Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen and Enginemen

The Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen and Enginemen (B of LF&E) was a North American railroad fraternal benefit society and trade union in the 19th and 20th Centuries. The organization began in 1873 as the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen (B of LF), a mutual benefit society for workers employed as firemen for steam locomotives, before expanding its name in 1907 in acknowledgement that many of its members had been promoted to the job of railroad engineer.

Gradually taking on the functions of a trade union over time, in 1969 the B of LF&E merged with three other railway labor organizations to form the United Transportation Union.

Organizational history

Background

Early railway transportation relied upon steam engines to power railway locomotives — large coal-fired boilers which generated motive power through the manipulation of concentrated steam. These boilers required a regular input of fuel to keep the train fired up and running. It was the task of so-called locomotive firemen to shovel coal into a train engine's firebox through a narrow opening, thereby feeding the fire.[1]

The job of a locomotive fireman was physically demanding — strenuous, filthy, and dangerous.[1] Although by no means a highly skilled task, locomotive firemen nevertheless needed to develop not only physical prowess, moving heavy coal on a swaying platform, but also a certain job savvy, estimating the engine's burn rate and future fuel needs, making sure that water was continuously in the boiler to avoid an explosion, and ensuring that coal was sufficiently and properly spread in the firebox to ensure the locomotive's efficient operation.[1]

A locomotive's fireman worked in a tandem with the train's engineer, serving in a subordinate role as his assistant.[1] Firemen were in practice often engineers-in-training, learning the skills of train operation and assisting the engineer with the observation of signals and other routine aspects of his job performance, waiting for a job opportunity for promotion.[1]

Locomotive firemen were, consequently, lower paid and of lower status than the highly paid railroad engineers — although both of these were actually subordinate to the train's conductor.[1] It was the conductor, not the locomotive engineer, who was most comparable to the captain of a ship.[1] The conductor oversaw the crew and assigned them their mission, made sure the train ran on schedule, inspected car couplings, arranged for the train to maintain adequate supplies, collected passenger fares, and supervised the train's freight documentation.[1] Conductors acted as both supervisors and traveling clerks and were in practice the figures of the highest authority on a train.[2] Locomotive fireman generally received but half the salary of a conductor or engineer and shared in none of their authority.[2]

Despite the hard nature of the work process, their low professional status, and their mediocre pay, locomotive firemen performed very dangerous jobs. Boiler explosions and other railway accidents made railroad work among the most deadly in America at the end of the 19th Century, with an annual fatality rate in the early 1890s of approximately 9 per 1,000 workers — higher even than the 7.8 per 1,000 fatality rate suffered by hard rock miners in the Western United States.[3] Non-fatal workplace accidents were also endemic among railroad workers, with one study by the Illinois Bureau of Labor Statistics determining that railroad workers suffered more than half the broken arms and ribs, and 71 percent of all arms and legs amputated as the result of mishaps on the job.[3]

During the 19th Century occupational safety regulation was non-existent in the United States, as were the social benefits of the welfare state for employees injured on the job or the families of workers who suffered fatal accidents.[4] As a result, workers themselves endeavored to form fraternal organizations among their peers for the purposes of insurance and the payment of benefits for death or disability suffered on the job. Some of these organizations were based upon religion or ethnicity, while others were occupational in nature.[4] The Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen — later known as the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen and Enginemen — was one such organization.

Establishment

It was the engineers who pioneered occupational fraternal benefit organization in the railroad industry, with the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers launching a charity called the "Widows', Orphans', and Disabled Members' Fund" in 1866.[5] That organization went on to expand its benefits package through the establishment of a formal life insurance package via the "Locomotive Engineers' Mutual Life Insurance Association" in 1867.[5] Conductors followed by establishing their own fraternal order in 1868.[5]

Five years later came the locomotive firemen's turn to establish a fraternal benefits society of their own. This organization, the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen (B of LF) was founded on December 1, 1873 in Port Jervis, New York by Joshua A. Leach and 10 other Erie Railroad firemen.[6] These men had recently been forced to pass on the news of the fatal accident in a wreck of fellow fireman George Page to his grieving widow the previous month and decided to establish a mutual benefit society for those employed in the locomotive firemens' trade.[7] Other lodges soon followed; within a year there were a dozen functioning local groups scattered about the states of New York, New Jersey, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Indiana.[7] These met in convention in 1874 and adopted a first constitution for the organization and established a subsidiary institution called the "Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen's Life Insurance Association of the United States.[7]

Indeed, the main practical purpose of the organization was its utility as a mutual insurance association, with each member to receive death benefit coverage of 50 cents per member up to a maximum of $1,000 for loss of life on the job.[8] A second optional fund provided for disability benefits.[8] In 1881 the death benefit was pegged at a fixed level of $1,000 in 1883, with no more than 3 settlements per month to be paid, with premiums set at 50 cents per month per member.[8] Total disability through loss of an arm, leg, or eyesight on the job was to be treated the same as loss of life under the revised system.[8]

In 1884 benefits were expanded, with the death benefit raised to $1,500.[8] By February 1889 a total of $1.35 million had been paid out in benefits by the B of LF.[8] A total of 18,000 locomotive firemen were members of the organization at that date.[8]

As a general rule in the B of LF and the other similar railroad brotherhoods death and permanent disability benefits were administered by the national organization, while local lodges handled sickness and accident insurance through a separate fund, raised and disbursed independently of the national organization.[9] During the decade of the 1880s, such a local assessment might amount to 50 cents per member per month.[9] Local units also saw to the emotional support of ill or injured members, with committees visiting the bedridden and attempting to provide personal solace to family members.[10]

Organizational form

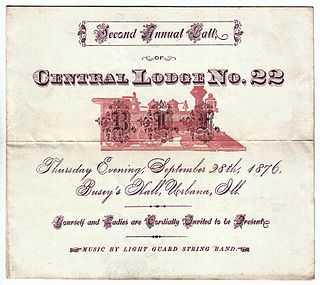

The B of LF in this early period organized itself into a network of "lodges," which provided a place for members to meet others in the profession to discuss matters of common concern. Social functions such as balls and picnics were periodically conducted under the B of LF's auspices. The organization also published a monthly magazine, The Firemen's Magazine (later Locomotive Firemen's Magazine), including railroad news of the day and articles appealing to the membership's professional interests. Little attention was paid to labor-management relations, with the B of LF mildly offering the suggestion that "the oldest firemen in service" should be promoted to positions as engineers "when they are competent and worthy, and opportunity offers."[8]

The early B of LF took the form of a secret society, complete with an elaborate initiation ritual, membership oaths, secret signs of recognition, and formulaic protocol for the conduct of lodge meetings.[11] Much of the original inspiration in this regard derived from the quasi-mystic religious tradition of Freemasonry.[11] Meetings formally opened with a prayer conducted by the lodge chaplain and were modest and subdued, emphasizing the sacred task of the organization and the need for members to maintain appropriate decorum and professionalism in daily life.[12]

In the B of LF's initiation ceremony of the 1870s, the initiate was seated in the darkened lodge room in front of a large backdrop used as a screen, while wearing a "hoodwink" — blindfolding headgear with retractable opaque lenses.[13] First the prospective member was instructed by the lodge chaplain as to the benevolent purposes of the organization and the sacred duties of the members thereof.[13] Next lodge members then joined in by collectively reciting the four principles ensconced in the organization's motto: "Protection, Charity, Sobriety, Industry."[14]

At this point a stereopticon began to project a series of images on the screen, after each of which the lenses of the hoodwink were briefly raised and the image was explained to the initiate.[14] First, a locomotive fireman leaving his family to go to work; then, a train with its crew industriously fulfilling their assigned task.[14] Next came an image of a train wreck, followed by another of a funeral attended by members of the brotherhood, paying their respects to the deceased.[14] This was followed by an image of a lodge representative relieving the grieving widow with a payment of the organization's death indemnity.[14] Having witnessed his own symbolic death, the new candidate was thus made acutely aware both of the importance of his own support of families of maimed or fallen brothers in their time of need as well as the confidence that his own family would be provided for should he himself fall to misfortune.[14]

The initiation experience was memorable and effective in building lasting commitments to the organization. Three decades after his own initiation into the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen, Eugene V. Debs recalled the evening as a watershed in his life:

"A new purpose entered my life, a fresh force impelled me as I repeated the obligation to serve the 'brotherhood,' and I left that meeting with a totally different and far loftier ambition than I had ever known before."[15]

Formulaic rituals and organizational secrecy also helped to insure that lodge meetings were orderly, intimate, and confidential and contributed to group cohesion among B of LF members.[14] The value of the B of LF's mission was emphasized, allowing serious-minded members a sense of personal fulfillment through participation in an important collective entity.[14]

Membership exclusion

The benefits of membership in the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen were not universally available, as the organization was based on the systematic exclusion of African-American men and women of all races.[16] The organization's constitution in 1888 specified that membership requirements included that a candidate be a man "white born, of good moral character, sober and industrious, sound of body and limb."[16] Additional de facto membership discrimination was practiced against recent unskilled immigrants from Europe, who were similarly held to be unsuitable for membership.[17]

The white-only rule came up for debate in 1896-97, when the B of LF explored membership in the American Federation of Labor, only to learn that the AF of L would require the removal of the offending clause from the group's constitution.[17] Rank and file membership erupted in protest over the change, flooding the organization with letters of protest, with members of lodges in the Southern United States most vociferous in their opposition.[17] The racial exclusion was ruled unconstitutional in 1944 by the Supreme Court decision "Tunstall v. Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen and Enginemen."[18]

The B of LF and other similar railroad brother hoods were, in short, based as much upon a process of exclusion as they were upon unification, as historian Mary Ann Clawson has noted in a 1989 book.[19]

Leading officials

The pioneer head of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen during the decade of the 1870s was F.W. Arnold. Arnold would be succeeded as Grand Master of the B of LF in 1885 by a man who would remain the iconic chief of the brotherhood for the rest of the 19th Century, Frank P. Sargent.[20] The New England-born Sargent remained the head official of the B of LF until 1902, when he was named Commissioner General of Immigration by Republican President Theodore Roosevelt.[20]

The eventuality of a Grand Master's incapacity to serve was provided for by the periodic election of a Vice Grand Master, nominally the second ranking officer of the organization. In practice, however, the number two functionary in the "Grand Lodge" of officers of the B of LF was the Grand Secretary and Treasurer — running the organization's office on a day-to-day basis and providing for the publication of the B of LF's monthly magazine.

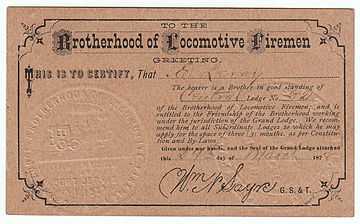

The first Grand Secretary and Treasurer was William Sayre of Galion, Ohio, professed to be a staunch advocate of the theory that personal virtue and good character, economic efficiency, and a stable and democratic republic were closely interrelated.[21] While Sayre espoused these sacred values on a theoretical plain, in practice his behavior seems to have been rather more profane. In July 1880 a young locomotive fireman turned city clerk from Terre Haute, Indiana named Eugene V. Debs was elected as Grand Secretary and Treasurer of the B of LF. Upon gaining access to the books, Debs discovered that his predecessor had been embezzling funds from the organization.[22] With the B of LF about $6,000 in debt, Debs stabilized the organization's shaky finances with a promissory note which he personally backed and began a new era of careful financial management.[22] Two years later the Brotherhood had recovered, with nearly $13,000 in the bank to the credit of the organization's 6,000 members.[22]

Debs was named editor of the Locomotive Firemen's Magazine in 1881 and he remained in that capacity and in the position of Grand Secretary and Treasurer until September 1894. While remaining supportive of the B of LF and its limited mission, over time Debs began to feel the insufficiency of a mere fraternal benefits to solve the fundamental problems facing locomotive firemen and other railway workers, which were often financial in nature and seemed to call for collective action.

In 1893 Debs was instrumental in forming an industrial union bringing together railway workers of all occupational tasks, the American Railway Union (ARU). This organization conducted several strikes for higher wages and better working conditions before ultimately being broken by judicial injunction in the 1894 Pullman strike.

Change of name

The 23rd Convention of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen, held in Milwaukee in September 1906, took the step of expanding the scope of the organization and changing its name — an idea that had been discussed for many years previously.[23] Over time a steady stream of the organization's members had been promoted to the position of Engineer, while remaining inside the organization.[23] This presented a situation in which the organization's name did not reflect its actual membership composition. Despite great sympathy for the traditional organizational moniker, the convention voted to formally acknowledge the participation of engineers among its membership and changed its name to the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen and Enginemen (B of LF&E).[23]

This change went into effect on January 1, 1907.[23]

Disestablishment and legacy

In 1969, the union merged with the Order of Railway Conductors and Brakemen, the Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen, and the Switchmen's Union of North America to form the United Transportation Union.[24]

A massive collection of materials of the B of LF&E, including over 200 linear feet of minutes, bulletins, correspondence, internal documents, and other ephemera is housed at the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives at the library of Cornell University in Ithaca, New York.[24]

Conventions and membership size

- Sources: D.B. Robertson, "Celebration of the 50th Anniversary of the B of LF&E," pp. 7-28; American Labor Year Book, 1926, pp. 106-107; ALYB, 1929, pg. 131; ALYB, 1932, pp. 63-65. The title of "Grand Master" was changed to "International President" at the convention of 1908.

| Convention | Date Called | Location | Lodges | Members | Grand Master Elected |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Convention | Dec. 15, 1874 | Hornell, NY | 12 | n/a | Joshua A. Leach |

| 2nd Annual | Dec. 14, 1875 | Indianapolis | 31 | 900 | Joshua A. Leach |

| 3rd Annual | Sept. 1876 | St. Louis | 53 | n/a | William R. Worth |

| 4th Annual | Sept. 11, 1877 | Indianapolis | 60 | n/a | Frank B. Alley |

| 5th Annual | Sept. 1878 | Buffalo | 51 | n/a (fewer) | William T. Goundie |

| 6th Annual | Sept. 8, 1879 | Chicago | 65 | n/a | Frank W. Arnold |

| 7th Annual | Sept. 1880 | Chicago | n/a | n/a | Frank W. Arnold |

| 8th Annual | Sept. 1881 | Boston | 95 | 2,998 | Frank W. Arnold |

| 9th Annual | Sept. 1882 | Terre Haute | 121 | 4,443 | Frank W. Arnold |

| 10th Annual | Sept. 1883 | Denver | 178 | 7,337 | Frank W. Arnold |

| 11th Annual | Sept. 28, 1884 | Toronto | 237 | 12,246 | Frank W. Arnold |

| 12th Annual | Sept. 22, 1885 | Philadelphia | 285 | 14,694 | Frank P. Sargent |

| 13th Annual | Sept. 15, 1886 | Minneapolis | 331 | 16,196 | Frank P. Sargent |

| 14th Convention | Sept. 10, 1888 | Atlanta | 383 | 18,278 | Frank P. Sargent |

| 15th Convention | Sept. 8, 1890 | San Francisco | 430 | 18,657 | Frank P. Sargent |

| 16th Convention | Sept. 12, 1892 | Cincinnati | 480 | 25,967 | Frank P. Sargent |

| 17th Convention | Sept. 10, 1894 | Harrisburg, PA | 519 | 26,508 | Frank P. Sargent |

| 18th Convention | Sept. 14, 1896 | Galveston, TX | 507 | 22,461 | Frank P. Sargent |

| 19th Convention | Sept. 12, 1898 | Toronto | 538 | 27,039 | Frank P. Sargent |

| 20th Convention | Sept. 10, 1900 | Des Moines, IA | 569 | 36,084 | Frank P. Sargent |

| 21st Convention | Sept. 8, 1902 | Chattanooga, TN | 615 | 43,376 | John J. Hannahan |

| 22nd Convention | Sept. 12, 1904 | Buffalo | 660 | 54,434 | John J. Hannahan |

| 23rd Convention | Sept. 10, 1906 | Milwaukee | 699 | 58,849 | John J. Hannahan |

| 24th Convention | Sept. 14, 1908 | Columbus, OH | 760 | 66,408 | William S. Carter |

| 25th Convention | June 6, 1910 | St. Paul, MN | 759 | 65,315 | William S. Carter |

| 26th Convention | June 2, 1913 | Washington, D.C. | 826 | 85,292 | William S. Carter |

| 27th Convention | June 5, 1916 | Denver | 830 | 85,866 | William S. Carter |

| 28th Convention | June 9, 1919 | Denver | 880 | 116,990 | William S. Carter |

| 29th Convention | May 8, 1922 | Houston | 905 | 107,611 | David B. Robertson |

| 30th Convention | June 1, 1925 | Detroit | no data | 106,808 | David B. Robertson |

| 31st Convention | June 11, 1928 | San Francisco | no data | 104,167 | David B. Robertson |

| 32nd Convention | June 8, 1931 | Columbus, OH | no data | 98,187 | David B. Robertson |

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Paul Michel Taillon, Good, Reliable, White Men: Railroad Brotherhoods, 1877-1917. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2009; pg. 18.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Taillon, Good, Reliable, White Men, pg. 19.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Taillon, Good, Reliable, White Men, pg. 21.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Taillon, Good, Reliable, White Men, pg. 40.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Taillon, Good, Reliable, White Men, pg. 42.

- ↑ "UTU History". Retrieved June 20, 2011.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 D.B. Robertson, "Celebration of the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen and Enginemen: A Brief Narrative Telling the Story of the Founding of the Institution and a Brief Historical Outline of Its Growth and Development...," in Fiftieth Anniversary B of LF&E, 1873-1923. [no city]: Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen and Enginemen, 1923; pg. 7.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 F.P. Sargent, "A Short History of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen," in Carroll D. Wright (ed.), Fifth Annual Report of the Commissioner of Labor, 1889: Railroad Labor. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1890; pp. 40–41.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Taillon, Good, Reliable, White Men, pg. 44.

- ↑ Taillon, Good, Reliable, White Men, pg. 45.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Taillon, Good, Reliable, White Men, pg. 49.

- ↑ Taillon, Good, Respectable, White Men, pg. 47.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Taillon, Good, Reliable, White Men, pp. 50-51.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 14.6 14.7 Taillon, Good, Reliable, White Men, pg. 51.

- ↑ Nick Salvatore, Eugene V. Debs: Citizen and Socialist. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1982; pg. 26.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Constitution of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen. Terre Haute, IN: Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen, 1888; pp. 41-42. Cited in Taillon, Good, Reliable, White Men, pg. 57.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Taillon, Good, Reliable, White Men, pg. 57.

- ↑ James T. Sparrow, Warfare State: World War II Americans and the Age of Big Government. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011; p. 184.

- ↑ Mary Ann Clawson, Constructing Brotherhood: Class, Gender, and Fraternalism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989; pp. 129-130. Cited in Taillon, Good, Reliable, White Men, pg. 57.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 "Frank Pierce Sargent," in Gary M. Fink (ed.), Biographical Dictionary of American Labor. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1985; pg. 501.

- ↑ Taillon, Good, Reliable, White Men, pg. 54.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Mike McCormick, "Terre Haute was 'Convention City' in 1882," Terre Haute Tribune-Star, October 20, 2002.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 Robertson, "Celebration of the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen and Enginemen," pg. 19.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Finding Aid for Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen and Enginemen records, 1873-1975," Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives, Cornell University Library, Ithaca, New York.

Further reading

- Eric Arnesen, "'Like Banquo's Ghost, It Will Not Down': The Race Question and the American Railroad Brotherhoods, 1880-1920," American Historical Review, vol. 99, no. 5 (Dec. 1994), pp. 1601–1633. In JSTOR

- George R. Horton and H. Ellsworth Steele, "The Unity Issue among Railroad Engineers and Firemen," Industrial and Labor Relations Review, vol. 10, no. 1 (Oct. 1956), pp. 48–69. In JSTOR.

- Jon R. Huibregtse, American Railroad Labor and the Genesis of the New Deal, 1919-1935. University Press of Florida, 2010.

- Walter Licht, Working for the Railroad: The Organization of Work in the Nineteenth Century. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1983.

- Paul Michel Taillon, "'What We Want Is Good, Sober Men:' Masculinity, Respectability, and Temperance in the Railroad Brotherhoods, c. 1870-1910," Journal of Social History, vol. 36, no. 2 (Winter 2002), pp. 319–338. In JSTOR.

External links

- Finding Aid for Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen and Enginemen records, 1873-1975," Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives, Cornell University Library, Ithaca, New York.