for the past four years.[3][16] Bruno Manser was nearly arrested for the second time on 25 March 1990 when he met the same police inspector during a flight from Miri to Kuching. The police inspector was on his way to take a law exam in Kuching. However, the inspector did not arrest Manser.[16]

Response by Malaysian federal government

Prime minister of Malaysia, Mahathir Mohamad blamed Manser for disrupting law and order. Mahathir also wrote a letter to Manser, telling him that it was "about time that you stop your arrogance and your intolerable European superiority. You are no better than the Penan."[3] In 1987, Mahathir used Internal Security Act (ISA) to jail critics of the regime and to neutralise Penan campaigners. Over 1,200 people has been arrested for challenging logging and 1,500 Malaysian soldiers and police dismantled barricades, beaten, and arrests people. During a meeting of European and Asian leaders in 1990, Mahathir said,"It is our policy to bring all jungle dwellers together into the mainstream. There is nothing romantic about these helpless, half-starved, and disease-ridden people."[17]

Malaysian authorities also argued that it is unfair to accuse Malaysia of destructing their own rainforests while the western civilisation continued to cut their own forests down. Preservation of rainforests would mean closing down factories and hinder industrialisation which would result in unemployment issues. Instead of focusing on human rights of Penans, the western activists should focus instead on minorities in their own countries such as Red Indians in North America, Aboriginal Australians, Māori people in New Zealand and Turks in Germany.[9] Malaysian Timber Industry Development Board (MTIB) and Sarawak Timber Industry Development Cooperation (STIDC) spent RM 5 to 10 million in producing a research report to counter allegations by foreign activists.[18]

Response by Sarawak state government

The Sarawak government defended its logging policy by stating that revenue from timber sales is needed to feed more than 250,000 of the state population. Sarawak chief minister Abdul Taib Mahmud said, "It is hoped that outsiders will not interfere in our internal affairs, especially people like Bruno Manser. The Sarawak government has nothing to hide. Ours is an open liberal society."[18] Sarawak Minister of Housing and Public Health, James Wong said that "We don't want them (the Penans) running around (in jungles) like animals. No one has the ethical right to deprive the Penans of the right to assimilation into Malaysian society."[17] The Sarawak government tightened the entry of foreign environmentalists, journalists, and film crews into the state.[18] Sarawak government also allowed logging companies to hire criminal gangs to subdue the indigenous people.[1]

Press censorship

The Economist was banned twice in 1991 for articles that commented critically on Malaysian government. Its distribution was deliberately delayed three times. Newspaper editors would receive a phone call from Ministry of Information, warning them to "go easy" on particular topic. Few negative reports such as logging, appeared on domestic newspapers because of high degree of self-censorship. "Mingguan Waktu" newspaper was banned in December 1991 because of publishing criticisms of Mahathir administration. Mahathir defended the press censorship. He told ASEAN that foreign journalists "fabricate stories to entertain and make money out of it, without caring about the results of their lies".[19]

Dealing with Abdul Taib Mahmud

In mid-1998, Manser offered an end of hostilities with Sarawak government if Sarawak chief minister Abdul Taib Mahmud is willing to co-operate with him to create a biosphere around Penan people's territory. Besides, he also wanted the government to forgive him for breaking Malaysian immigration laws. The offer was denied. His successive attempts to establish communications with chief minister has failed.[7]

Manser also planned to deliver a lamb named "Gumperli" to Taib Mahmud by air as a symbol of reconciliation with the chief minister during Hari Raya Aidilfitri celebration. However, Malaysian consulate at Geneva, Switzerland pressured airlines not to transport the lamb to Sarawak. Manser later carried the lamb with him on a plane and parachuted over United Nations Office at Geneva in desperation of drawing international attention to Sarawak rainforests problem.[7]

In March 1999, Manser successfully passed Kuching immigration office by disguising himself in a business suit, carrying a briefcase, and wearing a badly knotted tie. On 29 March 1999, he flew a motorised paraglider, carrying a toy lamb knitted by himself[3] while wearing a T-shirt with the image of a sheep and made a few turns above Taib's residence in Kuching, Sarawak. There were 10 Penans waiting on the ground to greet Manser. At 11.30 am, he landed the glider beside a road, just outside of Taib's residence, and was immediately arrested. He was later transported to Kuala Lumpur using Malaysia Airlines flight MH 2683 at about 5.40 pm. He stayed briefly inside a prison in Kuala Lumpur. He was seen playing with his knitted toy lamb by his jailers.[3] He was later deported back to Switzerland.[2][5][7][12]

By the year 2000, Manser admitted that his efforts has not brought any positive changes to Sarawak. His success rate in Sarawak was "less than zero" and he was deeply saddened by the result.[1] On 15 February 2000, just before his last trip to Sarawak, Manser said that,"Through his (Taib) logging license policies, Taib Mahmud is personally responsible for the destruction of nearly all Sarawak rainforests in one generation."[7]

Bruno Manser Fonds

Bruno Manser Fonds (BMF) was set up by Bruno Manser himself in 1991, based in his home at Heuberg 25, Basel, Switzerland until 2008. BMF was moved to Socinstrasse 37 in October 2008. Daily operations of BMF is handled by a board with 7 members, an executive director, a team of employees and volunteers. BMF claimed to have a strength of 4000 members.[20] By 2000, BMF raised US$10,000 to set up mobile dental clinic for the Penan but the Sarawak government refused to co-operate on the project.[1] In September 2012, BMF released a report which valued Taib Mahmud's assets at US$ 15 billion.[21]

Disappearance

15 February 2000 was Manser's last trip to visit his Penan nomadic friends via jungle paths of Kalimantan, Indonesia. BMF secretary John Kuenzli and film crew followed him into the jungles of Kalimantan. The film crew and John Kuenzli subsequently left Manser in Kalimantan jungles. At that time, Manser was still writing postcards to his friends. He had written about 400 postcards. Manser continued the journey with another friend. The trip continued for 2 weeks where they have to cross mountains and rivers by foot and by boats. Manser slept on a hammock while his friend slept on the ground. It was rainy every day. On 18th May, they reached the Sarawak - Kalimantan border and they passed their last night there. Manser asked his friend to carry a postcard back to his life-partner in Switzerland. Manser looked healthy when his last Swedish friend left him. Manser complained about diarrhoea and broken rib in the postcard.[7]

According to BMF secretary John Kuenzli, Manser crossed the Sarawak - Kalimantan border on 22 May with the help of a local guide. His last known communication was a letter mailed to his girlfriend, Charlotte, while hiding in Bario town. In the letter, Manser said he was very tired while his was waiting for the night to arrive before continuing his journey along the logging roads. The letter was deposited at the Bario post office and reached Switzerland with a Malaysian stamp but without a post office stamp.[7] Manser was last seen carrying a 30 kg backpack by his Penan friend named Paleu and his son on 25 May 2000. They accompanied Manser until Bukit Batu Lawi (2000-metre limestone pinnacle in Sarawak) was in sight. Manser stated his intention to climb the mountain alone and requested Paleu to leave him there. Manser disappeared since then.[3]

Search expeditions

BMF and the Penans tried to search for Manser without any success. Areas around Limbang river has been cleared by Penans to find Manser. Penan expedition teams tracked Manser to his last sleeping place. They followed Manser's machete cuts into the thick forests until the trail reached the swamp at the foot of Bukit Batu Lawi. There was no trace of him in the swamp, going back from the swamp, or trace of anyone else coming into the area. BMF sent a helicopter to circle the limestone pinnacles. However, none of the search teams were willing to scale the last 100 metres of steep limestone that formed the peak of Batu Lawi.[3] Manser could have fallen down from the mountain but neither his body nor his belongings have been found.[1][22] However, two local guides who brought Manser across Sarawak jungles were found. In desperation, fortune tellers and Penan necromancer were called. All of them agreed Bruno Manser was still alive.[7] On 18 November 2000, BMF requested Federal Department of Foreign Affairs (FDFA) to search for Bruno Manser. Investigations were carried out in Swiss Consulate in Kuala Lumpur and Swiss Honoarary Consulate in Kuching.[7]

Possible explanations

- Bruno Manser could be hiding himself amongst Penans to keep the blockades going. Bruno Manser could also ask the 9000 Penans (300 still live as nomads in 2000) to keep him hidden. In July 2000, Limbang nomads had written a demand letter to the chief minister. There was also blockade on 11 August 2000 in Long Kevok. Long Kevok was a model village built by the government in the 1990s for the Penans to prevent any future blockades by them.[23][24] There was also a surge of blockades at Long Nen and Long Tunyim.[15] However, Manser has not been communicating with his family members for a long time. Before this, he will communicate with his family members no matter what circumstances arises. Roger Graf, who is an expert in Penans, said that Penans would not be secretive enough of hiding a person for so many years.[7]

- Bruno Manser was injured or ill and was under treatment in a nomadic family. Rockfalls, malaria infections, snake bites are a common occurrence in the jungles of Sarawak. Even Penans rarely go out to the jungles alone. However, Manser is an experienced jungle trekker and survival expert.[15] Penans were also not able to find him after he disappeared.[7]

- Bruno Manser is in prison. Bruno Manser was moving along the logging roads which were under constant military and police surveillance. This could be kept in secret by Sarawak government to prevent international attention.[7]

- Bruno Manser is dead. Manser could have penetrated Long Adang, a jungle region surrounded by logging companies.[25] Dangers in the jungles could have killed him or he could be killed by army, police, or loggers stationed in the area.[7] Local contacts also claimed that Malaysian military had heard of Manser's border crossing and has dispatched a search team to track him down. Since 1980s, several Penan resistance leaders have mysteriously disappeared. Logging companies also frequently hires violent gangsters as "security" forces.[15] However, Malaysian authorities had since denied that they are holding any information about the location of Bruno Manser.[22]

Aftermath

In January 2002, hundreds of Penans organised a tawai ceremony in commemoration of Bruno Manser. The Penans will address Bruno Manser as Laki Tawang (man who has become lost) or Laki e'h metat (man who has disappeared) because of taboo against speaking the names of the dead.[1] After search expeditions proved fruitless, a civil court in Basel-Stadt ruled on 10 March 2005 that Manser be considered dead.[2][12] On 8 May 2010, a memorial service was held in Elisabethen church, Basel in commemoration of Manser's 10th anniversary of disappearance in the jungles of Sarawak. About 500 people attended the church service.[26] In commemoration of Bruno Manser's 60th birthday on 25 August 2014, a species of goblin spider which was discovered by Dutch-Swiss research expedition in Pulong Tau National Park, Sarawak in the 1990s is now named after Bruno Manser as Aposphragisma brunomanseri. A new species of Murud black slender toad, Ansonia vidua, which was discovered during a night excursion near a river at an altitude of 2150 metres at Mount Murud, was also announced on the same occasion.[27]

Books

- Voices from the Rainforests (1992) written by Bruno Manser, to introduce western readers to the life of a Penan.

Films

Manser has made a film documentary:

- SAGO - A Film by Bruno Manser (1997), a documentation of the culture of the Penan.

Several documentary films have been made about him. They are:

- Blowpipes and Bulldozers (1988)

- Tong Tana - En resa till Borneos inre (1989) (In the Forest - A Journey to the heart of Borneo)

- Tong Tana 2 - The Lost Paradise (2001)

- Bruno Manser - Laki Penan (2007)

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 Taylor, B (2008). In Encyclopedia of Religion and Nature Volume I:A-J. A & C Black. p.1046-1047. ISBN 1441122788. Google Book Search. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 "Bruno Manser’s biography". Bruno Manser Fonds-for the people of the rainforest. Bruno Manser Fonds. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.9 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 3.18 Elegant, Simon (3 September 2001). "Without a Trace". Time magazine Asia. Retrieved 14 August 2014.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Eva, Maria (1 January 2004). "Protagonist of paradise: the life, death, and legacy of Bruno Manser.(Stimmen aus dem Regenwald. Zeugnisse eines bedrohten Volkes (Voices from the Rainforest. Testimonies of a Threatened People))(Tagebucher aus dem Regenwald (Diaries from the Rainforest). )(Book Review) - Subscription required". Borneo Research Bulletin. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Tawie, Sulok (30 March 1999). "Activist Bruno Manser 'flies' into arms of the law". New Straits Times. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ↑ "‘Father’ of Penan struggle, Along Sega, passes away". Free Malaysia Today. 4 April 2011. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 7.9 7.10 7.11 7.12 7.13 7.14 7.15 7.16 7.17 Suter, Reudi (2000). "Sarawak campaign - The Swiss Diplomatic Corps have started an official search for the rainforest protector". World Rainforest Movement. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ↑ Kershaw R (2011). "Against odds: A thirty-year struggle to save the forests of Sarawak". Asian Affairs (Taylor & Francis) 42 (3): 430–446. doi:10.1080/03068374.2011.605605. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Tsing, A.L(2003). In Nature In The Global South - Volume 7 of New perspectives in South Asian history. Orient Blackswan. p.332, 334. ISBN 978-1-55365-267-0. Google Book Search. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ↑ "World famous rainforest campaigner arrested after G7 lampost climb". University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. 18 July 1991. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ↑ "Earth First! Action Update (UK)" (PDF). Earth First!. Autumn 1991. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Hance, Jeremy (17 April 2008). "Photos by late Borneo rainforest hero, indigenous rights activist go online". Mongabay. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ↑ EU FLEGT Facility (2010). Changing International Markets for Timber and Wood Products (PDF) (Report). European Forest Institute. p. 8. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ↑ Human Rights Watch, Natural Resources Defense Council (1992). In Defending the Earth: Abuses of Human Rights and the Environment. Human Rights Watch. p.62. ISBN 1-56432-073-1. Google Book Search. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 "Where Is Bruno Manser? - Subscription required". Earth Island Institute through Earth Island Journal. 22 June 2001. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Ritchie, James (1994). Bruno Manser: The Inside Story. Summer Times.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Davis, W.(2007). In Light at the Edge of the World: A Journey Through the Realm of Vanishing Cultures. Douglas & McIntyre. p.140, 141. ISBN 81-250-2652-5. Google Book Search. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Mitetelman, J.H. Othman, N. (2003). In Capturing globalisation. Routledge. p.89. ISBN 0-415-25732-8. Google Book Search. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ↑ Human Rights Watch (1992). In Indivisible Human Rights: The Relationship of Political and Civil Rights to Survival, Subsistence and Poverty. Human Rights Watch. p.57. ISBN 1-56432-084-7. Google Book Search. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ↑ "Bruno Manser Fonds - The Association". Bruno Manser Fonds-for the people of the rainforest. Bruno Manser Fonds. Archived from the original on 12 August 2014. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ↑ "Taib familys illicit assets estimated at over 20 billion US dollars". Bruno Manser Fonds. September 2012. Retrieved 27 August 2014.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 David, Adrian (2 September 2001). "Mystery still surrounds missing Bruno Manser - Subscription required". New Straits Times. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ↑ "No Havoc at Long Kevok". The Borneo Project. 2000. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ↑ Thompson, Harlan (Autumn 2000). "Penan Blockade Timber Roads". The Borneo Project. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ↑ Mehta, Manik (2 February 2001). "Missing Bruno Manser in Sarawak or Kalimantan". Bernama. Retrieved 14 August 2014.

- ↑ "Missing, presumed dead - but not forgotten, Bruno Manser (1954-2000)". Bruno Manser Fonds special edition of Tong Tana. July 2010. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ↑ "Scientists honor missing activist by naming a spider after him". Mongabay. 25 August 2014. Retrieved 27 August 2014.

|