Broadmoor Hospital

| Broadmoor Hospital | |

|---|---|

| West London Mental Health NHS Trust | |

Broadmoor in 2006 | |

| |

| Geography | |

| Location | Crowthorne, Berkshire, England, United Kingdom |

| Coordinates | 51°22′09″N 0°46′43″W / 51.369128°N 0.778720°WCoordinates: 51°22′09″N 0°46′43″W / 51.369128°N 0.778720°W |

| Organisation | |

| Care system | Public NHS |

| Hospital type | Psychiatric |

| Services | |

| Emergency department | No Accident & Emergency |

| Beds | 284 |

| History | |

| Founded | 1863 |

| Links | |

| Website | Official website |

| Lists | Hospitals in England |

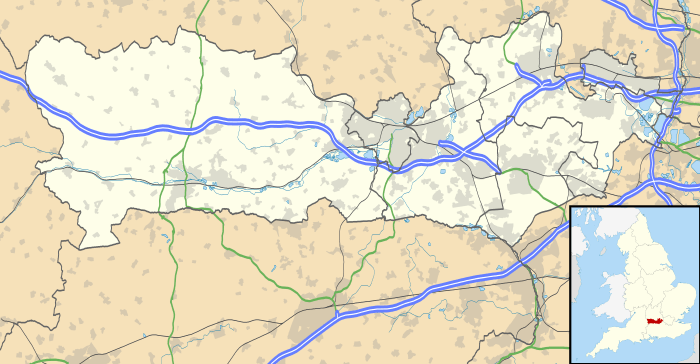

Broadmoor Hospital is a high-security psychiatric hospital at Crowthorne in the Borough of Bracknell Forest in Berkshire, England. It is the best known of the three high-security psychiatric hospitals in England, the other two being Ashworth and Rampton. Scotland has a similar institution at Carstairs, officially known as the State Hospital but often called Carstairs Hospital, which serves Scotland and Northern Ireland.

The Broadmoor complex houses about 210 patients, all of whom are men since the female service closed with most of the women moving to a new service in Southall in September 2007, a few moving to the national high secure service for women at Rampton and a few elsewhere. At any one time there are also approximately 36 patients on trial leave at other units. Most of the patients there suffer from severe mental illness; many also have personality disorders. Most have either been convicted of serious crimes, or been found unfit to plead in a trial for such crimes. The average stay for the total population is about six years, but this figure is skewed by some patients who have stayed for over 30 years; most patients stay for considerably less than six years.

The catchment area for the hospital underwent some rationalisation of the London area in the early 21st century, and now serves all of the NHS Regions: London, Eastern, South East and South West.

History

The hospital was first known as the Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum. It was built to a design by Sir Joshua Jebb, an Officer of the Corps of Royal Engineers, and covered 53 acres (210,000 square metres) within its secure perimeter. The first patient was a female admitted for infanticide, on 27 May 1863. Notes described her as being 'feeble minded'; it has been suggested by an analysis of notes that she was most likely also suffering from congenital syphilis. The first male patients arrived on 27 February 1864. The original building plan of five blocks for men and one for women was completed in 1868. A further male block was built in 1902.

Due to overcrowding at Broadmoor, a branch asylum was constructed at Rampton Secure Hospital and opened in 1912. Rampton was closed as a branch asylum at the end of 1919 and reopened as an institution for mental defectives rather than lunatics. During World War I Broadmoor's block 1 was also used as a prisoner-of-war camp, called Crowthorne War Hospital, for mentally ill German soldiers.[1]

After the escape and the murder of a local child in 1952 by John Straffen, the hospital set up an alarm system, which is activated to alert people in the vicinity, including those in the surrounding towns of Sandhurst, Wokingham, Bracknell and Bagshot, when any potentially dangerous patient escapes. It is based on World War II air-raid sirens, and a two-tone alarm sounds across the whole area in the event of an escape. It is tested every Monday morning at 10 am for two minutes, after which a single tone 'all-clear' is sounded for a further two minutes. All schools in the area must keep procedures designed to ensure that in the event of a Broadmoor escape no child is ever out of the direct supervision of a member of staff. Sirens are located at Sandhurst School, Wellington College, Bracknell Forest council depot and other sites.[2][3]

Following the Peter Fallon QC inquiry into Ashworth Special Hospital which reported in 1999, and found serious concerns about security and abuses resulting from poor management, it was decided to review the security at all three of the special hospitals in England. Until this time each was responsible for maintaining its own security policies.[4][5] This review was made the personal responsibility of Sir Alan Langlands, who at the time was Chief Executive of the National Health Service (England). The report that came out of the review initiated a new partnership whereby the Department of Health sets out a policy of safety, and security directions, that all three special hospitals must adhere to.[5]

This has resulted in upgraded physical security at Broadmoor from approximately category 'C' to category 'B' prison standards. Higher levels of security than this are then placed around certain buildings. New standards have also been formulated to increase procedural security and safety for the staff and other patients; these include procedures and equipment for reducing the amount of contraband smuggled into the hospital.

In 2003 the Victorian buildings at Broadmoor were declared 'unfit for purpose' by the Commission For Healthcare Improvement..

As well as providing patient care Broadmoor is a centre for training and research.

Therapies

Broadmoor uses both psychiatric medication and psychotherapy.

One of the therapies available is the arts, and patients are encouraged to participate in the Koestler Awards Scheme.[6]

One of the longest-detained patients at Broadmoor is Albert Haines, who set a legal precedent in 2011 when his mental health tribunal hearing was allowed to be fully public despite the protestations of Broadmoor. Haines, a survivor of childhood abuse in care homes, contested his diagnoses and argued that he has never been given the type of non-directive counselling he has always sought. He remains at Broadmoor though the tribunal panel urged the clinicians to work more collaboratively and clearly towards his psychiatric rehabilitation. Haines was shown in an ITV documentary filmed inside Broadmoor in 2014.

Misconceptions

| Psychology |

|---|

| Basic types |

| Applied psychology |

| Lists |

|

Because of its high walls and other visible security features, and the inaccurate news reporting it has received in the past, it is occasionally presumed by some members of the general public that Broadmoor Hospital is a prison.[7] Many of its patients are referred to it by the criminal justice system, and its original design brief incorporated an essence of addressing criminality in addition to mental illness; however, the layout inside and the daily routine are designed to assist the therapy practiced there rather than to meet the criteria necessary for it to be run along the lines of a prison in its daily functions.[8] Nearly all staff are members of the Prison Officers Association,[9] as opposed to the health service unions like UNISON.

Jimmy Noak, Broadmoor's director of nursing in 2011, in response to concerns about the amount of resources going into the treatment of those in the facility given the harm some of them had caused to victims or their families, commented, "It's not fair, but what is the alternative? If these people committed crimes because they were suffering from an acute mental illness then they should be in hospital."[2]

Governance

Historically

From its opening, until 1948, Broadmoor was managed by a Council of Supervision, appointed by and reporting to the Secretary of State for the Home Department (Home Secretary). Thereafter, the Criminal Justice Act of 1948 transferred ownership of the hospital to the Department of Health (and the new NHS) and oversight to the Board of Control for Lunacy and Mental Deficiency established under the Mental Deficiency Act 1913. It also renamed the hospital Broadmoor Institution. The hospital remained under direct control of the Department of Health - a situation which reportedly "combined notional central control with actual neglect"[10] until the establishment of the Special Hospitals Service Authority in 1989, with Charles Kaye as initial Chief Executive.[9]

Alan Franey ran the hospital from 1989 to 1997, having been recommended for the post by his friend Jimmy Savile. His leadership was undermined by persistent rumours of sexual impropriety on the hospital grounds and he allegedly ignored at least three sexual assaults he was informed about.

In 1996 the SHSA itself was abolished, being replaced by individual special health authorities in each of the High Secure Hospitals. The Broadmoor Hospital Authority was itself dissolved on 31 March 2001.[11]

Currently

On 1 April 2001 West London Mental Health (NHS) Trust took over the responsibility for the hospital. Thie Trust reports to the NHS Executive through the London Strategic Health Authority. Leeanne McGee is Broadmoor’s executive director.

The WLMHT Broadmoor management have become embroiled in some controversy over failed CCTV camera software and a botched tendering process for the new contract to replace it, and an anti-fraud investigation over millions of overspend in its estates and facilities department.[12]

A new head of security (private contracted company) was appointed in March 2013 - John Hourihan, formerly of Scotland Yard for 30 years and bodyguard to members of the British Royal Family.[13]

Meanwhile the Trust allowed ITV to film a two-part documentary within Broadmoor, the first time TV cameras had been allowed inside to broadcast.[14]

Buildings

Much of Broadmoor remains Victorian-era buildings, fronted by a Grade 1 listed gatehouse with a clocktower.

A new unit called the Paddock Centre was opened on 12 December 2005 to contain and treat patients categorised as having a "dangerous severe personality disorder" (DSPD).[15] This was a new and much debated category invented on behalf of the UK government, based on an individual being considred a 'Grave and Immediate Danger' to the general public, and meeting some combination of criteria for personality disorders and/or high scores on the Hare Psychopathy Check list – Revised. The Paddock Centre was designed to eventually house 72 patients, but never opened more than four of its six 12-bedded wards. The Dept of Health and Ministry of Justice National Personality Disorder Strategy published in October 2011 concluded that the resources invested in the DSPD programme should instead be used in prison based treatment programmes and the DSPD service at Broadmoor was required to close by 31 March 2012. The patients were transferred either back to prison, on to medium secure units to continue treatment, on to the residual national DSPD service at the Peaks Unit in Rampton, or to elsewhere in Broadmoor in the Personality Disorder directorate. The Paddock now, in 2013, provides general admission wards and high dependency wards for both the mental illness and personality disorder directorates, and all 72 beds are in use.

Following reports that the old buildings are unfit for purpose, whether therapy or safety of patients or staff, planning permission was granted in 2012 for a £298 million redevelopment, involving a new unit comprising 10 wards to adjoin the existing 6 wards of the modern Paddock Unit, resulting in total bed numbers of 234. Building company Kier reported in 2013 a sum of £115m for the new unit of 162 beds, ready to accept patients by the start of 2017, and £43m for a separate new medium secure unit for men nearby.

Abuse by staff

From 1968, after telephoning Broadmoor's entertainments officer and within weeks gaining the trust of the chief executive Pat McGrath who thought it would be good publicity, the TV presenter and disc jockey Jimmy Savile undertook voluntary work at the hospital, raised some funds for it, and was allocated his own room there.[16][17]

In 1987, a minister in the Department of Health and Social Security, Jean Barker, Baroness Trumpington, appointed Savile to the management board in charge of Broadmoor. He was now being referred to as "Dr Savile" by both the Department and Broadmoor, as well as in the House of Lords by Alexander Scrymgeour, 12th Earl of Dundee, despite Savile having no medical or research qualifications or training whatsoever, and only an 'honorary degree' (not a real one) in law from Leeds University which was not mentioned.

In August 1988, following recommendation by the senior civil servant in charge of mental health at the DHSS, Cliff Graham, Savile was appointed by the Department's health minister Edwina Currie to chair an interim task force overseeing the management of the hospital following the suspension of the board. Currie privately supported Savile's attempts to "blackmail" the Prison Officers Association and publically declared her "full confidence" in him.[18][19][20]

After the ITV1 documentary Exposure: The Other Side of Jimmy Savile was broadcast in October 2012, allegations of sexual abuse by Savile at the hospital and elsewhere were made by former patients and staff.[16][21][22] The civil servant who proposed Savile's appointment to the task force at Broadmoor, Brian McGinnis, who ran the mental health division of the Department of Health and Social Services in 1987, has since been investigated by police and prevented from working with children.[23] The Department of Health announced an investigation led by former barrister Kate Lampard into Savile's activities at Broadmoor and other hospitals and facilities in England,[24] with Bill Kirkup leading the Broadmoor aspects. The report, published in 2014, found that Savile had use of a personal set of keys to Broadmoor from 1968 to 2004 (a right not formally revoked until 2009), with full unsupervised access to some wards. 11 allegations of sexual abuse were brought to the attention of the investigators, thought to be a substantial under-estimate of the true figures due to how the psychiatric patients in particular were put off from coming forward or being believed at the time. In five cases the identity of the alleged victim was no longer known and they could not be traced, but investigators were able to examine the other six and concluded they had all indeed been abused by Savile - repeatedly in the case of two patients. The investigation also concluded that "the institutional culture in Broadmoor was previously inappropriately tolerant of staff–patient sexual relationships", and that when there were female patients they were required to undress and bathe infront of staff, including Savile.

Journalists invading the privacy of patients or reporting false information about them have been the subject of dozens of complaints from Broadmoor. Healthcare assistant Robert Neave took payments from The Sun for several years to provide them with information, including copies of psychiatric reports, which has subsequently been investigated by Operation Elveden.

Notable patients - past and present

|

|

See also

- Ashworth high-security psychiatric hospital

- Forensic psychiatry

- Rampton high-security psychiatric hospital

- West London Mental Health NHS Trust, which holds the commission from the Secretary of State for the Home Department to run this hospital.

References

- ↑ Berkshire Record Office catalogue of Broadmoor Hospital records, introduction

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 BBC - h2g2 - The Broadmoor Siren

- ↑ The Broadmoor siren. WLMHT. Accessed 1 July 2012

- ↑ Fallon, Peter; Bluglass, Robert; Edwards, Brian; Daniels, Granville (January 1999) Report of the Committee of Inquiry into the Personality Disorder Unit, Ashworth Special Hospital. published by the Stationery Office. Accessed 12 November 2007

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Langlands, Alan (22 May 2000). Report of the review of security at the high security hospitals. Department of Health. Accessed 12 November 2007

- ↑ The fine art of starting over The Guardian, 2006

- ↑ Press Complaints Commission (9 Jan 2009) Broadmoor Hospital Accessed 1 March 2009

- ↑ Lemlij, Maia (November 2005) Broadmoor Hospital: Prison-like hospital or hospital-like prison? A study of a high security mental hospitals within the context of generic function. pages 155, 156. Space Syntax Laboratory, UK. Accessed 21 February 2009

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Charles Kaye and Alan Franey (1998). Managing High Security Psychiatric Care. Jessica Kingsley. pp. 31,40. ISBN 9781853025815. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- ↑ Ashworth Special Hospital: Report of the Committee of Inquiry

- ↑ National Archives, Office of Public Sector Information. Broadmoor Hospital Authority (Abolition) Order 2001. ISBN 0-11-029108-5. Accessed 14 June 2007

- ↑ Broadmoor facing £3m bill to fix security flaws at psychiatric hospital February 2015, The Independent

- ↑ Prince William, Kate Middleton 'upset' after bodyguard quits March 2013, Digital Spy

- ↑ Broadmoor: ITV doc offers first ever look inside highest-security psychiatric hospital Nov 2014, The Independent

- ↑ "Dangerous & Severe Personality Disorder Programme". National Personality Disorder Organisation (UK). Archived from the original on 24 February 2007. Retrieved 15 May 2007.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Daily Telegraph, "Broadmoor staff said Jimmy Savile was a 'psychopath' with a 'liking for children'", 1 November 2012. Accessed 1 November 2012

- ↑ Adam Sweeting (29 October 2011). ""Sir Jimmy Savile obituary" at guardian.co.uk". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 1 October 2012.

- ↑ Jimmy Savile: detailed investigation reveals reign of abuse across NHS June 2014 The Guardian

- ↑ The Earl of Dundee (7 November 1988). "Mentally Ill Offenders: Treatment". Hansard (Lords). HL Deb 7 November 1988 vol 501 c525. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- ↑ "Edwina Currie - 'nothing to hide' on Savile". BBC News. 21 October 2012. Retrieved 21 October 2012.

- ↑ Evans, Martin (11 October 2012). "Sir Jimmy Savile: fourth British TV personality accused in sex allegations". The Telegraph (London). Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- ↑ Addley, Esther; O'Carroll, Lisa (12 October 2012). "Jimmy Savile scandal: government could face civil claims". The Guardian (London). Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- ↑ Donnelly, Laura (27 October 2012). "Jimmy Savile's relatives speak of their turmoil". The Telegraph (London). Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- ↑ "Jimmy Savile scandal: Kate Lampard to lead NHS investigation". BBC News (BBC). 17 October 2012. Retrieved 17 October 2012.

- ↑ Facts related in non-fictional book Savage Grace by Natalie Robins and Steven M.L. Aronson [1985, ISBN 978-0-688-04373-5], and more recently in the Tom Kalin's film Savage Grace (2007)

- ↑ Daily Times of Pakistan, Terrorists planning chemical hit on European targets, 19 December 2002

- ↑ BBC News | England | Devon | Failed bomber's recruiters hunted

- ↑ Daily Times of Pakistan, Euro judges rule that terror suspect wanted in America CAN'T be deported from Britain to the U.S. because it would be bad for his mental health

Further reading

- Dell, Susanne; Graham Robertson (1988). Sentenced to hospital: offenders in Broadmoor. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-712156-X. OCLC 17546264. Dewey Class 365/.942294 19. Sum: authors describe the treatment of some Broadmoor patients and together with their psychiatric and criminal histories.

- Partridge, Ralph (1953). Broadmoor: A History of Criminal Lunacy and its Problems. London: Chato and Windus. OCLC 14663968.

- The Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health (2006).First steps to work – a study at Broadmoor Hospital (119KB). Accessed 2007-06-15

- Stevens, Mark (2011). Broadmoor Revealed: Victorian Crime and the Lunatic Asylum. Broadmoor Revealed. Accessed 2011-07-15

External links

- Official website

- Berkshire Record Office's Broadmoor History pages Accessed 2011-04-18

- Fallon, Peter; Bluglass, Robert; Edwards, Brian; Daniels, Granville (January 1999) Report of the Committee of Inquiry into the Personality Disorder Unit, Ashworth Special Hospital. published by The Stationery Office. Accessed 2007-11-12

- Paddock centre. DSPD service. West London Mental Health Trust. Accessed 2007-05-15

- Home Office. National offenders management service. Dangerous People with Severe Personality Disorder Programme. Accessed 2007-06-07

- All in the mind (Wednesday 3 March 2004, 5.00 pm). BBC – Live chat:The rehabilitation of the mentally ill in Broadmoor and elsewhere. Accessed 2007-05-19

- BBC News background on Broadmoor Hospital

- Landscapes & Gardens (2002) Architectural listing for Broadmoor Hospital. University of York. Accessed 2007-05-19

- BBC News story on scandals and controversy regarding Broadmoor and other secure hospitals

- "NHS in England". Broadmoor Hospital Site Summary Information. Retrieved 26 March 2006.

- Together-UK Independent Patients' Advocacy Service, for Broadmoor Hospital. Accessed 2007-06-15

- Fallon, Peter; Bluglass, Robert; Edwards, Brian; Daniels, Granville (January 1999) - overview of the History of the Hospitals in the context of the Ashworth Inquiry Accessed June 2008