Broom (plant)

| Broom | |

|---|---|

| |

| French broom, Genista monspessulana | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| (unranked): | Angiosperms |

| (unranked): | Eudicots |

| (unranked): | Rosids |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Fabaceae |

| Subfamily: | Faboideae |

| (unranked): | Core genistoids |

| Tribe: | Genisteae (Bronn) Dumort 1827[1] |

| Genera[2][3] | |

| |

| Synonyms[4] | |

| |

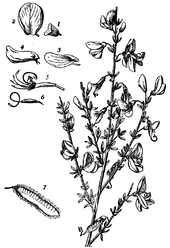

Brooms form a tribe, Genisteae, of evergreen, semi-evergreen, and deciduous shrubs in the subfamily Faboideae of the legume family Fabaceae, mainly in the three genera Chamaecytisus, Cytisus and Genista, but also in many other small genera (see box, right). These genera are all closely related and share similar characteristics of dense, slender green stems and very small leaves, which are adaptations to dry growing conditions. Most of the species have yellow flowers, but a few have white, orange, red, pink or purple flowers.

The term broom is also used more exclusively, for species of the genera Cytisus and Genista, or specifically for Cytisus scoparius (also known as Genista scoparia), native to Western Europe.

All members of Genisteae are natives of Europe, north Africa, the Canary Islands and southwest Asia (with the exceptions of Adenocarpus which extends into the mountains of tropical Africa, Anarthrophytum of the Andes, Aryrolobium which extends to South Africa and India, Dichilus, Melolobium and Polhillia of Southern Africa, Sellocharis of Brazil and Lupinus extending into eastern Africa and much of the Americas), with the greatest diversity in the Mediterranean. Many brooms (though not all) are fire-climax species, adapted to regular stand-replacing fires which kill the above-ground parts of the plants, but create conditions for regrowth from the roots and also for germination of stored seeds in the soil.

Description

The Genisteae arose 32.3 ± 2.9 million years ago (in the Oligocene).[5][6] The members of this tribe consistently form a monophyletic clade in molecular phylogenetic analyses.[2][7][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17] The tribe does not currently have a node-based definition, but several morphological synapomorphies have been identified:

… bilabiate calyces with a bifid upper lip and a trifid lower lip, … the lack of an aril, or the presence of an aril but on the short side of the seed, and stamen filaments fused in a closed tube with markedly dimorphic anthers … and presence of α-pyridone alkaloids.[2]

Most (and possibly all) genera in the tribe produce 5-O-methylgenistein.[18] Many genera also accumulate quinolizidine alkaloids, ammodendrine-type dipiperidine alkaloids, and macrocyclic pyrrolizidine alkaloids.[13][18]

Name

Old English bróm is from a common West Germanic *bráma- (Old High German brâmo, "bramble"), from a Germanic stem bræ̂m- of unknown origin, with an original sense of "thorny shrub" or similar. Use of the branches of these plants for sweeping gave rise to the term broom for sweeping tools in the 15th century, gradually replacing Old English besema (which survives as dialectal or archaic besom).[19]

Species of broom

The most widely familiar is common broom (Cytisus scoparius), a native of northwestern Europe, where it is found in sunny sites, usually on dry, sandy soils. Like most brooms, it has apparently leafless stems that in spring and summer are covered in profuse golden-yellow flowers. In late summer, its peapod-like seed capsules burst open, often with an audible pop, spreading seed from the parent plant. It makes a shrub about 1–3 metres (3 ft 3 in–9 ft 10 in) tall, rarely to 4 m (13 ft). It is also the hardiest broom, tolerating temperatures down to about −25 °C (−13 °F).

The largest species of broom is Mount Etna broom (Genista aetnensis), which can make a small tree to 10 metres (33 ft) tall; by contrast, some other species, e.g. dyer's broom Genista tinctoria, are low sub-shrubs, barely woody at all.

Broom is used as a food source by the larvae of some Lepidoptera species (see list of Lepidoptera that feed on brooms).

Cultivation

Brooms tolerate (and often thrive best in) poor soils and growing conditions. In cultivation they need little care, though they need good drainage and perform poorly on wet soils.

They are widely used as ornamental landscape plants and also for wasteland reclamation (e.g. mine tailings) and sand dune stabilising.

Tagasaste (Chamaecytisus proliferus), a Canary Islands native, is widely grown as sheep fodder.

Species of broom popular in horticulture are purple broom (Chamaecytisus purpureus; purple flowers), Atlas broom (or Moroccan broom) (Argyrocytisus battandieri, with silvery foliage), dwarf broom (Cytisus procumbens), Provence broom (Cytisus purgans) and Spanish broom (Spartium junceum).

Many of the most popular brooms in gardens are hybrids, notably Kew broom (Cytisus ×kewensis, hybrid between C. ardoinii and C. multiflorus) and Warminster broom (Cytisus ×praecox, hybrid between C. purgans and C. multiflorus).

Invasive species

In some areas of North America, common broom, introduced as an ornamental plant, has become naturalised and an invasive weed due to its aggressive seed dispersal; it has proved very difficult to eradicate. It is referred to locally as Scotch broom. Similarly, it is a major problem species in the cooler and wetter areas of southern Australia and New Zealand. Biological control for broom in New Zealand has been investigated since the mid-1980s. On the west coast of the United States, French broom (Genista monspessulana), Mediterranean broom (Genista linifolia) and Spanish broom (Spartium junceum) are also considered noxious invasives, as they are quickly crowding out native vegetation, and grow most prolifically in the least accessible areas.

Historical uses

The Plantagenet kings used common broom (known as planta genista in Latin) as an emblem and took their name from it. It was originally the emblem of Geoffrey of Anjou, father of Henry II of England. Wild broom is still common in dry habitats around Anjou, France.

Charles V and his son Charles VI of France used the pod of the broom plant (broom-cod, or cosse de geneste) as an emblem for livery collars and badges.[20]

Genista tinctoria (dyer's broom, also known as dyer's greenweed or dyer's greenwood), provides a useful yellow dye and was grown commercially for this purpose in parts of Britain into the early 19th century. Woollen cloth, mordanted with alum, was dyed yellow with dyer's greenweed, then dipped into a vat of blue dye (woad or, later, indigo) to produce the once-famous "Kendal Green" (largely superseded by the brighter "Saxon Green" in the 1770s). Kendal green is a local common name for the plant.

The flower buds and flowers of Cytisus scoparius have been used as a salad ingredient, raw or pickled, and were a popular ingredient for salmagundi or "grand sallet" during the 17th and 18th century. There are now concerns about the toxicity of broom, with potential effects on the heart and problems during pregnancy.

Folklore and myth

In Welsh mythology, Blodeuwedd is the name of a woman made from the flowers of broom, meadowsweet and the oak by Math fab Mathonwy and Gwydion to be the wife of Lleu Llaw Gyffes. Her story is part of the Fourth Branch of the Mabinogi, the tale of Math son of Mathonwy.

A traditional rhyme from Sussex says: "Sweep the house with blossed broom in May/sweep the head of the household away." Despite this, it was also common to include a decorated bundle of broom at weddings. Ashes of broom were used to treat dropsy, while its strong smell was said to be able to tame wild horses and dogs.

See also

Notes

References

- ↑ Wojciechowski, MF (2013). "Towards a new classification of Leguminosae: Naming clades using non-Linnaean phylogenetic nomenclature". S Afr J Bot 89: 85–93. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2013.06.017.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Cardoso, D.; Pennington, RT; de Queiroz, LP; Boatwright, JS; Van Wyk, B-E; Wojciechowski, MF; Lavin, M. (2013). "Reconstructing the deep-branching relationships of the papilionoid legumes". S Afr J Bot 89: 58–75. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2013.05.001.

- ↑ USDA; ARS; National Genetic Resources Program (2003). "GRIN genus records of Genisteae". Germplasm Resources Information Network—(GRIN) [Online Database]. Beltsville, Maryland: National Germplasm Resources Laboratory. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- ↑ Polhill, RM; van Wyk, B-E. (2013). "Kew entry for Genisteae". www.kew.org. London, England: Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- ↑ Boatwright, JS; Savolainen, V; Van Wyk, B-E; Schutte-Vlok, AL; Forest, F; Van der Bank, M. (2008). "Systematic position of the anomalous genus Cadia and the phylogeny of the tribe Podalyrieae (Fabaceae)". Syst Bot 33 (1): 133–147. doi:10.1600/036364408783887500.

- ↑ Lavin, M; Herendeen, PS; Wojciechowski, MF (2005). "Evolutionary rates analysis of Leguminosae implicates a rapid diversification of lineages during the tertiary". Syst Biol 54 (4): 575–94. doi:10.1080/10635150590947131. PMID 16085576.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 van Wyk B-E, Schutte AL. (1995). "Phylogenetic relationships in the tribes Podalyrieae, Liparieae and Crotalarieae". In Crisp M, Doyle JJ. Advances in Legume Systematics, Part 7: Phylogeny. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. pp. 283–308. ISBN 0947643796.

- ↑ Boatwright JS, le Roux MM, Wink M, Morozova T, van Wyk B-E. (2008). "Phylogenetic relationships of tribe Crotalarieae (Fabaceae) inferred from DNA sequences and morphology". Syst Bot 33 (4): 752–761. doi:10.1600/036364408786500271. JSTOR 40211942.

- ↑ Cardoso D, de Queiroz LP, Pennington RT, de Lima HC, Fonty É, Wojciechowski MF, Lavin M. (2012). "Revisiting the phylogeny of papilionoid legumes: new insights from comprehensively sampled early-branching lineages". Am J Bot 99 (12): 1991–2013. doi:10.3732/ajb.1200380.

- ↑ Käss E, Wink M. (1996). "Molecular evolution of the Leguminosae: Phylogeny of the three subfamilies based on rbcL-sequences". Biochem Syst Ecol 24 (5): 365–378. doi:10.1016/0305-1978(96)00032-4.

- ↑ Käss E, Wink M. (1997). "Phylogenetic Relationships in the Papilionoideae (Family Leguminosae) Based on Nucleotide Sequences of cpDNA (rbcL) and ncDNA (ITS 1 and 2)". Mol Phylogenet Evol 8 (1): 65–88. doi:10.1006/mpev.1997.0410. PMID 9242596.

- ↑ Doyle JJ, Doyle JL, Ballenger JA, Dickson EE, Kajita T, Ohashi H. (1997). "A phylogeny of the chloroplast gene rbcL in the Leguminosae: taxonomic correlations and insights into the evolution of nodulation". Am J Bot 84 (4): 541–554. doi:10.2307/2446030. PMID 21708606.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Wink M, Mohamed GIA. (2003). "Evolution of chemical defense traits in the Leguminosae: mapping of distribution patterns of secondary metabolites on a molecular phylogeny inferred from nucleotide sequences of the rbcL gene". Biochem Syst Ecol 31 (8): 897–917. doi:10.1016/S0305-1978(03)00085-1.

- ↑ Wojciechowski MF, Lavin M, Sanderson MJ. (2004). "A phylogeny of legumes (Leguminosae) based on analysis of the plastid matK gene resolves many well-supported subclades within the family". Am J Bot 91 (11): 1846–1862. doi:10.3732/ajb.91.11.1846. PMID 21652332.

- ↑ Crisp MD, Gilmore S, Van Wyk B-E. (2000). "Molecular phylogeny of the genistoid tribes of papilionoid legumes". In Herendeen PS, Bruneau A. Advances in Legume Systematics, Part 9. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. pp. 249–276. ISBN 184246017X.

- ↑ Kajita T, Ohashi H, Tateishi Y, Bailey CD, Doyle JJ. (2001). "rbcL and legume phylogeny, with particular reference to Phaseoleae, Millettieae and allies". Syst Bot 26 (3): 515–536. doi:10.1043/0363-6445-26.3.515. JSTOR 3093979.

- ↑ LPWG [Legume Phylogeny Working Group] (2013). "Legume phylogeny and classification in the 21st century: progress, prospects and lessons for other species-rich clades". Taxon 62 (2): 217–248. doi:10.12705/622.8.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Van Wyk B-E. (2003). "The value of chemosystematics in clarifying relationships in the Genistoid tribes of papilionoid legumes". Biochem Syst Ecol 31 (8): 875–884. doi:10.1016/S0305-1978(03)00083-8.

- ↑ Shorter Oxford English dictionary, 6th ed. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. 2007. p. 3804. ISBN 0199206872.

- ↑ Nichols JG. (1842). "III. Observations on the Heraldic Devices discovered on the Effigies of Richard the Second and his Queen in Westminster Abbey, and upon the Mode in which those Ornaments were executed; including some Remarks on the surname Plantagenet, and on the Ostrich Feathers of the Prince of Wales". In Society of Antiquaries of London. Archaeologia: or, Miscellaneous Tracts Relating to Antiquity XXIX. J. B. Nichols and Son, London. p. 45.

Further reading

- Mabey, Richard, Flora Britannica, Sinclair-Stevenson, London, 1996, ISBN 1-85619-377-2

- Royal Horticultural Society's plant database